Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

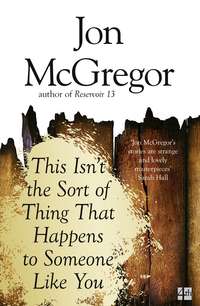

Buch lesen: "This Isn’t the Sort of Thing That Happens to Someone Like You"

This Isn’t the

Sort of Thing

That Happens

to Someone

Like You

Jon McGregor

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by Bloomsbury in 2012

This eBook published by 4th Estate in 2017

Copyright © 2012 by Jon McGregor

Linocuts © 2012 by Paul Greeno

Cover image © Shutterstock

Jon McGregor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008218652

Ebook Edition © January 2017 ISBN: 9780008218669

Version: 2016-12-07

Praise for This Isn't The Sort Of Thing That Happens To Someone Like You

‘Jon McGregor is one of the UK’s most fascinating and versatile writers’ Gary Shteyngart, author of Super Sad True Love Story

‘Jon McGregor’s writing combines dreamy, ethereal poetry with a northern sensibility unafraid to confront devastating truths … McGregor is adept at depicting emotions with unassuming language’ Independent

‘These unnerving splinters depicting ordinary people in crisis, often against the fathomless landscape of the Fens, make for an outstanding collection from a great writer’ Metro

‘This is a book of ominous preludes and chilling aftermaths: the incantatory account of a vacationer at a war-ravaged resort in the minutes before he drowns; the Pinter-esque power play of a vicar’s wife whose husband offers shelter to a gallingly manipulative stranger. McGregor stealthily commands our active engagement, scattering crumbs of data for us to pick through, gum-shoe style’ New York Times

‘Electrifyingly original and skilful … McGregor also has a gift for lyricism and shows great skill and fearlessness in his experiments with form. I can’t remember the last time I read a collection of stories this original, this strange, or this powerfully menacing’ Sydney Morning Herald

‘[E]ach tale in this slim, elegant book does something most of us wish would happen to us in real life: It stops us in a humdrum moment and reveals how that small, unnoticed sliver of time can illuminate an entire life’ Oprah.com Book of the Week

‘Jon McGregor’s stories are strange and lovely masterpieces: painfully authentic, inquisitive rather than confrontational, he has a tremendous ability to disturb the surface of everyday things ... Underneath that which is radically quotidian, he captures our unique and unusual selves’ Sarah Hall

For Éireann Lorsung,

& Matthew Welton

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for This Isn’t the Sort of Thing That Happens to Someone Like You

Dedication

PART ONE

That Colour

In Winter The Sky

She Was Looking For This Coat

Looking Up Vagina

Keeping Watch Over The Sheep

Airshow

We Were Just Driving Around

PART TWO

If It Keeps On Raining

Fleeing Complexity

Vessel

Which Reminded Her, Later

The Chicken And The Egg

New York

PART THREE

French Tea

Close

We Wave And Call

PART FOUR

Supplementary Notes To The Testimony Of Appellants B & E

Thoughtful

The Singing

Wires

What Happened to Mr Davison

Years Of This, Now

The Remains

PART FIVE

The Cleaning

The Last Ditch

Dig A Hole

I Remember There Was A Hill

Song

I’ll Buy You A Shovel

PART SIX

Memorial Stone

Acknowledgements

Read an exclusive extract from Jon McGregor’s new novel, Reservoir 13

By the Same Author

A Note on the Author

About the Publisher

Back to contents page

That Colour

Horncastle

She stood by the window and said, Those trees are turning that beautiful colour again. Is that right, I asked. I was at the back of the house, in the kitchen. I was doing the dishes. The water wasn’t hot enough. She said, I don’t know what colour you’d call it. These were the trees on the other side of the road she was talking about, across the junction. It’s a wonder they do so well where they are, with the traffic. I don’t know what they are. Some kind of maple or sycamore, perhaps. This happens every year and she always seems taken by surprise. These years get shorter every year. She said, I could look at them all day, I really could. I rested my hands in the water and I listened to her standing there. Her breathing. She didn’t say anything. She kept standing there. I emptied the bowl and refilled it with hot water. The room was cold, and the steam poured out of the water and off the dishes. I could feel it on my face. She said, They’re not just red, that’s not it, is it now. I rinsed off the frying pan and ran my fingers around it to check for grease. My knuckles were starting to ache again, already. She said, When you close your eyes on a sunny day, it’s a bit like that colour. Her voice was very quiet. I stood still and listened. She said, It’s hard to describe. A lorry went past and the whole house shook with it and I heard her step away from the window, the way she does. I asked why she was so surprised. I told her it was autumn, it was what happened: the days get shorter, the chlorophyll breaks down, the leaves turn a different colour. I told her she went through this every year. She said, It’s just lovely, they’re lovely, that’s all, you don’t have to. I finished the dishes and poured out the water and rinsed the bowl. There was a very red skirt she used to wear, when we were young. She dyed her hair to match it once and some people in the town were moved to comment. Flame-red, she called it then. Perhaps these leaves were like that, the ones she was trying to describe. I dried my hands and went through to the front room and stood beside her. I felt for her hand and held it. I said, But tell me again.

