Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Cold Blood"

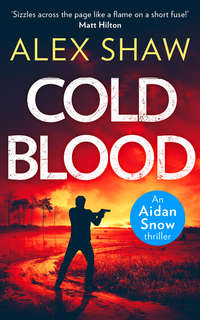

Cold Blood

ALEX SHAW

HQ

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This edition first published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Alex Shaw 2018

Alex Shaw asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

E-book Edition © September 2018 ISBN: 978000830632

Version: 2018-06-20

Hetman – the title of the highest military commander, after the monarch, in fifteenth- to eighteenth-century Poland, Ukraine and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Epilogue

Keep Reading…

About the Author

About the Publisher

Prologue

20th September 1996. SchreinerBank, Poznan, Poland

He set his watch, pulled down the black balaclava and stepped out of the van. As one, the men stormed the bank. ‘Na Podloge Natychmiast!’ On the floor now – the Polish was precise, clipped and accented. With a swift bark from a Kalashnikov, the sole SchreinerBank guard was neutralised.

Shocked customers screamed and threw themselves down as two men in black coveralls pointed their automatic weapons; the dead guard was evidence they weren’t afraid to use them. Two other assaulters wearing empty backpacks vaulted over the counter and headed towards the safe. A fifth and sixth sat across the street in two high-powered BMW saloons. Parked facing down cobbled side streets, the cars were poised for a speedy exfiltration. At either end of the main street identical Opel vans stood, packed with Russian-made plastic explosives. No further words were exchanged as each member of the assault team took up their prearranged positions.

Bull had watched and waited for months for this shipment to arrive, had persuaded an ‘eager’ government employee to give him the building’s schematics, and was now ready to collect his four million Deutsche Marks. A stunned silence took hold of the banking hall, broken only by the whimpering of a youth. Bull looked down at him in disgust. Seven years ago, such a boy would have been his to command in Afghanistan.

Police Training Area, Poznan, Poland

Aidan Snow sat on the wooden bench and stirred his tea. If it hadn’t been for the sound of gunfire and smell of cordite, the training camp would have been idyllic. As part of a four-man training team, Snow had been in Poland for over two months advising the Polish Police Pododdziay Antyterrorystyczne (counterterrorist unit). Now the Cold War was well and truly over, his unit, the 22nd Special Air Service Regiment (SAS), was in demand as the governments of newly independent states attempted to stem the tide of international organised crime and terrorism. He closed his eyes; the last rays of the summer sun seemed reluctant to leave Poznan.

At twenty-four, Aidan Snow had been deployed to numerous hostile locations – some overt, such as Northern Ireland, and others strictly covert; some domestic, some international. His time with ‘the regiment’ had been eventful all right – not the life his parents would have wished for the son of a teacher and a diplomat.

He looked on as the rest of his team showed the Polish trainees the correct way to track and hit a moving target. A target had been attached to a pulley, which was strung between several trees. Some bright spark had pasted a photograph of Andreas Möller to it in a direct reference to the English soccer team’s defeat at Euro ‘96. That summer, famously, Möller had scored the sixth-round penalty that had stopped England getting to the final. The trainees thought this was very funny. The SAS did not.

The team had made some real progress; for a police SWAT unit they were good – ready, in fact, should a real incident arise. Training was still needed, however, to turn this SWAT unit into a truly elite CT team. Their next exercise, which Snow would lead, would utilise ‘The Killing House’ and hone Close Quarter Battle (CQB) techniques.

The regiment’s killing house in the UK was a two-storey building. It was designed and furnished to look like an average two-up two-down, but had special rubber-coated walls to absorb bullets, extractor fans to clear out cordite, and video cameras in corners to record and play back the action in the rooms. Each room had at least one metal target and live rounds were used. The SAS team had built a less elaborate, mini version at the camp to train the Polish operatives in how to enter a room, assess the situation and neutralise any threats. Inspector Zatwarnitski, head of the Polish CT unit, had said a permanent killing house would be built to UK standards. It hadn’t happened yet.

