Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Rosie’s War"

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Copyright © Kay Brellend 2016

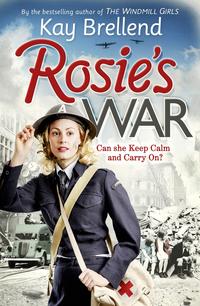

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Photography by Henry Steadman

Other cover photographs © Alamy (children); Shutterstock.com (street scene)

Kay Brellend asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007575305

Ebook Edition © January 2016 ISBN: 9780007575312

Version: 2015-11-03

Dedication

This book is dedicated to all the unsung heroes who served in the London Auxiliary Ambulance Service (LAAS) during the Second World War.

Equally for the volunteers who served in other cities during the conflict.

Not forgotten.

Also, for Mum and Dad.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Kay Brellend

Keep Reading

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

Doctor’s Surgery, Shoreditch, October 1941

‘My mum died young so I’m a bit worried … in case I’ve got the same disease.’ The young woman sat down on the edge of the hard-backed chair. ‘Mum was only thirty-three when she passed away.’

‘You look a lot younger than that and as fit as a fiddle, my dear.’ The doctor raised his wiry grey eyebrows, peering over his spectacles at the exceptionally pretty young woman settling a handbag on her lap. Her platinum hair was in crisp waves and her sea-blue eyes were bright with nervousness. She was nicely dressed and he guessed she had a good job keeping her in such style. He was more used to seeing women with careworn faces, and toddlers on their scruffy skirts, perching nervously at the other side of his desk.

Rosie Gardiner wasn’t sure whether Dr Vernon’s casual dismissal of her concerns had cheered her or left her feeling more anxious. She’d not yet turned twenty and had a healthy glow from a brisk walk on a blustery autumn day. Or the flush could be a fever. In Rosie’s opinion the least he could do was stick a thermometer in her mouth to check her temperature instead of just sitting there tapping his pen on a blotter. Feeling exasperated by his silence she added, ‘It’s hard dragging myself out of bed some mornings. Then I spend an hour bending over the privy out back being sick. It’s not like me to feel too rough to go to work ’cos I like my job at the Windmill Theatre.’

‘Mmm …’ Dr Vernon cast a glance at the young woman’s bare fingers. In wartime women sometimes pawned their jewellery to buy essentials. An absence of an engagement ring didn’t necessarily mean that the lass hadn’t given her fiancé a passionate send-off to the front line, getting herself into trouble in the process.

‘Putting on weight?’ Dr Vernon asked.

‘Not really … no appetite … so I don’t eat much.’

‘Monthlies on time?’

Rosie blushed, wondering why he was asking personal questions like that when she was frantically worried she had the cancer that had put her mother in an early grave. Prudence Gardiner had seemed to be recovering from an operation to remove a tumour but then pleurisy had finished her off. But Rosie had only spotted a little bit of blood instead of proper monthlies.

‘You look to be blooming, my dear … might you be pregnant?’

‘No … I might not!’ Rosie spluttered. ‘I’m not married or even got a sweetheart. I’ve never even wanted to …’

‘Right … I’d better examine you then if there have been no intimate relations to cause trouble.’ Dr Vernon got up from his chair, gesturing for Rosie to stand also. ‘Abdominal fullness, you say, with sickness …’ The muttered comment emerged as he got into position to prod at her with his fingers.

Rosie stayed in her chair, the colour in her complexion fading away. Intimate relations … The phrase hammered in her head and she felt stupid for not having made the connection herself about why her body seemed horribly different. But there had been nothing intimate about that one brutal encounter with a man she’d despised.Rosie’s mind wanted to flinch from the memory but she forced herself to concentrate on the man who’d attacked her all those months ago. Lenny and his father had been her dad’s associates. They’d worked together churning out bottles of rotgut, much to Rosie’s disgust. But what had disgusted her even more was Lenny’s attention. She’d made it plain she’d no intention of going out with him but he wouldn’t take no for an answer. They’d attended the same school, their fathers were friends and Lenny thought that gave him the right to pester her for dates and then call her names when she turned him down. Rosie had hated her father getting involved in crime and had nagged him to break up his illegal booze racket but she hadn’t let on that his association with Lenny was a prime reason for her wanting him to go straight. At that time, she’d been a proud independent woman: a Windmill Girl, and Windmill Girls were able to look after themselves, whether fending off catty theatre colleagues, or randy servicemen lying in wait at the stage door. With youthful arrogance she’d believed she could deal with Lenny herself.

