Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

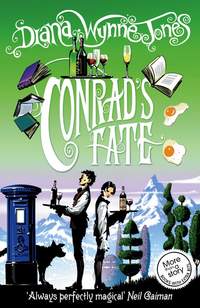

Buch lesen: "Conrad’s Fate"

Diana Wynne Jones

CONRAD’S FATE

Illustrated by Tim Stevens

Dedication

To Stella Paskins

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Author’s Preface

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher

Author’s Preface

This book, and all the other books about Chrestomanci, takes place in a universe made up of many worlds. People living in these worlds have explored them and given them the name “Related Series” on the grounds that the same languages are spoken in each. There are twelve such Series, numbered One to Twelve, and there are usually nine different worlds in each Series, each of which will share the same geography as others of the same number. (For instance, Series Two is a mass of marshy land and rivers, Series Five is all islands, and Series Seven has the worlds where the British Isles have not split off from the continent of Europe).

Chrestomanci himself lives in Series Twelve A, which is like our own world except that magic is common there. Our own world is Twelve B and does not have magic to speak of. A magic user using the proper spells can easily cross from one world to another, which is what Christopher does in this book.

Conrad’s Fate takes place in Series Seven and, although there are in fact thousands of different worlds, none of the others need concern you here.

Diana Wynne Jones

Chapter One

When I was small, I always thought Stallery Mansion was some kind of fairy-tale castle. I could see it from my bedroom window, high in the mountains above Stallchester, flashing with glass and gold when the sun struck it. When I got to the place at last, it wasn’t exactly like a fairy tale.

Stallchester, where we had our shop, is quite high in the mountains too. There are a lot of mountains here in Series Seven and Stallchester is in the English Alps. Most people thought this was the reason why you could only receive television at one end of the town, but my uncle told me it was Stallery doing it.

“It’s the protections they put round the place to stop anyone investigating them,” he said. “The magic blanks out the signal.”

My Uncle Alfred was a magician in his spare time so he knew this sort of thing. Most of the time he made a living for us all by keeping the bookshop at the cathedral end of town. He was a skinny, worrity little man with a bald patch under his curls and he was my mother’s half-brother. It always seemed a great burden to him, having to look after me and my mother and my sister Anthea. He rushed about muttering, “And how do I find the money, Conrad, with the book trade so slow!”

The bookshop was in our name too – it said GRANT AND TESDINIC in faded gold letters over the bow windows and the dark green door – but Uncle Alfred explained that it belonged to him now. He and my father had started the shop together. Then, just after I was born and a little before he died, my father had needed a lot of money suddenly, Uncle Alfred told me, and he sold his half of the bookshop to Uncle Alfred. Then my father died and Uncle Alfred had to support us.

“And so he should do,” my mother said in her vague way. “We’re the only family he’s got.”

My sister Anthea said she wanted to know what my father had needed the money for, but she never could find out. Uncle Alfred said he didn’t know. “And you never get any sense out of Mother,” Anthea said to me. “She just says things like ‘Life is always a lottery’ and ‘Your father was usually hard up’ – so all I can think is that it must have been gambling debts. The casino’s only just up the road after all.”

I rather liked the idea of my father gambling half a bookshop away. I used to like taking risks myself. When I was eight I borrowed some skis and went down all the steepest and iciest ski runs, and in the summer I went rock climbing. I felt I was really following in my father’s footsteps. Unfortunately, someone saw me halfway up Stall Crag and told my uncle.

“Ah, no, Conrad,” he said, wagging a worried, wrinkled finger at me. “I can’t have you taking these risks.”

“My dad did,” I said, “betting all that money.”

“He lost it,” said my uncle, “and that’s a different matter. I never knew much about his affairs, but I have an idea – a very shrewd idea – that he was robbed by those crooked aristocrats up at Stallery.”

“What?” I said. “You mean Count Rudolf came with a gun and held him up?”

My uncle laughed and rubbed my head. “Nothing so dramatic, Con. They do things quietly and mannerly up at Stallery. They pull the possibilities like gentlemen.”

“How do you mean?” I said.

