Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Birds Britannia"

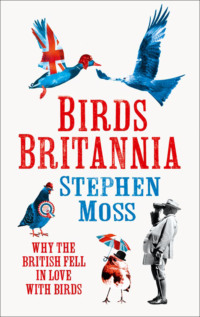

BIRDS

BRITANNIA

STEPHEN MOSS

HOW THE BRITISH

FELL IN LOVE WITH BIRDS

For Tony Soper

& Bill Oddie

Birders and broadcasters

par excellence

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Introduction

Garden Birds

Water Birds

Seabirds

Countryside Birds

Epilogue

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

We British are more obsessed with birds than any other nation on earth. From feeding ducks in the park to listening for the first cuckoo of spring, from inspiring some of our best-loved poetry to filling our stomachs, and from boosting the economy to providing comfort during times of crisis, birds have long been at the centre of our nation’s history. This unique relationship between the British and our birds reveals as much about us as it does about the birds themselves.

As birder, author and cultural historian Mark Cocker points out: ‘Bird song, bird flight, birds’ residence around us, cements our relationship with them, and there is no equal in our landscape – and that’s why birds are so important to the British.’

Partly, as we shall see in the opening chapter, Garden Birds, our passion for birds is a result of the major social changes that took place during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when our ancestors moved lock, stock and barrel from a rural, agrarian existence to an urban, industrial one.

Having shifted so dramatically from the countryside to the city, in just two or three generations, they developed a powerful nostalgia for the landscapes they had left behind, and for the wild creatures that lived there, especially the birds. In response, perhaps, to their sense of loss, they decided to create their own little piece of the countryside in their new home: and the British love of gardens began to blossom. With it came a new kind of relationship with the birds that visited our gardens; a relationship that today is still one of the closest and most meaningful of all our encounters with birds.

Jumping ahead to the final chapter, Countryside Birds, the strength of the British love of our countryside and the birds that live there is explored in greater depth. We discover how the birds of our countryside are inextricably linked with our appreciation of the landscape and what it means to us; how we celebrated their importance to us in many different ways; and how, as they have declined, this has threatened the very nature of what we mean by ‘countryside’.

But our relationship with birds has its darker side, too. The middle two chapters, on Waterbirds and Seabirds, reveal a more primal connection, expressed initially through the very basic need to hunt and kill birds for food and other commodities. Later this developed into the wider exploitation of bird populations for profit: whether for fashion or fertiliser, feathers or simply fun, the British have always been adept at making money out of birds. On a more positive side, the wholesale slaughter of these birds eventually prompted a reaction against such wanton cruelty, leading to the rise of the bird protection movement, in which the British led the world, and – along with our neighbours across the Atlantic in North America – continue to do so today.

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw the development of a recreational interest in birds: largely taking the form of shooting and killing them for sport. But during the course of the twentieth century, and into the new millennium, our passion for birds took a more benevolent, and less destructive, direction. This was through the hobby, pastime or obsession (call it what you will) of birdwatching – or birding, as it is now more usually known. Again, Britain leads the world: with more than one million members of the RSPB, half a million people taking part in Citizen Science projects such as the Big Garden Birdwatch, and tens of thousands of enthusiasts actively going out to watch birds every weekend. Along with sport, cookery and gardening, birding has now become one of our major leisure activities, and in a world where our concern for the environment is growing, its popularity looks set to continue.

The impulses behind why we watch birds are almost as varied as the people who do it – few other pastimes cross quite so many social and demographic boundaries, appealing to people of all ages, backgrounds and classes. As the great ornithologist and media man James Fisher wrote at the start of the Second World War:

Among those I know of [who watch birds] are a Prime Minister, a President, three Secretaries of State, a charwoman, two policemen, two Kings, two Royal Dukes, one Prince, one Princess, a Communist, seven Labour, one Liberal, and six Conservative Members of Parliament, several farm-labourers earning ninety shillings a week, a rich man who earns two or three times that amount in every hour of the day, at least forty-six schoolmasters, an engine-driver, a postman, and an upholsterer.

A similar list compiled today would be even more wide-ranging and inclusive.