In Winter The Sky

Upwell

He had something to tell her. He announced this the next day, after the fog had cleared, while the floods still lay over the fields. It looked like a difficult thing for him to say. His hands were shaking. She asked him if it couldn’t wait until after she’d done some work, and he said that there was always something else to do, some other reason to wait and to not talk. All right, she said. Fine. Bring the dogs. They gave his father some lunch, and they walked out together along the path beside the drainage canal.

She knew what he wanted to tell her, but she didn’t know what he would say.

What she knew about him when she was seventeen: he lived at the very end of the school-bus route; he was planning to go to agricultural college when he finished his A levels; he didn’t talk much; he had nice hair; he didn’t have a girlfriend.

What she knew about him now: he didn’t talk much; he had a bald patch which he refused to protect from the sun; he didn’t read; he was a careful driver; he trimmed his toenails by hand, in bed; he often forgot to remove his boots when coming into the house; he said he still loved her.

He was seventeen the first time he kissed a girl. The girl had long dark hair, and brown eyes, and chapped lips. They sank low in their seats on the school bus, leaning together, and she took his face in her hands and pushed her mouth on to his. She seemed to know what she was doing, he said later. He was wrong. She drew away just as he was beginning to get a sense of what he’d been missing, and said that she’d like to see him again that same evening. If he wasn’t busy. They should go somewhere, she said, do something. He didn’t ask where, or what. She got off the bus without saying anything else, and went into her house without looking back. She ran upstairs to her bedroom, and watched the bus move slowly towards the horizon, and wrote about the boy in her notebook.

Leaving March, where she lived then, the school bus passed through Wimblington before swinging round to follow the B1098, parallel to Sixteen Foot Drain, until it stopped near Upwell. It was a journey he made every day, from the school where he was studying for his A levels to his father’s house where he helped on the farm in the evenings. Where the two of them run the farm together now. The road beside the Sixteen Foot is perfectly straight, lifted just above the level of the fields, and looking out of the window that afternoon felt, he said later, in a phrase she noted down, like he was passing through the sky.

The girl’s name was Joanna. The boy’s name was George. He came back for her the same night.

He has told her this part of the story many times, with the well-rehearsed air of a story being prepared for the grandchildren: how he waited until his father was asleep before taking the car-keys from the kitchen drawer, that he’d driven before, pulling trailers along farm tracks, but he didn’t have a licence and his father would never have given him permission, how he remembered that she’d said she wanted to see him, to go somewhere and do something, that he knew he couldn’t just sit there in that silent house, doing his homework and listening to the weather forecast and getting ready for bed.

She wonders, now, what would have been different if he had stayed home that night. She wants to know how he thinks he would feel, if that were the case. An impossible question, really.

The roads were empty and straight, and there was enough moonlight to steer by. She saw him coming from a long way off. Watching his headlights as they swung around the corners and pointed the way towards her. She was waiting outside by the time he got there.

She hadn’t wanted to go anywhere in particular. She just wanted to sit beside him in the car and drive through the flatness of the landscape, looking down across the fields from the elevated roads. They drove from her house to Westry, over Twenty Foot Drain, past Whittlesey, and as they passed through Pondersbridge she put her hand on his thigh and kissed his ear. They crossed Forty Foot Bridge and drove through Ticks Moor, the windows open to the damp rich smell of a summer night in the fens, and beside West Moor he put his hand into her hair. They crossed the Old Bedford and New Bedford rivers, drove through Ten Mile Bank, Salter’s Lode and Outwell, and on the edge of Friday Bridge she asked him to stop the car and they kissed for a long time.

Afterwards, they looked out across the fields and talked. They didn’t know each other very well, then. He asked about her family and she asked about his. He told her about his mother, and she said she was sorry. She asked what he was going to do when he left school and he said he didn’t know. He asked her the same and she said she wanted to write but that her father wanted her to go to agricultural college. She lifted his thin woollen jumper over his head and drew shapes on his bare skin with the sharp edge of her fingernail. She watched as he undid the buttons of her blouse. She took his hands and placed them against her breasts. There was the touch of her whisper in his ear, and the taste of his mouth, and the feel of his warm skin against hers, and the way his scalp moved when she pulled at his hair. Later, there was the smell of him on her hands as she stood outside her house and watched him drive away in his father’s car, the two red lights getting smaller and smaller but never quite fading from view in the dark, flat land.