Then one night Rosie had met him by chance in the East End when she was feeling a bit the worse for wear. She’d discovered in just a few vicious minutes that she wasn’t as sassy as she’d thought; she certainly hadn’t been as strong as Lenny, though she’d fought like a maniac to try and stop him.

‘Ah …’ Dr Vernon had seen her stricken look and turned back towards his desk. ‘You’ve remembered an incident, have you, and think there might be reason to count the months after all?’

‘Yes …’ she whispered. ‘But I’m praying you’re wrong, Doctor.’

He smiled kindly. ‘I understand. But better to incubate a life than an illness, my dear.’

Rosie thought about that one. The odd weight she’d sensed in her belly was not a nasty growth in the way she’d thought; but it could destroy her life. ‘If you’re right – and I pray to God you’re not – I think I’d sooner be dead than have his baby,’ she whispered.

CHAPTER ONE

February 1942

‘Well done, dear … good girl … just one more big push. Come on, you can do it …’

Rosie knew that the midwife was being kind and helpful but she just wanted to bawl at her to go away and leave her alone. She had no energy left to whisper a word let alone shout a torrent of abuse. She didn’t want to push, she didn’t want the horrible creature fighting for life in her hips but she knew the agony wouldn’t stop unless she did something … She raised her forehead from the sweat-soaked pillow, dragging her shoulders off the rubber sheeting to grip Nurse Johnson’s outstretched hands. Rosie clung on to the two sturdy palms as tightly as she might have to a piece of driftwood in a raging sea, and gritting her teeth she bore down.

‘What’re you planning on calling her?’

The whispered question emerged tentatively as though the man anticipated a tongue-lashing. And he got it.

‘Calling her?’ Rosie dredged up a weak laugh from her aching abdomen. ‘How about bastard … that should suit. Now go away and leave me alone.’ Rosie turned her pale face to the wall and groaned, drawing up her knees beneath a thin blood-streaked sheet.

The fellow hesitated, then tiptoed about the bed. He knew the poor cow had been driven mad with pain because he’d heard her shrieking even above the din of the wireless. When things had quietened down overhead he’d guessed the worst was over. Then he’d spied the dragon barging down the hall, uniform crackling. As soon as she had disappeared into the front room with a bucket of stuff to burn he’d crept upstairs while the coast was clear.

‘What do you think you’re doing?’ Trudy Johnson burst into the back bedroom and glared at the intruder; childbirth was nothing to do with men, in her opinion. They might put the bun in the oven but should stay well out of the way at the business end of things. The midwife had been disposing of soiled wadding in the parlour fire while waiting for her patient to enter the final stage of labour. But she’d heard voices and speeded up the stairs to see what was going on.

‘I’ve every right to be here.’ John Gardiner sounded huffy. ‘She’s me daughter and that there’s me granddaughter.’ He pointed at the swaddled bundle at the foot of the bed. The infant was emitting mewling squeaks while punching feet and fists into her straitjacket. He almost smiled. The poor little mite was unwanted but she was a fighter. John moved to pick up the newborn but the midwife advanced on him threateningly, fists on starched hips. He backed away, muttering, his hands plunged into his pockets.

‘I think your daughter deserves some privacy, Mr Gardiner. I’ll let you know when she’s ready for a visit.’

Chastened, John trudged meekly onto the landing, then peeped around the bedroom door. ‘Put the kettle on, shall I? Bet you’d like a cuppa, now it’s all over, wouldn’t you, dear?’ He addressed the remark to his exhausted daughter but gave Nurse Johnson a wink when she raised an eyebrow at him.

