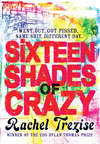

Buch lesen: «Sixteen Shades of Crazy»

Sixteen Shades of Crazy

Rachel Trezise

For Gwyn Thomas (1913–1981)

‘Perhaps when we find ourselves wanting everything, it is because we are dangerously near to wanting nothing.’

Sylvia Plath

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

Acknowledgements

Also by Rachel Trezise

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

They looked like any other group of twenty- and thirty-somethings, living the salad days of their lives, organs plump and red and juicy like the insides of ripe tomatoes, minds crisp like iceberg lettuce, sex powerful and biting like onion. Just another Saturday night at the Pump House, laughing big belly laughs, torsos bowed against the edge of the table as they concealed their illicit activities from the bar-staff, treasure moving around as if they were playing pass-the-parcel, the smell of perfume and alcohol shrouding their bodies like vinaigrette.

Ellie held the baggie in her fingers, fiddling with the knot, the plastic slippery with perspiration. Nowadays, street dealers were only concerned with their fleeting profits. There was no time for presentation. Nobody used paper wraps any more. She pushed her fingertip into the powder, kept it there for as long as it was polite, maybe longer, then smeared it over her taste buds, absorbing the sweet, glucosic tang.

‘What do they call this in America?’ she said, cheeks already tingling with anticipation. The south Wales valleys had been empty of soft drugs for eighteen months, no amphetamine, no MDMA. The new police chief had declared war on the B and C classes. Zero-tolerance policies sent all of the Drug Squad’s manpower to intercept shipments of party-starters in Bristol, while savvy London traffickers cruised the M4, Mercedes loaded with kilo packages of Afghan opiates. The skeletons of mining towns were populated by zombies, kids so thin and hopeless the wind would blow them over. Smackheads congregated in the gulleys, needles poised; the way women used to meet for chapel with their leather-bound bibles, honest-to-goodness recreational users left with nothing.

Ellie felt like an adolescent again, doing drugs for the very first time, a glorious thrill in her blood. ‘Is it crystal meth?’ she said, ‘or is that something totally different?’

Rhiannon snatched the baggie and balanced it in her lap. ‘Ooh cares?’ she said. She sprinkled a pinch of the powder into her wineglass. It was Rhiannon’s special wineglass, an unusual, egg-cup-shaped goblet that she demanded on every visit. She reached for another thumbful of the powder, her enthusiasm forcing the bag into the dip between her bare legs, an inch away from the hem of her new miniskirt. She was closer to forty than thirty; too old to wear that skirt, a shadow of a moustache on her top lip. Her hair was black, short and spiky, her eyes a soft, bovine brown. She had a huge laugh, like a drag artist’s. One of the stories about Rhiannon was that she’d been walking through Cardiff at three in the morning when some Grangetown wide-boy tried to drag her into an alley. She’d pulled a knife out of her handbag and slashed the tip of his nose clean off, left him for dead. It gave her a precarious allure that attracted weak men – men like Marc, who wanted to be neglected. There were lots of stories about Rhiannon, every one of them involving the opposite sex. Andy reckoned she’d married an octogenarian at eighteen, given him a heart attack in the bedroom; something he’d heard on a building site in Bridgend. The locals on the Dinham Estate said she’d made a pornographic video with Tommy Chippy for thirty quid, some of them swore they’d seen it; Rhiannon lying naked across the counter, eyes blacked out with tape, deep-fat fryers sizzling away in the background. All Ellie knew for sure was that she was a manipulative bitch; she hated women and women hated her.

‘Billy Whizz we call it in Wales,’ she said, hooting. ‘That’s where ewe live, El. Wales.’ She never overlooked an opportunity to remind Ellie where she was, because she knew Ellie wanted to be elsewhere, beneath the skyscrapers of New York. Rhiannon had resigned herself to a monotonous existence in the Welsh gutter, and no one else was allowed to look up at the stars.

The pub door opened. Rhiannon quickly balled the plastic into her fist. Big Barry the Disco came in and heaved his amplifier towards the squat stage, sweat stains forming under his yellow trouser braces. ‘The bloody prodigals’ return again, is it?’ he said as he shuffled past the boys.

