Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

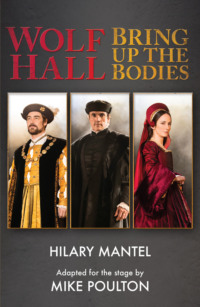

Buch lesen: "Wolf Hall & Bring Up the Bodies: RSC Stage Adaptation - Revised Edition"

WOLF HALL

and BRING UP THE BODIES

Adapted for the stage by

Mike Poulton

From the novels by

Hilary Mantel

With an introduction by Mike Poultonand character notes by Hilary Mantel

NICK HERN BOOKS

HarperCollinsPublishers

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk www.4thestate.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Original Production

Introduction by Mike Poulton

Notes on Characters by Hilary Mantel

Characters

Dedication

Wolf Hall

Bring Up the Bodies

About the Authors

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

These adaptations of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies were originally commissioned by Playful Productions and were first produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, on 11 December 2013. The productions transferred to the Aldwych Theatre, London, on 1 May 2014, presented by Matthew Byam Shaw, Nia Janis and Nick Salmon for Playful Productions and the Royal Shakespeare Company, Bartner/Tulchin Productions and Georgia Gatti for Playful Productions. The cast was as follows:

| MARK SMEATON | Joey Batey |

| CHARLES BRANDON, DUKE OF SUFFOLK | Nicholas Boulton |

| KATHERINE OF ARAGON/JANE BOLEYN, LADY ROCHFORD | Lucy Briers |

| JANE SEYMOUR/PRINCESS MARY/LADY WORCESTER | Leah Brotherhead |

| MARY BOLEYN/LIZZIE WYKYS/MARY SHELTON | Olivia Darnley |

| THOMAS HOWARD, DUKE OF NORFOLK | Nicholas Day |

| ENSEMBLE | Mathew Foster |

| GREGORY CROMWELL | Daniel Fraser |

| BARGE MASTER/WOLSEY’S SERVANT | Benedict Hastings |

| LADY IN WAITING/MAID/MARJORIE SEYMOUR | Madeleine Hyland |

| CARDINAL WOLSEY/SIR JOHN SEYMOUR/SIR WILLIAM KINGSTON/ARCHBISHOP WARHAM | Paul Jesson |

| ANNE BOLEYN | Lydia Leonard |

| ENSEMBLE | Robert MacPherson |

| THOMAS CROMWELL | Ben Miles |

| CHRISTOPHE/FRANCIS WESTON | Pierro Niél Mee |

| KING HENRY VIII | Nathaniel Parker |

| GEORGE BOLEYN, LORD ROCHFORD/EDWARD SEYMOUR | Oscar Pearce |

| STEPHEN GARDINER/EUSTACHE CHAPUYS | Matthew Pidgeon |

| THOMAS MORE/HENRY NORRIS | John Ramm |

| HARRY PERCY/WILLIAM BRERETON | Nicholas Shaw |

| RAFE SADLER | Joshua Silver |

| THOMAS CRANMER/THOMAS BOLEYN/PACKINGTON/FRENCH AMBASSADOR | Giles Taylor |

| THOMAS WYATT/HEADSMAN | Jay Taylor |

| MUSICIANS | Rob Millett,Greg Knowles,Adam CrossDario Rossetti-BonellCatherine Groom |

| All other parts played by members of the company. | |

| Director | Jeremy Herrin |

| Designer | Christopher Oram |

| Season Lighting Designer | Paule Constable |

| Wolf Hall Lighting Designer | Paule Constable |

| Bring Up the Bodies Lighting Designer | David Plater |

| Music | Stephen Warbeck |

| Sound Designer | Nick Powell |

| Movement Director | Siân Williams |

| Fight Director | Bret Yount |

Adapting Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies

Mike Poulton

Over three years ago I was asked if it might be possible to adapt Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall for the stage. At the time of asking, Bring Up the Bodies did not exist. I’d read Wolf Hall and been gripped by it – from the first page to the last – page 653. It’s an extraordinary read. To call it a historical novel diminishes it – for me it’s a deeply serious piece of literature that happens to be set in and around the Court of Henry VIII. I can think of no other contemporary work of period fiction that comes near it. It’s that rare thing – a novel that richly deserved its fame and the accolades and prizes heaped upon it. I knew that Hilary was at work on a sequel and I was counting the days. I read Wolf Hall again. I said that I thought it could be made into a play if the right adapter could be found. ‘Might you be the right adapter?’ I was asked.

