Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

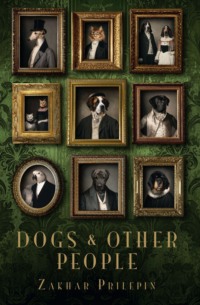

Buch lesen: "Dogs and other people"

Zakhar Prilepin. Dogs and other people

© ООО "Лира", 2025

In memory of Sasha “Angry” Shubin, the angel of our family

St. Bernard's Days

Shaking off the snow and stomping my feet, I opened the door to my city apartment – and there I saw him.

He had been living with us for three days now.

I had been busy travelling, and my family had said nothing about our new resident – a St. Bernard puppy, who still had no name: it hadn't come yet.

The puppy lay in the middle of the square hall, with high ceilings.

He already counted all the people who lived in the apartment and made himself at home, and there I was – large, smelling of cold, with 40 roads on my coat.

Slipping and with his paws going in different directions, he quickly ran into the corner, where with his back to the wall, he stared at me: “Who are you?”

“What's this shmel1?” I asked, unable to resist smiling.

He was fluffy and a bit clumsy like a shmel: ginger, summery, harmless.

I took an instant liking to him.

“Shmel!” The children shouted “Shmel!”

And that's how he got his name.

* * *

We soon took a fateful decision: we went to live in the country, where we had a two-story, rickety and creaky house on a shaky foundation – but with a real stove.

Shmel, I remember, lay on top of enormous sacks and bags in the trunk of our large offroad vehicle, looking with bemusement at the backs of the children's heads and waiting for them to turn around to look at him: I saw the pleading expression of his eyes in the rear-view mirror. He occasionally made a decisive attempt to climb over to the people on the backseat, but the children cheerfully pushed him back to his place.

When we reached the house, we spent a long time unpacking, filling the old cupboards with new life, and Shmel wandered around, loudly stomping on the floor and taking a delight in the abundance of old, kind, pungent smells.

On the morning after our arrival, after putting the kids in the car, the snow sweeping in our wake and a myriad of voices ringing every time we drove over pits and bumps, we went into a gaping forest, like a table laid out for the most long-awaited guest.

We opened the trunk and carried him out, impatient and stunned with happiness. Even as a puppy he was a heavy chap.

The sky rained down its triumphant bounty on him.

I carefully put him on the snow – and he furiously ran off, his chest thrusting into the snow drifts. He jumped and sank down up to his nose. This surprised him – but he gathered his strength and made a new leap forward.

This is what happiness looks like: little Shmel in the forest clearing accompanied by children's laughter trying to overcome the resistance of the dazzling world of snow.

* * *

An old beekeeper lived across the way from us.

Once, about 40 years ago, when he was a man old before his time in his sixth decade, a widower, with an adopted daughter and two grandchildren, he fell deathly ill – and decided to die in the quiet of the forest, far from the city.

He was very weak – and his daughter, a young woman, left her two sons with her husband and quit her job to look after him.

Everyone thought he'd last a month or two at most – the generous doctors wouldn't give him any more time – and then his daughter would go back to her kids and get her job back.

But the old man kept hanging on.

He hung on for three months, then a whole year – although he still seemed weak, breathing his last breaths.

Every time when his daughter was eager to leave, the old man said goodbye to her forever and lay down on the stove, asking her to heat it up properly: “I'll depart in my sleep – at least so I don't freeze immediately.”

“Well, next spring,” his daughter decided, staying a second spring, a second summer, a second autumn, and then one more winter.

And in the third spring she planted a vegetable garden under her father's supervision.

Now the old man only ate cabbage and beetroot.

Then the elder son of his adopted daughter finished school, and the daughter thought she might stay for good. Accustomed to living with the old man in the middle of the dense forest, she decided that now there was no need to hurry – her younger son would also soon finish school.

The next year the old man found a new lease of life and decide to keep bees.

Since then countless years have passed.

Sometimes the bee-keeper, leaning on a sturdy dry stick almost as ancient as himself, walked around the village. Without looking at anyone, the old man would suddenly shout a word or a phrase, as if they had been excerpted from a long speech unknown to us.

Perhaps he was talking with his past.

That winter, when Shmel came to the village, his adopted daughter died.

The old man kept on living. He was about 95 years old, and for half a century he had not been in any hurry.