“I’ll explain when you’re old enough to understand the magic of high finance,” my uncle replied. “Meanwhile…” His face went all withered and serious. “Meanwhile, you can’t afford to go risking your neck on Stall Crag, you really can’t, Con, not with the bad karma you carry.”

“What’s karma?” I asked.

“That’s another thing I’ll explain when you’re older,” my uncle said. “Just don’t let me catch you going rock climbing again, that’s all.”

I sighed. Karma was obviously something very heavy, I thought, if it stopped you climbing rocks. I went to ask my sister Anthea about it. Anthea is nearly ten years older than me and she was very learned even then. She was sitting over a line of open books on the kitchen table, with her long black hair trailing over the page she was writing notes on. “Don’t bother me now, Con,” she said without looking up.

She’s growing up just like Mum! I thought. “But I need to know what karma is.”

“Karma?” Anthea looked up. She has huge dark eyes. She opened them wide to stare at me, wonderingly. “Karma’s sort of like Fate, except it’s to do with what you did in a former life. Suppose that in a life you had before this one you did something bad, or didn’t do something good, then Fate is supposed to catch up with you in this life, unless you put it right by being extra good of course. Understand?”

“Yes,” I said, though I didn’t really. “Do people live more than once then?”

“The magicians say you do,” Anthea answered. “I’m not sure I believe it myself. I mean, how can you check that you had a life before this one? Where did you hear about karma?”

Not wanting to tell her about Stall Crag, I said vaguely, “Oh, I read it somewhere. And what’s pulling the possibilities? That’s another thing I read.”

“It’s something that would take ages to explain and I haven’t time,” Anthea said, bending over her notes again. “You don’t seem to understand that I’m working for an exam that could change my entire life!”

“When are you going to get lunch then?” I asked.

“Isn’t that just my life in a nutshell!” Anthea burst out. “I do all the work round here and help in the shop twice a week, and nobody even considers that I might want to do something different! Go away!”

You didn’t mess with Anthea when she got this fierce. I went away and tried to ask Mum instead. I might have known that would be no good.

Mum has this little bare room with creaking floorboards half a floor down from my bedroom, with nothing in it much except dust and stacks of paper. She sits there at a wobbly table, hammering away at her old typewriter, writing books and magazine articles about Women’s Rights. Uncle Alfred had all sorts of smooth new computers down in the back room where Miss Silex works, and he was always on at Mum to change to one as well. But nothing will persuade Mum to change. She says her old machine is much more reliable. This is true. The shop computers went down at least once a week – this, Uncle Alfred said, was because of the activities up at Stallery – but the sound of Mum’s typewriter is a constant hammering, through all four floors of the house.

She looked up as I came in and pushed back a swatch of dark grey hair. Old photos show her looking rather like Anthea, except that her eyes are a light yellow-brown, like mine, but you would never think her anything like Anthea now. She is sort of faded and she always wears what Anthea calls “that horrible mustard coloured suit” and forgets to do her hair. I like that. She’s always the same, like the cathedral, and she always looks over her glasses at me the same way. “Is lunch ready?” she asked me.

“No,” I said. “Anthea’s not even started it.”

“Then come back when it’s ready,” she said, bending to look at the paper sticking up from her typewriter.

“I’ll go when you tell me what pulling the possibilities means,” I said.

“Don’t bother me with things like that,” she said, winding the paper up so that she could read her latest line. “Ask your uncle. It’s only some sort of magicians’ stuff. What do you think of ‘disempowered broodmares’ as a description? Good, eh?”

“Great,” I said. Mum’s books are full of things like that. I’m never sure what they mean. That time I thought a disempowered broodmare was some sort of weak nightmare, and I went away thinking of all her other books, called things like Exploited for Dreams and Disabled Eunuchs. Uncle Alfred had a whole table of them down in the shop. One of my jobs was to dust them, but he almost never sold any, no matter how enticingly I piled them up.

I did lots of jobs in the shop, unpacking books, arranging them, dusting them, and cleaning the floor on the days Mrs Potts’ nerves wouldn’t let her come. Mrs Potts’ nerves were always bad on the days after she had tried to tidy Uncle Alfred’s workroom. The shop, and the whole house, used to echo then with shouts of “I told you just the floor, woman! You’ve ruined that experiment! And you’re lucky not to be a goldfish! Touch it again and you’ll be a goldfish!”