I had never worked with a living author. Earlier collaborators, Schiller, Chekhov, Turgenev, Chaucer, Malory, were all long dead. Hilary is very much alive, and I knew that for the project to work she and I would have to get on together, and agree about how best to engineer the transformation. I imagined it would be like taking apart a Rolls-Royce and reassembling the parts as a light aircraft. After three years together I can say that our collaboration has proved to be, for me at any rate, the most rewarding part of the experience. I have learned so much. Hilary has been generous and committed in every way with advice, with time, with invention, with challenges – all coming out of a deep knowledge of her subject, and easy familiarity with the complex minds of the characters she has created. Fortunately, she also has a love and instinctive understanding of the workings of theatre. Above all it’s been fun – a lot of fun. Her attitude from the first was that she had brought Cromwell and company to life, and I was free, within the limits of the story and the requirements of historical accuracy, to move them about on the stage as I saw fit. Though on many occasions she has had to pull me out of holes into which I’ve dug myself. I’ve never had that sort of help from Friedrich von Schiller.

So what were the problems we faced at the outset? I felt that, in terms of staging – in order to create a workable dramatic framework – we had to get to the death of Anne Boleyn. If we could do that, we’d have a strong tragic arc – the ascendancy of Anne followed by her rapid decline. If Thomas Cromwell’s rise from obscurity was to be the story of the play, the Court of Henry VIII must be the stage upon which he acts, and the rise and fall of Anne Boleyn the engine that drives the action. I knew Hilary was working on a sequel to Wolf Hall, to be called The Mirror and the Light. Could she take me as far as Anne’s execution? Yes, of course she could. But by the time she reached the summer of 1536 we had another book, Bring Up the Bodies, and so much tempting new material that the original play was rapidly becoming two plays. Since that time the only heartbreak in the process has been deciding what to set aside.

Structurally, the new material was exactly what was needed. Wolf Hall would take us to Anne’s coronation, and Bring Up the Bodies to her execution. But the growing scale of the project and size of the cast meant that we needed a new partner and a new home. The Royal Shakespeare Company, under its brightly shining, new-minted Artistic Director, Gregory Doran, welcomed us in. This was a turning point. I’d worked five times with Greg, and I knew that from the RSC we’d get the expertise, support and resources the plays needed and deserved. We have not been disappointed.

It might be thought that the sheer length of the two books would present problems. I never thought so. The way a novel is structured cannot be reproduced on the stage – there could be no question of simply putting two whole novels on their feet. They had to be completely re-imagined as plays. The immediate questions were what would be lost, and what, if anything, would be gained in the stage versions? We set out to convert our difficulties into opportunities.

The content of the books cannot be condensed. You can’t repaint the jewel-like miniature scenes of the original with broad brushstrokes. You can’t ask an actor to play a summary of events – actors need detail. Adaptation is the process of choosing vital and dramatic details from the novels and relaying them like stepping stones along a clear route from a beginning, through a middle, and then in a headlong rush to the end. Pace is everything. To falter on stepping stones is to end up in the river.

Losses and gains? Strong characters are the life of Hilary’s books. So in terms of character, nothing could be changed. I wanted Cromwell, Wolsey, Anne and Henry – and all the other powerful characters we’ve included – to leap alive and fully formed from the pages of the books onto the stage of the Swan. If this could be accomplished, I felt the spirit of the book would remain intact. Incident has been lost. Obviously, we can’t reproduce every scene and every conversation we read in the original work, so we’ve had to be highly selective. There’s no doubt that readers will have favourite scenes that are not shown in the plays. But the story should gain a different sort of pace and drive in the playing. In the novels it’s as if we’re standing at Cromwell’s shoulder observing what he observes and sharing his thoughts. Seeing events through Cromwell’s eyes was the prime requirement of the adaptation. Sometimes what works perfectly in a novel won’t read in a live performance. Some of the most memorable images in the books are formed in Cromwell’s head: his reflections, his plotting, his private anguish, and, most of all, his barely contained laughter. Cromwell is very often on the point of dissolving into mirth. We decided at an early stage not to indulge in ‘pieces to camera’ – monologues delivered chorus-like by Cromwell to the audience. So in working with RSC actors through the drafts – there have been nine – we decided to give Cromwell two confidants, one from his household, one from Court, with whom he can share his thoughts: Rafe Sadler and Thomas Wyatt. And we have also provided him with a few completely new scenes which have no equivalent in the books.