From time to time, I would encounter him on the street, but I could never get a proper look at him: you might just as well try to remember the pattern of tree bark.

Blackened, but with tufty white eyebrows, the old man was overflowing with time.

His face was crossed with several black veins resembling the lashes of a whip. His mouth was puckered inwards. His ears, resembling autumn mushrooms, had furry webs inside that turned silver in the sun.

* * *

Besides the beekeeper, our small, remote village surrounded by dense forest was inhabited by the following citizens:

Our closest neighbor was Nikanor Nikiforovich: the buildings in our yard were next to his fence, but we hardly saw him – though we heard each other every day.

He was at least 50, moderately pot-bellied and somewhat bandy-legged, and he kept dogs and went off hunting for days on end. He also liked fishing: he used nets, rods and many other cunning devices, but always fished alone.

Once I saw him hauling two sacks of fish: he was gloomy and in a hurry, like a thief.

Nikanor Nikiforovich seemed to look at you sideways, with a squint, and you got the feeling that he had a gumboil he was trying to hide.

When he talked he used his hands, like a southerner. If there was something he didn't like, he immediately raised his voice, and shouted like he was concussed – as if he couldn't hear himself.

Sometimes I was the unwilling witness when he discussed the neighbors, either with someone I couldn't see behind the fence, or probably with himself. All of the neighbors, in Nikanor Nikiforovich's opinion, were not such wonderful people.

Any fish that the neighbors caught he regarded as being his own, stolen from him. Any new building that the neighbors put up was an eyesore for him.

He couldn't stand young, fertile women, and almost crowed in irritation: “…there she goes, carrying her ass! Here she comes, carrying her ass!” It sounded as though the woman was carrying a basket back and forth, full of apples from his orchard.

Deep down, he was a good guy – if you didn't have anything to do with him.

Most people in the village kept their distance from him.

Nikanor Nikiforovich had a wife. She visited him once a month, or every three months.

Across the road from Nikanor Nikiforovich lived Ekaterina Eliseevna with her two mentally ill daughters – she was an incredibly kind woman who had been allotted this terrible fate for reasons unknown. She was quite mentally sound herself: she was devout and hard-working, bearing wrongs without complaint. Her daughters inherited the illness from her husband – although he was sane, just silent. But his great-grandfather, it seemed, had suffered from mania in the old times, he was treated but was not cured, and flung his ailment down to future generations.

The daughters were plump, and if something interested them they stopped still and stared at it with their bird-like eyes. They didn't like loud noises, in summer they drank tea in the yard, and in winter they once made a snowman, then had a loud quarrel over something unimportant, and tore the snowman to pieces. In the end one of the daughters fell down in the snow and started crying like a little girl, bringing Ekaterina Eliseevna out of the house.

At the edge of the village, lived a 25–year-old drunk Alyoshka with his mother, a bed-ridden invalid who I never saw.

Despite his young age, Alyoshka looked like an old, pathetic alcoholic. His liver could no longer cope with all the moonshine and other gut rot that he poured into himself at every opportunity. From morning to evening, in spring and autumn, Alyoshka's face was horribly puffy.

In the neighboring village there was a store – the only one in the entire forest, which was a hundred kilometers along and across. Every morning, without a ruble in his pocket, Alyosha would set off for his destination and patiently go hat in hand to the people standing in the line, annoying them tremendously. He was beaten from time to time, and he came back with a black eye, or a torn ear, or dragging a coat with one sleeve, having left the other one by the shop to be fought over by dogs.

Three empty houses away from Alyoshka lived a husband and wife known as the Blind ones.

In fact only the man was blind, and his wife could see perfectly well, but the villagers gave them this name because the Blind ones always walked together, and no one had ever encountered them separately.

Ten years ago, the man had begun to lose his sight with catastrophic speed, and they decided to move to the village to avoid suffering from their plight among hordes of people. They bred goats and lived a solid but very quiet life. It seemed that along with the man's sight they had both lost their voices. The wife responded to greetings with a deep nod, and the man stuck out his neck like a goose and turned his head from side to side, as if hoping to detect the scent of the person they had met.

At the village store the wife pointed at the groceries they needed without naming them, and her husband stood next to her, with a very straight posture and as if he were looking over other people's heads. With strong hands he firmly clutched his staff: although his wife guided him by his arm, he always used his staff to tap the space in front of him.

