Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Charlotte Mew: and Her Friends"

Dedication

In memory of

THE POETRY BOOKSHOP

Contents

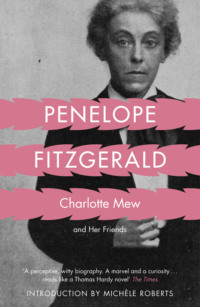

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

Introduction

1: The Day of Eyes

2: Love between Women

3: Lotti

4: ‘These I Shall See’

5: A Yellow Book Woman

6: The China Bowl

7: Nunhead and St Gildas

8: Rue Chateaubriand

9: The Quiet House

10: The Farmer’s Bride

11: Mrs Sappho

12: May Sinclair

13: ‘Never Confess’

14: The Poetry Bookshop

15: Alida

16: ‘J’ai passé par là’

17: Sydney

18: The Shade-Catchers

19: Delancey Street

20: The Loss of a Mother

21: The Loss of a Sister

22: Fin de Fête

Selected Poems of Charlotte Mew

The Farmer’s Bride

In Nunhead Cemetery

The Changeling

Ken

A Quoi Bon Dire

The Quiet House

Madeleine in Church

The Shade-Catchers

Saturday Market

Sea Love

From a Window

Not for that City

Fin de Fête

I so liked Spring

The Trees Are Down

Appendix: A Note on the Poetry Bookshop Rhyme Sheets

Select Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Notes and References

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Penelope Fitzgerald

Preface by Hermione Lee, Advisory Editor

When Penelope Fitzgerald unexpectedly won the Booker Prize with Offshore, in 1979, at the age of sixty-three, she said to her friends: ‘I knew I was an outsider.’ The people she wrote about in her novels and biographies were outsiders, too: misfits, romantic artists, hopeful failures, misunderstood lovers, orphans and oddities. She was drawn to unsettled characters who lived on the edges. She wrote about the vulnerable and the unprivileged, children, women trying to cope on their own, gentle, muddled, unsuccessful men. Her view of the world was that it divided into ‘exterminators’ and ‘exterminatees’. She would say: ‘I am drawn to people who seem to have been born defeated or even profoundly lost.’ She was a humorous writer with a tragic sense of life.

Outsiders in literature were close to her heart, too. She was fond of underrated, idiosyncratic writers with distinctive voices, like the novelist J. L. Carr, or Harold Monro of the Poetry Bookshop, or the remarkable and tragic poet Charlotte Mew. The publisher Virago’s enterprise of bringing neglected women writers back to life appealed to her, and under their imprint she championed the nineteenth-century novelist Margaret Oliphant. She enjoyed eccentrics like Stevie Smith. She liked writers, and people, who stood at an odd angle to the world. The child of an unusual, literary, middle-class English family, she inherited the Evangelical principles of her bishop grandfathers and the qualities of her Knox father and uncles: integrity, austerity, understatement, brilliance and a laconic, wry sense of humour.

She did not expect success, though she knew her own worth. Her writing career was not a usual one. She began publishing late in her life, around sixty, and in twenty years she published nine novels, three biographies and many essays and reviews. She changed publisher four times when she started publishing, before settling with Collins, and she never had an agent to look after her interests, though her publishers mostly became her friends and advocates. She was a dark horse, whose Booker Prize, with her third novel, was a surprise to everyone. But, by the end of her life, she had been shortlisted for it several times, had won a number of other British prizes, was a well-known figure on the literary scene, and became famous, at eighty, with the publication of The Blue Flower and its winning, in the United States, the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Yet she always had a quiet reputation. She was a novelist with a passionate following of careful readers, not a big name. She wrote compact, subtle novels. They are funny, but they are also dark. They are eloquent and clear, but also elusive and indirect. They leave a great deal unsaid. Whether she was drawing on the experiences of her own life – working for the BBC in the Blitz, helping to make a go of a small-town Suffolk bookshop, living on a leaky barge on the Thames in the 1960s, teaching children at a stage-school – or, in her last four great novels, going back in time and sometimes out of England to historical periods which she evoked with astonishing authenticity – she created whole worlds with striking economy. Her books inhabit a small space, but seem, magically, to reach out beyond it.