Once the characters were comfortable, and sure-footed, on stage, it became possible to give them their heads in order to drive the plotting forward. There are many fewer characters in the plays than in the novels – a cast of one hundred and thirty would overcrowd the intimate playing space of the Swan – but other characters have risen to prominence and have been given more to do in the telling of the story. Christophe, for example, in some ways a model of Cromwell’s younger self, seems to be everywhere, and is usually up to mischief.

Our choice of theatre – the Swan is always my first choice – suggested, or rather insisted upon, a particular tone and style for our two plays. It’s a small space with a deep thrust stage. Wherever you sit, you feel you’re part of the action. Instead of looking over Cromwell’s shoulder, as in the books, throughout the plays you’re on stage with him. And he is on stage all the time. There’s spectacle – masques at Court, dances, courts of inquiry, even a coronation and a deer hunt. There’s detail – quiet scenes at home in Austin Friars, a fire in the Queen’s chambers in the middle of the night, scenes of intrigue and interrogation, and ghostly visitations. But there are no elaborate stage tricks – no revolves, lifts, nor clever-clever scene changes – everything has to be accomplished by the actors. They have their voices, their costumes, music, lighting, props, and an infinitely flexible playing space that can carry us in seconds from King Henry’s bedchamber, where he huddles for warmth over a fire, to a cold night on a boat in the middle of the River Thames. The Swan is the perfect theatre for storytelling. I’d previously worked through the twenty and more stories of The Canterbury Tales there, and there were valuable lessons to be learned from that experience. As I re-read Wolf Hall, and later Bring Up the Bodies, many more times, I tried to gear scenes to what I knew would work well in the Swan. And I knew – from touring Canterbury Tales – that if a play works in the Swan, it will play well in other theatres.

In bringing these two great novels to the stage, I have tried to replace the private pleasure of reading with the communal excitement of live theatre. When you read Wolf Hall, Cromwell and company get inside your head – they look as much through your eyes as you look through theirs. When you watch Wolf Hall, I hope we’re offering you a completely different experience – it should be like stepping into the world of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies – being rowed down the Thames with a dejected Wolsey, sitting at dinner with the King, chasing rats with Christophe, being in the Tower with Thomas More, or waiting to take a turn at swinging the headsman’s sword.

Notes on Characters

Hilary Mantel

Thomas Cromwell

Elizabeth Cromwell

Cardinal Archbishop Thomas Wolsey

King Henry VIII

Anne Boleyn

Katherine of Aragon

Princess Mary

Stephen Gardiner

William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury

Thomas Cranmer, Incoming Archbishop of Canterbury

Thomas More

Rafe Sadler

Harry Percy

Christophe

Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

Eustache Chapuys

Sir Henry Norris

Sir William Brereton

Mark Smeaton

George Boleyn, Lord Rochford

Francis Weston

Sir Thomas Boleyn

Thomas Wyatt

Gregory Cromwell

Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford

Mary Boleyn

Elizabeth, Lady Worcester

Mary Shelton

Sir John Seymour

Jane Seymour

Edward Seymour

Sir William Kingston, Constable of the Tower

The Calais Executioner

THOMAS CROMWELL

You are the man with the slow resting heartbeat, the calmest person in any room, the best man in a crisis. You are a robust, confident, centred man, and your confidence comes from the power you have in reserve: your Putney self, ready to be unleashed, like an invisible pit bull. No one knows where you have been, or who you know, or what you can do, and these areas of mystery, on which you cast no light, are the source of your power. When you are angry, which is rare, you are terrifying.

Your date of birth is unknown (nobody noticed) but you are in your forties during the action of these plays and about fifty at the time of Anne Boleyn’s fall. Your father was a blacksmith and brewer, the neighbour from Hell to the townsfolk of Putney, a heavy drinker and prone to violence. Your mother’s name is unknown. You don’t say much about your past, but you tell Thomas Cranmer, ‘I was a ruffian in my youth.’ Whatever this statement reveals or conceals, you have a lifelong sympathy with young men who have veered off-course.