Marc took the parcel from Rhiannon and hurriedly opened it on the table. ‘Just what the doctor ordered,’ he said, rubbing his hands together, a grin from ear to ear. He was wearing the same Liverpool football jersey he always wore, his chocolate-colour hair clipped close to his skull, receding quickly at the forehead. He was a genial man, the bassist and lead singer of a punk band called The Boobs. They’d been on a toilet circuit tour of Scotland, sleeping on the hard floor of their Transit van for six weeks, fighting for space amongst their beaten up guitars and drum-kit. They did this every five months or so, despite the lack of a record company, a tour agent, or even a cult fan base. They tossed every pound they made into the venture, as though their lives depended on it, and in Aberalaw their absence gave them the illusion of success. The stupid hacks at the local newspaper seemed to think they spent half of the year in their Malibu beach homes. Old women approached Ellie in the post office and asked her, ‘How are your Boobs doing?’

The band had got home earlier that day to the news that John Peel had listened to a demo they’d thrown at him through a backstage fence at last year’s Glastonbury Festival. He’d invited them to record a live session for the radio. Marc was happy as hell. He scoffed a whole gram of the powder, chasing it around his mouth with his roving tongue.

‘Sweetheart!’ Rhiannon barked, seizing the baggie from his hand and pushing it along the table. ‘Take it easy, will ewe? Ewe’re tiling the downstairs toilet tomorrow, remember?’

‘There’s hardly any left now,’ Griff said. Griff was the drummer, a fat, proud man with neon-orange hair; the bumptious disposition of a spoiled 12-year-old. His mother still made him corned-beef pie and salmon sandwiches to take-out on the road. He sullenly rubbed a small rock into his gum and then wiped his fingers on his check shirt, keeping the baggie in his hand, ensuring he had an audience for what he was about to say. Like a schoolboy carrying clecks to the dictatorial teacher, he looked sideways at Rhiannon. ‘He’s been a total arsehole all fucking tour,’ he said. ‘He stole a tray of muffins from Glasgow Services and kept them all to himself. He ate every bastard one and there were forty-eight of the fuckers. The only reason I’m staying in the band is because of this Peel session.’ He was always threatening to quit, and never did. ‘Should have seen the women in Scotland though,’ he said. ‘Lapped it up, they did.’

‘What women?’ Siân said. She whipped the baggie from him, turning it over in her hands. Siân was Griff’s wife. She hadn’t taken a narcotic since her first child was born. Three babies in as many years and she was down to a size twelve one week after each. No Caesareans, no stitches, no maternity leave. She worked at the video shop on a Tuesday and Wednesday and the Chinese takeaway on a Thursday and Friday – anything to keep the kids in shoes, since Griff wouldn’t lift a finger. Her glossy black hair reached down to the small of her back, framing her almond-coloured face. She had an enormous pink mouth. In any other place she would have grown up to be a catwalk model: long, sleek legs sauntering down a runway, an impossible pair of platforms on her flawless feet. But this was Aberalaw, and life wasn’t fair. She always looked like an advert for designer cosmetics, as though someone followed her around with a soft, pink light, no matter what kind of dive she was drinking in, no matter how drunk she got. In Ellie she never inspired envy as much as awe, the way people look at leopards roaming the Serengeti in David Attenborough documentaries; another species altogether.

‘I’m only joking,’ Griff said.

Siân passed the bag to Andy. ‘You’d better be,’ she said, staring at Griff, play-acting reproachful. ‘Six weeks you’ve been gone, and Niall started calling Bob the Builder Dad.’

‘It wasn’t like that,’ Andy said, whispering into Ellie’s ear. ‘There weren’t any girls.’ But Ellie already knew that. She’d been to too many gigs, carried too many microphone stands in and out of clubs. She’d danced on too many empty dance-floors; pretended not to know the band. Andy was no Keith Richards. But Siân was paranoid about groupies. Her days slipped away between school runs and fish fingers, and Griff was convinced he was God’s gift to starved pussy. Andy put his arm around Ellie, surreptitiously cupping one of her breasts. Ellie used her elbow to lock his hand in place. She enjoyed the warmth of his broad fingers; had missed him more this time than ever before. At night she’d woken up on the hour, every hour, waving her arm over the bedside table, searching for a pint of water that wasn’t there. He used to take one to her last thing at night, turning the lights out with his little finger. Without him around her, food was tasteless. Her sense of smell was defunct. But now she could smell the sweet fug of the rushed sex they’d had before leaving the house less than an hour ago. She imagined the ringlets of his protein swimming around inside her, life seeming once more like its happy, Technicolor self.