But Mrs Potts, at least once a month, just could not resist stacking everything in neat piles and dusting the chalk marks off the workbench. Then Uncle Alfred would rush up the stairs shouting and the next day Mrs Potts’nerves kept her at home and I would have to clean the shop floor. As a reward for this, I was allowed to read any books I wanted from the children’s shelves.

To be brutally frank with you – which is Uncle Alfred’s favourite phrase – this reward meant nothing to me until about the time I heard about karma and Fate and started wondering what pulling the possibilities meant. Up to then I preferred doing risky things. Or I mostly wanted to go and see friends in the part of town where televisions worked. Reading was even harder work than cleaning the floor. But suddenly one day I discovered the Peter Jenkins books. You must know them – Peter Jenkins and the Thin Teacher, Peter Jenkins and the Headmaster’s Secret and all the others. They’re great. Our shop had a whole row of them, at least twenty, and I set out to read them all.

Well, I had already read about six, and those all kept harking back to another one called Peter Jenkins and the Football Formula that sounded really exciting. So that was the one I wanted to read next.

I finished the floor as quickly as I could. Then, on my way to dust Mum’s books, I stopped by the children’s shelves and looked urgently along the row of shiny red and brown Peter Jenkins books for Peter Jenkins and the Football Formula. The trouble is, all those books look the same. I ran my finger along the row, thinking I’d find the book about seventh along. I knew I’d seen it there. But it wasn’t. The one in about the right place was called Peter Jenkins and the Magic Golfer. I ran my finger right along to the end, and it still wasn’t there, and The Headmaster’s Secret didn’t seem to be there either. Instead, there were three copies of one called Peter Jenkins and the Hidden Horror which I’d never seen before. I took one of those out and flipped through it, and it was almost the same as The Headmaster’s Secret, but not quite – vampire bats instead of a zombie in the cupboard, things like that – and I put it back feeling puzzled and really frustrated.

In the end, I took one at random before I went on to dust Mum’s books. And Mum’s books were different – just slightly – too. They looked the same, with FRANCONIA GRANT in big yellow letters on them, but some of the titles were different. The fat one that used to be called Women in Crisis was still fat, but it was now called The Case for Females, and the thin floppy one was called Mother Wit, instead of Do We Use Intuition? like I remembered.

Just then I heard Uncle Alfred galloping downstairs whistling, on his way to open the shop. “Hey, Uncle Alfred!” I called out. “Have you sold all the Peter Jenkins and the Football Formulas?”

“I don’t think so,” he said, rushing into the shop with his worried look. He hurried along to the children’s shelves, muttering about having to reorder as he changed his glasses over. He peered through them at the row of Peter Jenkins books. He bent to look at the books below and stood on tiptoe to look at the shelves above. Then he backed away looking so angry that I thought Mrs Potts must have tidied the books too. “Would you look at that!” he said disgustedly. “That’s a third of them different! It’s criminal. They went for a big working without even considering the side effects! Go outside and see if the street’s still the same, Conrad.”

I went to the shop door, but as far as I could see, nothing…Oh! The postbox down the road was now bright blue.

“You seel” said my uncle when I told him. “You see what they’re like! All sorts of details will be different now – valuable details – but what do they care? All they think of is money!”

“Who?” I asked. I couldn’t see how anyone could make money by changing books.

He pointed up and sideways with his thumb. “Them. Those bent aristocrats up at Stallery, to be brutally frank with you, Con. They make their money by pulling the possibilities about. They look, and if they see they could get a bigger profit from one of their companies if just one or two things were a little different, then they twist and twitch and pull those one or two things. It doesn’t matter to them that other things change as well. Oh no. And this time they’ve overdone it. Greedy. Wicked. People are going to notice and object if they go on doing this.” He took his glasses off and cleaned them. Beads of angry sweat stood on his forehead. “There’ll be trouble,” he said. “Or so I hope.”

So this was what pulling the possibilities meant. “How do they change things?” I asked.

