Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Charlie Bone and the Blue Boa"

First published in Great Britain 2004 by Egmont UK Limited

This edition published 2010

by Egmont UK Limited

239 Kensington High Street

London W8 6SA

Text copyright © 2004 Jenny Nimmo

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

ISBN 978 1 4052 2545 8

eBook ISBN 978 1 7803 1204 0

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Egmont is passionate about helping to preserve the world’s remaining ancient forests. We only use paper from legal and sustainable forest sources, so we know where every single tree comes from that goes into every paper that makes up every book.

This book is made from paper certified by the Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC), an organisation dedicated to promoting responsible management of forest resources. For more information on the FSC, please visit www.fsc.org. To learn more about Egmont’s sustainable paper policy, please visit www.egmont.co.uk/ethical.

For Gwenhwyfar, who found the boa, with love.

Books by Jenny Nimmo

Midnight for Charlie Bone

Charlie Bone and the Time Twister

Charlie Bone and the Blue Boa

Charlie Bone and the Castle of Mirrors

Charlie Bone and the Hidden King

Charlie Bone and the Wilderness Wolf

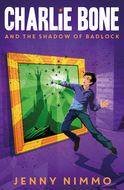

Charlie Bone and the Shadow of Badlock

Charlie Bone and the Red Knight

The Snow Spider trilogy

The Secret Kingdom

Secret Creatures

For younger readers

Matty Mouse

Farm Fun!

Delilah

Contents

Cover

Title page

Copyright

Dedication

Books by Jenny Nimmo

The endowed children

Prologue

1. Someone dangerous

2. The invisible boy

3. Runner Bean is rumbled

4. Sparkling stones

5. The shape-shifter

6. The starling

7. Uncle Paton’s return

8. A visit to Skarpo

9. A very old mouse

10. The wand

11. Bull, bells and golden bats

12. A sorcerer on the loose

13. The flames and a journey

14. The garden in Darkly Wynd

15. Lysander’s plan

16. The night of wind and spirits

17. Ollie and the boa

18. A belt of black jewels

The children of the Red King, called the endowed

| Manfred Bloor | Head boy of Bloor’s Academy. A hypnotiser. He is descended from Borlath, eldest son of the Red King. Borlath was a brutal and sadistic tyrant. |

| Asa Pike | A were-beast. He is descended from a tribe who lived in the Northern forests and kept strange beasts. Asa can change shape at dusk. |

| Billy Raven | Billy can communicate with animals. One of his ancestors conversed with ravens that sat on a gibbet where dead men hung. For this talent he was banished from his village. |

| Zelda Dobinski | Descended from a long line of Polish magicians. Zelda is telekenetic. She can move objects with her mind. |

| Lysander Sage | Descended from an African wise man. He can call up his spirit ancestors. |

| Tancred Torsson | A storm-bringer. His Scandinavian ancestor was named after the thunder god, Thor. Tancred can bring rain, wind, thunder and lightning. |

| Gabriel Silk | Gabriel can feel scenes and emotions through the clothes of others. He comes from a line of psychics. |

| Emma Tolly | Emma can fly. Her surname derives from the Spanish swordsman from Toledo, whose daughter married the Red King. He is therefore an ancestor to all the endowed children. |

| Charlie Bone | Charlie can travel into photographs and paintings. He is descended from the Yewbeams, a family with many magical endowments. |

| Dorcas Loom | An endowed girl whose gift is, as yet, undiscovered. |

The endowed are all descended from the ten children of the Red King; a magician-king who left Africa in the twelfth century, accompanied by three leopards.

Prologue

When the Red King left Africa, he took with him a rare snake, a boa, given to him by a travelling wise man. The boa’s skin was black and silver and its eyes like beads of jet. Sometimes, the shining eyes would close, but this was a deception. In the king’s presence the boa was eternally vigilant. No thief or assassin dared to pass it. The king, who could speak its language, regarded the boa as a friend, a guardian and a wise counsellor. He loved the creature dearly.

One day, while the king was absent on a hunting trip, his eldest son, Borlath, caught the boa in a net. Borlath had the cruellest heart of any man living, and his greatest sport was to torture. Within a week he had turned the wise and gentle boa into a creature that lived only to kill. It would squeeze its victims into oblivion within minutes.

The king’s daughter, Guanhamara, horrified by the boa’s new and deadly nature, rescued the creature and cast a spell, hoping to cure it. Alas, Guanhamara’s spell came too late and merely weakened the boa’s fatal hug. Its victims did not die, but they became invisible.