He drove home along the straight road beside the Sixteen Foot, holding his hand to his chest. The moonlight shining off the narrow water. He was thinking about all the things she’d said, just as she was thinking about all the things he’d said.

He was thinking about his father, he said later, and about how long his father had been alone, and about how he knew now that he wouldn’t be able to live on his own in the same way. Not now he knew what it meant to be with someone else. He was still thinking about her when he drove into a man and killed him.

First he was driving along the empty road thinking about her, and then there was a man in the road looking over his shoulder and the car was driving into him. It was hard to know where he’d come from. He’d come from nowhere. He was not there and then he was there and there was no time to do anything. There was no time to flinch, or to shout. He didn’t even have time to move his hand from his chest, and as the car hit the man he was flung forwards and his hand was crushed against the steering wheel. The man’s arms lifted up to the sky and his back arched over the bonnet and his legs slid under one of the wheels and his whole body was dragged down to the road and out of sight.

Those arms lifted up to the sky, that arching back.

The sound the man’s body made when the car struck him. It was too loud, too firm, it sounded like a car driving into a fence rather than a man. And the sound he made. That muffled split-second of calling-out.

His arms lifted up to the sky, even his fingers pointing upwards, as if there was something he could reach up there to pull himself clear. His back arching over the bonnet of the car before being dragged down. The jolt as he was lost beneath the wheels. George’s hand crushed between his chest and the steering wheel.

Then stillness and quiet.

He lay on his back with his legs underneath him, looking up at the night. His legs were bent back so far that they must have been broken. George stood by the car for a long time. The man didn’t make a sound. There was no sound anywhere. The night was quiet and the moon bright and the air still and there was a man lying in the road a few yards away. It didn’t feel real, and there were times now when they both wondered whether it had really happened at all. But there was the way the man’s neck felt when George touched his fingers against the vein there. Not cold, but not warm either, not warm enough: he feels like a still-born calf. There was no pulse to feel. Only his broken body on the tarmac, his eyes, his open mouth.

He was wearing a white shirt, a red V-necked jumper, a frayed tweed jacket. His arms were up beside his head, and his fists were tightly clenched. A broken half-bottle of whisky was hanging from the pocket of his jacket. There didn’t seem to be any blood anywhere; there were dirty black bruises on his face, which might have been old bruises anyway, but there was no blood. His clothes were ripped across the chest, but there was no blood. It was hard to understand how a man could be dragged under the wheels of a car and not bleed. It was hard to understand how he could not bleed and yet die so quickly.

The whites of his eyes looked yellow under the moonlight.

It was hard to understand who he was, and why he had been on the road in the middle of the night. Why he was dead now. It was hard to know what to do. George knelt beside him, looking out across the fields, up at the sky, at his father’s car, his shaking hands, the sky.

He had his reasons, he says. He’s often regretted it, and he’s often thought that his reasons weren’t enough, but he thinks he would do the same again.

If he’d been older when he made that journey then perhaps he would have been stronger; perhaps his thoughts would have been clearer. But he was seventeen, and he had never knelt beside a dead man before. So he drove away. He stood up, and turned away from the man, and walked back to his father’s car, and drove away. He didn’t look in the rear-view mirror, and he didn’t turn around when he slowed for the junction.

I suppose it was at that stage that I began to realise what had happened what I had done.

That was how he put it, when he told her, walking out on the path beside the canal after lunch, the dogs running along ahead of them with their claws clicking on the tarmac strip. I suppose.

He had driven his father’s car into a man, and then over him, and now that man was dead. He felt a sort of sickness, a watery dread, starting somewhere down in his guts and rising to the back of his throat. His hands were locked on the wheel. He couldn’t even blink.

And he knew, even before he got back to his father’s house, that he would have to return to the man. He couldn’t leave him laid out on the road like that, with his legs neatly folded under his back. He knew, or he thought he knew, that when the man was found then somehow he would be found too, and the girl who’d drawn upon his bare chest wouldn’t even look him in the eye.

So it was her fault as well, it seems.

He fetched a shovel from a barn at his father’s farm and drove back to where he’d hit the man. It sounds so terrible now. Cowardly? He carried the shovel down the embankment to the field below the road and took off his jumper and began to dig.

