Buch lesen: "I Am The Emperor"

Stefano Conti

© Copyright 2021 by

Stefano Conti

Translation by Arianna Vanin

of Io sono l’imperatore, Ancona 2017

Imprimé en janvier 2021 par

Rotomail Italia spa

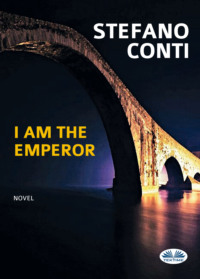

On the cover:

graphic elaboration from photos of the author

of the Ponte della Maddalena or Ponte del diavolo.

Borgo a Mozzano, Lucca (Italy).

Stefano Conti

I am the emperor

UUID: a1b86bee-a976-41b6-aa2e-a4efc93c7ee6

This ebook was created with StreetLib Write

Table of Contents

Cover

I am the emperor

Preface

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

Preface

26 June 363 AD

T he battle between the roman army and the Persians is raging. Suddenly time seems to stop: a javelin pierces Julian’s abdomen.

«Come quick, the emperor has been hurt!»

The young king sways on the saddle of his horse and falls. Lying on the ground he tries to take out the sword, blessing his fingers.

«Leontius, take off this spear.»

«I cannot, my lord. You would die.»

«I am already dead.» The blood flows incessantly. «I am just asking to finish my days as a warrior: help me get back on my horse.»

The trusted soldier, for the first time, does not obey: «Call Oribasius, quick!»

Julian understands this is the day marked by fate: «I did not want to listen to the haruspices, but I knew that falling star was announcing my end».

Oribasius, his personal doctor, tries to stop the haemorrhage in vain.

The prince looks at him benevolently: «Do not trouble yourself. The gods are waiting for me… I’m ready».

His doctor and friend takes him from under his arms: «Leontius, help me take him back to camp.»

«No!» Julian stops them. «I ask a last favour of you: take me to the Tigris’ shore.»

In the meanwhile, Maximus arrives, he is the spiritual guide of the emperor-philosopher: «He is inspired by Alexander the Great. He wants to throw himself in the river and let his corpse disappear among the waves. When his body has vanished forever, we will say he ascended to the Olympus on a fire chariot. Thus, we pagans will celebrate a new god: Julian!»

But a squad of soldiers blocks the access to the river: «Stop! We Christians won’t let this happen. No one dares, now or never, let the Apostate’s body disappear. We will forbid anyone to lie about him ascending to heaven».

Julian looks at the earth soaked with his blood and turns his eyes to the sky: «Helios, here I come!»

I

Friday, 16 July 2010

T oday’s terrible heat really does not make it a suitable day for flying, but none of them is: I am always afraid when I’m not the one driving, even if it was a little sleigh on a field of soft snow. In Dustin Hoffmann/ Rain Man ’s list, was Turkish Airlines among the companies that fall?

While I’m standing in the corridor of the plane, waiting for a couple of elderly people taking care of their bags, a steward arrives. He addresses the lady, who just sat: «Apologies, madam, you cannot sit there».

«It is my husband’s seat, but…»

«I left the window seat to my wife» says the man, in his seventies. «You know, she likes watching outside.»

«I understand, sir, but you must take that seat» the guy insists.

«And why is that?» asks the lady, who does not want to get up again.

«Because» explain politely the steward «that window is also an emergency exit and you would not be able to open it, in case of…»

«There is… that possibility?» I ask.

The steward answers to the elderly tourist: «Just in case… you would be able to force the door open, I don’t think that your wife could».

«Ah, just in case» I repeat, moving away from them, clearly preoccupied.

I sit down. I hide my mp3’s headphones with my hair, covering the ears (I am sure it does not make any sense to turn off electric equipment). An old song from Vecchioni covers the sounds of the most critical phase: take-off.

The landing in Ankara is smooth but, in any case, when I get off, I wish I could kiss the land, just as the pope did. The air is unbreathable, the tar of the airstrip is scorching. All airports are the same: same panels, same gates’ disposition. Will I find my suitcase or would it be lost somewhere around Saint Petersburg? Unbelievably my case is there and, at the second attempt, I catch the right one (suitcases too all look alike: I should attach a name tag sooner or later).