When Guanhamara died, the boa fell into a deep sleep. It shrivelled into a thing that was neither alive nor dead. Hoping one day to reawaken the creature, Guanhamara’s seven daughters (every one of them a witch) sealed the boa in a jar of liquid made blue with herbs. They also put in a bird with delicate, shiny wings. But the embalmed creatures were stolen by Borlath and passed down through his descendants, until Ezekiel Bloor, using a method recommended by his grandfather, managed to revive the boa whose skin had become a silvery blue. He was less successful with the bird.

Ezekiel was now a hundred years old. He had always longed to become invisible but, as far as he knew, the boa’s hug was permanent, and he didn’t dare to let the creature hug him. The old man still searched for a way to reverse invisibility, while the boa lived in the shadowy attics of Bloor’s Academy, keeping its secret, until someone could bring it the comfort of understanding – and listen to its story.

Someone dangerous

An owl swooped over the roof of number nine Filbert Street. It hovered above a running mouse and then perched on a branch beside Charlie Bone’s window. The owl hooted, but Charlie slept on.

Across the road, at number twelve, Benjamin Brown was already awake. He opened his curtains to look at the owl and saw three figures emerge from the door of number nine. In the pale street light their faces were a blur of shadows, but Benjamin would have known them anywhere. They were Charlie Bone’s great-aunts, Lucretia, Eustacia and Venetia Yewbeam. As the three women tiptoed furtively down the steps, one of them suddenly looked up at Benjamin. He shrank behind the curtain and watched them hurry away up the road. They wore black hooded coats and their heads tilted towards each other like conspirators.

It was half past four in the morning. Why were the Yewbeam sisters out so early? Had they been in Charlie’s house all night? They’ve been hatching some nasty plot, thought Benjamin.

If only Charlie hadn’t inherited such a strange talent. And if only his great-aunts hadn’t got to know about it, perhaps he’d have been safe. But when your ancestor is a magician and a king, your relations are bound to expect something of you. ‘Poor Charlie,’ Benjamin murmured.

Benjamin’s big yellow dog, Runner Bean, whined sympathetically from the bed. Benjamin wondered if he’d guessed what was going to happen to him. Probably. Mr and Mrs Brown had spent the last two days cleaning the house and packing. Dogs always know something is up when people start packing.

‘Breakfast, Benjamin!’ Mrs Brown called from the kitchen.

Mr Brown could be heard singing in the shower.

Benjamin and Runner Bean went downstairs. Three bowls of porridge sat on the kitchen table. Benjamin tucked in. His mother was frying sausages and tomatoes and he was glad to see that she hadn’t forgotten his dog. Runner Bean’s bowl was already full of chopped sausage.

Mr Brown arrived still singing and still in his dressing- gown. Mrs Brown was already dressed. She wore a neat grey suit and her straight straw-coloured hair was cut very short. She wore no jewellery.

Benjamin’s parents were private detectives and they tried to look as inconspicuous as possible. Sometimes, they wore a false moustache or a wig to disguise themselves. It was usually only Mr Brown who wore the false moustaches, but on one occasion (an occasion Benjamin would like to forget), Mrs Brown had also found it necessary to wear one.

Benjamin’s mother swapped his now empty bowl for a full plate and said, ‘You’d better take Runner across to Charlie as soon as you’ve cleaned your teeth. We’ll be off in half an hour.’

‘Yes, Mum.’ Benjamin scoffed down the rest of his breakfast and ran back upstairs. He didn’t tell his mother that Charlie hadn’t actually agreed to look after Runner Bean.

The Browns’ bathroom overlooked Filbert Street and while Benjamin was brushing his teeth, he saw a tall man in a long black coat walk down the steps of number nine. Benjamin stopped brushing and stared. What on earth was going on in Charlie’s house?

The tall man was Paton Yewbeam, Charlie’s great-uncle. He was wearing dark glasses and carried a white stick. Benjamin assumed the dark glasses had something to do with Paton’s unfortunate talent for exploding lights. Paton never appeared in daylight, if he could help it, but this was an extraordinary time to be going out, even for him. He walked up to a midnight blue car, opened the boot and carefully placed the wand (for that’s what it was) right at the back.

Before Benjamin had even rinsed his toothbrush, Charlie’s uncle had driven off. He went in the opposite direction to his sisters, Benjamin noted. This wasn’t surprising as Paton and his sisters were sworn enemies.