Snow sipped his tea. It wasn’t a bad gig. The Poles were quick learners, as most of them, unlike their British Police counterparts, had already served time in the Polish army before joining up. This gave them an understanding, if somewhat rudimentary, of military procedure and firearms handling. Several of the men spoke passable English, which was good, as none of the SAS team spoke Polish! In cases of misunderstanding, Snow resorted to his Russian, which most of the Poles spoke as their first ‘foreign’ language.

‘My men impress you, Snow?’

‘They are very promising, Inspector.’

‘Good.’ Zatwarnitski sat. ‘History is a funny thing. A few years ago, your being here would have been unthinkable; the West was the enemy. Our hope, our future, our security lay with our Soviet protectors. And then? Like dominos, it all fell. To be candid, we never really wanted to be on the Soviet side. That is why we need you here, Snow; we are tired of the old methods and, of course, want to learn from the best.’

Snow smiled politely. He had been present when Zatwarnitski made the same speech on his visit to Hereford, courtesy of HM Government. The Pole meant every word and fancied himself as a bit of a public speaker.

‘Our biggest fear now is our old protector – Mother Russia. She is wounded and a wounded bear is the most dangerous kind. We really do appreciate your team, Snow.’ The older man reached out to shake the SAS trooper by the hand.

‘Thank you, Inspector, but we’re just doing our jobs. It’s your men that need to be thanked for working so hard.’

‘Modesty is something I hope you also teach.’ Zatwarnitski raised his mug in mock salute.

A shout came from the communications room; both men stood. Moments before, the radio had fallen from the operator’s hand. The call was from central despatch. Armed men had entered SchreinerBank on Wroclawska Street. They were the nearest specialist unit, could they assist?

Zatwarnitski looked Snow in the eye. ‘Are my men ready?’

‘Yes.’

Minutes later, on Zatwarnitski’s orders, the Poles and their SAS training team were in a convoy being led by a very nervous recruit. After eight weeks on the job, this recruit’s first real ‘action’ was as the lead driver on what the SAS referred to as an ‘immediate’. The young officer concentrated on threading his way through the traffic in his new police Omega. Never mind that his siren was blazing; the drivers of Poznan were none too happy to yield. In the passenger seat sat Zatwarnitski, with Snow, who trusted only his own driving, sitting behind.

Wroclawska Street, Poznan

Bull checked his watch. The local militia would be there in five more minutes. A dull thud came from the back room – his men had blown open the safe. Another sound registered in the distance. Sirens? They were early! The men from the safe detail lumbered into view, weighted down, their Bergen packs now full. Giving the signal, he and his 2IC, Oleg, tossed smoke grenades into the centre of the room and out onto the street. It was now time to leave. He felt for the remote detonator, then the two men took up sentry positions on either side of the road to cover the bagmen as they sprinted across, partly concealed by the billowing white smoke. The heavily laden Bergen packs were hauled into the waiting cars.

The recruit slued around the tight bend and into Wroclawska Street, where he saw smoke pouring from the bank, and men… men in black with guns. Forgetting his training, the young Pole panicked and gunned the accelerator, sirens still blazing.

Bull looked up. ‘Blat!’ This wasn’t meant to happen; they weren’t meant to be here so soon. He realised these weren’t normal police vehicles. The lead car hadn’t yet reached the van, but it would at any second. Dropping to one knee, he pressed the button on the remote detonator as his men opened fire.

The second car came into view. The explosion tore through the Opel van, hurling debris across both lanes of the road. The full force of the blast caught the second Omega, tossing it up and sideways like a child’s plaything. It smashed into the façade of the post office. The lead car punched through the smoke, the recruit screaming as he lost control of his car. The force of the blast sent his charge headlong into the entrance of the bank. He and Zatwarnitski were killed instantly. At the end of the block the other van erupted, levelling a newspaper kiosk and gutting a bakery. The first BMW roared off and away.