As to why we enjoy watching birds so much, perhaps it is because it appeals to many different human impulses and instincts, as Fisher rightly pointed out: ‘The observation of birds may be a superstition, a tradition, an art, a science, a pleasure, a hobby, or a bore; this depends entirely on the nature of the observer.’ Birds Britannia explores this eclectic passion, taking us on a journey from exploitation, through appreciation, to delight.

STEPHEN MOSS

Mark, Somerset

January 2011

Garden Birds

Of all Britain’s birds, one particular group has risen to the very top of our affections – those that have chosen to live alongside us, in our gardens. These have become the most familiar, the most loved and, in some cases, the most hated of our birds. In some ways they define our relationship with Britain’s birdlife, as birder and broadcaster Bill Oddie points out: ‘For many people there is nothing but garden birds – the only birds they actually see are in their garden!’

It’s hardly surprising we are so obsessed with garden birds, for they perform a daily soap opera outside our back window; a soap opera whose characters reflect our own attitudes, prejudices and emotions.

These are our most familiar birds: those we see every day and interact with most in our lives. Not surprisingly, this has engendered a very deep and intimate relationship between us and the natural world, as David Attenborough reflects:

No matter how small your garden is, there will be a bird that comes to it. And they bring a breath of the natural world, the non-human world, and they’re the one thing that does. They’re also magical, in that they suddenly take off and disappear and you’ve no idea where they’ve gone – yet they come back again.

And yet our relationship with garden birds is a surprisingly modern one. It is the result of some of the most dramatic changes in British society in the last hundred and fifty years.

* * *

We are a nation of gardeners who have become a nation of garden-bird lovers. Our long and cherished relationship with our gardens is clear from the huge popularity of television and radio programmes such as Gardeners’ World and Gardeners’ Question Time, as well as the plethora of gardening magazines on sale in our newsagents. This has undoubtedly helped to influence and define our relationship with the birds that live alongside us.

Today, two out of three of us feed wild birds in our gardens, spending over £150 million pounds a year in the process. This relationship brings a mutual benefit, whereby the birds are fed, and we are entertained by watching them. And for many people, this simple act of kindness to our fellow creatures is the entry point into a deeper relationship with wildlife as a whole; a relationship that may span their entire lifetime.

Yet only a century ago, most of us did not even have gardens. We took little interest in the welfare of our feathered neighbours, and were more likely to eat a Blackbird than to feed it. The very concept of ‘garden birds’ was meaningless – as environmental historian Rob Lambert points out, the term hadn’t even been invented: ‘“Garden birds” is a cultural construct – these are simply birds that have taken advantage of the new suburban landscapes we have created. These are birds of the woodland edge that have moved into what we have defined as “gardens”.’

As the landscape of Britain changed, so birds that had evolved to live in our woods and forests – tits, thrushes, woodpeckers and many more – found sanctuary in our gardens. They were joined by birds of more open countryside – finches, pigeons and doves – that also exploited the plentiful opportunities for food, shelter and nesting places in our backyards.

As the wider countryside became less and less suitable for birds, due to the intensification of agriculture and the resulting loss of habitat, so gardens became the prime habitat for many of these species – effectively turning them from woodland and farmland birds into what we now call ‘garden birds’.

So in little more than a century, an extraordinary transformation has taken place in our relationship with the birds that live alongside us. This domestic drama runs parallel to the history and development of that very British phenomenon, the modern suburban garden. But it’s a story that begins ten thousand years ago, when one adaptable little bird sought out our company for the very first time: the House Sparrow.

* * *

The House Sparrow is often taken for granted, but it is a particular favourite of birder and broadcaster Tony Soper: ‘It’s a small, chunky little bird, with wonderful chestnuts and browns – in a drab sort of way it’s a very colourful bird. But mostly what’s good about the sparrow is its behaviour – the cheeky “cockney spadger”!’

House Sparrows have lived alongside humans longer than any other wild bird – since our prehistoric ancestors first abandoned their hunter-gatherer lifestyle in favour of farming, leading to a more settled way of life, as Mark Cocker explains:

The sparrow’s engagement with us is peculiarly intimate, and is rooted in the development of agriculture. Agriculture is thought to have originated in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East, and House Sparrows probably spread across Europe, as agriculture was spread from community to community. And as they moved, they found a way to live beside us.