‘You’d better go over to Charlie’s,’ Mrs Brown called from the kitchen. Benjamin packed his pyjamas and toothbrush and went downstairs.

Runner Bean’s tail hung dejectedly. His ears were down and his eyes rolled piteously. Benjamin felt guilty. ‘Come on, Runner.’ He spoke with an exaggerated cheerfulness that didn’t fool his dog for one minute.

The boy and the dog left the house together. They were best friends and Runner Bean wouldn’t have dreamt of disobeying Benjamin, but today he dragged his paws very reluctantly up the steps of number nine.

Benjamin rang the bell and Runner Bean howled. It was the howl that woke Charlie. Everyone else in the house woke briefly, thought they’d had a nightmare and went back to sleep.

Charlie, recognising the howl, staggered downstairs to open the door. ‘What’s happened?’ he asked, blinking at the street lights. ‘It’s still night, isn’t it?’

‘Sort of,’ said Benjamin. ‘I’ve got some amazing news. I’m going to Hong Kong.’

Charlie rubbed his eyes. ‘What, now?’

‘Yes.’

Charlie stared at his friend in bewilderment and then invited him in for a piece of toast. While the toast was browning, Charlie asked Benjamin if Runner Bean would be travelling to Hong Kong with him.

‘Er – no,’ said Benjamin. ‘He’d have to be quarantined and he’d hate that.’

‘So where’s he going?’ Charlie glanced at Runner Bean and the big dog gave him a forlorn sort of smile.

‘That’s just it,’ Benjamin said, with a slight cough. ‘There’s no one else but you, Charlie.’

‘Me? I can’t keep a dog here,’ said Charlie. ‘Grandma Bone would kill it.’

‘Don’t say that.’ Benjamin looked anxiously at Runner Bean, who was crawling under the table. ‘Now look what you’ve done. He was upset already.’

As Charlie began to splutter his protests, Benjamin quickly explained that the Hong Kong visit had been a complete surprise. A Chinese billionaire had asked his parents to trace a priceless necklace that had been stolen from his Hong Kong apartment. The Browns couldn’t resist such a well-paid and challenging case but as it might take several months, they did not want to leave Benjamin behind. Unfortunately this didn’t apply to Runner Bean.

Charlie slumped at the kitchen table and scratched his head. His bushy hair was even more tangled than usual. ‘Oh,’ was all he could say.

‘Thanks, Charlie.’ Benjamin shoved a large piece of toast into his mouth. ‘I’ll let myself out.’ At the kitchen door he looked back guiltily. ‘I’m sorry. I hope you’ll be all right, Charlie.’ And then he was gone.

Benjamin was so excited he had forgotten to tell Charlie about his uncle and the wand, or the visit of his three aunts.

From the kitchen window Charlie watched his friend dash across the street and jump into the Browns’ large green car. Charlie lifted his hand to wave, but the car drove off before Benjamin had seen him.

‘Now what?’ mumbled Charlie.

As if in answer, Runner Bean growled from beneath the table. Benjamin hadn’t thought to leave any dog food for him, and Mr and Mrs Brown were obviously far too busy to think of such mundane items.

‘Detectives!’ he muttered.

For five minutes Charlie struggled to think how he was going to keep Runner Bean a secret from Grandma Bone. But thinking was exhausting so early in the day. Charlie laid his head on the table and fell asleep.

As luck would have it, Grandma Bone was the first person downstairs that morning. ‘What’s this?’ Her shrill voice woke Charlie with a start. ‘Sleeping in the kitchen? You’re lucky it’s Saturday. You’d have missed the school bus.’

‘Um.’ Charlie blinked up at the tall, stringy woman in her grey dressing-gown. A snowy pigtail hung down her back and it swung from side to side as she began to march about the kitchen, banging on the kettle, slamming the fridge door and plonking hard butter on the counter. Suddenly she swivelled round and stared at Charlie. ‘I smell dog,’ she said accusingly.

Charlie remembered Runner Bean. ‘D-dog?’ he stammered. Luckily, the heavy tablecloth hung almost to the ground and his grandmother couldn’t see Runner Bean.

‘Has that friend of yours been here? He always smells of dog.’

‘Benjamin? Er – yes,’ said Charlie. ‘He came to say goodbye. He’s going to Hong Kong.’