The queue at customs is slow; when my turn arrives, having done my PhD in Germany finally turns out useful: no one speaks Italian abroad.

« Sprechen Sie Deutsch?» I ask.

« Ja» answers the officer, bluntly.

I take my passport out of my man bag and give it to him. He carefully looks at the picture, then turns up his eyes to meet mine and looks at the picture again, finally he asks if I am Francesco Speri.

I nod. I actually don’t really look much like I did 5 years and 12 kilos ago.

The look on his face becomes suddenly serious.

« Können Sie mir folgen?» he says in a martial tone.

Surprised by his request to follow him, I ask, maybe a little unkindly, why. The customs officer insists relentless and I am forced to follow him.

We cross a long dark corridor, many doors on its sides, all closed: it looks like a gloomy ancient hospital, of those you only find now in little villages. With a sign of the hand, he invites me to get into the last room on the right: here a small man, standing on his military boots dictates something to another man, who is in turn busy typing on an ancient machine. Despite his height, the first man must be a major, a coronel, some big shot. With a half-smile under his black moustache, he shows me where to sit gripping with his fat hand onto the back of an uncomfortable wooden chair. This “bossy” then loudly starts arguing with the man who took me here; the third officer stops typing and joins the conversation, but they immediately shut him up. For the first time since when I left, I think about professor Barbarino, who is the actual reason of my trip: he insisted I should have learnt Turkish to come here digging with him. I always answered that I am not an archaeologist but an historian and that in order to dig archaeological sites, speaking is not required; for all the rest it sufficed that he could be able to speak with the authorities.

Anxiety takes over, while the minutes slowly go by. The officers are literally screaming now and I suppose they are talking about me: from time to time they point towards me with a slight movement of the head. I look around: a brownish wallpaper has been poorly glued to the white tiles. On the wall behind the general (I have upgraded him in the meanwhile: he seems to be the one in charge) hangs a huge painting of someone wearing a high officer uniform.

« Haben Sie verstanden?»

[How could I understand, if you only speak in this Anatolian western mountain lost dialect!]

They explain someone from the Italian embassy is on their way; I ask them why, but no one deems worthy responding. This “general” smiles a lot and talks very little: I don’t trust him instinctively!

The officer who took me here asks, or better orders me, to follow him again. On my way out I realise that probably the painting on the wall pictures the same younger general; after all men with moustache all look alike to me.

We walk back the same corridor up until a room that seems even gloomier: no bars, but still looking like a prison cell, probably because there are no windows or, mainly, due to the officer standing right on the door, as to block it with his body size.

A never-ending hour goes by, locked up in that room: I don’t know what could happen to me. Suddenly I hear the sound of heels approaching from afar, it stops, undefined voices can be heard, and the heels keep coming closer…

«Good morning, my name is Francesco Speri» I say standing up.

A girl around 35 comes in, short, with long hair: «Good morning, my name is Chiara Rigoni, I am the interpreter from the embassy».

I shake her hand a long time, as if I wanted to grasp onto it as to a lifeline: «I don’t understand what happened! They have been talking a lot between themselves, I don’t know about what, and then they locked me up here and…»

The officer, who is now bending on the door side in a nonchalant way, interrupts me talking in Turkish to the newcomer.

«They clarify that you weren’t locked up; you were here waiting for me. In any case I’m going to talk to lieutenant Karim» says this girl, Chiara, going out.

Is she Italian or Turkish? Her pale skin and blond hair, even if not completely natural, do not let you opt for the Turkish option, but her ways, too formal, have nothing to do with the Italians. Anyways, black moustache is a lieutenant!

In the meanwhile, the officer got back to standing in the middle of the way: they might have not lock me up, but I still feel like suffocating. A sudden doubt: «Excuse-me, you understand Italian, then?»

He denies a monotonous way, hence confirming my suspect. I stood up to ask him that question, but with a despotic gesture he “suggests” going back to my place; I don’t see the point in arguing, so I crouch back down.

The long wait, afraid of what might happen if I stand up, gives me a sudden image of one of the many Sundays spent looking at the match from the bench of my team when I was a kid: I wanted but feared at the same time, the moment I would be called in.