‘I’d be obliged if you’d make yourself scarce till it is over. But you can put the kettle on. I need some more hot water. Leave a full pot outside the door for me, please.’

Trudy looked at her patient as the door closed. The girl was fidgeting on the protective rubber sheet, making it squeak. The afterbirth was about to be expelled. After that it would be time to set about tidying up the new mum; Trudy hoped having a wash and a brush through her hair might give the poor thing a boost.

Rosie Deane didn’t look more than nineteen and was as slender as a reed. She had battled to get the baby through her narrow hips and finally succeeded after a lengthy labour.

‘Here … have a cuddle … she’s fair like you …’ The midwife placed the baby against Rosie’s shoulder, hoping to distract the young woman from dwelling on her sore nether regions.

‘Take her away from me. I don’t want her.’ Rosie’s hands remained clenched beneath the sheets and she turned her face away from her firstborn.

‘’Course you do; just got a bit of the blues, haven’t you, love? Only natural after what you’ve been through. All new mums say never no more, then quickly forget about the rough side of it.’ Trudy knew that to be true, but not from personal experience. She had no children, but she’d delivered hundreds of babies over more than a decade in midwifery. Some of the women on her rounds in Shoreditch seemed to knock out a kid a year, even into their forties. Mrs Riley, Irish and no stranger to her old man’s fists, had borne fifteen children, twelve of them still alive, and eight of them still at home with her.

Trudy was about to say that the pelvis opened up more easily after a good stretching in a first labour in the hope of cheering up this new mum. Then she realised the remark would be insensitive. The girl’s father had told her that Rosie’s husband had been killed fighting overseas only months ago, so Trudy kept her lip buttoned. In time Rosie would probably remarry and go on to have a brood round her ankles. She was plainly an attractive girl, despite now looking limp and bedraggled after her ordeal.

‘You’ve got a wonderful part of your husband here to cherish.’ Trudy glanced at the child her patient was ignoring. She pushed lank fair hair from Rosie’s eyes so she could get a better view of her baby. ‘See, she’s got her eyes open and is looking at you. She knows you’re her mum all right …’

‘I said take her away from me.’ Rosie levered herself up on an elbow, grabbing at the child as though she might hurl her daughter to the newspaper-strewn floorboards. Instead she held the bundle out on rigidly extended arms. ‘Take her … give her away … do what you like with her …’ she sobbed, sinking down and turning her face into the pillow to dry her cheeks on the cotton.

‘Come on, love; don’t get tearful.’ Trudy placed the baby back by the bed’s wooden footboard then gave her hiccuping patient a brisk, soothing rub on the back. ‘Just a few minutes more and we can give you a nice hot wash down. You’re almost done now, you know.’

‘Almost done?’ Rosie echoed bitterly. ‘I wish I was. It’s all just starting for me, Nurse Johnson …’

CHAPTER TWO

‘You don’t mean that!’

‘If the girl says that’s what she wants to do, then that’s what she wants to do,’ Doris Bellamy stated bluntly. ‘A mother knows what’s best for her own child …’

‘I’ll deal with this,’ John Gardiner rudely interrupted. Doris was his fiancée, and a decent woman. But she wasn’t his daughter’s mother, or his grandkid’s nan, so he reckoned she could mind her own business and leave him to argue with Rosie over the nipper’s future.

‘You won’t change my mind, Dad. I’ve already spoken to Nurse Johnson and she says there are plenty of people ready to give a baby a good home.’

‘Does she now!’ John exploded. ‘Well, I know where that particular baby’ll get a good home ’n’ all. And it’s right here!’ He punched a forefinger at the ceiling. ‘The little mite won’t have to go nowhere. She’s our own flesh and blood and I ain’t treating her like she’s rubbish to be dumped!’

‘She’s not just our flesh and blood, though, is she, Dad?’ Rosie’s voice quavered but she cleared her throat and soldiered determinedly on. ‘She’s tainted by him. I can’t even bear to look at her in case I see his likeness in her.’