‘Good riddance,’ she grunted.

When Grandma Bone went into the larder, Charlie grabbed Runner Bean’s collar and dragged him upstairs.

‘I don’t know what I’m going to do with you,’ sighed Charlie. ‘I’ve got to go to school on Monday, and I won’t be back till Friday. I have to sleep there, you know.’

Runner Bean jumped on to Charlie’s bed wagging his tail. He’d spent many happy hours in Charlie’s bedroom.

Charlie decided to ask his Uncle Paton for help. Slipping out of his room he crept along the landing until he came to his uncle’s door. A DO NOT DISTURB sign hung just above Charlie’s eye level. He knocked.

There was no reply.

Charlie cautiously opened the door and looked in. Paton wasn’t there. It was unlike him to leave the house in the morning. Charlie went over to a big desk covered with books and scraps of paper. On the tallest pile of books there was an envelope with Charlie’s name on it.

Charlie withdrew a sheet of paper from the envelope and read his uncle’s large scrawly handwriting.

Charlie, dear boy,

My sisters are up to no good. Heard them plotting in the small hours. Have decided to go and put a stop to things. If I don’t, someone very dangerous will arrive. No time to explain. Will be back in a few days – I hope!

Yours affectionately, Uncle P. P. S. Have taken wand.

‘Oh no,’ Charlie groaned. ‘When are things going to stop going wrong today?’

Unfortunately they had only just begun.

With a long sigh, Charlie left his uncle’s room, and walked straight into a pile of towels.

His other grandmother, Maisie Jones, who was carrying the towels, staggered backwards and then sat down with a bang.

‘Watch out, Charlie!’ she shouted.

Charlie pulled his rather overweight grandmother to her feet and, while he helped to gather up the towels, he told Maisie about Paton’s note and the problem of Runner Bean.

‘Don’t worry, Charlie,’ said Maisie. Her voice sank to a whisper as Grandma Bone came up the stairs. ‘I’ll look after the poor pooch. As for Uncle P– I’m sure it’ll all turn out for the best.’

Charlie went back to his room, dressed quickly and told Runner Bean that food would be coming, if not directly, then as soon as Grandma Bone went out. This could be any time of day, or not at all, but Runner Bean wasn’t bothered. He curled up on the bed and closed his eyes. Charlie went downstairs.

Maisie was filling the washing machine and Amy Bone, Charlie’s mother, was gulping down her second coffee. She told Charlie to have a good day, pecked him on the cheek and rushed off to the greengrocer’s where she worked. Charlie thought she looked rather too chic for a day weighing vegetables. Her golden brown hair was tied back with a velvet ribbon, and she was wearing a brand new corn-coloured coat. Charlie wondered if she’d got a boyfriend. He hoped not, for his vanished father’s sake.

Five minutes after his mother had left, Grandma Bone came downstairs in a black coat, her white hair now bundled up under a black hat. She told Charlie to brush his hair and then walked out with an odd smile on her pinched face.

As soon as she’d gone, Charlie ran to the fridge and pulled out a bowl of leftovers: last night’s lamb stew. Maisie grinned and shook her head, but she let Charlie take some of it to Runner Bean in a saucer. ‘That dog should be exercised before Grandma Bone comes back,’ she called.

Charlie took her advice. When Runner Bean had wolfed down the stew, Charlie took him out into the back garden, where they had a great game of hunt the slipper: a slipper that Charlie despised because it had his name embroidered in blue across the front.

Runner Bean was just chewing up the last bit of slipper, when Maisie flung open an upstairs window and called, ‘Look out, Charlie. The Yewbeams are coming!’

‘Stay here, Runner,’ Charlie commanded. ‘And be quiet, if you can.’

He leapt up the steps to the back door and ran to the kitchen, where he sat at the table and picked up a magazine. The aunts’ voices could be heard as they climbed the front steps. A key turned in the lock and then they were in the hall: Grandma Bone and her three sisters, all talking at once.

The great-aunts marched into the kitchen in new spring outfits. Lucretia and Eustacia had exchanged their usual black suits for charcoal grey but in Aunt Venetia’s case, it was purple. She also wore high-heeled purple shoes with golden tassels dangling from the laces. All three sisters had sinister smiles, and a threatening look in their dark eyes.

Aunt Lucretia said, ‘So here you are, Charlie!’ She was the eldest apart from Grandma Bone, and a matron at Charlie’s school.