At about the age of fifteen you vanish abroad. You join the French Army and speak French. You go into the household of a Florentine banker and speak Italian. You set up in the wool trade in Antwerp and speak Flemish and also Spanish, the language of the occupying power. You come home to London: and who are you? You’re a man who speaks the language of the occupying power. Traces of the blacksmith’s boy are almost invisible. The rough diamond is polished. You have seen at least one battle at close quarters, a calamitous defeat for your side; it’s enough to turn you against war. You have seen childhood poverty and modest prosperity and you know all about what money can buy. You have learned from every situation you have been in. You are flexible, pragmatic and shrewd, with a streak of sardonic humour. You are widely read, understand poetry and art. Somewhere on the road you found God. Your exact views (like much about you) remain unknown. But you are a reformer and your religious feelings are strong and genuine.

On the other hand… you’re quite prepared to torture someone, if reasons of State demand it and the King agrees. (You probably don’t torture Mark Smeaton.) You are a natural arbitrator and negotiator, preferring a settlement to a fight, but if pushed – as you are by the Boleyns in 1536 – you are ingenious and ruthless.

You marry Elizabeth Wykys, a prosperous widow with connection in the wool trade. You have three children. You take up the law and go to work for Cardinal Wolsey, looking after his business affairs. You help him raise the funds for Cardinal College (which is now Christchurch) by closing or amalgamating a group of small monasteries, work which equips you for the mighty programme of Church reorganisation you will soon undertake for Henry.

You and Wolsey are close. When he falls from favour, you are the only person who remains completely loyal. Much about you is equivocal, but this is not. You get yourself a seat in the Commons, and through his long winter in exile at Esher you attend every sitting, trying to talk out the charges that have been brought against him. You expend effort and your own money. When he goes north, you remain in London looking after his interests. You warn him that the way to survive is to retire into private life. But, though he listens to you on most matters, in this instance he doesn’t. His loss is devastating to you. Ten years later, you are still defending his good name: though Wolsey, a corrupt papist, ought to have been everything you hate.

You first come to Henry’s notice when Wolsey’s empire has to be pulled apart. Henry does not think he has many true friends and is touched by your loyalty to the Cardinal. You become his unofficial adviser long before you are sworn in to the Council. Your promotion causes predictable outrage, not just because of your humble background but because you are still known as the Cardinal’s man. To save everyone embarrassment, it is proposed you adopt a coat of arms from another, more respectable family called Cromwell. But you refuse. You are not ashamed of your background; you don’t talk about it, but you don’t conceal it either. In fact, you never apologise, and never explain. (And when you get your own coat of arms, you incorporate a motif from Wolsey’s arms, so that it flies in the faces of his old enemies for years to come.)

When your wife (and two little daughters) die, you do not marry again. This, for the time, is unusual. We don’t know your reasons. You have women friends; this is not understood, for example, by the Duke of Norfolk, who tells you that he never had a conversation with his own daughter until she was about twenty years of age, and was perplexed to find that she had ‘a good wit.’

Your household at Austin Friars, as you progress in the King’s service, is transformed, extended, rebuilt, into a great ministerial household, a power centre, cosmopolitan and full of young men who are there to gain promotion. You take on the people written off elsewhere, the wild boys who are on everybody’s wrong side, and make them into useful workers. You are an administrative genius, able to plan and accomplish in weeks what would take other people years. You are good at delegating and your instructions are so precise that it’s difficult to make a mistake. You extend the secretary’s role so that it covers most of the business of State; you know what happens in every department of Government. Your ideas are startlingly radical, but mostly they are beaten off by a conservative Parliament. At the centre of a vast network of patronage, you have a steady tendency to grow rich. You are generous with your money, a patron of artists, writers and scholars, and of your own troupe of actors, ‘Lord Cromwell’s Men’. The kitchen at Austin Friars feeds two hundred poor Londoners daily. All the same, you are a focus of resentment. The aristocracy don’t like you on principle, and the ordinary people don’t like you either. In the opinion of the era, there’s something unnatural about what you’ve achieved. In the north they think you’re a sorcerer.

Much of your myth is ill-founded. You do not control a vast spy network. You do not throw elderly monks into the road; in fact, you give them pensions. You are not the dour man of Holbein’s portrait but (witnesses say) lively, witty and eloquent. You have a remarkable memory, and are credited with knowing the entire New Testament by heart. Your particular distinction is this: you are a big-picture man who also sees and takes care of every detail.

Apart from your intellectual ability, your greatest asset is that you manage to get on with the most unlikely people. You are affable, gregarious, and amazingly plausible. You easily convince people you are on their side, when common sense should suggest different. You tie people to you by favours rather than by fear, and so they don’t easily see what a grip you’ve taken. People open their hearts to you. They tell you all sorts of things. But you tell them nothing.