As the remainder of his men delivered suppressing fire, Bull noticed movement in the first Omega. He moved to the devastated vehicle. The front of the car had been turned into a mass of twisted steel and broken glass but… a passenger in the back was alive!

The man was dressed in his own black coveralls. Bull looked down at the young, ashen face with dark-brown eyes. Who are you? he thought.

The mouth moved and, through the pain, a raspy voice whispered, ‘Piss off!’

Had he spoken in English? Who were these police who had arrived so quickly? The man tried to move but was pinned to the seat; blood seeped from his mouth and ears. This hero would die soon regardless. Bull pulled up his balaclava and smiled, letting the boy look at the last face he would see on this earth. Shots zipped past his head. More black-clad figures were running through the smouldering debris, returning fire.

‘Blat!’ He cursed again and ran back to his car. Tyres screeching, they disappeared into the suburbs. Tauras ‘Bull’ Pashinski fell back against the leather seat and closed his eyes. He was now a rich man.

Chapter 1

July 2006. Pushkinskaya Street, Kyiv, Ukraine.

He was woken by the early morning sun warming his face and the excited barks of his neighbour’s dog scampering around on the communal landing, waiting for his master to lock the door and join him. Outside, three floors below, the swish of the street sweepers tidying up the pavements with their birch-twig brooms echoed gently. Aidan Snow opened his eyes and tried to focus on the ceiling. Gradually the image sharpened as his eyes became accustomed to the bright sunlight. He rolled onto his side and his nose found the empty glass bottle of Desna Cognac nestling between his pillow and the arm of the bed settee. Snow was wide awake now and knew that, whatever he tried, he wouldn’t be able to sleep. He was a morning person, which wasn’t exactly a blessing after nights out. Swinging his legs out, he sat up. Never again, he told himself, and not for the first time. The parquet floor was sticky from spilt beer. Snow walked to the balcony doors and opened them, breathing in the fresh morning air. The street-cleaner van approached from the far end of Pushkinskaya Street with hoses spraying water over the dusty road and pavement. Kyiv glowed with pride in the morning sun, the workers below intent on making her even prouder. A well-oiled Soviet machine that still worked fifteen years after the Union had ceased to.

Snow leaned against the balcony railings and gazed at the Ukrainian capital city he now called home; he had yet to tire of the view. To the left, his street, Pushkinskaya, crossed Prorizna Street and carried on downhill through a high, ornate, double arch into Independence Square. To the right it also sloped downhill, crossing both Bogdan Khmelnitsky Street and Boulevard Taras Shevchenko, before ending at Shevchenko Park and University. These were named after the great Ukrainian writer, their equivalent of Shakespeare, and not the Chelsea footballer, as his pal Michael had insisted. Carefree locals drinking beer and enjoying life were to be found at these meeting places at either end of Pushkinskaya, not to mention the bars that dotted its entire length. For the first time since Poland, Snow was at peace, or as near to it as possible. He took another deep breath – at peace, that was, except for the hangover he was battling.

It had been another night of cheap beer and ex-pat posturing at his favourite bar, Eric’s Bierstube. There had been the usual faces: the TEFL teachers sitting in one corner, trying it on with their most promising or largest-breasted students, and the so-called ‘serious businessmen’ in the other, downing shots as toasts to clinch deals. The rest of the clientele had been made up of either ‘new Ukrainians’, trying to look casual in their Boss suits, or local university students sipping slowly.

Snow had sat in his usual corner, his back against the exposed brickwork, and looked on with Mitch Turney and Michael Jones, who played their game of ‘guess the bra size’. As always, the Obolon beer had flowed freely. Michael had guessed at least one correct size before being called home by his wife, Ina. Mitch and Snow had then adjourned to the flat, where one last drink had taken three hours and resulted in five empty beer bottles and the end of the Desna. Mitch had fallen into a taxi and Snow had fallen on the floor.

He took one more deep breath and walked to the kitchen, collecting the empty bottles en route. His head swam. Never again. It was at times like this that being single was both a blessing and a curse. He had no one to tell him not to drink like a fool until all hours, but no one to come back to. So he drank and partied like, as Mitch put it, ‘a college student on midterm break in Tijuana’.