‘Yes, here I am,’ said Charlie nervously.

‘Same hair, I see,’ said Aunt Eustacia, sitting opposite Charlie.

‘Yes, same hair,’ said Charlie. ‘Same hair for you too, I see.’

‘Don’t be cheeky.’ Eustacia patted her abundant grey hair. ‘Why haven’t you brushed it today?’

‘Haven’t had time,’ said Charlie.

He became aware that Grandma Bone was still talking to someone in the hall.

Aunt Venetia suddenly said, ‘Tah dah!’ and opened the kitchen door very wide, as if she were expecting the Queen or a famous film star to walk in. But it was Grandma Bone who appeared, followed by the prettiest girl Charlie had ever seen. She had golden curls, bright blue eyes and lips like a cherub.

‘Hello, Charlie!’ The girl held out her hand in the manner of someone expecting a kiss on the fingers, preferably from a boy on bended knees. ‘I’m Belle.’

Charlie was too flustered to do anything.

The girl smiled and sat beside him. ‘Oh my,’ she said. ‘A ladies’ magazine.’

Charlie realised, to his horror, that he was holding his mother’s magazine. On the cover a woman in pink underwear held a kitten. Charlie felt very hot. He knew his face must be bright red.

‘Make us some coffee, Charlie,’ Aunt Lucretia said sharply. ‘And then we’ll be off.’

Charlie flung down the magazine and ran to the coffee maker while Grandma Bone and the aunts sat babbling at him. Belle would be going to Charlie’s school, Bloor’s Academy, and Charlie must tell her all about it.

Charlie sighed. He wanted to visit his friend, Fidelio. Why did the aunts always have to spoil everything? For half an hour he listened to the chattering and giggling over the coffee and buns. Belle didn’t behave like a child, thought Charlie. She looked about twelve, but she seemed very comfortable with the aunts.

When the last drop had been squeezed out of the coffee pot, the three Yewbeam sisters left the house, blowing kisses to Belle.

‘Take care of her, Charlie,’ Aunt Venetia called.

Charlie wondered how he was supposed to do that.

‘Can I wash my hands, Grizel – er – Mrs Bone?’ Belle held up her sticky fingers.

‘There’s the sink,’ Charlie nodded to the kitchen sink.

‘Upstairs, dear,’ said Grandma Bone, with a scowl in Charlie’s direction. ‘Bathroom’s first left. There’s some nice lavender soap and a clean towel.’

‘Thank you!’ Belle skipped out.

Charlie gaped. ‘What’s wrong with the kitchen?’ he asked his grandmother.

‘Belle has tender skin,’ said Grandma Bone. ‘She can’t use kitchen soap. I want you to lay the dining room table – for five. I presume Maisie will be joining us.’

‘The dining room?’ said Charlie in disbelief. ‘We only eat there on special occasions.’

‘It’s for Belle,’ snapped Grandma Bone.

‘A child?’ Charlie was amazed.

‘Belle is not just any child.’

So it seems, thought Charlie. He went to lay the dining room table while Grandma Bone shouted instructions up to Maisie. ‘We’d like a nice light soup today, Maisie. And then some cold ham and salad. Followed by your lovely Bakewell tart.’

‘Would we indeed, your highness?’ Maisie shouted from somewhere upstairs. ‘Well, we’ll have to wait, I’m afraid. Oops! Who on earth are you?’

She had obviously bumped into Belle.

Charlie closed the dining room door and went to the window. There was no sign of Runner Bean in the garden. Charlie had visions of a dog’s lifeless body lying in a gutter. He ran to the back door, but just as he was about to open it, a sing-song voice called, ‘Charleee!’

Belle was standing in the hall, staring at him. Charlie could have sworn that her eyes had been blue. Now they were green.

‘Where are you going, Charlie?’ she asked.

‘Oh, I was just going into the garden for a . . .a . . .’

‘Can I come with you?’

‘No. That is, I’ve changed my mind.’

‘Good. Come and talk to me.’

Was it possible? Belle’s eyes were now a greyish brown. Charlie followed her into the sitting room where she sat on the sofa, patting a cushion beside her. Charlie perched at the other end.

‘Now, tell me all about Bloor’s.’ Belle smiled invitingly.

Charlie cleared his throat. Where should he begin? ‘Well, there are three sort of departments, Music, Art and Drama. I’m in Music so I have to wear a blue cape.’

‘I shall be in Art.’

