Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Long Way Home"

First published in Great Britain in 1975 by Macmillan Education Ltd

This edition published 2012 by Egmont UK Limited

The Yellow Building, 1 Nicholas Road, London W11 4AN

Text Copyright © 1975 Michael Morpurgo

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978 1 4052 2669 1

Ebook ISBN 978 1 7803 1736 6

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at the time of going to print. However, Egmont is not responsible for content hosted by third parties. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are supervised when using the internet.

For Clare

CONTENTS

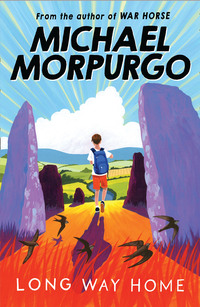

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

Back series promotional page

CHAPTER 1

THE CAR PURRED COMFORTABLY AND GEORGE was bored with looking out of the window. He glanced down as Mrs Thomas changed gear, and he noticed that she had rather fat legs. She wore thick stockings that wrinkled at the ankles. He didn’t like fat legs. Mrs Thomas had been his social worker for as long as he could remember, but he’d never noticed her legs before. She half turned her head, and George looked away quickly, hoping she hadn’t seen him staring. He felt his face flush, but it went away quickly.

‘They’re really very nice people, George,’ she said. ‘I’ve known them for years now. I know you’ll like Mr and Mrs Dyer. They work on the farm all by themselves, you know. Must be very hard work, I should think. Could do with some help, I expect. You’ve never lived on a farm before, have you, George?’

‘No,’ said George.

‘There’ll be a lot for you to learn. They’ll keep you busy, I shouldn’t wonder.’

‘I told you, I don’t want to go.’

‘But George, there’s hardly anyone left at the Home – no one your age, anyway. They’re all on holiday.’ She changed gear badly again and the Mini juddered along painfully at twenty miles an hour in top gear.

‘I don’t care,’ George muttered.

‘And anyway it’s good for you to get away sometimes – good for everyone. We all need a change, don’t we?’

‘When can I come back?’

‘Try not to think of that, George. You’ll enjoy it, really you will.’

‘When?’ George insisted, turning to look at her.

‘Well, term starts again early in September – you’ll have to go back for that; but they’re nice people, George, it’s a lovely place and I know they’re looking forward to having you.’

Mrs Thomas had known George all his life – ever since he first came to live at the Home when he was three years old, and this was a conversation she had been through with him every time she’d taken him to new foster parents. She knew her credibility must be wearing very thin. Every time they were going to be ‘nice people’ in a ‘good home’. Every time he said he didn’t want to go. And every time he was back in the Home within a year, sometimes within a month. He’d run away twice – back to the Home. In all there had been six sets of foster parents, but for one reason or another none of them had worked out: either they hadn’t liked him because he was too quiet and sullen, or more often he just hadn’t taken to them. It all made anything she said sound hollow and weak, but she had to say something.

‘September? But that’s over four weeks away.’

Mrs Thomas tried to ignore the despair in his voice and concentrated on the road; there was nothing else she could say about it, nothing that would help.

‘Would you like the radio on?’ she asked. But George said nothing; he was looking out of the window again. She leaned forward and switched it on anyway – anything was better than this silence.

‘Do I have to, Mrs Thomas?’ George was pleading now. ‘Do I have to go?’

‘Let’s give it a try, George,’ she said. ‘It’s only for the holidays after all, and you never know, you may have a wonderful time. Just give them time to get to know you – you’ll be all right.’ She knew George well enough by now to know that he’d lapse into a long silence until they arrived. She was bad at small talk and he had never responded to it, so she reached forward again and turned up the radio, filling the car with the raucous sound of a Radio One jingle and obliterating the silence that had fallen between them.

Tom pushed away his cereal bowl and began to butter his piece of toast. ‘What time’s he coming?’ he said, pushing the butter angrily into the holes in the toast.

‘I don’t know, dear. Some time mid-morning, I think,’ said his mother.

‘Every year we do it, Mum. Do we have to do it every year? There must be other people . . .’

‘We’ve been through all this before, Tom,’ said his mother, leaving the stove with a plate of sausages.