I never was strong as a football player and in a country like Italy, I must admit, it is almost heresy: a man, as such, must be able to play. I tried as a forward, since anyone who plays soccer only has one purpose: strike a goal. I soon realised that I rarely achieved it and sooner than me the coach, who put me in midfield. With the new coach (bleachers are not only volatile in first league) I was immediately moved to defence, where I learnt one only move: throw myself into a slide to the floor when the forward came; generally, I missed the ball and, luckily, also the opponent’s legs. It was the only thing I could do, so that they moved me even more to the back: goalkeeper. I could not go further, unless I became a ball boy: humiliation from which I escaped, leaving the team beforehand. But for at least one year I got to be goalkeeper, or better, assistant goalkeeper. Nowadays in first league goal posts you find many youngsters, surrounded by top-models, but at the time nobody wanted to take that place (you could not score from there) and only the “goofiest” of the team was sent there. Well, lucky me, I was his assistant!

I stand up from the Turkish customs “bleachers” only when I hear the stamping of the heels again…

«Everything’s fine: I will accompany you now to request a temporary document for your stay here. You will get your passport back on Monday» says the interpreter.

«What’s wrong?»

«Just a background check» she tries to calm me, making me more anxious. «Lieutenant Karim needs to wait permission to release form the Ministry, which will only open on Monday. In the meanwhile, we must speed to the embassy: they close in an hour.»

I follow her grey striped suit outside that terrible place. Taxis in Turkey are yellow, as in most parts of the world, but this one is of an unexpected pastel pink colour. The girl is nice but distant; while she distractedly looks outside the window, I get her to be on first name terms with me for the rest of the trip. In few words she tells me her parents are Italian, but she was born and raised in Turkey: she learned Italian from them. They own an ice-cream parlour in a small village near Ankara, but never adapted to speaking Turkish.

«I’d like to visit Italy: Venice, Padua, Iesolo, Oderzo…»

We might have some other nice cities, in Tuscany and the rest of the peninsula, but I sense that her parents are Venetians and I won’t argue. In Germany too all ice-cream parlours belong to Venetians: that region seems to be for the cone, what Campania is for the pizza.

At the embassy they give me a piece of paper. It should grant me to circulate freely, but seeing how the trip started…

«I don’t think I will go very far with this document. I’m not here on holiday, but to take back to Italy the corpse of my professor, alias ex-boss…»

«Is he buried in Ankara?» she asks, not fully understanding.

«Luigi Barbarino, that’s his name, died one week ago, while digging an archaeological site: Tarsus. I need to go there to get the corpse back…»

«A friend of mine lives in Tarsus… actually, an ex-friend: he can help you. He’s an engineer in a petrochemical plant. I’ll give you the address» she says tearing a page off her agenda and scribbling on it.

I would not take too much advantage, but: «Thanks, but how do I do with the language?»

«He speaks Italian well» she says almost angry. «I taught him.»

«Could you give me his mobile phone number, so I can give him a call from here?»

«Actually, I deleted it, but if you go to this address you’ll find him for sure. Say that Chiara sent you.»

She treats me like a child: she takes me to the bus station, gets a ticket on my name and puts me on a coach. Her perfume is a blend of Oriental mysteries. I go away, but not before having written on a paper my phone number.

From outside the bus to Tarsus looks nice, in its 60’s style and as soon as I get on, I understand it really is still in that years. Moreover, everyone smokes: the air is unbreathable. Luckily in the sixties you could still open the windows: I spend the six hours journey with my head outside, just like dogs do (who knows why!). With my head out like that, I can see Ankara, until now I just knew its sad looking offices. The buildings remind me of the endless stretch of grey London houses, with one difference: here they are crumbling! For a moment I erase homes and mosque’s domes and try in vain to see the column that the city of Ancyra (Ankara in roman times) built to honour the emperor Flavius Claudius Iulianus.

Dear Julian!