Sparrows found nest sites on our homes and food in our fields and farmyards. Indeed they are now only found in and around human settlements, and have spread, via deliberate and accidental introductions, across much of the globe. Today the familiar chirp of the House Sparrow can be heard in towns and cities in North and South America, Africa, Australia and New Zealand; and in many of these places they have exploited vacant ecological niches to the detriment of native species.

But in the view of Denis Summers-Smith, an amateur ornithologist who has studied sparrows for more than sixty years, their very dependence on us meant that we viewed them with suspicion from the outset: ‘Sparrows, from very early on, were regarded as pests, because they fed on the cereal crops the farmers were growing.’

By the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, in the second half of the sixteenth century, sparrows had a price put on their heads, thanks to the passing of an Act of Parliament branding them as agricultural pests. As a result, people would take the head of each sparrow to the parish church where they’d be paid a small bounty.

Since that time, farming communities all over Britain have waged war on sparrows to safeguard their crops. Mark Cocker believes that this has had long-term consequences, helping to define our current relationship with this familiar little bird: ‘One of the interesting things about sparrows is that they’ve never really lost a shyness, a difficulty of approach, in the way that Blue Tits and Robins have lost their fear of us… And I think that’s to do with the way that because they ate grain they were harvested and eaten.’

But it’s not all that easy to catch such a clever bird – so in the seventeenth century our ancestors turned to the Netherlands for a practical solution, according to Denis Summers-Smith:

Dutch engineers who had come over to drain the Fens brought with them what were known as ‘sparrow-pots’. These were put up on farm buildings, primarily to prevent the sparrows nesting in the thatch; but also, because they were on a hook, they could be lifted off. The housewife could put her hand in the back and remove either the sparrows or the eggs, and these would very often go into a pot in the kitchen.

The number of tiny eggs required to make a decent omelette, or birds to make a pie, might appear hardly worth the trouble of collecting or catching them. Yet it must have been worthwhile, as this practice continued far longer than we might imagine – sparrows were caught and eaten in the countryside until the middle of the twentieth century.

But some Britons had already begun to take a very different view of this little bird, as a result of the biggest social change in British history. This was the wholesale migration of millions of people from the countryside into the towns, to meet the increased need for labour in factories required by the Industrial Revolution. Rural historian Jeremy Burchardt regards this as a key turning-point in the history of our nation:

In the nineteenth century the balance of population between rural England and urban England changed quite dramatically. In the early nineteenth century the great majority of people lived in the countryside; by 1900 only about one in five people did. So we had effectively changed from being a rural nation into being an urban nation in the space of a few generations.

Given how dependent House Sparrows were on humans, it’s not surprising that, as we moved into towns, they were the one bird that came along with us. They were partly able to do so because, as historian Jenny Uglow explains, the differences between urban and rural areas were not all that great:

One aspect to the growing cities is that they were still terribly close to the country; not just physically, but the fact that there were a lot of agricultural animals actually in the city. You had horses everywhere, you had stables, and also in the parks – like in St James’s Park in London – there were cows, there were sheep. So those birds which thrive on dung and seeds like the sparrow could find the city quite a happy home.

Arguably sparrows enjoyed better living conditions in Victorian cities than did much of the human population. Denis Summers-Smith notes that these newly built dwellings created to house the growing human population provided safe for the birds too: places to nest, where they were safe from attack by birds of prey and cats.

But the other reason for the success of sparrows in our towns and cities was a change in our attitude towards them. People rather welcomed the presence of this little bird, which perhaps reminded them of their ancestral home.

The townsfolk’s new-found affection for sparrows was undoubtedly a reaction to urbanisation – a disorientating process that cut millions of Britons off from wild nature, and at the same time made them nostalgic for their rural past. This was the start of a very new way of looking at the ‘countryside’ – not as a place where people lived and worked, but as a rural idyll of peace and harmony. This view would later come to define the relationship between town and country – a relationship that persists even today.

Meanwhile, back in the ever-growing cities of the Victorian era, the working classes and the urban poor found themselves living in densely packed housing with little if any outdoor space, and no trees or greenery. But they found one way to reconnect with the birds of the countryside – not outside the home, but within it.