Snow padded around his functional kitchen and removed a carton of yogurt from the fridge, which contained the bachelor’s bare minimum: a block of cheese, milk, yogurt and a hunk of ham. The space usually taken up by beer had been liberated. He sipped the thick local strawberry yogurt straight from the milk-style carton and opened the kitchen window. July, and Kyiv showed no signs of cooling down.

He scratched the mosquito bite on his left buttock. The heat he liked, the heat he enjoyed, but the damn mozzies could be a pain in the arse! They seemed to hide during the day, only to break in and assault him at night if he forgot to plug in the repellent gizmo.

‘You’ve grown soft,’ he told himself. ‘How did you ever pass selection; a man who complains about a few bites?’ The former SAS soldier smiled to himself. ‘Perhaps I have, but it bloody itches.’ Snow pulled open a draw and took out a packet of pills. He popped two and chased them with yogurt. Never on an empty stomach, his mum said.

Saturday morning and in a couple of hours the streets of the capital would be teeming with people. The Kyivites shopping or promenading along the city’s main boulevard – Khreshatik Street – and the visitors from other regions come to sightsee. Kyiv – he loved her. She was graceful, cultured and beautiful, yet overlooked by the West. He hadn’t abandoned her for the holidays like his fellow teachers, but stayed to savour the hot Ukrainian summer.

This would be the start of his third year teaching at Podilsky School International and he felt at home. Kyiv had been the third-largest city of the mighty Soviet Union, but here in the centre, for all its grand buildings, it still retained a village-like atmosphere, with its inhabitants living just off the main shopping streets. Snow hated towns but Kyiv was different, with its vast number of trees – more than any other city in Europe (a local had told him) – several large parks and a river (again, according to the same source, the widest in Europe) running through the middle. It was both town and country in one. Snow was the only foreigner in his building and Kyiv wasn’t yet spoilt by tourism. It was rare to hear a foreign voice on the street, and those he did hear he usually recognised, by sight at least, as belonging to ex-pats or diplomats.

Just over one more month and school would start again. These drinking binges would have to stop, or at least be confined to the weekends. But not yet. He finished his yogurt and dressed in his running gear. Saturday or not, he wouldn’t allow himself to miss a run. It was a rule he had learnt in the SAS and one he wouldn’t forsake now he was a civilian.

Snow took the steps down to the ground floor to warm up his leg muscles before starting his ritual of stretches in the street outside. It was just after 8 a.m. – later than he normally ran, but, as it was a Saturday, there were fewer people up. Running was something that had become second nature to him; it helped clear his mind. He ran most mornings, although this was tough in the Ukrainian winter, with an average temperature of -10°C. It wasn’t the cold that made it difficult, but the ice. Walking up and down the city’s hills was treacherous and running became suicidal. Thus far, Snow had found the solution by running around one of the city’s central stadiums, either ‘Dynamo’, home to the famed football team, or ‘Respublikanski’, built and used for the 1980 Moscow Olympics. The fact that both of these were open to the general public was another Soviet legacy he embraced.

Satisfied he’d stretched enough, he moved off at a steady pace. He ran down Pushkinskaya until he hit Maidan. Dodging the stallholders setting up their kiosks, he pumped his legs up the steep Kostyolna Street. Cresting the hill he entered Volodymyrska Hirka Park. The morning air hadn’t yet become dusty and a breeze blew in from the Dnipro River below. He was taking his weekend route, as he had nowhere to be in a hurry. Reaching the railings overlooking the river, he turned left, following the footpath. The park followed the river until it abruptly ended at the mammoth Ministry of Internal Affairs headquarters. As Snow ran past the building and towards the British Embassy in the adjoining street, he was once again taken by the sheer size of the place. Looking much like the Arc de Triomphe, but larger, he estimated, the Ukrainian government building wasn’t on any international tourist ‘must see’ lists, but he made a point of staring none the less. It was one of the many things that made him want to stay in Kyiv.