‘You said you wouldn’t make a fuss this time – we agreed.’ A door banged upstairs. ‘Please, Tom. Dad’s coming down – don’t go on about it.’

The door was pushed open, and Tom’s father came into the kitchen in his dressing-gown and slippers. ‘Those calves, they’ll have to be moved,’ he said, stroking his chin. ‘I hardly shut my eyes last night with all that mooing.’ He pulled the newspaper out of the back door letter-box, shook it open and sat down.

‘And I suppose you’ll want me to move them,’ said Tom, looking at the picture on the back page of the newspaper and thinking that the Prime Minister looked about the same age as his father. The Prime Minister’s face folded up in front of him as his father lowered the paper.

‘It’s Saturday, isn’t it?’ Tom knew what was coming. ‘I give you five pounds for working weekends on the farm in the summer holidays, five pounds! I run this farm by myself, we’ve no other help . . .’

‘Dad, I didn’t mean it like that . . .’ But it was no use.

‘And it’s not as if you even put in a full two days, and every time I ask you to do anything extra, you gripe about it. Your mother and me, we . . .’

‘Dad, I was just asking, that’s all, just asking if you wanted me to move those calves.’ Tom felt his voice rising in anger and tried to control it. ‘Now, do you want me to move them or not?’

‘That’s not what it sounded like to me,’ his father said, retreating a bit.

‘Oh, do stop it, you two. Storme’s awake, you know – she’ll hear you,’ said Tom’s mother and she scuffled across the kitchen floor towards them with the teapot in one hand and a jug of milk in the other. ‘Pour yourselves a cup of tea and do eat your sausages, Tom; they’ll be cold.’

‘She’s heard us before, Mum,’ said Tom. ‘She’s used to it.’

Tom’s sister, Storme, thundered down the stairs, the kitchen door banged open and she came hopping in, pulling on a shoe that had come loose.

‘It’s today, isn’t it?’ she said, scraping back her chair.

‘What is dear?’ said her mother.

‘That boy, that foster boy,’ she said. ‘He’s coming today, isn’t he?’

‘Storme, I told you,’ her mother said, sitting down for the first time that morning. ‘I told you, you’re not to call him that. You call him by his name, and his name’s George.’

‘It’s not her fault, Mum,’ Tom said, stabbing at the sausage with his fork and looking for the softest place to make an incision. ‘Every summer I can remember we’ve had a foster child living with us, and they’ve all had different names.’

‘Well this one’s called George, and don’t you forget it,’ the newspaper said. The Prime Minister had his legs back again.

‘Why do we do it, Mum?’ Storme asked, scraping the last drop of milk from the bottom of her cereal bowl.

‘Do what, dear?’

‘Have all these foster children.’

‘I don’t really know, dear. I suppose it was your Auntie Helen who started it when she was a probation officer in Exeter – years ago now, before we had you. She suggested we might have a foster child out here for a few weeks in the summer – Anne was the first one, about your age now – and after that the habit just stuck. They wouldn’t get a holiday otherwise, you know.’

‘You don’t know how lucky you are,’ said her father.

‘Lucky!’ said Tom. ‘What about last year then? That girl Jenny, she wouldn’t talk to anyone but Mum, you only had to look at her and she’d cry and she never stopped fighting with Storme.’

‘You’re a fine one to talk,’ his mother said.

‘Oh, come on, Mum, she was a bloody nuisance – you know she was.’

‘Tom!’

‘Well, she was,’ Tom said. ‘And what about the time she left the gate of the water-meadow open, “by mistake” she said, and let all the sheep out?’ Tom’s mother tried to pour herself another cup of tea. Tom watched as the tea trickled away to tea-leaves.

‘She was only young, Tom,’ she said quietly, ‘and a city girl at that.’ She filled the teapot, pulling her head away as the steam rose into her face. ‘And if I remember rightly,’ she went on, ‘it was you that left the tractor lights on all night last Saturday, wasn’t it?’ Tom knew she was right, but that just made him feel more resentful.

‘Anyway,’ he said, ‘Dad said we wouldn’t do it again after her.’