‘Forget about him; he’s long gone and can’t hurt you no more.’ John flicked some contemptuous fingers.

‘It’s all right for you!’ Rosie was incensed at her father’s attitude. ‘You just want a pretty toy to show off for a few years till you’re bored of teething and tantrums. You certainly won’t want her around if she turns out anything like that swine.’ Rosie forked agitated fingers into her blonde hair.

‘I think you’d better take that remark back, miss!’ John had leaped up, flinging off Doris’s restraining hand as she tried to drag him back down beside her on the sofa. ‘How dare you accuse me of play-acting? It’s you keeps chopping ’n’ changing yer ideas, my gel.’ John advanced on his daughter, finger wagging in emphasis. ‘I offered at the time to put things right. Soon as we found out about your condition I said I’d stump up to sort it out. Wouldn’t have it, though, would yer? Insisted you was having the baby and was prepared for all the gossip and hardship facing you as an unmarried mother.’ He barked a laugh. ‘Now you want to duck out without even giving it a try.’

‘I said I’d have the kid, not that I’d give it a permanent home,’ Rosie shouted. ‘I’ve got to act before it’s too late: once she gets to know us as her family it wouldn’t be fair to send her away.’

‘It ain’t fair anytime, that’s the point!’ John roared.

‘But … I might never love her. I might even grow to hate her,’ Rosie choked. ‘That’d be wicked because she could have somebody doting on her. She’s not got a clue who we are!’ Rosie surged to her feet at the parlour table, knocking over her mug of tea in the process. Automatically she set about mopping up the spillage with her apron.

She couldn’t deny that some of what her father had said was true. She’d not wanted an abortion; the talk of having something dug out of her had made her retch. The idea of enduring horrible pain and mess had been intolerable; now she knew that the natural way of things was pretty awful too.

Yet Nurse Johnson had been right when she’d said the memory of the ordeal would fade; her daughter was only four weeks old yet already Rosie felt too harassed to dwell on the birth. She guessed every other new mum must feel the same way. But she doubted many of those women were as bitter as she was, and her father, much as he wanted to help, was just making things worse.

‘Cat got yer tongue, has it?’ John was prowling to and fro in front of the unlit fireplace. ‘You should be ashamed. And I ain’t talking about what happened with Lenny. I know that weren’t your fault.’ After a dramatic pause he pointed at the pram. ‘But if you abandon the little ’un you should hang your head, ’cos it should never have come to this.’

‘I’m not a murderer,’ Rosie muttered. ‘I’m not a hypocrite either. Don’t expect me to play happy families.’ Attuned to her daughter’s tiny snickers and snuffles Rosie glanced at the pram. It was an ancient Silver Cross model that her father had got off the rag-and-bone man for a couple of shillings.

He’d brought it home a month before the date of her confinement. The sight of it had shocked and frightened Rosie because up until then she’d shoved to the back of her mind how close she was to having Lenny’s child. John had ignored his daughter’s announcement that he’d wasted his time and money on the pram because the Welfare was getting the kid.

The creaking contraption had been bumped down the cellar stairs and John had toiled on it in his little workshop, as he called the underground room that doubled as their air-raid shelter. Screws had been tightened and springs oiled, then he’d buffed the scratched coachwork and pitted chrome until they gleamed. At present John’s labour of love was wedged behind the settee, with the hood up to give the baby a bit more protection from the chilly March air in the fireless room.

‘She’s gonna be as pretty as you, y’know.’ Taking his daughter’s silence as an encouraging sign, John tried a bit of flattery.

‘Good looks don’t make you happy,’ Rosie stated bluntly. ‘If you force me to keep her, none of us’ll be content.’ She didn’t hate the child: the poor little thing was an innocent caught up in a vile web of violence and deceit.

‘We’ll make sure this is a happy place, dear.’ John sensed his daughter was softening. ‘No point in suffering like you did, then having nothing good to show for it in the end, is there?’