Snow had grown up with a love for the unusual. His father had been cultural attaché for the British Embassy, Moscow, in the mid to late Eighties. As such, Snow had been at the embassy school there for much of his formative adolescent years. The upshot of this was that Snow’s Moscow-accented Russian was all but flawless. Ignoring his parents’ protestations that he go to university, he had joined the army immediately after his A-levels. Turning down a chance at officer training, he’d completed the minimum three-year service requirement before successfully passing ‘Selection’ for the SAS. He’d wanted to be a ‘badged member’ ever since seeing the very public ‘Princes Gate’ hostage rescue (Operation Nimrod) at the Iranian Embassy as a nine-year-old in 1980. His parents had laughed it off and bought him a black balaclava and toy gun, but, as the years passed, Snow’s desire to join only increased. Then he was in. His boyhood dream fulfilled and, although begrudgingly, he knew his parents had been a bit proud. Then it all went wrong.

Snow slowed to a walk as he entered Andrivskyi Uzviz. The steep cobbled street, lined with souvenir stalls, art galleries and bars, was quite capable of inflicting a broken ankle on the unwary. He descended the hill. His right thigh had started to throb. The sensation always brought back memories of the accident in Poland, the unbearable pain he had felt, pinned to the backseat of the car, unable to move, unable to reach for a weapon to defend himself. The sound of flames and the vicious scent of petrol filling his lungs. Then that face, the serpentine eyes that had looked into his and pronounced sentence upon him.

Snow shivered in spite of the warm morning air. After the accident the doctors had said he would always walk with a limp; that the bone would be weakened and that the muscles might not knit back together. They advised that he be taken off active duty, given a desk or other duties. He ignored them and attempted to defy all medical opinion by pushing himself harder than he’d ever thought possible. He spent hours in rehabilitation, first with PT instructors and then, later, on his own. He was twenty-four years old and a member of the 22nd Special Air Service Regiment; no one was going to tell him what he could or couldn’t do.

His effort paid off and the regiment doctor had signed him off as fit for active duty. No limp, just a scar. However, the one thing Snow hadn’t admitted to anyone, least of all himself, was the toll taken by the mental scar. The nightmares, for want of a more macho term, that prevented him from sleeping and turned him from jovial troop member into withdrawn loner. Snow had sought professional help and then accepted the truth. He left the regiment within the year with an honourable discharge, his military career cut short.

He felt his leg ease as he reached the bottom of the hill and swore at himself for yet again allowing the past, something he couldn’t change, to ruin a perfectly good day. The sun was now higher in the sky as he jogged through central Podil and headed towards Hydropark, the largest island and park in the Kyiv stretch of the Dnipro River. Perhaps he’d risk a swim?

Tiraspol, capital city of Transdniester, disputed autonomous region of Moldova

The two men embraced like the old comrades they indeed were. Bull regarded the face of his friend and former Spetsnaz brother Ivan Lesukov. ‘You have grown fat, old man.’

‘And you ugly.’ Lesukov laughed heartily. ‘I see that Sergeant Zukauskas has not changed – you still look like a pig!’

‘That is why the Muslims hated me so much!’ Oleg, the barrel-chested Lithuanian winked.

Lesukov raised his glass and the others followed. ‘To fallen comrades.’ The vodka was cold, having been stored in the fridge Lesukov kept in his office.

‘You have an empire here, Ivan,’ Bull said, congratulating his friend.

‘I am the King of Chairs,’ Lesukov replied, spreading his palms at the window, which looked out over the factory floor below. ‘The main industries of our country are furniture and electronics, but we can’t sell abroad because of those bastards in Chisinau.’ He shrugged. ‘Our products do not carry the Moldovan government stamp and, as our country of Transdniester is not recognised outside of its own borders, we cannot sell.’ Lesukov refilled the glasses. ‘But I don’t care a shit about the electronics or even my chairs. What I have brought you here for today is to discuss how you can help an old comrade with his export business.’ He raised his glass. ‘To success.’ Again, the glasses were drained.