After her death at eighty-three, in 2000, there might have been a danger of this extraordinary voice fading away into silence and neglect. But she has been kept from oblivion by her executors and her admirers. The posthumous publication of her stories, essays and letters has now been followed by a biography (Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life, by Hermione Lee, Chatto & Windus, 2013), and by these very welcome reissues of her work. The fine writers who have done introductions to these new editions show what a distinguished following she has. I hope that many new readers will now discover, and fall in love with, the work of one of the most spellbinding English novelists of the twentieth century.

Hermione Lee

2013

Introduction

A true poet is first of all appreciated by his or her peer group. Critical recognition usually arrives afterwards. Charlotte Mew’s work was admired by writer contemporaries such as Siegfried Sassoon, Thomas Hardy and Virginia Woolf. Hardy said: ‘She is far and away the best living woman poet, who will be read when others are forgotten.’ Virginia Woolf said: ‘I think her very good and interesting and unlike anyone else.’

Mew’s words, coming powerfully alive on the page, also electrified audiences when she read her poems aloud. Penelope Fitzgerald, writing this biography, comments: ‘she seemed not so much to be acting or reciting as a medium’s body taken over by a distinct personality.’ Poetry in performance was relished in the early twentieth century as it is now, a hundred years later. The equivalent of our open mic poetry slam happened in the Poetry Bookshop in Bloomsbury, decorated with hand-coloured poetry posters, hung with curtains of sacking. People packed into the upstairs room and listened by candlelight. Between 1913 and 1920 you could attend readings by writers as diverse as Rupert Brooke, D. H. Lawrence, Edith Sitwell, Eleanor Farjeon, Anna Wickham and W. B. Yeats (among many others). Alida Monro did much of the work of the bookshop, alongside her poetry-publisher husband Harold. She often gave readings of the work of absent poets. She loved Mew’s poems, and in November 1915 invited Mew to come and hear her read them. Thus their long friendship began.

Mew, signalling her originality and difference through her words, also did so through her hoarse voice and her distinctive clothes. A tiny figure in a plain dark coat and skirt, severely cut, she sported a white shirt and black cravat, red stockings on occasion, and wore her hair cut short. She rolled her own cigarettes. She had an oval face, and huge eyes, which blaze out at us from her photographs.

Growing up in the aspirant London middle class, child of a struggling-architect father and snobbish mother, Charlotte was required to appear ladylike, decorative and genteel. However, her family’s financial misfortunes after her father’s death meant that she also needed to make a living. Like many another ambitious young woman before and after her, she decided to earn money by writing. She had an ailing mother to look after, housework to do, lodgers to tend, but she carved out a space in which to create short stories and poems. She travelled, too, in northern France, and explored new freedoms abroad, including trying out dancing the can-can, and hanging out with the sailors loafing along the quays. She fell passionately in love more than once, and endured the bitterness of sexual rejection. She made few but close friendships, with people who respected her shyness and contradictoriness.

These friends gave her the encouragement every writer needs to go on writing. The ruthless drive to create may be experienced as an internally produced one, but needs external validation too. This is probably even more true if you are breaking moulds, as Mew did. Coming after the Victorians and before the modernists, she invented a new music in poetry, a new kind of line, irregular and urgent, employing monologue forms, voices (often male) whose utterances seem to echo free-association, irregular rhythms that thump like the blood of a disturbed heart. The poems dramatise and rehearse themes of sexual longing and frustration, family crises, madness, creativity, childhood, cruelty. They are powerful, upsetting, whimsical, amoral.

A poet may become famous in his or her own day, then fade from sight when fame’s light swivels elsewhere. Time is conventionally supposed to tell whether someone’s work will last, to be admired afresh by future generations. In this view, history acts as a sort of sieve, reliably separating the wheat from the chaff. However, human agency is required alongside. If someone does not keep your name in the papers, your work in print, your books on the educational syllabus and in the literary canon, then your name may be temporarily forgotten, until you are rediscovered. Charlotte Mew, championed by distinguished male editors such as Harold Monro in her lifetime, was ignored by later ones, her poems left out of their anthologies; omissions which had the effect of falsifying and distorting the literary map. Nonetheless, Mew’s work went on being valued by successive waves of readers unafraid of appearing unfashionable. The scholar Val Warner produced a complete edition of her poems and prose in 1981. Then, in 1984, Penelope Fitzgerald published Charlotte Mew and Her Friends, which drew attention all over again to this remarkable writer. This reissue of that fine biography will, I hope, introduce a new generation to the fascinating, strange, vivid world of Mew’s poetic imagination.