The newest resident of our village was a retired prosecutor – one summer he built himself a two-story brick house and lived a separate life with his wife.

The prosecutor had six dogs, four of them hunting dogs. The hunting dogs were tied up, and sometimes barked for hours. The two other dogs, of some curly breed, like happy sheep, ran around the village. I once asked the all-knowing Alyoshka why the prosecutor did not keep the dogs in the yard. Alyoshka shared his knowledge:

“The prosecutor said that this breed is supposed to run free.”

“The prosecutor should know best,” I agreed. “Who to keep chained up, and who should be free”.

We had a good village, although all the people I've mentioned were not very friendly towards one another.

The other residents visited from time to time, usually in summer and for holidays. But we were always there.

The forest around us was a pine forest, bleak and dark.

Animals lived in the forest. There were far more of them than there were of us.

We were certain that we were living on the edge of a sanctuary. The animals may have thought that we were the inhabitants of the sanctuary.

On dark evenings, a large moose came out on to the other shore of the small forest creek that ran along the edge of our village, and looked at the rare lights flickering in a few windows.

* * *

In a year, Shmel grew to be an enormous beast, and by the age of two he was taller than any other dog of the largest breed that he encountered.

Shmel liked everything living, even cats.

He had no complaints with other dogs, and if necessary he was happy to play the fool with them.

But most of all he was interested in people.

He exuded tenderness, bursting with the desire to meet or renew previous brief friendships. All the village residents without exception were desirable companions for him.

At the very end of December that year, it was as if a bag in the sky had been untied and the snow fell in furry clumps.

On the first January morning I could barely open the door. The porch, the railing, the yard and the roofs of buildings were covered thickly.

Shmel was fast asleep in the yard – we didn't have a kennel for him.

However, he was so hot that the snow on him melted, and only a faint frost lay on his cheeks, and his sides were silvery.

The kids and I stamped out a few paths. Sending my sons to the barn roof, I ordered them to sweep some of the snow off – the roof wouldn't take the load.

But as soon as they had started, the snow began falling with tripled intensity: if you waved your hand in the air, you'd get a large, solid snowball.

“Time to stop,” I ordered.

Shmel kept sleeping.

In a year, Shmel grew to be an enormous beast, and by the age of two he was taller than any other dog of the largest breed that he encountered.

We decided that New Year's Eve must have been too loud for him. The dog was full of impressions and dreaming of stars falling from the merry noise, and barely noticeably wagging his tail.

…The next day I found Shmel in the same place. The dog was happily snoring, but I still gave him a push to make sure he was fine. Shmel immediately started kissing me, and then everyone else.

But he also slept through the third day.

And then the fourth and fifth. And on the sixth he could hardly keep his head up when I took him for a walk.

It still remained for us to discover the mystery of his January slumbers.

* * *

As soon as the door were closed and the lights were out, Shmel climbed up an enormous snowdrift and on to the roof of the barn, and jumped off it into another snowdrift – outside the fence.

The village was luring him and waiting for him, revealing scents, calling him with the sound of dishes and the voices of people.

In a morning trot he advanced through the village, feeling like an angel on a Christmas tree, albeit a shaggy one.

Shmel had learnt to cope with doors and latches since childhood. Whenever he encountered any obstacle he used his routine: he would press down the handle with his paw, put his claws through the opening, and then open the door with his nose. Or, without too much of a run-up, simply walking, he would butt the door with his head. This soft blow, despite Shmel's unhurried pace, had incredible force.

First in his path was Ekaterina Eliseevna's house. Women's laughter could be heard in the windows, and the smell was enough to make Shmel's head spin.

…First she heard the gate opening – “Who's that?” Ekaterina asked in surprise. “Is that Alyoshka?” Then the door opened…

Ekaterina Eliseevna's unfortunate daughters, unable to see in the darkness, jumped up off their chairs and shrieked. Ekaterina Eliseevna was sitting with her back to their door. Used to the noisy silliness of her daughters, she expected to see Alyoshka in a ridiculous outfit, and did not expect any other bad things – what could be worse than her ruined life…

But she saw the enormous snowy head of the beast.

With a powerful tail Shmel knocked one of the girls off her feet – what were everyday items to him that evening, the shovels and brooms, and even the buckets and salad bowls on the benches? All of this noisily came crashing down and was partially smashed.