‘I said nothing of the kind,’ his father said, folding the newspaper. ‘I said we should choose more carefully next time, that’s all – someone older, more adaptable.’

‘And George is twelve, Tom,’ said his mother, ‘nearly your age. Mrs Thomas says he’s a nice boy – shy and quiet, but nice. He just hasn’t managed to settle anywhere.’ She was scraping off the jam Tom had left on the butter. That was something else Tom and his father were always quarrelling about: dirtying the butter. She hated it when they argued.

‘What’s “adaptable”?’ Storme asked, but no one answered her. She was used to that, so she tried again, pulling at her mother’s elbow. ‘Mum, Mum, what’s “adaptable” mean?’ But her mother wasn’t listening to her, and Storme wasn’t that interested anyway, so she gave up and went back to her sausage.

‘I wonder why though?’ Tom asked.

‘Why what?’ his mother said.

‘Why he didn’t settle anywhere else?’

‘Well, I don’t know,’ Tom’s mother said. ‘Mrs Thomas didn’t say.’

‘She wouldn’t, would she?’ Tom said.

‘Now what exactly do you mean by that?’ There was an edge to his father’s voice.

‘Well, if there was something wrong about him, she wouldn’t tell you, would she? You wouldn’t have him, would you?’ Tom looked deliberately at his mother. He was trying to avoid another confrontation with his father. ‘Anyway,’ he went on, ‘she always sends us the worst cases, you know that. You’re the only ones that’ll take them.’

‘That’s enough, Tom,’ said his mother, but Tom ignored the plea in her voice. He didn’t want this George to stay in the house. There had been only one foster child he’d got on with, and he’d been taken away after two weeks because they’d found a permanent home for him somewhere else. The rest of them had just been a nuisance. George might be more his own age than most of them, but somehow that made it worse, not better.

‘I can tell you one thing,’ Tom said, pushing his sausage plate away. ‘I’m not going to look after him all the time, I can tell you that.’

‘Please, Tom!’ His mother was leaning towards him begging him to stop, but Tom couldn’t respond to her – it had gone too far already.

‘I’ve got better things to do,’ he said, and as he said it, he knew it sounded a challenge to his father.

‘Like working on the farm, I suppose. Moving calves, perhaps?’ His father was speaking quietly. Tom recognised the warning sign, but ignored it. It was his holiday they were interfering with and there was only one summer holiday each year.

‘I don’t want him here. I’ve got my own friends, haven’t I? He’ll just be in the way, and what’s more you never even asked me about it. It was all arranged between you and Dad and that Mrs Thomas. You’re not going to look after him, I am – and no one bothered to ask me, did they?’

‘That’s not fair, Tom.’ His mother sounded hurt, and Tom looked at her. She looked away and began piling up the plates, avoiding Tom with her eyes. ‘You know very well I asked you about having another one this summer, and you agreed – well, you said you didn’t mind anyway. Anyhow when Mrs Thomas rang up and told me about George, I had to say yes.’

He hadn’t meant to upset his mother and he didn’t want to go on, but he couldn’t bring himself to finish without a final gesture of protest. He scraped back his chair and stood up. And then his father took the wind out of his sails.

‘You’ve said enough.’ His father was glaring up at him. ‘You’re always saying that we treat you like a child. Just listen to yourself. You carry on like a six-year-old.’

‘When’s he coming?’ Storme asked, apparently oblivious of the anger on the other side of the table. It was a fortunately-timed question. Tom and his father were steamed up and ready for battle. Her mother took the opportunity with both hands. ‘Mid-morning,’ she said hastily. ‘She said they’d be here some time around elevenish. It would be nice if all of us could be here to meet him – don’t you think, Tom?’

Tom knew she hated his arguments with his father, but it had been better this holiday so far – hardly one serious quarrel until now. He’d managed to control his temper and even his father seemed less inclined to provoke a row. He looked down at his mother and saw in her face that weary, beseeching smile he’d seen so often when she was trying to bring a truce between them.

‘I’ll be there, Mum,’ he said, pushing his chair in.

‘You’ll be nice to George, dear, won’t you?’ she went on. ‘Give him a chance to settle, eh?’ Tom nodded.