‘Are ewe takin’ any of that?’ Rhiannon said, pointing at the baggie in Andy’s lap.

Andy looked down at it, blond eyebrows scrunched to a frown. ‘Don’t you think we’re getting too old for it, Rhi? It’s full of toxins, you know.’

Rhiannon leaned over Ellie’s lap and grabbed it. She licked the inside of the bag, purple tongue thrashing against the cellophane. When it was clean she threw it in the ashtray. Everyone watched, eyes hopeless, as it slowly mingled in with the dust and dog-tabs, their first taste of phet for over a year.

Rhiannon lifted her wineglass. ‘Well, don’t look so bloody worried,’ she said. ‘Plenty more where that came from.’

2

It was a little after ten when the speed kicked in, dopamine rising to greet it; the time of night when life seemed full of possibility. Ellie was beginning to believe she was some sort of chemical Cinderella, blessed with wit and mystique. Big Barry was three-quarters of the way through the set-list Sellotaped to his sound desk. He’d been using the same one since he’d started the job in the late Eighties, only ever deviating to play the current number one. Rhiannon sprang to her feet when the piano intro to ‘I Will Survive’ began, drink splashing out of her glass. She headed for the walkway in front of the stage, extended chest bouncing against her ribcage. She stood facing the DJ, tight skirt preventing any real dancing, go-go boots slipping on the carpet, the other customers glaring at her. Generally, people either tolerated or detested Rhiannon. Any friends she’d ever had, she’d pissed off years ago.

‘Come on, girls,’ she said, shouting back at the table. She clapped her hands, the brass wall plates behind her shaking. This was the way Rhiannon moved; eyes screwed closed in devotion, hands held an inch away from her face, fatty palms smacking together, the slapping noise reverberating around the room. She stole Big Barry’s microphone and held it in her clenched fist. ‘Come on, girls,’ she said. ‘I wanna fuckin’ dance.’

Siân lowered her eyes and sipped from her half-glass. ‘It’s your turn,’ she said, hissing across the table at Ellie.

Ellie shook her head; she didn’t want to dance, not with Rhiannon. A gust of energy had just detonated in the small of her back, driving tiny particles of euphoria around her throbbing bloodstream. She was having a lovely time just sitting down; she didn’t want to waste a minute of it.

Siân pushed herself out of her seat. ‘I come out at night to get away from the kids, not look after her. Why has it always got to be me?’ She flicked her long hair, folded her arms, walked slowly towards Rhiannon.

A small blonde woman came in carrying a chair from the games area. She placed it at the edge of the table, struggling not to hit anyone with any of its stocky legs. Ellie didn’t recognize her. She’d never seen her before. But Marc obviously had. He was beckoning her with his waving hand, smiling and shouting into her ear, using a folded beer-mat to wipe Rhiannon’s wine spills from the table. Soon, a man followed, a tall, skinny man with a mop of dark, tangled hair. He sat next to the woman and nodded perfunctorily, eyes the colour of coal. It was hard to tell how old he was; mid-thirties – older than Andy, younger than Rhiannon; a scattering of black stubble around a pouting, mauve mouth. There was a thick silver belcher chain resting on his collarbone and dark circles under his eyes, the colour of smudged kohl. Ellie gawped at him until he opened his cigarette packet and counted what he needed for a flash, running a clean fingernail along the top of the corks. He threw some on the soggy surface of the table and balanced a further two in the V of his fore and middle finger.

‘Anyone?’ he said – an accent, not Welsh, but familiar. He looked quickly at each of the faces around the table, but if he thought anything at all about them, his stoic face hid it. Ellie waited until all of the loose cigarettes were taken and then clipped one from his hand. She thanked him, but he ignored her, tossing the last one into his mouth, holding it between alabaster teeth while he lit it with the ferocious flame of his chrome Zippo. Ellie suddenly felt conscious of her appearance. She was no Cinderella. She had a round, plain, pale-skinned face, framed by dull brown hair, not platinum-blonde like her siblings or even golden-blonde like the woman he was with.