He was used to digging. The field had only recently been harvested, and the stubble was still in the ground, so he lay sections of topsoil to one side to be replaced. He was thinking clearly, working quickly but properly, ignoring the purpose of the hole. Once, knee-deep in the ground, he looked up the bank and realised what he was doing. But he couldn’t see the man up on the road, so he managed to swallow the rising sickness and dig some more. And all this time, the sound of metal on soil, the sky above.

And then it was deep enough. It was done. So long as it was further beneath the surface than the plough-blades would reach then it was deep enough, most probably. He climbed up the embankment to the road, wanting to hurry and get it done but holding back from what he had to do, from the fact of having to touch him, having to pick him up and carry him down the bank and into the hole he had made. The death he had made in the hole he had made in the earth. He bent down to take the man’s arms. He could smell whisky. He stopped, unwilling to touch him, unwilling to go through with what he’d found reason to do. They were good reasons, but they didn’t seem enough. But then he remembered her skin on his, and her eyes, and he knew, he said, that he could do anything not to lose that.

She’d made him do it, then. That was how it had happened.

He gripped the man’s elbows and lifted them up to his waist. He backed away towards the embankment and the man’s legs unfolded from beneath him, his head rolling down into his armpit, his half-bottle of whisky falling from his pocket and breaking on the road. He didn’t stop. He kept dragging him away, away from the road, down the bank, into the field.

She’d said, when he finally told her all this, that she wanted to know it all. How it was done. How it had felt. So now she knew.

He laid the man down beside the hole in the earth and rolled him into it. The man fell face down, and he felt bad about that, about the man’s face being in the mud. He went back to the place on the road and picked up the pieces of glass. He threw them down on to the man’s back, and then he took the shovel and began to pile the earth back into the hole.

He threw soil over the man until he was gone, until the soil pressed down on him so that he was no longer a man or a body or a victim or anything. Just an absence, hidden under the ground. It was only then that he looked up at the sky, dark and silent over him, the moon hidden by a cloud. He drove past her house in March again, and then back to his father’s house. He put the car-keys away in the kitchen drawer, and the shovel in the barn, and he stood in the shower until the hot-water tank had emptied and he was left standing beneath a trickle of water as cold as stone.

So now she knew.

They were married before either of them had the chance to go to university: his father retired early, after a heart attack, and he had to take over the farm. It only made sense for Joanna to move in and help. George had been there when his father collapsed: he’d heard the dogs barking at the tractor in the yard, and gone outside to see his father clutching at his chest and turning pale. He’d dragged him from the cab into the mud and begun hammering on his chest. I didn’t want to lose him to the land as well. He’d beaten his father’s heart with his fist, and forced air into his lungs, and called out for help. She was there with him. She rang the ambulance, and watched him save his father’s life, and decided she would marry him. She can remember very clearly, standing there and deciding that. And he still thinks he was the one who asked her.

When she remembers it now, it’s always from a height, as if she can see it the way the sky saw it: George kneeling over his father in the mud of the yard, shouting at him to hold on, the dogs circling and barking.

And now this giant of a man sits in an armchair clutching a hot-water bottle and watching the sky change colour outside. He refuses to watch television, listening instead to the radio while he keeps watch on the land and the sky. He claims to take no interest in the running of the farm: he signed everything over to them almost immediately, and has rarely offered an opinion. But she knows that he watches. She has seen him looking at a newly ploughed field from the upstairs window, or running a hand along a piece of machinery in the yard, or lingering by the kitchen table while she does the accounts. She has seen the faint smiles and nods which indicate that he is well pleased. She hopes that George has noticed; she suspects that he has not. Sometimes, when George takes his father his evening meal, his father will talk about something he’s heard on the radio: a concert recording, a weather forecast, a news report. Often they’ll just sit, and George will listen to his father’s short creaking breaths, thankful to have him there still. She doesn’t sit with them at these times. She reads, or deals with paperwork, or goes back to her writing, waiting for him to reassure himself that his father is well.

They’ve never had children, and this has

They’ve never talked about it, and yet

In this way, their lives together had settled into something like a routine. He was up first, feeding the dogs, bringing her a cup of tea, eating his breakfast and leaving his dishes on the table. She dressed, and ate her breakfast, and cleared the table, and waited until she heard the radio in his father’s bedroom before going to help him dress.

Caring for his father had taken up more and more of their time over the years. His health was poor enough to justify moving him into a nursing home. There was one over in March; she had a friend whose mother was there, and had heard good reports. But it was obvious that his father would refuse to go. And she had been unable to find a way of bringing it up with George. There were so many things she was unable to bring up with him. Sometimes it felt as though they only related to each other through talking about work, about the business. As business partners, they have been close, communicative, collaborative. All those good words.