With a sigh, Rosie gathered up their tea things, loading them onto the tray ready to be carried into the kitchenette. She knew it was pointless trying to win over her father. It was always his way or nothing at all. But not this time. She had one final duty to perform before she slipped free of the yoke the poor little nameless mite had fastened around her neck.

She avoided her future stepmother’s eye. Rosie knew that Doris had been watching her, pursed lipped, throughout the shouting match between father and daughter. The woman had resented being told to shut up and had sat in stony silence ever since.

‘Nurse Johnson’s due soon. She said after today it’s time to sign us off home visits.’ Rosie was halfway to the door with the tea tray before adding, ‘I’m going to tell her to start things moving on the adoption.’

‘If you ain’t got the guts to look after her, I’ll do it meself,’ John sounded adamant. ‘No granddaughter of mine’s ending up with strangers, and that’s the end of it.’

Doris leaped to her feet. ‘Now just you hang on a minute there. Reckon I might have something to say about getting landed with kids at my age.’ They’d recently spoken about getting married in the summer so Doris thought she’d every right to have a say.

‘If you don’t like it, you know where the door is.’ John snapped his head at the exit.

Doris gawped at him, her expression indignant. ‘Right then. Couldn’t have made that plainer, could yer?’ She snatched up her handbag, then marched over the threshold and into the hallway.

‘Well, that was bloody daft.’ A moment after the front door was slammed shut, Rosie sighed loudly. ‘If Doris never speaks to you again it’ll be your own fault, Dad.’

‘Don’t care.’ John shrugged. ‘There’s only one person I’m interested in right now.’ He kneeled on the sofa and peered over its threadbare back into the pram. The little girl was sleeping soundly, long fawn lashes curled against translucent pearl-spotted skin. A soft fringe of fluffy fair hair framed her forehead and her tiny upturned nose and rosebud mouth looked as perfectly delicate as painted porcelain.

John stretched out a finger to stroke a silky pink cheek before pulling the blanket up to the infant’s pointed chin. ‘Don’t know you’re born, do you, little angel? But I won’t let you down,’ he promised his granddaughter in a voice wobbling with emotion.

‘You’re just feeling guilty,’ Rosie accused, although she felt quite moved by her father’s melodramatic performance. But what she’d said about him feeling guilty had hit the spot. And they both knew it. A moment later John flung himself past her and the cellar door was crashed shut as he sought sanctuary in his underground den.

Rosie placed the tea tray back on the table. For a moment she stood there, leaning against the wood, the knuckles of her gripping fingers turning white. The baby started to whimper and she automatically went to her. Seated on the sofa she reached a hand backwards to the handle, rocking the pram and avoiding looking at the infant, her chin cupped in a palm. Within a few minutes the room was again quiet. Rosie stood up, drawing her cardigan sleeves down her goose-pimpled arms. She took off her pinafore and folded it, then looked in the coal scuttle, unnecessarily as she knew it would be empty.

It was a cold unwelcoming house for a visitor but it didn’t matter that her father was too thrifty to light the fire till the evening. When Nurse Johnson turned up Rosie intended to say quickly what she had to, then get rid of her so she might start planning her future.

She wandered to the window, peering through the nets for a sighting of the midwife pedalling down the road. It had been many months since she’d hurried from Dr Vernon’s surgery to huddle, crying, in a nearby alleyway. She’d been terrified that day of going home and telling her father the dreadful news that she was almost certainly pregnant, yet he’d taken it better than she had herself. But now, at last, Rosie felt almost content because the prospect of returning to something akin to her old life seemed within her grasp.

Under a year ago she’d been working as a showgirl at the Windmill Theatre. Virtually every waking hour had been crammed with glamour and excitement. She’d enjoyed her job and the companionship of her colleagues, despite the rivalry, but she couldn’t go back there. Her body was different now. Her breasts had lost their pert youthfulness and her belly and hips were flabby. Besides, Rosie felt that chapter of her life had closed and a new one was opening up. Whether she’d wanted to or not, she’d grown up. The teenage vamp who’d revelled in having lavish compliments while flirting with the servicemen who flocked to the shows, no longer existed. Wistfully Rosie acknowledged that she’d not had a chance to kiss goodbye to that sunny side of her character. That choice, and her virginity, had been brutally stolen from her by Lenny, damn the bastard to hell …

But once her daughter was adopted Rosie knew she’d find work again, and she wanted her own place. Her father’s future wife resented her being around and Rosie knew she’d probably feel the same if she were in Doris’s shoes.