Rhiannon reappeared, jostling against the table, tipping more drinks. ‘What’s the matter with ewe, ewe fuckin’ sourpuss?’ she said. She slammed her body into the space next to Ellie. ‘That’s what speed is for, mun, dancing.’ She pointed at Andy. ‘Cheer up,’ she said. ‘E’s home now. Ewe can get ewer oats tonight.’ She lifted the egg cup to her moustachioed mouth and downed the modicum of wine left inside. ‘Next time he goes away, ewe wanna tell ’im to leave ewe a dildo. Marc bought me iss massive pink rampant rabbit, din’t ewe, love? Wouldn’t fit in ewer ’andbag, El.’

Ellie blushed, embarrassed not by Rhiannon’s crudeness, but by her memory of her quickie with Andy, the pair of them scrambling around the bedroom, tripping over one another’s clothes. The thought had seemed heady a few moments earlier, but now it felt like a burden.

Rhiannon turned to the new faces at the table, looked the strange man square in the eyes, said, ‘Where’s my fag ’en, mush?’ He took another cigarette out of his packet and passed it across the table. Rhiannon grabbed it and popped it into her mouth, leaned forward and waited for him to light it for her. She dived headlong into conversation, her screechy monotone blaring over the music, her twisted body preventing Ellie’s joining in. It was useless to try to talk over Rhiannon, so she sat back on the bench, stole intermittent glimpses of him as he answered Rhiannon’s relentless questions, his lips swiftly fastening and unfastening. Rhiannon was still leaning towards him, head inclined, steadily pushing her cleavage into his view. After a while she started touching, smoothing her hand along his forearm, slowly at first, and then faster, squeezing at his skin. Siân was staring at him too, her forefinger hooked in her mouth, stupefied by his beauty or his oddness or his audacity, it was hard to tell what. Nobody new had turned up at the Pump House since the last Millennium.

After a while Ellie became impatient, hungry for the man’s attention. She thought up jokes to tell him. Something her friend Safia had said at work the day before had amused her, not for its content but for Safia having repeated it; something about Jeremy Beadle measuring the size of his penis. ‘He decided it wasn’t very big,’ Safia’d said, ‘small in fact; although on the other hand it was effing massive.’ Ellie’d almost pissed herself. It was obviously something Safia had heard the print boys say, and without fully grasping its meaning had memorized, intending to impress Ellie. But was it good enough? Maybe if she thought of an alternative character – she didn’t want to admit to ever having watched someone as naff as Jeremy Beadle. Ordinarily she wouldn’t admit to owning a television, but she couldn’t think of anyone who was cool and had a shrunken hand. Suddenly Andy coiled his arm around her shoulder, and pulled her close to him. They stared at one another, the balls of their noses touching. His eyes were lovely: irises a cocktail of blue gemstones, sapphire and topaz intertwining. But Ellie quickly wrestled away from Andy, looked back at the ebony eyes of the outlandish foreigner.

He was still busy with Rhiannon, head cocked towards her unintelligible banter. Ellie gave up on the joke idea, thinking he’d laugh at her, not at it. The anxiety was creeping in. The amphetamine high was over. She could feel the comedown lying in wait, bad blood pumping through her veins, and she submitted to it, began to contemplate the overflowing ashtray.

Before the bell rang for stop-tap, the blonde woman leaned over the table and said something to Rhiannon, the white strobe light revealing a crater-shaped patch of pockmarks on her cheekbones. Ellie hoped she was issuing some kind of reprimand, but she knew she wasn’t when Rhiannon put her hand on the woman’s shoulder and pointed at the door on the other side of the room. ‘Down there, love,’ she said, ‘turn left.’ The woman walked timidly, head bowed. When she’d disappeared behind Big Barry, Rhiannon turned to Ellie. ‘Fuckin’ English!’ she said. ‘Ey’re like bloody rats. Ewe’re never a mile away from one an’ ’ey just keep on breeding. With a bit of luck she’ll be in the men’s now.’

There was a queue in the lounge so Ellie went into the bar to buy drinks. Two old men sitting on the ripped benches amidst the shabby flock wallpaper. The barman was hiding behind a tabloid newspaper, crude headline about the death of Saddam Hussein’s sons splashed across the front page. She ordered four house vodkas and two cans of Red Bull. It was a ritual Rhiannon had started when the band was in Poland. She’d come back from an impromptu visit to the bar with three trebles, and placed them on the table in front of Siân and Ellie with a rebellious wink. She’d only been with Marc for a few weeks and Ellie knew now the drink buying had been an attempt to procure the girls’ friendship. Rhiannon put too much faith in money and thought she could buy relationships; gift giving was a staple in her control-freakery. But back then she seemed charming and, when the boys had returned, the vodka custom had prevailed; a peculiar proclamation of their union, like a Freemason’s handshake.