“…My God,” Ekaterina Eliseevna threw up her gentle hands, finally seeing who the guest was. “It's the neighbors' dog”.

“A dog!” her scared grown-up children echoed. “A dog!”

…After a minute everyone settled down.

The daughters gradually came down from off their chairs, as if immersing themselves in scolding water.

Ekaterina Eliseevna held out a pancake for the dog. The pancake vanished into his grateful mouth.

The daughters, shaking a little, started laughing. Both of them, not taking their eyes of the dog, gave him more festive pancakes.

…How they fed him!

From their hands. From the frying pan. From the pot. From the salad bowl. From the saucepan. From off the floor.

Finally, from the snow in the yard, where he was brought a mixture of stews, salads and pies scraped off the plates.

Shmel ate as a fine man should: furiously, not forgetting to raise his head and give thanks with a tender glance from under his drooping eyelids and with a somewhat hurried half-wave of his tail.

He went to the unhappy girls like a groom who they no longer hoped to see.

And he left them in complete delight. From their hands. Their hair. Their clothes. Their hospitality. He kissed them all at once, and in turn.

Ekaterina Eliseevna had long given up dreaming of a grandson – and now he had come to them.

And just the way that real men return from campaigns and long trips: at night, in the snow, unexpected, tender and very hungry.

Putting her chin on her palm, Ekaterina Eliseevna looked at him in admiration.

In the evening, with the all-round support of Shmel, the blushing girls finally finished making the snowman, without quarrelling this time.

* * *

The retired prosecutor moved to the impenetrable forest because in his old age he wanted to avoid meeting anyone he had seriously offended while carrying out his stern duties.

He had long been accustomed not to make contact with people and not to look for friendship. He greeted the local residents from a distance.

The windows in the prosecutor's house, with the curtains always closed, even resembled arrow holes by their shape. He kept several guns at home.

Until his dogs got out of hand, I was even happy that the prosecutor did not make any particular efforts to coordinate his life with the lives of neighbors.

“…yes,” he seemed to say. “I live the way I do, my dogs may yap in all directions, but they bark in my yard, and your dogs have every reason to bark back.”

After several years I never found out what the prosecutor looked like up close. I also only caught a brief glance of his wife.

No one from the village talked to them. They did not receive guests.

On New Year's Eve, the prosecutor and his wife had a fireworks display for two in their yard. Satisfied, they went to drink champagne, forgetting to close the door, which on all others days and nights was permanently locked.

Least of all were they expecting guests that night.

Their house had a high foundation, as if they were expecting floods. When you entered the house, you had to go up tall steps which led straight to the kitchen. The kitchen was connected with the hall. In the middle of the hall lay a huge and expensive rug.

The prosecutor and his wife sat together at a modest table – two glasses, two red plates, nothing extra – when they felt a draught passing around their legs.

“The door,” said the wife. “The door. It's open.”

She still hoped that it was just the winter wind, but she remembered that it was not windy at all – and she saw the heavy snow falling outside the window, which was not swirling or drifting.

Prepared for this day for so long, the prosecutor sighed and realized that all of his efforts had been in vain. He could not find the least energy in himself to get up and take a gun.

Swift steps could be heard coming up the stairs – evidently there were several people. The guests did not close the door.

None of the neighbors, even if they visited without an invitation on New Year's Eve, would have done this.

On the contrary, the neighbors, as if disguising their embarrassment, would probably have shouted from below: “Hey there! It's us! Just for a minute!”

These visitors planned to make a quick visit – and leave immediately. They knew that if they shut the door they would have to open it again on the way out, wasting time. They were experienced!

The prosecutor stretched his long legs and nodded to his wife.

“Forgive me, my dear, but that's how it is. I couldn't protect you. But we've lived a good life. Even though all these years I hardly paid any attention to you. I hoped to correct previous mistakes by moving to a new house. But…”

The guests were moving silently and confidently. The steps were growing nearer.

The wife gave a beseeching look at her husband.

He quietly put down his fork next to his plate, wishing least of all to look foolish at such a moment.

The kitchen table with the washed dishes fell with a crash in the kitchen.

“What louts they are…” the prosecutor thought with a light nausea.

His vision blurred. He suddenly felt tired, as though he had just done 100 sit ups.

“I mustn't faint,” he said to himself. “There isn't long to go now.”

An enormous head appeared in the doorway.