In the mornings and the afternoons, they worked in the fields. That wasn’t really true. It might have been true once, in the very early days, when they’d had to work hard all the hours of daylight to try and pull the business out of the hole his father had dug it into. There’d been no money to employ extra labour, and they’d had to do everything themselves. There was less land then, but it was still a struggle and they were always exhausted by the time they found their way to bed.

But things had changed, gradually. They’d bought more land, secured more grants and loans. Diversified. And almost without noticing, they’d stopped being farmers and become managers. Most of the field-work was done by labourers hired by sub-contractors, people they never spoke to. George still liked to do some of the work himself – the ploughing, the ditch-digging, the heavy machine-based jobs – but there was no real need. For the most part they spent their days on the phone, or filling out forms, buying supplies, dealing with inspectors, negotiating with the water authorities. Discussions about drainage and flood defences seemed to take more and more of her time now. The floods seemed to be coming more often, covering more land, taking longer to drain. Maybe we should switch to rice, George had started saying, and she wasn’t sure whether or not this was a joke.

All of which meant that when he said he wanted to tell her something, and that they should take the time to walk out along the path beside the canal after lunch, it was no real interruption to the running of the farm. Down in the few fields which weren’t yet flooded, the workers carried on, their backs bent low, and she was able to stop him and put her hand to his chest and ask what it was he wanted to say.

In the evenings he often spent time in the barn, fixing things. She would spend that time walking backwards and forwards from the house to the barn, offering to help, and having that help warmly but firmly rejected. He was unable to admit, even now, that she was better than he was at mechanical jobs: repair, maintenance, improvised alteration and the like. Her father had been a mechanic. It was natural that she would have an ability in that area. But still, he found it difficult to accept.

At the same time, he found it difficult to have sufficient patience with, or tolerance of, the writing she did. She had only ever called it writing: he was the one who used the word ‘poems’. But whenever he said it – ‘poems’ – it was with an affected air, as if the pretension was hers. So, for example, he might come crashing in from the barn late one afternoon, with his boots on, and say Would you just leave your bloody poems alone for one minute and help me get the seed-drill loaded up? There were five other places he could have put the bloody in that sentence, but he chose to put it there, next to ‘poems’. This is an example, she would tell him, if he was interested, of what placement could do.

Once, he says, he saw a man metal-detecting in that field. He was driving past and saw a car parked on the verge, a faint line of footprints leading out across the soil. The light was clear and strong, and the man in the field was no more than a silhouette. He sat in his car, watching. Twice he saw the man stoop to the ground and dig with a small shovel. Twice he saw him stand and kick the earth back into place, and continue his steady sweeping with the metal detector. He wanted to go and tell him to stop, but there was no good reason for doing so. It wasn’t his land. The man would surely have asked permission, and anyway he was doing no damage so soon after harvest.

He wondered what the man thought he was going to find, he says. He had a sudden feeling of inevitability; that this would be the moment when the body was found, the moment when everything could be made right. He thought about going to fetch Joanna, so she could be there to see it as well.

He’d been living like this for years, it would seem, lurching between a trembling silence and a barely withheld confessional urge. When he thought about it later, he realised there was no reason why a man with a metal detector should find a body. But that kind of logical thought seemed to crumble in the face of these moments.

He got out of the car, and waited. The man in the field looked up at George, and George looked down at him. Ready. The man packed his tools into a bag and began hurrying back to his car, stumbling slightly across the low stubble.

Did you find anything? George asked.

No, the man said, nothing. And he got in his car and drove away.

This is the way it happens, in the end. This is the way he describes it, when he tells her:

He was driving, he said. There were bright lights, and men in white overalls standing in the water. There were police officers along the embankment and a white tent on the verge. There were police vans in the road. A policeman was directing the traffic through from either direction. The men in white overalls were doing something with poles and tape. He could hardly breathe, he said. There was something like a rushing sound in his ears.

The policeman waved at him to stop, and walked over to the car, and asked George to wind the window down. He reminded George that they were at school together, and George didn’t know what to say. A funny do this, isn’t it, the policeman said. George thought the policeman was probably waiting for him to ask what had happened but he didn’t say anything. The policeman told him anyway: they’d found a body in the water. The farmer had seen it. They were assuming it had been buried for years, and that the flood water must have disturbed the soil and brought it out. There wasn’t much left of it now. The policeman said he couldn’t imagine they’d find out who it was, and then he asked after the family and said he should let George get on. George said that his wife and his father were both fine and drove slowly into the fog.

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.