I’ve really been obsessing over the last pagan emperor of the roman era for ages now: when I worked at the University, I wrote several articles and a couple of books about him. His conversion from Christianity to paganism caused him to be named the Apostate and for all his short life he tried to attract new worshippers, reforming the traditional religion: his utopia was to get the whole empire, now unavoidably Christian, back to its pagan roots. The whole reason of his charm to me is here: Emperor Julian wanted to change the world, without realising that the world had changed already, but in a different direction and there was no going back. While I was still on the plane, I promised myself that the philosopher emperor’s column would be the first thing I’d see in Ankara, but with all that bureaucratic mess…

It is actually Julian the reason I came to Turkey: the official mission is to get back the remainders of poor Barbarino, but I’m here mostly to see the dear emperor’s tomb, never found until now, and that the professor, shortly before his death, told me in a letter he had finally discovered!

The bus is proceeding at a high speed on an endless desert plain. I fall asleep imagining to be in one of those American movies where the protagonist travels the States coast to coast.

Meanwhile in Ankara, lieutenant Karim, the one from that never ending afternoon at the customs, gets back home where his two sons are waiting for him; their mother left years ago.

Aturk, the oldest, was standing behind the doors from several minutes and he slams it open when he hears the noise of his father’s old car. «So, are they giving it to me?»

«Don’t we say hello anymore?» answers grouchy his dad.

«Welcome back, Mr lieutenant» says Aturk in a mockingly serious tone, then he repeats: «Will I get it?»

Karim does not answer, he enters his house, leaves the uniform jacket on the coat hanger and goes sitting on a brown armchair in the living room; his son follows him.

«They haven’t told me anything.»

«Can’t you just call them? Do you realise how important this is?»

«I know» he says grumpy. «Get me something to drink.»

The lieutenant gets up to pick up his jacket again, he takes a small black leather diary from a pocket, goes back to the armchair and dials a number on the phone: «Good evening, this is…»

«Don’t say your name!» The voice at the other side immediately interrupts him. «I told you not to call.»

«Yes… I know, but, you see…»

The mysterious voice cuts him: «Did you do what I asked?»

«Yes, Mister…»

«I told you: no names!»

«Well, that Italian: we stopped him and hold him until we could. Now he has a document from the embassy, he will get back his passport only on Monday.»

«Good! Remember: when he gets back to Ankara with the coffin, do as we told you.»

«Yes, seal it well and carve the letters…»

«Follow the instructions» stops him abruptly the voice.

The lieutenant proceeds, fearful: «Of course. I wanted to know if, as agreed, my son…»

«He can apply.»

«So, you guarantee he will…»

The voice again: «I told you he must apply: this means he will succeed!»

«I… Thank you.»

«Goodbye. Don’t call here ever again!»

«Thanks again and good night.»

Aturk enters from the kitchen, slowly and goofy watching out not to let a single drop fall from a glass full of a low-quality white wine: «So?»

«You can apply.»

His son doesn’t understand either: «I’ve got the application ready since months ago…»

«I told you to apply: the place is yours.»

«Thank you, thank you» Aturk gets closer to his dad, as to kiss him. He just hugs him, to be coldly hugged back.

«Come on, go make dinner for you and your brother now.»

The lieutenant sips his wine slowly, before going to bed, satisfied with what he had done during his day.

Saturday 17 July

I fell asleep California dreaming and I wake up in the middle of traffic noises and undistinguished yelling, while the bus gets slowly into the station: Tarsus reminds me of Palermo, which, according to the movie Johnny Stecchino is famous for its chaotic traffic.

I walk to the city centre, or at least what I imagine it to be: there is a monumental door from the roman era (might this be the renowned door where Antony met Cleopatra before Actium’s defeat?). Here no one speaks German, I just show the paper with the engineer’s address to anyone I meet: between gestures and half English words, they show me a road running along the Berdan river. My classical memories remind me that is the Cydnus, famous in ancient times for its transparent but freezing waters, which almost caused Alexander the Great’s drowning. Now it’s reduced to a disgusting blackish river, due to the many industrial petrol waste discharges from the area, I assume. I ring the bell at number 60, a sort of stilt house: an old hunchbacked lady opens the door.

«I am looking for Fatih Persin…» I ask, a little distracted, in my own language.

«Italian, come in Italian» the old lady smiles, showing her few remaining teeth and inviting me in with her hand. She then runs away up the stairs.