‘Where do you want those calves, Dad?’ he asked, bending down by the door to pull on his boots.

‘They’ll have to go down on the water-meadows until the winter, I reckon. And Tom, don’t forget to check the electric wire down there, will you? We don’t want them running around in the woods.’ His tone was gentler now. Tom felt it and warmed to it. The trouble was that he was too close to his father – they were too alike in many ways. He stamped his feet firmly into the bottom of his boots. ‘What about the milk this morning? Did you do all right?’ his father asked.

‘Not bad,’ said Tom, ‘just under two gallons. My wrists are still aching – they’ll never get used to it. I took my transistor over like you said and she seemed to like it, but I wish they wouldn’t give the news so often – Emma doesn’t seem to like it. I think she’s bored with it.’

‘Sensible cow,’ his father laughed.

‘Can I come?’ Storme was pushing the last crust of toast into her mouth. She always left the crusts till last, always had done. ‘I’ve finished,’ she said, wiping her mouth and chewing hard.

‘You can open gates if you like,’ said Tom. ‘I’ll see you down there.’

It was as if there had never been a row – better in a way, he thought. He hardly ever thought about his parents unless he’d had a quarrel. He smiled at them and shut the kitchen door behind him. It was blazing hot already and he stood for a moment squinting in the sunlight, then he scuffed his way across the yard, climbed the gate by the Dutch barn and sauntered slowly down the track towards the water-meadows. He kicked at a large piece of silver-black flint that lay in his path, unbuttoned his shirt and wondered about George.

George looked out of the window of the Mini; there was nothing else to do. The grass and the white heads of the hogweed leaned over into the lane ahead of them and bent suddenly in the wind that the car made as it passed. The radio prattled on: ‘Well, well, welcome all you lovely people out there on this sunny, sunny day. And for a sunny day, let’s all of us listen in to the new sunny sound of “Tin Pan O’Malley” in their amazing, chart-topping new release . . .’ Mrs Thomas turned down the volume a little and smiled at him. He liked Mrs Thomas; she was one of the few people he’d known all his life. He was glad she’d stopped trying to talk to him, but she was always good that way.

The familiar dread of meeting new people welled up inside him. He bit at his knuckle until it brought the tears to his eyes. If only she’d turn round and go back.

‘How much further?’ he asked.

‘Not far now,’ she said. ‘Two or three miles – won’t be long.’

George studied the grooves his teeth had made in his knuckle and the music changed to the hiss of static as they passed under a mesh of electric wires.

George looked out of the window again for the first glimpse of yet another home.

CHAPTER 2

THE CAR RATTLED OVER A CATTLE GRID, AND MRS Thomas slowed down to a crawl, struggling with the gear lever.

‘This is it, George,’ she said. ‘Just down the bottom of the drive,’ and the car bobbed and rocked in the craters and ridges of the farm track that led downhill towards a cluster of buildings. George was thrown violently against the door as the Mini keeled over in a rut.

‘Sorry about that,’ said Mrs Thomas, who was clinging to the wheel rather than driving. ‘You all right? It’s worse every time I come here.’

George rubbed the side of his head and stiffened himself for the next crater. It was then that he caught sight of a dark-haired girl, sitting on a gate-post in front of the buildings.

Storme watched the car rocking down the track towards her leaving a trail of dust rising into the air behind it. She hadn’t been waiting long. She’d become bored with standing in the sun, holding gates for Tom; and anyway she always liked to see the foster children first – a sort of sneak preview so that she could run in and tell everyone what he was like. She jumped down off the gatepost and tried to make out the features of the boy in the passenger seat, but there was too much dust and the car was still too far away.

‘Who’s that?’ George asked.

‘That’s the girl I told you about, remember? That’s Storme. Looks as if she’s been waiting for you.’

The car ground to a halt in the gravel and Storme came towards the car, waving the dust cloud away from her face. She bent down by Mrs Thomas’ window.

‘Is that him?’ she said.

‘Hullo, Storme,’ said Mrs Thomas, smiling at Storme’s bluntness. ‘This is George. George, this is Storme.’

