Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

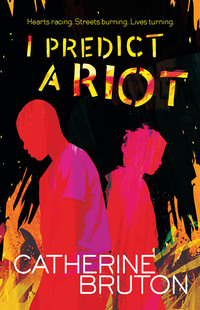

Buch lesen: "I Predict a Riot"

First published in Great Britain 2014

by Electric Monkey, an imprint of Egmont UK Limited

The Yellow Building, 1 Nicholas Road, London W11 4AN

Text copyright © Catherine Bruton 2014

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978 1 4052 6719 9

eISBN 978 1 7803 1345 0

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at the time of going to print. However, Egmont is not responsible for content hosted by third parties.

Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are supervised when using the internet.

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons – living or dead – is purely coincidental.

EGMONT

Our story began over a century ago, when seventeen-year-old Egmont Harald Petersen found a coin in the street. He was on his way to buy a flyswatter, a small hand-operated printing machine that he then set up in his tiny apartment.

The coin brought him such good luck that today Egmont has offices in over 30 countries around the world. And that lucky coin is still kept at the company’s head offices in Denmark.

For all my Peckham people, Clare, Howard, Nye, Nicola, James, Jo, Millie, Jonny, Joe and Elsie the Twinkle, with love.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title page

Copyright

Dedication

SCENE 1: MAGGIE’S HOUSE, BY THE SEA

SCENE 2: A PARK IN SOUTH LONDON

SCENE 3: CORONATION ROAD LIBRARY

SCENE 4: OUTSIDE THE LIBRARY

SCENE 5: CORONATION ROAD

SCENE 6: BEHIND THE FISH FACTORY

SCENE 7: MAGGIE’S HOUSE

SCENE 8: OUTSIDE MAGGIE’S BEDROOM

SCENE 9: THE NEXT MORNING. CHOUDHARY’S ELECTRICAL STORE

SCENE 10: MAGGIE’S DEN

SCENE 11: OUTSIDE THE STARFISH PROJECT

SCENE 12: CORONATION ROAD

SCENE 13: OUTSIDE THE PICTURE GALLERY

SCENE 14: MAGGIE’S BEDROOM

SCENE 15: MAGGIE’S DEN

SCENE 16: THE LOUNGE IN MAGGIE’S HOUSE

SCENE 17: TOKES’S BEDSIT

SCENE 18: CORONATION ROAD

SCENE 19: CORONATION ROAD. DUSK

SCENE 20: CORONATION ROAD. EVENING

SCENE 21: CORONATION ROAD. THE NEXT DAY

SCENE 22: THE LOUNGE IN MAGGIE’S HOUSE

SCENE 23: BEHIND THE FISH FACTORY

SCENE 24: THE PARK

SCENE 25: THE PARK. MOMENTS LATER

SCENE 26: THE PARK, A FEW MINUTES LATER

SCENE 27: A HOUSE BY THE SEA. ONE YEAR LATER

SCENE 28: THE BEACH

Acknowledgements

Praise for We Can be Heroes and Pop!, also by Catherine Bruton

Books by Catherine Bruton

SCENE 1: MAGGIE’S HOUSE, BY THE SEA

It’s been a year since everything happened, but I still have bad dreams. Dreams of last summer – of me and Tokes and Little Pea – in the park, under the arches, racing through burning streets on the night the city was in flames. It’s like a movie running through my head – the same one night after night. Then I wake up to the sound of the waves and I remember how the story ends.

We live by the sea now, my mum and me. In a house with a long garden that runs down to a pebbly beach, far away from where it all happened. I can see the water from my bedroom window, hear the waves lapping on the pebbles. And there’s nothing to do here but remember how one of my friends is dead and the other one might as well be. All because of me.

I think he has a new name now which would make Little Pea laugh because he always reckoned it was a stupid name. He’s got a whole new identity too: new home, new life – new start. A witness-protection programme. The police had to make him and his whole family disappear so Shiv and the Starfish Gang would never find them. And that means they can’t tell me where he is and I can never contact him. Ever. No phone, no text, no email, no Facebook. Nothing. It’s for his own safety, I suppose, but he probably never wants to see or speak to me again anyway.