Suddenly she snapped out of her daydream, having spotted Nurse Johnson’s dark cap at the end of the street. Rosie let the curtain fall and pulled the pram out from behind the sofa so the midwife could examine the baby. Although she was expecting it, the ratatat startled her. Rosie brushed herself down then quickly went to open the door, praying that her father wouldn’t reappear to embarrass her by making snide comments.

Half an hour later the examinations were over and Rosie was sitting comfortably in the front parlour with the midwife.

‘She’s a beautiful child but would benefit from breast milk rather than a bottle, Mrs Deane. She might put on a bit more weight.’

Rosie smiled weakly; she hated people calling her by the wrong name. Her father and Doris had persuaded her to pass herself off as a war widow to stop tongues wagging. But that hadn’t worked: the old biddies were still having a field day at her expense. Rosie had chosen to use her mother’s maiden name as her pretend married name. She cleared her throat. ‘What we spoke about last time, Nurse Johnson …’

Trudy Johnson put down her pen on the chart she’d been filling in. ‘You still want to have her adopted?’ she prompted when Rosie seemed stuck for words.

‘I do … yes …’

‘Why? You seem to be coping well, and you have your father’s support.’

‘I’m not married,’ Rosie blurted, although she was sure the midwife had already guessed the truth. ‘That is … I’m not widowed either … I’ve never had a husband.’

Trudy sat back in the chair. It wasn’t surprising news, but Rosie’s honesty had taken her aback. Families who were frightened of ostracism often came up with non-existent husbands to prevent a daughter’s shame tainting them all. And now it was clearer why the baby still hadn’t been named. Much of the falsehood surrounding illegitimate births unravelled when awkward questions were asked at the registry office.

‘I guessed perhaps that might be the case.’

‘You don’t know the ins and outs of it all.’ Rosie bristled at the older woman’s tone. ‘Nobody does except me and Dad.’

Trudy Johnson could have barked a laugh at that. Instead she put away her notes in the satchel at her feet. At least this young woman had had the guts to go through with it, whereas lots of desperate girls allowed a backstreet butcher to rip at their insides. She had been approached herself over the years by more than one distraught family to terminate a ‘problem’ for them. Trudy had always refused to abort a woman’s baby but it didn’t stop them going elsewhere. And, to Trudy’s knowledge, at least two of those youngsters had ended up in the cemetery because of it.

‘Your situation’s more common than you think.’ Again Trudy’s tone was brisk. ‘Unlike you, though, I’ve seen some poor souls turfed out onto the streets with their babies. Your father is keeping a roof over your heads.’

‘It’s the least he can do, considering …’ Rosie bit her lip; she’d said enough. Besides, she didn’t want to get sidetracked from the important task of finding her daughter a new home.

Trudy stood up, buckling her mac, and gazed into the pram. The baby was awake. She’d been just five pounds at birth and was struggling to put on weight. Arms and legs barely bigger than Trudy’s thumbs were quivering and jerking, and just a hint of a smile was lifting a corner of the little girl’s mouth. It was probably wind but Trudy tickled the adorable infant under the chin.

‘I want her adopted,’ Rosie stated firmly. ‘And I want it done soon, before she gets attached to us.’

‘If you’re sure that’s what you want to do, then I’ll have her. I’ve never been married but I’ve always wanted a child.’ Trudy sent Rosie a sideways smile. ‘I almost got married when I was seventeen but …’ She shrugged. Her memories of Tony were too precious to share. She even avoided talking about her dead lover with her elderly parents. They’d liked him, and had mourned his passing almost as much as she had herself.