Storme peered across Mrs Thomas and scrutinised George, who stared back. Like a parcel, he thought, it’s just like a postman delivering a parcel.

‘Your mum and dad?’ Mrs Thomas felt for George. ‘Are they in the house?’

‘Think so,’ said Storme, who was beaming at George by now. ‘You drive up. I’ll go and tell everyone he’s here.’

George watched her run off shouting at the top of her voice. ‘Always the same,’ he muttered. ‘They always stare at you.’

‘Come on, George,’ said Mrs Thomas. ‘She’s only young. She’s interested, that’s all; and after all, you are a new face.’

The car bumped across the farmyard scattering ducks and chickens in all directions and disturbing a sparrow that was having a dust-bath in one of the ruts. The car pulled up with a jerk. She turned off the engine.

‘Do try to enjoy yourself, George,’ she said before she opened the door, but George wasn’t listening. He was absorbed by a white duck that was waddling away from the car, sideways like a crab, keeping one eye on him and the other on the chorus of indignant hens in front of her. The main flock of ducks huddled together in noisy confusion against a brick wall: this one quacked out her own special defiance. George winked at her. She seemed offended and waddled off, bottom-heavy and cumbersome, towards the pond.

And then he was standing beside the hot car and Mrs Thomas was smiling thinly and making the introductions. Storme was clutching her mother’s hand, pulling her forward, and her father trailed along behind. They were all smiling at him. No one said anything. There were some sheep bleating in the distance and a chicken jerked its way between George and the car, pecking at the dust and warbling softly to herself. George felt hot and wondered what to do with his hands.

‘I saw him first, Mum. I told you I would,’ said Storme, still beaming at him.

‘Hullo, George,’ said the smiling lady in the apron. ‘You’re a bit early. Caught us on the hop – but no matter, it’s lovely you’re here.’

‘Better early than late, lad,’ the man said, taking George’s suitcase from Mrs Thomas. George’s white duck had come back and was standing by the car, watching. George was relieved to have something else to look at. ‘Tom’s not here at the moment,’ Storme’s father went on. ‘Still out with the calves, I shouldn’t wonder.’ George stared back at his duck and wondered if ducks ever blinked.

‘Shall we go and get him?’ said Storme, trying to make George look at her. She wondered what he saw in the duck.

‘That’s a good idea,’ Mrs Dyer said. ‘He’s down in the water-meadows somewhere, and we’ll give Mrs Thomas a cup of coffee – all right?’ George nodded and tried a smile that didn’t happen.

Storme didn’t have to be asked twice. ‘Come on,’ she said, and ran past him. George looked at Mrs Thomas who smiled and then walked away with Mr and Mrs Dyer. They’d be talking about him. ‘Come on,’ Storme was shouting at him from the gate. They climbed over and walked down the dusty track towards the water-meadows.

‘Mind the cows,’ said Storme, pointing at the ground by George’s feet. The warning was only just in time and George managed to lengthen his stride and avoid the huge cowpat that was spread out at his feet. He looked at her and they both laughed together. Then a fly was after him, buzzing round his ears. He swiped at it, but that just seemed to encourage it.

Storme was prattling on. ‘Tom’s been chasing calves around all morning.’ She was chewing a long piece of yellow grass. ‘Last time I saw him, he was all hot and cross. He came back in for a drink just before you came – grumbling about the flies. And do you know? He said his favourite meat was veal. I don’t think that’s very funny, do you?’

George looked down at her and listened; she never gave him a glance. She could have been talking to herself, until she said suddenly, ‘The girl we had last year, she didn’t like it here very much.’

‘What girl?’ George asked.

‘Jenny. She was the one we had last time. Mrs Thomas brought her as well. She always brings them. Do you like her?’

‘Who?’

‘Mrs Thomas,’ Storme said, scuffing her feet in the ruts and creating a dust storm round her ankles.

‘She’s all right,’ George said. ‘You have someone every summer, do you?’

‘Oh, yes,’ she went on. ‘I don’t mind much, but Tom doesn’t like it.’ George shook his head against the fly and swiped at it again.

‘I hate flies,’ he said.