Bull spoke first. ‘I understand that, of late, you have been having some logistical problems?’

‘Our “friends”, the Russians, are understanding, if not supportive, of our “specific” situation. They let my goods pass freely through the security zone. In fact, some of my goods even originate from the weapons they are “peacekeeping over”.’ He tapped his nose with the end of his index finger. ‘So, with the Russians, here in Transdniester, I have no problem. They are good boys. It is the Moldavians to the west and the Ukrainians to the east that I am having problems with.’ He balled his fist.

Tensions between Transdniester and her neighbours, Moldova and Ukraine, had been high since Transdniester separatists, with Russian support, broke away from Moldova in 1992, declaring independence. The short civil war that ensued had left more than 1,500 dead. An uneasy truce, brought about by Russian ‘peacekeepers’, had stabilised the region since then. In a strange turn of events, Europe’s biggest Soviet Army weapons cache was now to be found not in ‘Mother Russia’, but near the Transdniestern town of Kolbasna, guarded by the two thousand Russian soldiers acting as ‘peacekeepers’.

A ‘confidential’ 1998 agreement between Russia’s then prime minister, Viktor Chernomyrdin, and Igor Smirnov, the self-appointed president of Transdniester, to share profits from the sale of 40,000 tons of ‘unnecessary’ arms and ammunition had made Lesukov and men like him very wealthy. However, once a copy of this agreement had come into the hands of the Associated Press, there had been protests in Washington and a scandal in the European media. Russia had denied the story as preposterous and Ukraine had condemned any potential arms dealing, stepping up the size of their border guards units.

Lesukov was beginning to feel the pinch as he found it harder and harder to get his goods out of the country.

Lesukov paused and refilled the glasses. ‘How many of the Orly still serve with you?’ It was a question to Bull. Orly, the Russian for ‘eagles’, wasn’t a regimental title but a traditional name used to signify fearless fighting men.

‘Of my Brigada, six; however, since becoming freelance we have many more good men.’

After leaving the Red Army Spetsnaz, Bull had recruited other former ‘Special Forces’ soldiers from numerous Soviet Republics. These were some of the most highly trained soldiers in the world, yet had been discarded when the Union crumbled. He had bought their loyalty for little more than a few hundred dollars each; as a hero of Afghanistan he already had their respect. For the past fifteen years he had built a reputation in several war zones as a ruthless leader, mercenary and surprisingly good business facilitator. He had brokered arms deals with the Mujahedeen, rebels in Georgia’s breakaway Abkhazia region, and insurgents in Africa, to name but a few. Now it was only natural that one of the main suppliers of weapons should want his direct assistance.

‘What had you in mind, my old friend?’ Bull asked.

Lesukov smiled, raised his glass again. ‘To women.’ The other two followed. It wasn’t that they especially wanted to honour women, just a Soviet tradition for every third toast. He placed his hands flat on the metal desk.

‘The Ukrainians have their own group of Orly, called the “SOCOL”. They are a highly effective anti-smuggling and anti-organised-crime unit. This I could normally admire; however, they have now turned their focus on my shipments. In the last two months alone they have intercepted three of them…’ His voice trailed off as he totted up on his large fingers how much he had lost, then doubled it. ‘They have cost me almost three million American dollars in profit!’ His face had grown red and any hint of levity had passed.

He sighed and remembered the dusty mountains of Afghanistan some eighteen years before, and the young Spetsnaz captain who had fought next to him. ‘You were the best in Kabul, saved us all. Now I ask you to save me again. I want you to stop this SOCOL team once and for all.’

Oleg, who had listened quietly, let his tongue run along the outside of his top lip. He loved action and had grown weary of ‘business’. To take on a real target was what he lived for. He looked at his CO.

Bull folded his arms and nodded. ‘It can be done, but of course there is a price.’

Lesukov’s eyes glinted; he had anticipated this. ‘I will give you ten per cent of each shipment that passes successfully into Ukraine.’