* * *

Like us, the Victorians were obsessed with birds. Unlike us, they preferred to keep them in cages, rather than watch them in the wild. The cagebird craze became a big part of domestic life, and as well as what historian of science Helen Macdonald calls ‘the usual suspects’ – Canaries and Budgerigars – the Victorians also kept a very wide range of British species, including Wheatears and thrushes, as well as more typical cagebirds such as finches.

These birds were trapped in vast numbers – tens of thousands were caught at popular sites such as the South Downs in Sussex – and sold in London markets such as Club Row in London’s East End. They were caught using a variety of ingenious methods: smearing branches and twigs of trees with ‘bird-lime’ (a glutinous substance made from, amongst other things, holly bark), and by using large nets, which were laid out onto the ground and triggered by pulling a piece of string. Decoy birds were often tethered next to the nets, as a way of luring wild birds in. Spring and autumn were the main bird-catching seasons, as they coincided with the seasonal migrations of the birds.

The Victorian journalist and social reformer Henry Mayhew, who in 1851 wrote London Labour and the London Poor, made a special study of the bird-catchers. He reported that the majority of birds caught were Linnets, an attractive little finch with a sweet and melodious song. Up to 70,000 Linnets a year were being trapped, and sold for three or four pence each – though mature birds with particularly good songs could be sold for as much as half-a-crown (about £12 at today’s values). Goldfinches were also popular, and sold for between sixpence and one shilling a head – equivalent to a few pounds today. For the people involved in bird-catching, it must have been a profitable trade.

The Linnet’s widespread popularity as a cagebird was celebrated in the lyrics of the popular music-hall hit, ‘My Old Man’, written by Charles Collins and Fred Leigh:

My old man said ‘follow the van,

And don’t dilly dally on the way!’

Off went the van with my old man in it,

I walked behind with me old cock linnet…

A more literary example can be found in Charles Dickens’s novel Bleak House, in which one memorable scene, also shown in the BBC television adaptation in 2005, dramatises the Victorian passion for cagebirds. One character, old Miss Flite, is embroiled in a long-running court case, but takes comfort in her collection of birds in cages, which she vows to release once the case is finally settled.

Cagebirds weren’t kept for purely aesthetic reasons, but because they brought a reminder of the Victorian city-dwellers’ rural past into their homes, according to Jenny Uglow: ‘The song of the bird was like the music of the country; and you could close your eyes, and listen to the bird sing, and be transported back to the countryside that you came from. For people in the city, the wild bird becomes an emblem of the freedom they have lost.’

To our modern sensibilities, the notion that birds in cages could be symbols of freedom may seem bizarre. And indeed for some time there had been growing numbers of people objecting to the practice, including the poet and reformer William Blake. In ‘Auguries of Innocence’, written in the early nineteenth century but not published until 1863, he unequivocally condemns bird-keeping, in a celebrated couplet:

A robin redbreast in a cage

Puts all heaven in a rage.

According to the historian Keith Thomas, author of Man and the Natural World, wild birds were often invoked as symbols of an Englishman’s freedom, while a growing movement objected to the cruelty involved – not simply imprisoning the birds, but also blinding them, a common practice supposed to improve the quality of their song. But the trade continued, and as Jenny Uglow points out, for many Victorians keeping birds in cages was not regarded as cruel in any way. She cites contemporary accounts of species such as Goldfinches being happy in their cage, and appearing to sing more frequently than they did in the wild.

Not surprisingly, the most popular cagebirds were those with the most attractive song, including the Nightingale, justly famed as the greatest and most varied of all our native songsters. But this insectivorous bird would have been very tricky to keep and look after as a cagebird, as Tim Birkhead, author of The Wisdom of Birds, explains: ‘The Nightingale was a very difficult bird to keep in captivity, requiring live food such as worms and insects, and as a result having very wet droppings, so you had to go to a lot of trouble to keep it – both to feed it and to keep it clean.’

Fed up with the problems of keeping such a fussy bird, the Victorians looked around for a more convenient alternative. They found it not in a wild British bird, but in an imported exotic species, the Canary which, as Tim Birkhead puts it, ‘knocked the Nightingale off its perch’.

* * *

But whether exotic or British, caged birds served another purpose beyond their song and attractive appearance. Birds in cages were regarded by the Victorians as excellent examples of moral instruction, especially as a way of teaching children, as Tim Birkhead explains: ‘If you had a pair of Canaries in a cage, and they were breeding, you could see “mum and dad” feeding the chicks – they were, in a way, like a model human couple.’