This house is weird looking: half laying on the river, it is almost empty of any objects or furniture, but very original in its style. I make myself comfortable on a red wooden chair, the seat made of woven straw. The smell of meat sauce slowly cooking has filled the whole dwelling.

From the unstable step ladder that comes out of an opening in the ceiling, a man in his forties comes down, tall and thin, very tall and too thin: «Good morning, I am Fatih» he shakes my hand and says something in Turkish to the lady.

«I am Francesco Speri, Chiara gave me your address… Chiara…» I forgot her family name.

«Rigoni» he finishes a bit surprised. «What I do for you?» The engineer has some trouble with Italian, but we manage to communicate; while he sits, his mother, or at least I think, comes in with a tray and two big cups of coffee. The look is not very tempting: something is floating in it and the smell is sour, yes sour, not bitter.

I perform a thanking gesture, while picking up the enormous cup. «Chiara said I could ask you for help: I need to follow the road along the river to get to mount Taurus. Somewhere there my archaeology professor was digging, when…»

«Italian coffee better, right? It’s lemon inside» Fatih explains seeing my suspicious face. He smiles: «No problem, today is Saturday: I go there with you with motorbike».

I accept his help, not before gulping down this sort of hot lemonade that tastes like coffee.

We leave immediately, no helmets on. The motorbike is actually a moped: it doesn’t go faster than 30 km per hour, but even in these conditions, not being the one who drives, makes me feel like on a plane! The road is long and bumpy: I hug tighter the poor driver at every turn; it makes me a little embarrassed, but the fear of being thrown out is bigger. This rough path seems endless, but suddenly Fatih stops: he noticed some panels indicating men at work. We leave the moped and carry on on foot until a sloping height: it is the archaeological site dug by the professor.

Poor Julian: buried in a lonely and forgotten mountain moor, away from the fabulous world he used to reign. Actually, it was not his choice: in sign of spite towards the inhabitants of Antiochia, from where he left on his Persian expedition, he promised himself he would have camped in Tarsus at his return, rather than see the Antiochians again. He didn’t come back alive from that war. His officers, as an extreme form of respect, decided to bury him where he decided to camp that winter: a long, never ending, winter.

The access to the pit is forbidden, it was trenched with a basic barbed wire. A man approaches, he is busy with his hand keeping a huge straw hat on his head. He seems sceptical, but as soon as I mention Luigi Barbarino he lets us in, introducing himself as the professor’s assistant. The sun shines merciless. He shows us to follow him into a sort of warehouse: I can see fragments of ancient vases and animal bones bundled up, but also pots and dirty clothes. In this aluminium roofed and very dusty warehouse, this queer guy, apart from working, also seems to be sleeping and eating.

I would like some information about the incredible finding of the Apostate. With a contrite look on my face, I ask first, with the help of Fatih, news about the professor.

The face of my “interpreter” becomes worried and then grim, after all I did not had the time to tell him about the passing of the “brightest”: «He says that he find dead professor other Saturday, next to… how do you say big descent?»

The assistant claims that last Friday, before leaving, he saw the eminent archaeologist performing land surveys in the pit and that the next morning he found him a little more down that slope, laying on the ground. He had a heart attack and then fell lifeless down the escarpment. The Turkish guy does not seem particularly sad about it, probably because working with the professor left him with the same disgusting sensation as I was. The assistant, a short guy with a fast pace, precedes us on the tragedy site: he really wants us to see the exact place of the finding.

«And that up there, what is it? A tomb?» I ask.

«Yes, he took pictures there. Very important: he found rock with writing on, when it happened» translates Fatih.

Panting I get up the small hill, followed by the other two. I see, crumbled to the floor, what could be the ruins of a funeral building. I cannot see though the epigraph that was supposed to be at the entrance. Only the engraved stone, found by the professor last week (about which he told me via email), could confirm that here lies Julian.

«What about the material you found here?» I ask with fake nonchalance.

«For short time still in the hangar where we were, then comes government officer and takes away everything» Fatih tells me in his uncertain Italian.

I must accelerate.

«I should go to the toilet» I say touching my stomach.

«Only in the warehouse.»

«I know the way, you can stay here, thank you.»