What do you really think of Henry? No one knows. You don’t seem to feel the warmth towards him that Wolsey did, but you respect his abilities and you serve him because he is the focus of good order and keeps the country together. Dealing with him on a day-to-day basis needs tact and patience. You are optimistic and resilient, and believe there’s hope even for the bigoted and the terminally stubborn. Those who are on the inside track with you have their interests protected, and you take trouble to help out those in difficulties. But those who cross you are likely to find that you have been out by night and silently dug a deep pit beneath their career plans.

Your weakness is that you do not head up a faction or an interest group and have no power base of your own; you depend completely on the King’s favour. You are resented by the old nobility, and you are destroyed when your two implacable enemies, Norfolk and Gardiner, manage to make common cause. But by then, you have reshaped England, and even the reign of the furiously papist Mary can’t undo your work; you have given too many people a stake in your remodelled society.

ELIZABETH CROMWELL

You were the daughter of Henry Wykys, a prosperous wool trader, and were first married to Thomas Williams, a yeoman of the guard, and then to Cromwell. Your family were connected to Putney and may have been Welsh in origin. You have three children, Gregory, Anne and Grace. You die in one of the epidemics of ‘sweating sickness’ that sweep the country in the late 1520s, and your daughters follow you. You are a member of a close family and your sister, mother and brother-in-law continue to live at Austin Friars for many years.

We know nothing about you, so we can only say, ‘women like you’. City wives were usually literate, numerate and businesslike, used to managing a household and a family business in cooperation with their husbands. In Wolf Hall I make you a ‘silk woman’, with your own business, like the wife of Cromwell’s friend Stephen Vaughan, who supplied Anne Boleyn’s household with small but valuable articles made of silk braid: cauls for the hair, ties for garments. Cromwell watches you weave one of these braids, fingers moving so fast that he can’t follow the action. He asks you to slow down and show him how it’s done. You say that if you slowed down and stopped to think you wouldn’t be able to do it. He remembers this when he is deep into the coup against Anne Boleyn.

CARDINAL ARCHBISHOP THOMAS WOLSEY

You are, arguably, Europe’s greatest statesman and greatest fraud. You are also a kind man, tolerant and patient in an age when these qualities are not necessarily thought virtues.

You are not quite the enormous scarlet cardinal of the (posthumous) portrait. You are more splendid than stout, a man of iron constitution who has survived the ‘sweating sickness’ six times. You are a cultured Renaissance prince, as grand and worldly as any Italian cardinal. Renowned for the speed at which you travel, you are capable of an unbroken twelve-hour stint at your desk, ‘all which season my lord never rose once to piss, nor yet to eat any meat, but continually wrote his letters with his own hands…’ Your household observes you with awe, as does the known world. You hope you might be Pope one day, but think it would be more convenient if you could bring the papacy to Whitehall; you wouldn’t want to give up your palaces or your place next to your own monarch, and anyway you could probably run Christendom in your spare time.

You are the son of a prosperous butcher and grazier, and your family seem to have known how extraordinary you were, because they sent you to Oxford, where you took your first degree at fifteen and where you were known as ‘the boy bachelor’. The Church is the route to advancement for the poor boy. And your route is paved with gold. You acquire influential patrons and enter the service of Henry VII.

When Henry VIII came to the throne you were ready to take much of the burden off the young back, and the Prince was glad to let you carry it. You have real esteem and affection for the young Henry, and he loves you for your personal warmth as well as your unique abilities. You are not only Lord Chancellor but the Pope’s permanent legate in England. So your concentration of power, foreign and domestic, lay and clerical, is probably greater than that wielded by any individual in English history, kings and queens excepted. You are more than the King’s minister, you are the ‘alternative king’, ostentatious and very rich; suave, authoritative, calm; an ironist, worldly-wise, unencumbered by too much ideology. You never simply walk, you process: your life is a spectacle, a huge performance mounted for the benefit of courtiers and kings. You are acting, particularly, when you’re angry: after the performance, you shrug and laugh.

Until the point where this story starts, you have been able to solve almost every problem that’s faced you. You are so sure of yourself, that your unravelling is total and unexpected and tragic.