Most days I watch the film we made last summer. I’ve had a long time to try and finish it, but it still feels like something is missing. Even though I’ve cut and edited bits, changed angles, altered the soundtrack, I can’t ever seem to change the story it tells. Just like in my dreams.

SCENE 2: A PARK IN SOUTH LONDON

‘The boys are back in town!’ Little Pea was singing.

All the other kids in the park had gone silent. Little Pea was perched on one of the kiddie swings like some kind of weird boy-bird, staring in the direction of the approaching Starfish Gang who were obviously going to beat him to a squishy pulp. But he kept on singing like a canary in a cage.

He knew what was coming. I’d zoomed in so the lens of my camera was staring right into his pupils. If you ask any film director, they’ll tell you it’s all in the eyes and, even though Little Pea had this massive crazy smile spread over his funny baby face as he sang, you could tell from his eyes that he knew he was in for a beating.

If this had been a proper film, it would be a gangster movie or maybe a Western. There’d be whistling wind in the background, or the strumming of a lone guitar as the baddies walked into view across the horizon while the little guy trembled and prayed for the hero to ride in and rescue him. Only there was no hero coming to rescue Little Pea from what I could see. Because real life isn’t like the movies, is it? That’s what my mum’s always saying anyway.

I was perched in the middle of the roundabout, cross-legged, filming everything, but trying to pretend my camera was just a mobile phone so nobody would realise. I think I knew that if the Starfish Gang caught me they’d smash my camera – and probably me too. But I thought I was invisible in those days. Invisible and safe. I was wrong on both counts.

Little Pea was acting like he wasn’t worried either. ‘The boys are back! The boys are back!’ he squawked, high-pitched, bird-like, kind of out of tune.

Little Pea was in Year 8 so I suppose that made him about twelve, but he looked no bigger than a nine-year-old. I’d heard someone say he was a fully-grown adult midget; and another who reckoned his mum had been poisoning him and stunted his growth. I’d even heard a rumour that he was an alien or that he’d been abducted by aliens who’d shrunk him on their spaceship! There were a lot of rumours about Little Pea.

Pea wasn’t his real name either, but it kind of suited him because he had this small round face and eyes that looked kind of green in the light, although they were twinkling with what looked like fear now as he stared in the direction of the Starfish Gang.

With my camera perched on my knee, I could catch their shadows as they walked across the concrete, and the white clouds scudding across the high-rise flats behind them. It made them look like they were walking in slow motion. Or maybe that was something they did – another trick to make themselves seem even scarier. Like everyone in the neighbourhood wasn’t scared enough of them already.

No one messed with the Starfish Gang. Even I knew that, and I wasn’t even from around there. Not really. I knew about the drug raps, the robberies, the street wars and stabbings and shootings. And about the army of local kids they had running errands for them all over town. Rumour had it that Shiv, the gang leader, stabbed some kid over in North London, and that Tad, his number two, carried a gun shoved down his left sock.

How did I know? Because I watched and I listened. That’s something all the great film directors do. I read it in an interview in a film magazine: you have to sit in cafes and bus stops and parks and listen to people, find stories. There are stories all around you, all the time, it said. Stories waiting to be told.

So that’s what I used to do, ever since my mum and dad split up anyway. My mum said I needed to stop filming other people’s lives and live my own, but she didn’t get it. That was exactly why I did it: to escape into other people’s stories so I didn’t have to think about my own rubbish life at all.

That day the Starfish Gang strode across the park like they owned it, their jeans hanging so low you could see pretty much all of their boxer shorts, their baseball caps resting on the top of their heads like they were far too small. And at the front was Shiv, the gang leader, skinny like a snake with a face the colour of storm clouds, wearing this long black leather coat that flapped round his ankles. It made him look like a vampire.

He had marks on his cheeks, symmetrical half-moon scars, mirror images below the whites of his pale milky eyes. I think I’d heard someone say he was only seventeen, but his eyes glared like his insides were rotting away in his belly. It made you wonder what he’d seen to make him look that way. Or what he’d done.