“By very powerful magic,” said my uncle. “More powerful than you or I can imagine, Conrad. Make no mistake, Count Rudolf and his family are very dangerous people.”

When I finally went up to my room to read my Peter Jenkins book, I looked out of my window first. Because I was at the very top of our house, I could see Stallery as just a glint and a flashing in the place where green hills folded into rocky mountain. I found it hard to believe that anyone in that high, twinkling place could have the power to change a lot of books and the colour of the postboxes down here in Stallchester. I still didn’t understand why they should want to.

“It’s because if you change to a new set of things that might be going to happen,” Anthea explained, looking up from her books, “you change everything just a little. This time,” she added, ruefully turning the pages of her notes, “they seem to have done a big jump and made a big difference. I’ve got notes here on two books that don’t seem to exist any more. No wonder Uncle Alfred’s annoyed.”

We got used to the changes by next day. Sometimes it was hard to remember that postboxes used to be red. Uncle Alfred said that we only remembered anyway because we lived in that part of Stallchester. “To be brutally frank with you,” he said, “half Stallchester thinks postboxes were always blue. So does the rest of the country. The King probably calls them royal blue. Mind games, that’s what it is. Diabolical greed.”

This happened in the glad old days when Anthea was at home. I think Mum and Uncle Alfred thought Anthea would always be at home. That summer, Mum said as usual, “Anthea don’t forget that Conrad needs new school clothes for next term,” and Uncle Alfred was full of plans for expanding the shop once Anthea had left school and could work there full time.

“If I clear out the boxroom opposite my workroom,” he would say, “we can put the office in there. Then we can put books where the office is – maybe build out into the yard.”

Anthea never said much in reply to these plans. She was very quiet and tense for the next month or so. Then she seemed to cheer up. She worked in the shop quite happily all the rest of the summer and, in the early autumn, she took me to buy new clothes just as she had done last year, except that she bought things for herself at the same time. Then, after I had been back at school a month, she left.

She came down to breakfast carrying a small suitcase. “I’m off,” she said. “I start at University tomorrow. I’m catching the nine-twenty to Ludwich, so I’ll say goodbye now and get something to eat on the train.”

“University!” Mum exclaimed. “But you’re not clever enough!”

“You can’t,” said Uncle Alfred. “There’s the shop – and you don’t have any money.”

“I took an exam,” Anthea said, “and I won a scholarship. That gives me enough money if I’m careful.”

“But you can’t!” they both said together. Mum added, “Who’s going to look after Conrad?” and Uncle Alfred said, “Look here, my girl, I was relying on you for the shop.”

“Working for nothing. I know,” Anthea said. “Well, I’m sorry to spoil your plans for me, but I do have a life of my own, you know, and I’ve made arrangements for myself because I knew you’d both stop me if I told you. I’ve looked after all three of you for years. But now Conrad’s old enough to look after himself, I’m going to go and get a life.”

And she went, leaving us all staring. She didn’t come back. She knew Uncle Alfred, you see. Uncle Alfred spent a lot of time in his workroom setting up spells to make sure that when Anthea came home at the end of the University semester she would find herself having to stay with us for good. Anthea guessed he would. She simply sent a postcard to say she was staying with friends and never came near us. She sent me cards and presents for my birthdays, but she never came back to Stallchester for years.

Chapter Two

Anthea’s going made a dreadful difference, far worse than any change made by Count Rudolf up at Stallery. Mum was in a bad mood for weeks. I’m not sure she ever forgave Anthea.

“So sly!” she kept saying. “So mean and secretive. Don’t you ever be like that, Conrad, and it’s no use expecting me to run after you. I have my work to do.”

Uncle Alfred was tetchy and grumpy for a long time too, but he cheered up after he had set the spells that were supposed to fix Anthea at home once she came back. He took to patting me on the shoulder and saying, “You’re not going to let me down like that, are you, Con?”

Sometimes I answered, “No fear!” but mostly I wriggled a bit and didn’t answer. I missed Anthea horribly for ages. She had been the person I could go to when I had a question to ask, or to get cheered up. If I fell down or cut myself, she had been the one with sticking plaster and soothing words. She used to suggest things for me to do if I was bored. I felt quite lost now she was gone.