I run to the warehouse and start looking frantically among a pile of crates: I try to move some, they’re heavy. On each one there is a note written with a fading blue marker: these should indicate time and digging sector of the findings.

Which day was it when the professor told me about finding the tomb? I check the crate from 9 July: only pieces of plaster and common pottery. Of course: the discovery must be from the day before, since he sent me the email on the morning of the 9 and died that same evening.

I pull out the crate from 8 July and, I can’t believe it, I find the epigraph!

A marmorean fragment, less than one meter long, with Greeks carvings: I’m in a hurry, but it is hard to understand the letters badly preserved; I take some quick pictures with my inseparable Nikon.

With a flimsy paper that was left on a table and a pencil I improvise a tracing: it is a rudimentary but very efficient technique, learnt during my master in Germany. Rubbing the pencil on the paper put against the epigraph, the holes of the engraved letters leave a blank: all the paper looks grey, apart from the spaces left blank, outlining the shape of the letters.

I’ve lost too much time, I run back to the gloomy cliff: «Sorry… probably the curves of the trip or maybe the violent tale of the professor’s death… well I felt unwell, but I’m better now. So, is the professor here?»

The two look at me confused.

«Well, the corpse: can I take it? I am in charge of taking it back to Italy and…»

«No. It is in the public obituary. I know where it is, I can take there if wants» offers kindly Fatih.

We thank the assistant, who keeps looking at us while going away.

We get back on the moped.

«Gülek Boğazi» screams Fatih short after our departure.

Between the noise of the moped and my fear I can’t understand a thing.

«Gülek Boğazi» he insists, pointing at a canyon among the mountains.

I look down and I understand: it is the “Cilician Gates”, the only passage since ancient times from internal Anatoly and the coast. Crossed by Alexander the Great: a role leader for many, including Julian.

«Gülek Boğazi» I repeat, while the precipice makes me hang even tighter to the driver.

Going down is, as usual, worse than going up: the moped’s breaks seem out of control and at each bend, instead of admiring the landscape, I think about the possibility of falling when right before the cliff it turns and we proceed.

When we arrive at Tarsus’ hospital I am so pale, that they almost take me in as a patient. Fatih asks information to a nurse passing by: I follow my adventure mate, dragging my feet in the long underground corridors until we reach a big ice-cold room.

The anatomopathologist almost invisibly turns up his hooked nose when I show my embassy document. He still lets me sign a series of papers, probably looking forward to getting rid of the corpse. He gets up, gives me two copies of the medical report, then shakes my hand, my arm and then my hand again. Weird way of greeting.

«These documents you give to customs to take body to Italy» translates Fatih, then he adds: «Coffin is outside in the car and with that you go back in Ankara».

I thank him for the translation and all the help, hugging him: I got used to it due to the moped; I try to slip 100 euros in his pocket.

The engineer gets offended: «No… my pleasure, say hi to Chiara, no better, tell her she calls me if she wants. I don’t disturb, but if she… this my number».

«I really don’t know how to thank you, for everything. Greetings to your… mother, as well.»

Outside I find an ambulance: I guess the corpse is in there. I almost got in, when two highly suspicious and huge guys come closer. I try to get away. They follow me and, saying incomprehensible things, push me in front of a shabby white pickup: that’s the designated means of transportation. In open backside I can see the coffin. The two bullies, literally lifting me up, put me there, next to it, while they sit in the front.

The horrible trip of the night before was a joke compared to this one: that one was full of smokers and I had to put my head out, here I am out completely alone with a dead body as company! The coffin, roughly tide with small laces, seems to be jumping out at every hole; I remain holed up on the opposite side: I don’t dare approaching it. I have an absurd fear of finding myself face to face with the corpse: after I left, reluctantly, my job at the University, I never wanted to see again the professor alive, imagine once dead!

I think about the day that’s passed and the one that awaits: the only thought of going back to customs gives me goosebumps, but the task I was assigned from the Literature faculty director is to get back the corpse to Italy. I repeat this mantra to charge myself up along the way, while the wind hits me harsh on the face.

Sunday 18 July

It is around 3 in the morning when the van stops. I’m afraid they want to leave me there, in the middle of nothing.