When Henry first asks for an annulment of his marriage, you are confident that you will be able to secure it. But the politics of Europe turn against you, and you find yourself trapped, faced with an impatient, angry monarch, and between two women who hate you: Katherine of Aragon, who has always been jealous of your influence with the King, and Anne Boleyn, who resents you because, before the King set his heart on her, you frustrated the good marriage she intended to make. You are astonished by the extent of the enmity you have aroused (or at least, you say you are) and, like everyone else, you are baffled by the King’s conduct; he wants you banished, then he offers to make peace, then he wants you banished.

For a year your enemies at Court are nervous that the King will reinstate you. No one is capable of assuming your role in Government, and Henry quickly learns this. When you are packed off to the north of England, you do not behave like a man in disgrace. You draw both the gentry and the ordinary people into your orbit, and soon you are living like a great prince again, and writing to the powers of Europe to ask them to help you regain your status. When these letters are intercepted, you are arrested and set out to London to face treason charges.

Soon after your arrest you have what sounds like a heart attack, followed by an intestinal crisis which leads to catastrophic bleeding. There are rumours that you have poisoned yourself. You are forced to continue the journey, and die at Leicester Abbey. Your body is shown to the town worthies so that no one can claim that you have survived and escaped, to set up opposition to Henry in Europe. It is the kind of precaution usually taken for a prince. Even dead, you spook your opponents. Your tomb – which you have been designing for twenty years, with the help of Florentine artists – is taken apart bit by bit and elements find their way all over Europe. At St Paul’s, Lord Nelson occupies your marble sarcophagus, rattling around like a dried pea.

KING HENRY VIII

Let’s think of you astrologically, because your contemporaries did. You are a native of Cancer the Crab and so never walk a straight line. You go sideways to your target, but when you have reached it your claws take a grip. You are both callous and vulnerable, hard-shelled and inwardly soft.

You are a charmer and you have been charming people since you were a baby, long before anyone knew you were going to be King. You were less than four years old when your father showed you off to the Londoners, perched alone on the saddle of a warhorse as you paraded through the streets.

Even as a child you behaved more like a king than your elder brother did. Arthur was dutiful and reserved, always with your father, whereas you were left with the women, a bonny, boisterous child, able to command attention. You were only ten when your brother married the Spanish Princess Katherine, but when you danced at the wedding, all eyes were on you.

At Arthur’s sudden death, your mother and father are plunged into deep grief and dynastic panic. It’s by no means sure that, were your father also to die now, you would come to the throne as the second Tudor; no one wants rule by a child. But your father battles on for a few more years, and you step into Arthur’s role gladly, an understudy who will play the part much better than the original cast member. Later, do you feel some guilt about this?

You are eighteen when you become King, a ‘virtuous prince’, seemingly a model for kingship; you are intellectually gifted, pious, a linguist, a brilliant sportsman, able to write a love song or compose a mass. Almost at once, you marry your brother’s widow and you execute your father’s closest advisers. The latter action is a naked bid for popularity, and it ought to give warning of the seriousness of your intent. Still, early in your reign you put more effort into hunting and jousting than to governing, with a bit of light warfare thrown in. You prefer to look like a king than be a king, which is why you let Thomas Wolsey run the country for you.

You are sexually inexperienced and will always be sexually shy; you don’t like dirty jokes. You have a few liaisons, but they are low-key and discreet. You never embarrass Katherine, who is too grand to display any jealousy, though she is too much in love with you not to care. However, you cosset and promote your illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy (a son you can acknowledge, as his mother was unmarried). Fitzroy has his own household, so is not part of the daily life of the Court, but is loaded with honours.

You are approaching forty when this story starts, five years younger than Thomas Cromwell. You are not ageing particularly well; still trim, still good-looking, you remain a superb athlete and jouster, but in an effort to hang on to your youth you have taken to collecting friends who are a generation younger than you, lively young courtiers like Francis Weston.

Your manner is relaxed, rather than domineering. You are highly intelligent, quick to grasp the possibilities of any situation. You expect to get your own way, not just because you are a king but because you are that sort of man. When you are thwarted, your charm vanishes. You are capable of a carpet-chewing rage, which throws people because it is so unexpected, and because you will turn on the people closest to you. But most of the time you like to be liked; you have no fear of confronting men, though you don’t seek confrontation, but you will not confront a woman, so you are run ragged between Katherine and Anne, trying to placate one and please the other. Unlike most men of your era, you truly believe in romantic love (though, of course, not in monogamy). It is an ideal for you. You were in love with Katherine when you married her and when you fall in love with Anne Boleyn you feel you must shape your life around her. Likewise, when Jane Seymour comes along…

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.