‘Then you’ll wear green.’ Charlie glanced at the girl. ‘Haven’t my aunts told you all this? I mean, are you staying with them, or what?’

‘I want to hear it from you,’ said Belle, ignoring Charlie’s question.

Charlie continued. ‘Bloor’s is a big grey building on the other side of the city. It’s very, very old. There are three cloakrooms, three assembly halls and three canteens. You go up some steps between two towers, cross a courtyard, up more steps and into the main hall. You have to be silent in the hall or you’ll get detention. The Music students go through a door under crossed trumpets, your door is under the sign of a pencil and paintbrush.’

‘What’s the sign for the Drama students?’

‘Two masks. One sad and one happy.’ Why did Charlie get the impression that Belle knew all this? Her eyes were blue again. It was unnerving.

‘There’s another thing,’ he said. ‘Are you – er – like me; one of the children of the Red King? I mean, was he your ancestor too?’

Belle turned her bright blue gaze on him. ‘Oh, yes. And I’m endowed. But I prefer not to say how. I’m told that you can hear voices from photographs, and even paintings.’

‘Yes.’ Charlie could do more than hear voices, but he wasn’t going to give anything away to this strange girl. ‘Endowed children have to do their homework in the King’s room,’ he said. ‘There are twelve of us. Someone from Art will show you where it is: Emma Tolly. She’s a friend of mine, and she’s endowed too.’

‘Emma? Ah, I’ve heard all about her.’ Belle inched her way up the sofa towards Charlie. ‘Now, tell me about you, Charlie. I believe that your father’s dead.’

‘He’s not!’ said Charlie fiercely. ‘His car went into a quarry, but they never found his body. He’s just – lost.’

‘Really? How did you find that out?’

Without thinking, Charlie said, ‘My friend Gabriel’s got an amazing gift. He can feel the truth in old clothes. I gave him my father’s tie and Gabriel said that he wasn’t dead.’

‘Well, well.’ The girl gave Charlie a sweet, understanding smile, but the effect was spoiled by the cold look in her eyes – now a dark grey. And, was it a trick of the light, or did he glimpse a set of wrinkles just above her curved pink lips?

Charlie slipped off the sofa. ‘I’d better help my other gran with lunch,’ he said.

He found Maisie in the kitchen, throwing herbs into a saucepan. ‘All this fuss for a child,’ she muttered. ‘I’ve never heard of such a thing.’

‘Nor me,’ said Charlie. ‘She’s a bit strange, isn’t she?’

‘She’s downright peculiar. Belle indeed!’

‘Belle means beautiful,’ said Charlie, remembering his French. ‘And she is very pretty.’

‘Huh!’ said Maisie.

When the soup was ready Charlie helped Maisie to carry it into the chilly dining room. Grandma Bone was already sitting at the head of the table, with Belle on her right.

‘Where’s Paton?’ asked Grandma Bone.

‘He won’t be coming,’ said Charlie.

‘And why not?’

‘He doesn’t eat with us, does he?’ Charlie reminded her.

‘Today, I want him here,’ said Grandma Bone.

‘Well, you won’t get him,’ said Maisie. ‘He’s gone away.’

‘Oh?’ Grandma Bone stiffened. ‘And how d’you know that?’ She glared, first at Maisie and then Charlie.

Maisie looked at Charlie.

Charlie said, ‘He left a note.’

‘And what did it say?’ demanded Grandma Bone.

‘I can’t remember all of it,’ Charlie mumbled.

‘Let me see it!’ She held out a bony hand.

‘I tore it up,’ said Charlie.

Grandma Bone’s eyebrows plummeted in a dark scowl. ‘You shouldn’t have done that. I want to know what’s going on. I must know what my brother said.’

‘He said he’d gone to see my great-grandpa, your father, although you never go to see him.’

His grandmother’s tiny black eyes almost disappeared into their wrinkled sockets. ‘That’s none of your business. Paton visited our father last week. He only goes once a month.’

Charlie only just stopped himself from mentioning his own visit to his great-grandfather. Because of the family feud it had to remain a secret. But Uncle Paton had never told him what caused the feud or why he mustn’t talk about it. He’d have to tell another lie. ‘It was an emergency.’

This seemed to satisfy Grandma Bone, but Belle continued to stare at Charlie. Her eyes were now dark green and a chilling thought occurred to him. Uncle Paton had gone to stop someone dangerous from arriving. But perhaps that person was already here?

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.