Ellie balanced the cans in the crooks of her arms, the glasses hooked in her fingers. As she turned to walk away, she stepped into somebody, her stiletto heel stabbing the rubber toecap of a basketball boot. Instinctively, she knew it was the stranger. She jolted backwards, the weight of a glass falling from her grip. Then, in her bewildered attempt to catch it before guessing which direction it was going to take, she jumped back at him, stepping again on his foot.

‘Whoa!’ he said, catching her, his arms stretched out like Jesus, as though trying to counter all eventualities. He smelled of musk and petrol and faintly of smoke. The glass landed on a beer towel, the liquid trickling out, forming a small dark patch on the Terylene. The barman caught the glass before it rolled off the edge.

‘Sorry,’ Ellie said, cheeks beginning to burn.

‘It’s okay,’ he said. ‘Want another one?’ He let go of her body and stepped backwards, the sudden absence of his touch sending an amphetamine rush through Ellie’s spine. It smashed against her cranium like a pinball he had triggered. Something about him activated a weird animalism in Ellie, an acute hunger in her abdominal walls. Immediately, she wanted to touch him again, to feel the sensation one more time. She stepped away. ‘Where are you from?’ she said. She wasn’t from Aberalaw either. She knew what a difficult time he’d have settling in.

He picked the empty glass up, gripping it with his bony, icicle-like fingers. ‘Cornwall,’ he said, sniffing it. He put it back on the towel. ‘Did you want another?’

Ellie thought about the West Country accents that had surrounded her throughout her three-year stint at Plymouth University. She was homesick suddenly for nights out at the Pavilions, for morning strolls along the Barbican, for lunchtime editorial meetings at the student magazine. When she had lived in Plymouth, she had never been homesick for Wales. ‘If you don’t mind,’ she said, remembering herself. ‘That one was for your girlfriend anyway.’

The man smiled affectionately at her. ‘She is not allowed to drink vodka,’ he said.

Andy daren’t tell Ellie what she wasn’t allowed to drink. Around here, the women wore the trousers, not because Welsh women were in any manner advanced in feminist thinking, but because Welsh men were so indolent; too dozy for domestic altercations. She couldn’t decide if the man’s dominance over his girlfriend’s choice of beverage was sexist, or exotic. She smiled weakly, shrugged her shoulders. She walked back to the lounge, her arms scrunched around herself like wings, the cold glasses clutched against her prickly skin. She is not allowed to drink vodka. ‘What a wanker,’ she thought as she kicked the lounge door open, knowing even as she thought it that what she was experiencing was not abhorrence. It was allure. This was girl meets boy, big style; the token of acceptance she’d been about to present to his girlfriend was bankrupt, common sense pirouetting into the middle distance, vanishing like the spilt liquor.

The rest of the night slipped away between a long, drawn-out stomach-ache and ephemeral spasms of jealousy. The amphetamine high dulled to a dreary pain, winding leisurely around her stomach, like a washing machine on a wool cycle. All night Rhiannon wouldn’t stop talking to the man. She jabbered perpetually, head bobbing like a buoy on choppy water. Every time she touched his emaciated wrist, accidentally, but more often intentionally, Ellie felt envy solidifying like a lethal tumour, deep inside her. Occasionally, the man caught Ellie’s stare, his onyx eyes glassy now from the smoke. They rested on her for a few seconds, alert and apologetic, but then quickly moved on to his drink, or, unbearably, on to Rhiannon. But Ellie didn’t stop looking at him, not even when Andy tried to kiss or speak to her. And what she noticed, just before the couple unexpectedly stood up, waved and left, was that everyone else in the pub was staring at them too, craning their necks and gawking, because this was a south Wales valley village, and nobody ever left, and nobody new ever arrived. They were like aliens, that couple, swanning in with their accents and their pockmarks. They might as well have arrived in a silvery saucer-shaped spaceship. Nobody outside of their own table attempted to speak to them, to ask where they were from or what their business here was, again because this was Aberalaw, a south Wales valley town. Instead, the other customers peered, and peered, like a mob of meerkats standing on hind legs. Then, when the couple had gone, they all turned to one another and made up their own stories.