Penelope Fitzgerald was writing fiction at the same time as working on her biography of Charlotte Mew, which allowed her to muse about how the two forms differed and overlapped. Her own biographer, Hermione Lee, quotes her joking: ‘On the whole I think biographers are madder than novelists.’ Fitzgerald also wrote: ‘I think you should write biographies of those you admire and respect, and novels about human beings who you think are sadly mistaken.’ She considered that fiction’s advantage over biography was that it could contain dialogue, which of course the writer made up. As a biographer, she was diligent with her research, committed to facts and to truth. As a novelist writing biography, she occasionally allowed herself to speculate in a minor way. For example, speaking of the death in childhood of Charlotte’s younger brother, she says: ‘Charlotte, at seven years old, was certainly brought in, as elder sisters were in the 1870s, to see her little brother “in death”.’ She offers no direct evidence for this, simply invites us to imagine an experience.

When you write fiction, you may try to create the subjective emotional truth of a character, the way she is for herself, thoughts and feelings constantly shifting and changing. You may try to imagine a character’s hidden, secret, inside world, composed of visual images, snatches of music, fragments of overheard talk, bits of memory, currents of physical feeling, all involved in a whirling dance. All this richness, linguistic and non-linguistic, has to be translated into connected words, put into sentences, arranged in narrative order, the timeless moment subdued to the constraints of time. Form and pattern emerge; the novel embodies the process of its making.

As a biographer, you necessarily work more from and on the outside. Fitzgerald respects Mew’s private self, and seems to be protective of it, even as she shows that her subject’s sense of privacy was linked to her sense of what the wider society could and could not tolerate. Mew desired and fell in love with women, but could not discuss her feelings; not even with a close friend such as Alida Monro. Since she was not a feminist, not even a suffragist, she was cut off from the friendship of the lesbian women who found each other through those political movements. On her trips to Paris she had no access to the lesbian coteries and salons that flourished there. Sooner or later she had to return to a world of constraints; and to sexual loneliness.

Some writers keep their patterns of disorder-into-order firmly inside themselves, firmly inside their rough drafts. Others need to live them out, to break away from limiting codes of conduct, take risks and make experiments. Outsiders, critics, looking at a writer’s apparently messy life and relationships, messy writing-room, may express uncomprehending disdain. But the writer, the poet, whether she prefers her mess to be metaphorical or literal, or a mixture of the two, needs to embrace her chaos. She needs to take inherited structures of grammar, inherited lexicons, break them up, see what she can make with them. She needs to play, both ferociously and tenderly; eagerly to destroy, patiently to rebuild. She may need to destroy, play with and reinvent inherited rules of relationship. On her own serious terms.

At considerable cost to herself, Charlotte Mew triumphed. She achieved the writing of poetry of beauty, originality and intensity. In a culture that regarded poetry as a supremely male vocation (niches were granted to poetesses writing ladylike verses) she made her voice heard.

How did she do it? Penelope Fitzgerald’s answer is that she divided herself in two. She maintained an outer, decorous, feminine persona, which Fitzgerald names Miss Lotti, the nice girl, passive and chaste, a disguise which hid the passionate, wilder persona, the artist, Charlotte, the ‘savage who threatened her from within’. As a survival technique, this proved exhausting: the divided self enacted a perpetual struggle, the ‘good’ self savagely fighting and punishing the ‘bad’ one. Perhaps this was an internalised version of battles begun in childhood. As a small girl, Charlotte Mew was taught gloomy Nonconformist piety by her nurse, for whom the human condition meant sin, judgement, rejection and guilt. Apparently she both loved and feared this nurse. How could she have escaped being damaged by her bleak, punitive, hell-threatening religion? Fitzgerald (herself a compassionate Anglican) does not explicitly suggest that Charlotte Mew’s inner struggle, one part of herself waging war on the other, may have acted out a version of the small girl’s drama with her nurse, but I let myself speculate that that is possible. In her later life Charlotte was described by one of her women friends and patrons as ‘a pervert’. What was perverse was the power relationship inflicted by the nurse.