He came to a stop about five metres short of the swings and the rest of the gang stopped behind him. Little Pea was still chirruping away. Shiv just stood there and stared at him – totally still, like you see lions doing on those wildlife programmes when they’re about to pounce. There was a pause – it’s just a couple of beats when you watch it back on film – before Pea stopped singing and fluttered down off the swing. He was grinning as if he was their puppy dog, but I caught a glimpse of his eyes and they were bright as buttons and blinking like mad.

‘Whatcha, Shiv?’ he chirped. He was doing a funny dance thing, like a cross between Riverdance and body-popping, and grinning nervously.

Shiv stayed silent. From the railway track that runs alongside the park came a distant ringing: that sound the rails make when a train is coming close.

‘Whassup, Shiv-man?’ Pea squeaked. ‘What can I do for you, my main man, eh?’ He was doing a moonwalk on the hot concrete now, in a pair of dirty white trainers with a Nike tick drawn on in pen.

‘You, blud!’ Shiv hissed. He took a step forward and Pea stopped dancing. ‘You’re whassup!’

‘Why? What I done?’ said Little Pea, mouth still grinning, but his eyes flicking from side to side.

‘You know what you done,’ Shiv said, taking another step forward. Pea darted backwards, tripping up over his feet. His fake trainers looked weirdly big for his tiny body.

‘My cousin Pats got a beating cos of you, boy!’ Shiv went on, tipping his head to one side and staring so hard at Pea he looked like he could pin him up against the fence just with his eyes.

‘Hey, no way, Shiv-man!’ Pea protested, wriggling backwards some more. ‘I wasn’t even there when it happen, bro!’

‘Ex-act-ly!’ said Shiv, spitting out each syllable. His eyes were thin black slits just like a snake, poised, ready to attack. ‘You were s’posed to be on lookout, but the minute you see trouble you ghosted yourself away, innit?’

‘No way,’ said Pea, a high click of fear in his sing-song voice now. ‘I did jus’ what you tell me, Shiv-man.’

‘Yeah?’ Shiv’s eyes widened just a fraction, the two black slits dark ovals for a moment. ‘So why you do a runner when you seed the police comin’, instead of soundin’ the warnin’?’

Pea’s face was flushed and there were little beads of sweat on his pinched cheeks. ‘I never see dem comin’, Shiv,’ he squealed. ‘They snuck up on me. I dittn’t have no time to warn you!’ His eyes were sparkling like Christmas lights and it was impossible to tell if he was lying or not.

‘Not much of a lookout who don’t see nuttin’, eh?’ Shiv snarled, taking another step forward, a swaying movement in his long black coat.

Behind him the rest of the Starfish Gang were lounging up against the swings, watching. Shiv’s right-hand man, Tad, was standing on the kiddie swing, rocking gently. ‘You need glasses?’ he called out to Little Pea. ‘Or mebbe you was too busy savin’ you own self to bother lookin’ out for nobody else?’

Pea stuttered out a few squeaky vowels, like a car engine that wouldn’t start, then spluttered into silence. Shiv was up so close to him now they were almost touching. The sound of the approaching train wailed louder on the tracks, an insistent whine cutting through the searing heat of the day.

Shiv glanced around quickly. Looking for something? Checking the coast was clear? And, as his eyes swung over the roundabout, he clocked me sitting there and his eyes narrowed. Quick as a flash, I pretended I was texting on my ‘phone’. Shiv stared at me for a moment before scanning over towards the gate.

I let out a sigh of relief and I probably should have just stopped filming then and disappeared, but I didn’t. I guess I knew I wasn’t really invisible, but I think I still thought I was safe. My mum was always going on about parallel universes. She said London was full of them, all existing side by side, but never really noticing each other. The Starfish Gang and Shiv and Little Pea belonged to one universe and I belonged to another and I thought that meant they couldn’t touch me.

Shiv’s snake eyes swung back to Little Pea.