I hadn’t realised how many things Anthea did in the house. Luckily, I knew how to work the washing machine, but I was always forgetting to run it and finding I’d no clothes to go to school in. I got into trouble for wearing dirty clothes until I got used to remembering. Mum just went on piling her clothes into the laundry basket as she always had, but Uncle Alfred was particular about his shirts. He had to pay Mrs Potts to iron them for him and he grumbled a lot about how much she charged.

“The ingredients for my experiments cost the earth these days,” he kept saying. “Where do I find the money?”

Anthea had done all the shopping and cooking too, and this was where we all suffered most. For the week after she left we lived on cornflakes, until they ran out. Then Mum tried to solve the problem by ordering two hundred frozen quiches and cramming these into the freezer. You can’t believe how quickly you get tired of eating quiche. And none of us remembered to fetch the next quiche out to thaw. Uncle Alfred was always having to unfreeze them by magic, and this made them soggy and seemed to affect the taste.

“Is there anything else we can eat that might be less squishy and more satisfying?” he asked pathetically. “Think, Fran. You used to cook once.”

“That was when I was being exploited as a female,” Mum retorted. “The quiche people do frozen pizzas too, but you have to order them by the thousand.”

Uncle Alfred shuddered. “I’d rather eat bacon and eggs,” he said sadly.

“Then go out and buy some,” said my mother.

In the end, we settled that Uncle Alfred would do the shopping and I would try to cook what he bought. I fetched books called Simple Cookery and Easy Eating up out of the shop and did my best to do what they told me. I was never very good at it. The food always seemed to turn black and stick to the bottom of the pan, but I usually had enough on top to get by with. We ate a lot of bread, though only Mum got noticeably fatter. Uncle Alfred was naturally skinny and I kept growing. Mum had to take me shopping for new clothes several times a year from then on. It always seemed to happen when she was very busy finishing a book and this made her so unhappy that I tried to make my clothes last as long as I could. I got into trouble at school once or twice for looking like a scarecrow.

We got used to coping by next summer. I suppose that was when it finally became obvious that Anthea was not coming back. I had worked out by Christmas that she had left for good, but it took Mum and Uncle Alfred most of a year.

“She’ll have to come home this summer,” Mum was still saying hopefully in May. “All the Universities shut for months over the summer.”

“Not she,” said Uncle Alfred. “She’s shaken the dust of Stallchester off her feet. And to be brutally frank with you, Fran, I’m not sure I want her back now. Someone that ungrateful would only be a disturbing factor.”

He sighed, dismantled his spell to keep Anthea at home and hired a girl called Daisy Bolger to help in the shop. After that, he was always worrying about how much he had to pay Daisy in order to stop her going to work at the china shop by the cathedral instead. Daisy knew how to get money out of Uncle Alfred much better than I did. Talk about sly! And Daisy always seemed to think I was going to mess up the books when I was in the shop. Once or twice, Count Rudolf up at Stallery worked another big change, and each time Daisy was sure it was me messing the books about. Luckily, Uncle Alfred never believed her.

Uncle Alfred was sorry for me. He would look at me over his glasses in his most worried way and shake his head sadly. “I reckon Anthea going has hit you hardest of all, Con,” he took to saying sadly. “To be brutally frank, I suspect it was your bad karma that caused her to leave.”

“What did I do in my past life?” I asked anxiously.

Uncle Alfred always shook his head at that. “I don’t know what you did, Con. The Lords of Karma alone know that. You could have been a crooked policeman, or a judge that took bribes, or a soldier that ran away, or maybe a traitor to the country – anything! All I know is that you either didn’t do something you should have done, or you did something you shouldn’t. And because of that, a bad Fate is going to keep dogging you.” Then he would hurry away muttering, “Unless we find a way you could expiate your misdeed, I suppose.”