‘Lots of them here,’ said Storme. ‘They like the animals, see. You’ll get used to them.’ She pointed ahead of her and George followed her arm. ‘There he is,’ she said, and she ran down the track, leaping like a goat from rut to rut. George could see only the top half of Tom; the rest was hidden by the calves that were milling around him.

‘Tom! Tom!’ she shouted, leaning over the gate and cupping her hands to her mouth. ‘It’s George! He’s here!’ Tom waved back from the bottom of the field.

George looked at Storme standing on the bottom rung of the five-barred gate. This was something he had not met before: someone who was completely natural and open. She said just what came into her head; there were no pretensions, no inhibitions. He transferred his attention to the boy in dark jeans who was walking slowly towards them across the field followed closely by a small black and white calf.

‘Still looks cross,’ said Storme. ‘And that’s Jemima behind him. Only three months old she is, and she sucks anything she can get hold of.’ And she laughed as Tom slapped out behind him at the calf that was doing its best to suck the shirt out of his trousers.

Tom had seen them coming before Storme shouted to him. He’d been brooding about George all morning. His mind hadn’t been on the job. That was why he’d taken so long to bring the calves down into the water-meadows. Somehow Jemima had separated herself from the herd and skipped off before he could stop her. He’d herded the rest of them into the field and had to go back for Jemima. He’d found her munching away happily near the cattle grid at the top of the drive. All the way back down to the water-meadows he’d cursed Jemima and the heat and the flies, and particularly George.

And now here he was tramping reluctantly towards George and Storme, followed by the adoring Jemima who didn’t seem to understand that she wasn’t wanted. Tom hated meeting people anyway and by the time he got to the gate he still hadn’t thought of anything to say. But Storme solved that problem.

‘You caught her then?’ she grinned at him.

‘Yes,’ he said. The two boys looked briefly at each other, and then looked away. Neither could bring themselves to say anything.

Then Jemima was at his shirt again, and he turned and pushed her away. He was grateful for the intrusion – it gave him time to think of something to say.

‘Don’t do that,’ said Storme. ‘She loves you – you’ll hurt her feelings.’

‘She hasn’t got any,’ said Tom. ‘If she had, she wouldn’t have had me chasing up and down in the heat all morning, would she?’ He talked deliberately at Storme, but it was Jemima that finally forced the two boys to acknowledge each other. Repeatedly rejected, Jemima left Tom’s shirt and swayed towards George and before he could move, he felt a sharp tug at his trouser leg and looked down. He was being sucked at noisily. He pulled his leg away from the gate, but Jemima pushed her head further through the bars so that George had to step back quickly to avoid her. Storme leaned across offering her hand to Jemima who took it and sucked on it hungrily.

‘Like sandpaper, her tongue. Almost sucks your hand off,’ said Storme, pulling her hand away and wiping the saliva off on the grass.

‘I didn’t know they were so friendly,’ said George, now safely out of reach of the grey tongue that was still curling out like a tentacle in search of something or someone to suck.

‘They’re not,’ said Tom. ‘This one’s odd – doesn’t like cows at all, just people.’ They looked at each other as they spoke and then back at Jemima. Jemima pulled her tongue in and looked up at them with her great gentle eyes. ‘Do I look like your mother?’ Tom asked Jemima. ‘Is that it?’ They were all laughing now. Jemima blinked dreamily up at him, stretched her neck upwards and out came the tongue again, but Tom sidestepped her and climbed the gate. They left her forlorn and disappointed, her white head thrust through the gate.

By the time they reached the house, Mrs Thomas had gone. George half-expected it anyway – it was a favourite trick of hers that he knew well by now. She would leave without really saying goodbye, but this time it didn’t seem to matter to him that much.

After lunch Storme took him up the dark, narrow staircase to his room at the top of the house, and during the afternoon he helped to unload hay-bales from the trailer and stack them in the Dutch barn with Tom, Storme and Mr Dyer. Storme didn’t do much – she just talked. The sun shimmered hot behind a layer of cloud, and as the afternoon went on the air became heavy and the work more exhausting. Storme gave up her chatter and went inside; the hay was tickling her and she couldn’t stop coughing and spluttering in the dust thrown up by the bales as they hit the ground.

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.