‘I stayed right where you told me, Shiv, I swear!’ Little Pea yabbered on. His big fake Nikes jigged up and down on the ground as he spoke. He couldn’t seem to keep still. ‘Mebbe my eyes is goin’ cack. Mebbe I needs to take myself down the op-ti-cian, but I promise I don’t see nuttin’. I dittn’t see da feds comin’.’

‘You see who give my cousin Pats a beatin’ then?’ Shiv hissed.

‘No, Shiv. He was fine when I see him.’

‘Cos someone hurt him bad,’ said Shiv, eyes boring into Pea like he was the one who’d done it. ‘Someone put him in hospital and they gonna pay for it, unnerstand?’

‘Yeah, I unnerstand,’ Pea said, head nodding frantically like those toy dogs you sometimes see in car windows.

‘So, if you saw who done it, you bes’ tell me, right?’ Shiv glowered at Pea and, out of the blue, I remembered another thing I’d heard about him: that he’d smacked his own mum once, so hard he broke her jaw. I didn’t know for definite if that was true – there were as many rumours about Shiv as there were about Pea – but looking at him then it was easy to believe.

Suddenly Shiv’s hand was in his pocket and then in one swift movement it was up close to Little Pea’s face. Little Pea squirmed and wriggled like a fish in a net and for a second I couldn’t make out what was going on. And then I saw the narrow blade in Shiv’s hand, pressed up against Pea’s cheek, gleaming against the scars that ran over it.

If you watch the film, you can hear me gasp when that happens. Shiv might be named after the knife people say he cut the scars on his own face with, but I was still shocked when he pulled it out. And that was when we had the proper ‘movie magic’ moment. The little blade caught the light and sent a disc of fire flashing into my camera lens, obscuring everything in a haze of white. Then, as the viewfinder cleared, I caught sight of the New Kid.

I’d never seen him before, but I knew right away he wasn’t from Coronation Road. Not because he looked different exactly. It was just the way he kept walking, like he hadn’t noticed anything was up. Like he didn’t have a clue who the Starfish Gang were. He was walking right into the middle of a war zone and didn’t seem to realise it.

There was a perfect backdrop to the scene. The grass behind him was yellow and sparse, and beyond that there was a view over the whole of Coronation Road, over the terraces and shops and the miles of tower blocks towards the city in the distance. You could even see the giant wheel of the London Eye nestled between the skyscrapers and the white clouds. And the New Kid had the sun shining on him as he walked towards us, just like the hero in a cowboy movie.

Shiv hadn’t spotted him yet and neither had the rest of the Starfish boys, but Little Pea had, and his eyes widened in surprise. The New Kid was only about ten metres away, but he had on a massive pair of headphones and seemed lost in his own world. He had a face like chocolate sunshine, I thought. I wanted to call out to stop him, but something made me hesitate.

‘You gonna ansa me or what?’ Shiv hissed. The blade was tight against Little Pea’s neck. ‘You gonna tell me who put my cousin Pats in hospital or am I gonna do da same for you?’

‘Um . . .’ said Pea, looking desperately around him like somebody might be able to give him the right answer. Like he could phone a friend or click his heels together and go up in a puff of smoke. He glanced at me and at a couple of little kids who were playing over in the mucky sandpit.

The sun was shining directly on Pea so the mass of tiny scars on his cheeks, similar to Shiv’s, stood out clearly like chickenpox craters only more symmetrical. Even his scalp, beneath his closely shaved head, was criss-crossed with pale scar lines, like someone had drawn them on with something sharp, or splattered hot wax all over him.

The train was close by, its screech staining the air with noise. And I knew deep in my stomach that it wasn’t right to be filming this. That standing by and letting it happen was wrong. But that was when I realised that the New Kid had stopped and was staring. Shiv and the Starfish boys still hadn’t clocked him, but he’d seen them and he had this look on his face – not scared, but sort of angry, and also something else I couldn’t make out.

Little Pea started to giggle, a hiccupy, high-pitched giggle, as the train came hurtling along the track. And suddenly Shiv grabbed him and pushed him up against the railings so his massive feet were dangling just above the ground and he was choking, spluttering, coughing. He cried out and I saw a thin trickle of red run down his neck and drop on to his trainers.