Nonetheless, despite these wounds, out of them, Charlotte made unforgettable poems. The same puzzled friend was able to recognise her as a genius.

Penelope Fitzgerald’s biography is motivated not only by writerly admiration but also by sympathetic interest. Fitzgerald writes with just enough detachment: not too little and not too much.

A biographer certainly needs to be scholarly and patient; intellectually capable and alert; knowledgeable and well-read. Also, given that modern biographies deal so much with their subjects’ personal and emotional lives as well as their worldly achievements, a biographer needs to cultivate empathy. Empathy means to feel with. To feel with your subject on her own terms as well as yours. A biographer who is shocked or upset by unconventional behaviour, passionate emotion, apparently ‘childish’ desires and needs, may fall back on expressions of moral superiority, or may start scolding. Women who break out of what’s expected of them, in order to live and write differently and originally, are not saints, and should not be idealised in hagiographies, but neither should they be mocked, labelled as neurotic. Penelope Fitzgerald employs a tone I think of as characteristic, which we note when we read her reviews: sharply intelligent, wry, often humorous, always trying to be fair and non-judgemental.

The tone of this biography suggests an equal relationship between biographer and subject, one based neither on heroine-worship nor the need to dominate. It suggests the enactment of a relationship between friends, walking and talking, relishing together the comedy of the grubby London streets they both loved.

At the same time it functions occasionally as a kind of dark mirror of its author. We know from Hermione Lee’s biography of Penelope Fitzgerald that the latter was ‘adept at evasions and self-editing’, faced many difficulties in her domestic life, and drummed up quietly heroic courage to deal with them. From time to time, as she writes about Charlotte Mew, we glimpse Penelope Fitzgerald’s admiration of stoicism and reticence, and her understanding of the need for masks and concealment. This biography is necessarily a chronological narrative but it dramatises an eternal moment: one unconventionally minded woman recognises another, salutes the other, across the gap of years, as both different and similar. At the same time both writers beckon the reader to follow them into their coincident worlds.

Michèle Roberts

2014

CHAPTER ONE The Day of Eyes

THE MEWS came from the Isle of Wight. It was a common name all over the island and still is, but by 1832 when Fred Mew, Charlotte’s father, was born, his own branch of the family had settled near Newport. Some of them were carpenters and labourers, some were known to have bettered themselves. This was certainly true of Fred’s grandfather, Benjamin Mew, the brewer – who was a member of the corporation and a prime mover of the Carisbrooke Water Company, which brought Newport its first public water supply in the 1820s. One of Benjamin’s sons, Richard, farmed at Newfairlee, a mile or so to the north-east of Newport, while another one, Henry, kept the Bugle Inn in the High Street. Henry imported wine and spirits, with premises in both Newport and Cowes; the farm at Newfairlee supplied milk and vegetables for the guests at the Bugle and grazing for their carriage horses in summer. These profitable arrangements brought the two families very close. Fred was the seventh and youngest of Henry’s children, and for all of them ‘Theirn’ and ‘Ourn’ – the farm and the inn – were both home. Fred grew up largely at Theirn, over at Newfairlee.

Henry Mew, however, was determined not to put his sons into the licensed trade, but to send them to London to make their fortunes. George and James went first, and were set up in a small business. Fred was to be an architect, or rather something between an architect and a speculative builder. Evidently there was money in that. In the Island itself, Seaview Villas were going up all round the coast in response to the new holiday trade, and new Gothic churches were ready for them, including St Paul’s, Barton, where the Mew family worshipped on Sundays. Royal Osborne, five miles north of Newport, was begun in 1845 (when Fred was thirteen), and went forward in the charge of the great builder Thomas Cubitt (Queen Victoria’s ‘our Mr Cubitt’) over the next three years. It might have been thought, then, that a bright boy could be apprenticed and have good prospects without leaving the Island. But one of Fred’s uncles was already a partner in a London architect’s firm, Manning and Mew, at 2 Great James Street, Bedford Row. The firm seems not to have been particularly successful, but it had the great virtue of being ‘in the family’. Fred was despatched, and arrived at the age of fourteen straight from the sea breezes and cow pastures and the old-fashioned Bugle Inn to London’s East End. His elder brothers had a house off the Old Kent Road, and he was to be lodged there.