I always felt horrible after these conversations. Something bad almost always happened to me just afterwards. Once I slipped when I was quite high up climbing Stall Crag and scraped the whole front of me raw. Another time I fell downstairs and twisted my ankle, and one other time I cut myself quite badly in the kitchen – blood all over the onions – but the truly nasty part was that, each time, I thought, I deserve this! This is because of my crime in my past life. And I felt horribly guilty and sinful until the scrapes or the ankle or the cut had healed. Then I remembered Anthea saying she didn’t believe people had more than one life, and after that I would feel better.

“Can’t you find out who I was and what I did?” I asked Uncle Alfred, one time after I had been told off by the Headmistress because my clothes were too small. She sent a note home with me about it, but I threw it away because Mum had just started a new book and, anyway, I knew I deserved to be in trouble. “If I knew, I could do something about it.”

“To be brutally frank,” said my uncle, “I fancy you have to be a grown man before you can change your Fate. But I’ll try to find out. I’ll try, Con.” He did experiments in his workroom to find out, but he never seemed to make much headway.

About a year after Anthea left, I got really annoyed with Daisy Bolger, when she tried to stop me looking at the newest Peter Jenkins book. I told her my uncle had said I could, but she just kept saying, “Put it back! You’ll crease it and then I’ll be blamed.”

“Oh, why don’t you go away and work in that china shop!” I said in the end.

She tossed her head angrily. “Fat lot you know! I wouldn’t dream of it. It’s boring. I only say I will to get a decent wage out of your uncle – and he doesn’t pay me half what he could afford, even now.”

“He does,” I said. “He’s always worrying how much you cost.”

“That,” said Daisy, “is because he’s stingy, not because he hasn’t got it. He must be as rich as the Count up at Stallery, almost. This bookshop’s coining money.”

“Is it?” I said.

“I keep the till. I know,” Daisy said. “We’re at the picturesque end of town and we get all the tourists, winter and summer. Ask Miss Silex if you don’t believe me. She does the accounts.”

I was so astonished to hear this that I forgot to be angry and forgot the Peter Jenkins book too. That was no doubt what Daisy intended. She was a very cunning person. But I couldn’t believe she was right, not when Uncle Alfred was always so worried. I began counting the people who came into the shop.

And Daisy was right. Stallchester is a famous beauty spot, full of historic buildings and surrounded by mountains. In summer, we got people to look at the town and play the casino, and hikers who walked in the mountains. In winter, people came to ski. But because we are so high up, we get rain and mist in summer; and in winter there are always times when the snow is not deep enough, or too soft, or coming down in a blizzard, and these are the days when tourists come into the shop in their hundreds. They buy everything, from dictionaries to help with crosswords, to deep books of philosophy, detective stories, biographies, adventure stories and cookery books for self-catering. Some even buy Mum’s books. It only took a few months for me to realise that Uncle Alfred was indeed coining money.

“What does he spend it all on?” I asked Daisy.

“Goodness knows,” she said. “That workroom of his is pretty expensive. And he always buys best vintage port for his Magicians’ Circle. All his clothes are handmade too, you know.”

I almost didn’t believe that either. But when I thought about it, one of the magicians who came to Uncle Alfred’s Magicians’ Circle every Wednesday was Mr Hawkins the tailor, and he often came early with a package of clothes. And I’d helped carry dusty old bottles of port wine upstairs for the meeting, often and often. I just hadn’t realised the stuff was expensive. I was annoyed with Daisy for noticing so much more than I did. But then she was a really cunning person.

You would not believe how artfully Daisy went to work when she wanted more money. She often took as much as two weeks on it – ten days of sighing and grumbling and saying how overworked and hard up she was, followed by another day of saying how the nice woman in the china shop had told her she could come and work there any time. Finally, she would flare up with “That’s it! I’m leaving!” And it worked every time.

Uncle Alfred hates people to leave, I thought. That’s why he let Anthea go to Cathedral School, so she could stay at home and be useful here.

I couldn’t threaten to leave, not yet. You have to stay at school until you are twelve in this country. But I could pretend I was not going to do any more cooking. It didn’t take much pretending, really.

That first time, I went even slower than Daisy. I spent over a fortnight sighing and saying I was sick to my back teeth of cooking. Finally, it was Mum who said, “Really, Conrad, to listen to you, anyone would think we exploited you.”

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.