Because the Victorians believed birds paired for life, unlike many other creatures, the Christian Church had singled them out for special attention. One clergyman was particularly influential in shaping attitudes to birds at this time. Tony Soper notes: ‘The Reverend Francis Orpen Morris was typical of the clergy of his day, in that he regarded all bird life as moral creatures from which we had to learn.’

F. O. Morris, as he is generally known, was one of the great Victorian popularisers of birds. In his long life – he lived more than eighty years – he published numerous books on many and varied subjects, including British birds. His most celebrated work, A History of British Birds, appeared from 1851 to 1857.

Like many Victorian works, both of fiction and non-fiction, A History of British Birds was published in regular ‘partworks’ costing a shilling each, which made it accessible to a very wide audience. Eventually bound into six hefty volumes, it was subsequently reprinted at regular intervals, and even today hand-coloured plates from this work can be found in antique shops all over the country.

Popular, the Reverend Morris’s work may certainly have been; accurate and informative it was not. This damning verdict, written in 1917 by ornithological bibliographers Mullens and Swann, is fairly typical:

Of this it may be said that, although one of the most voluminous and popular works on the subject, and financially most successful (thousands of pounds having been made out of successive editions), yet it has never occupied any very important position among the histories of British birds. Morris was too voluminous to be accurate, and too didactic to be scientific. He accepted records and statements without discrimination, and consequently his work abounds with errors and mistakes.

Their verdict isn’t entirely negative, and acknowledges that popularity has its virtues: ‘Yet as a book for amateur ornithologists it has charmed and delighted for more than half a century, and it had for many years the great merit of being almost the only work at a moderate price to give a fairly accurate and coloured figure of every species.’

But like so many Victorian clergymen who used nature as a way of teaching morals to their flock, Morris’s lack of a basic understanding of biology let him down – in his case, very badly indeed. For amongst his favourite birds – and one he frequently invoked as an example to his parishioners and readers – was the Hedge Sparrow, now known as the Dunnock.

Despite its superficial resemblance to the House Sparrow, the Dunnock is in fact completely unrelated to that species. It is the only common and widespread representative in Britain of a small family known as the accentors: mostly birds of high mountains and rocky slopes, found entirely in the temperate regions of Europe and Asia. Its name, dating back to the fifteenth century, simply means ‘little brown bird’.

Dunnocks are rather retiring birds, easy to overlook, as Tony Soper notes: ‘The Dunnock is a shy little bird, a reclusive little bird, that walks around the bottom of the bird table picking up the crumbs. And yet it’s one of these birds that, when you get a really good, close-up look at it, has a really fine plumage, with pinkish legs and a nice little thin bill.’

It was this shyness and modesty that appealed so strongly to the Reverend Morris, as Tim Birkhead points out: ‘Humble in its behaviour, drab and sober in its dress, this was the perfect model for how all his parishioners should behave.’

But then again, the Reverend Morris didn’t know the truth about the Dunnock. As Jeremy Mynott, author of Birdscapes, notes, the sex life of this species is truly extraordinary: ‘It enters into every relationship possible: polygamy, polygyny, polyandry, promiscuity… you name it, the Dunnock does it!’

Sometime during the early part of the year, just as the days begin to lengthen, male Dunnocks leave their hiding places in the shrubbery and are miraculously transformed from shy wall-flowers into loud, self-confident show-offs.

Usually sitting in full view on a hedge, tree or fence post, the male sings his rather flat, tuneless song from dawn to dusk. Like any other songbird at this time of the year, he’s trying to attract a mate. Unlike many other birds, he won’t be content with just one.

Having formed a pair-bond with a female, the male Dunnock spends much of the day following her doggedly around – demonstrating the apparently faithful behaviour that so appealed to Morris. But he’s not doing this out of devotion, but jealousy; because every female Dunnock is keeping half an eye out for a neighbouring male – a rival to her mate. If she can shake off his attentions for a moment or two she will mate with the other male, as Tim Birkhead explains: ‘Dunnocks, instead of breeding as a conventional pair, often breed as a trio: two males paired simultaneously with one female. The female wants both males to mate with her, because if both males mate with her they will both help to rear her chicks.’

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.