To begin with they sent him for a little further education to Mr Walton’s Albany House Academy, also in the Old Kent Road. Walton’s place was not quite as grand as it sounded, being a commercial school which gave a grounding in business correspondence, practical arithmetic and some Latin. After a year Fred’s father took him and paid the premium for his articles with Manning and Mew, where he was to learn architectural drawing, ‘improving’, and surveying, and to make himself useful on the sites.

The only building by which (if at all) Manning and Mew is remembered is the New School of Design at Sheffield (commissioned in 1856). The drawing for it, the only one which the firm ever exhibited at the Royal Academy, is by Fred. But in the following year he found himself a more hopeful position, transferring as architectural assistant to H. E. Kendall, Junior, of Spring Gardens, Trafalgar Square. Henry Edward Kendall called himself Junior, or H.E.K., out of respect for and to distinguish himself from his grand old father. This father, the son of a Yorkshire banker, had been a pupil of Thomas Leverton and a friend of Pugin. In the Gothic manner he had designed churches, prisons, workhouses and castles, helped to develop the fashionable Kemp Town district of Brighton, and later designed Mr Kemp’s own mansion in Belgrave Square. He was responsible, ‘wholly or in part’, to quote his obituary in The Builder, ‘for the houses of the Earls of Bristol, Egremont and Hardwicke’. Everything was done with spirit. Kendall was tall, distinguished and generous, loved dogs and guns, and continued to shoot even after he had blasted off his left hand in an accident. At a time when Thomas Hardy, it seems, had to sit through a sermon in Stinsford church against ‘the presumption shown by one of Hardy’s class in seeking to rise, through architecture, to the ranks of professional men’, and these professional men themselves weren’t always clearly distinguished from jobbing builders, Kendall was, without question, ‘gentlemanly’. One example was his conduct in the affair of Kensal Green Cemetery; in an open competition for the chapel he was awarded first prize for his Gothic design, and second for his ‘Italianate’. There seemed not much room for manoeuvre here, but the chairman, Sir John Paul, ignored the decision and ruled that his own design, which had won no prize of any kind, must be accepted and that Kendall should carry it out, which, with what was thought ‘very proper spirit’, he refused to do. By the 1850s he already had thirteen grandchildren and several great-grandchildren, and in his grey-haired dignity was known as ‘the Nestor of architects’.

The Bugle Inn, Newport High Street, where Charlotte Mew’s father was born in 1832.

Henry Mew’s trade card.

H. E. Kendall, articled to his father, loved him. He had more imagination than the old man, but was less confident, and partly suppressed it. They worked well together, and were both active in the ‘formation of an institute to uphold the character and improve the attainment of Architects’ which met, at first, at the Thatched House Tavern and Evans’ Cave of Harmony. These were the very early days of the R.I.B.A.

H.E.K. specialized in private houses, from a villa to a mansion, Board Schools, and lunatic asylums. In 1857, when he took Fred Mew, the country boy, into his office, he was also district surveyor for Hampstead, and a very busy man. The pages of his publication Kendall’s Modern Architecture, with its handsome illustrations, showed the clients exactly what to expect. Gothic was always in stock, but as tastes changed you could have Greek, Italian Renaissance, Early English (or Tudor), Jacobean, Queen Anne, or a combination of two or more. Several of the office’s pupils had distinguished themselves – for example, J. T. Wood, who discovered the remains of the Temple of Diana at Ephesus – but what was needed, with the 1860s in sight, was a hard-working young man who for a salary of fifteen shillings a week would make the working drawings and collect the details and ‘appropriate ornament’ which were the hackwork of the conscientious Victorian architect. Professional examinations were not compulsory until 1863, and Fred Mew never took any. He settled down to the assistant’s work in Spring Gardens. Although he was not without temperament – in fact he was given to occasional black depressions – he dedicated himself whole-heartedly to Kendall’s service. He left his lodging in his brother’s house, and took a room in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. This gave him only three miles to walk to work in the morning, a great improvement. Then, in 1859, Kendall nominated him as associate of the R.I.B.A.; old Kendall, in very shaky handwriting, supported the nomination. In 1860 Fred was made a junior partner.