Then the New Kid was right behind Shiv, pulling him off Pea. The train was still going past, roaring behind their heads. And I definitely should have stopped filming then. If I had then maybe things wouldn’t have gone like they did. But I kept the camera rolling as the New Kid grabbed Shiv by the collar and pushed him up against the railings while Pea fell to the ground and slithered out of the way, like a small animal. I was frightened suddenly; my heart was racing so hard I swear you can hear it on the film.

The New Kid looked younger than Shiv – my sort of age, fourteen, fifteen maybe – and smaller too, with cocoa-brown skin, eyes like pebbles and an open face that could not have been more different to the sly, bolting, mad look on Shiv’s. Shiv was panting fast; the New Kid had taken him by surprise. And he might have been smaller than Shiv, but he was strong, because Shiv couldn’t seem to push him off. But the weirdest thing was that he didn’t look frightened at all; he just looked gutted, totally gutted, and I remember thinking: heroes aren’t supposed to look like that, are they? Not when they’re riding in to save the day.

There was a pause – 4.6 seconds it lasts on the film loop. Shiv stopped struggling and just glared down at the New Kid who stared right back at him, and neither of them said a word. No one else dared say anything either. Tad and the rest of the Starfish Gang were a few metres behind the New Kid, standing in a line, fists balled, unmoving. Pea was still sprawled out on the ground, watching. Nobody moved a muscle. I guess nobody had ever seen anyone get the better of Shiv before and we were all waiting to see what would happen next.

After 4.7 seconds, the New Kid let go so fast that Shiv’s knees buckled. Then the New Kid shrugged his shoulders and started walking away. I think he said something, but you can’t make it out on the film because there was a siren wailing in the background. Shiv caught it though. His face flashed with a spasm of anger and for a second it looked as if he was going to lunge at the New Kid. He didn’t. He just pulled himself upright and stared, like he could stab him with his eyes.

‘Come on.’ The New Kid was offering a hand to Pea, who was still sprawled on the floor among the broken glass and the empty crisp packets and old tin cans.

But Little Pea looked up at him and gave him this weird grin. He glanced at Shiv then back at the New Kid’s outstretched hand. Then he shook his head and giggled in his strange, tinny way. ‘No way, crazy boy!’

The New Kid sighed, like he hadn’t expected Pea to take his hand anyway. ‘Suit yourself,’ he said with a shrug.

Shiv started to laugh. His pale eyes were glinting and his laughter was hard and angry. ‘Hey, come on, Little Pea,’ he crooned. ‘Come to mamma!’

In the movies the little guy never goes running back to the villain. Not after the hero has rescued him from mortal peril. But Little Pea seemed to have forgotten that Shiv had been about to stick him with a knife two minutes before. He just jumped up and trotted over obediently. Shiv stood up and brushed down his long leather coat, staring the whole time at the New Kid, who stared right back.

The rest of the Starfish Gang were still lined up a few metres away. Tad looked like a dog straining on a leash, waiting for a nod from Shiv to tell him to rip the New Kid’s throat out.

And Pea? He was jiggling on the spot like he needed a wee, and that was when he glanced in my direction and noticed my camera. I quickly pretended to send a text again, but not before I saw his beady eyes widen, just a fraction. Then he looked me right in the eye and grinned. And I could tell he knew.

The New Kid was pulling his earphones back on to his head and walking backwards in the direction of the park gates, his eyes all the time on Shiv.

From over by the swings Tad grunted, ‘You gonna jus’ let him walk away, Shiv? You gonna let him disrespec’ you like that and walk outta here with his head still on his shoulders?’ He was pumped up, ready for a fight, although his luminous white skin and pale eyelashes made him look a bit like a ghost.

But Shiv just stood there, watching the New Kid until he reached the gate. Then he called after him. ‘Bes’ watch your back from now on, boy!’

When you watch that bit of film you can tell – just like everyone in the park could tell – that the New Kid was dead meat. A marked man. Kaboom.

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.