Fred, in the old phrase, ‘filled a place’. H.E.K. had a son of his own, Edward Herne, who had been articled to him in the accepted family manner but, for reasons which were not talked about, had never finished his training. A nephew, Thomas Marden, had also been articled, but never practised. After these two failures, Fred became what he could never have expected to be, a confidant. When Kendall drew up his will he made Fred not a beneficiary, but a joint executor. In 1860 he offered him a junior partnership. Fred, on the strength of it, took the lease of a house, No. 30 Doughty Street, which was close to (though much less expensive than) Brunswick Square, where the Kendall family lived. The house, though modest, was too large for a single man, and it can hardly have surprised anyone when, early in 1862, he asked Kendall for the hand of his daughter.

Anna Maria Marden Kendall may perhaps have been in love with her father’s tall, countrified assistant, or she may have felt that, at twenty-six, she oughtn’t to let this chance slip. What is certain is that she was a tiny, pretty, silly young woman who grew, in time, to be a very silly old one. But she had the great strength of silliness, smallness and prettiness in combination, in that it never occurred to her that she would not be protected and looked after, and she always was.

The wedding took place at St George’s, Bloomsbury on December 19th 1863, and the witnesses were Henry Kendall, his sister Mrs Lewis Cubitt, and Sophia Webb, wife of the proprietor of the Fountain Inn, West Cowes. But Fred was not allowed to put down his own father’s profession as ‘innkeeper’. It was given as ‘Esquire’.

The intention is clear enough. As Anna Maria’s husband, Fred was of course bound to keep her in the style to which she was accustomed, and to do this he had, in the first place, to set about making himself into a gentleman. The architect’s profession, even though since the 1830s it had been organizing itself as something distinct from the building trade, was not, as has been said, able to do this quite on its own. Fred, it was recognized, was not likely to be anything up to his father-in-law. H.E.K. was on easy terms with his titled clients and with Bishop Wilberforce, to whom he had dedicated his Designs for Schools and Schoolhouses, Parochial and National. Mrs Lewis Cubitt, Anna Maria’s aunt, was married to the youngest brother in the famous firm, and though the Cubitts had been the sons of a Norfolk carpenter, look at what, through hard work and royal patronage, they had become! But Fred could at least see to it that he did not fall too far short. This pressure on him, as might be expected, came from the women. To Henry Kendall he was simply a young friend and assistant whom he liked, and could trust completely.

Mecklenburgh Square and Doughty Street, w.c.1. No. 30, where Charlotte Mew was born, is on the extreme right.

Fred took his bride to 30 Doughty Street, which he also used as a drawing-office. The house was narrow and steep between the basement kitchen and the attic nursery, but well placed at the end of the street, overlooking the airy plane trees of Mecklenburgh Square. Brunswick Square, with its far superior society and a mother always ready to listen to Anna Maria’s complaints, was only just round the corner, and Mrs Kendall took steps from the beginning to make sure that her daughter would hold the balance of power. From her own household she selected Elizabeth Goodman, a tall upstanding north-country-woman, a ‘treasure’, with all the value and inconvenience of treasures, an old-fashioned servant who asked for nothing beyond service and due reward, but whose prejudices could never be shifted, not by an inch. ‘She herself’, according to Charlotte, ‘came of very humble stock’, and had no book-learning, but somewhere she had learned perfect manners, ‘and, in speaking, an unusual purity of accent’ – ‘purer’, very likely, than Fred’s. Proud of her skill, proud even of her servant’s caps and aprons, which she made herself, she knew absolutely her moral and social role at 30 Doughty Street. She was to make life tolerable for her young mistress, who had married beneath her. Doughty Street was a comedown, but there are ways of managing everything. This did not, of course, mean any insubordination towards the master, quite the contrary; only there was a constant ‘making do’ and contrivancing of the boot-patching, collar-turning and left-over cold meat variety, which had never been necessary in Brunswick Square, and of which Fred cannot have been left unaware. When her wages were paid it was Elizabeth Goodman’s habit to buy a small present for everyone in the house ‘except the too exalted head’, that is to say, Fred, in his drawing-office on the second floor. No one in the house could in fact be too exalted for Elizabeth, who was in charge of everything, but in treating Fred as beyond the range of her little presents we may be sure that she kept him in his place. Through a ceaseless round of cooking, nursing and laundrywork she remained a stern ally of Anna Maria, and, by implication, a silent reproach to the man she had chosen to marry.