“What do they need a dog for?” was his first thought. “What sort of show is this?”

But the dog was alone, and he wagged his tail with an enormous sweep.

The wife got up. She smiled, with her hand on her heart.

“he'll… break… the vase,” she said to her husband as if apologizing, nodding at the dog.

…Half an hour later Shmel, as usual, without expecting a trick or a rebuke from the world, was sleeping on the rich carpet, snoring.

The prosecutor and his wife were kissing on the sofa.

* * *

Alyoshka had a fluttering heart, and its beating seemed to be more inappropriate the longer it continued.

He regarded his existence as a misunderstanding.

His heart pained him, and he drowned it like a puppy. But he hadn't completely drowned it – and every morning it climbed out of the deadly water on to dry land. And it started to howl so mournfully that Alyoshka immediately began to search for new water, so that the puppy would finally choke.

His mother fell ill over 10 years ago. Alyoshka was just over 10 at the time.

Alyoshka had never seen his father, he had no education, he knew no love apart from his mother's, and he had no one to be friends with.

As long as Alyoshka could remember, he had always been drunk or hungover, although he hardly had any money to maintain this state – apart from the day his mother's pension arrived, and the pitiful benefit to care for her.

However, just as a prisoner will always deceive the jailer by thinking about escape every day, Alyoshka always found gaps in existence to leave it for good.

…As for Alyoshka's mother… she was waiting for a doctor.

The nearest doctors, living 100 kilometers away from us, decided that our village did not exist, after three ambulances broke down one after another on the way here. For over a year, a board with a red cross had adorned our village road with incredible ruts and amazing potholes. In spring and fall it was covered with huge puddles, the depth of which could only be fathomed by experience. In winter the road was covered with snow, and the snowdrifts along the roadsides reached the windshield of the car.

In summer Alyoshka's mother felt better – and she did not forget about the doctor, because she salted cucumbers and tomatoes, which Alyoshka brought from somewhere, claiming that he had been given them.

But when the weather grew cold Alyoshka's mother once more began to wait for the doctor.

Lying on the bed, from day to day she rehearsed the story about what hurt her, how and when, and then tried to imagine how many wonderful, new and unusual types of medicine she would be prescribed by the young and energetic doctor, some of which he would bring in an enormous aromatic first aid kit.

…Shmel couldn't open the door to Alyoshka's house for the simple reason that it had no handle, or hinges.

When he went out, Alyoshka lifted the door and shifted it to the side a little, and then put it back.

For a while Shmel walked around the house, the poorest in the village.

Several times he brought his nose up to the iced-over glass, in the hope that he would be noticed inside.

Alyoshka was fast asleep at the table.

His mother was sleeping to the crackle of the radio, until the persistent noise from outside woke her up.

“It's a doctor,” she said in a suddenly bright voice.

“It's a night-time New Year shift,” she explained to the sleeping Alyoshka quite seriously.

With the crutch lying next to her bed she prodded her son.

“Sonny, sonny, sonny,” she repeated hurriedly. “The doctor's here.”

Swearing and waving his hands, forgetting where he had fallen asleep, Alyoshka got up and stood there for a while, stretching his arms.

Finally realizing where he should step to turn on the only lamp in the house, he waited for a minute in the weak light, listening to his mother's pitiful whispering.

Finally, he shifted the door – and in the darkness he saw the puppy that he had been drowning for so long, only this puppy had grown and was now enormous.

Shmel prodded Alyoshka with his shaggy head – and Alyoshka dropped to the ground.

In his hurry to get in, Shmel stepped on Alyoshka's stomach, head and other places.

Overcoming this annoying obstacle, Shmel immediately jumped over to Alyoshka's mother on the old bed, knocking over a stool on the way with expired medicine on it.

Taking a place by the wall, he looked fixedly at Alyoshka's mother.

His powerful tail rhythmically slapped the wall.

Suddenly she laughed.

Rubbing the snow off his face, Alyoshka sat down – and suddenly he remembered that the last time his mother had laughed like this was when he was 12 years old. They had been gathering berries.

* * *

The Blind ones, who bred goats, were waiting for a new addition to the family all through the second half of December – goat kids.

Every new kid, especially at New Year, was a source of joy for them. The kids were silky to the touch when they were born. They trusted the world, smelt of warmth and happily wagged their tails, sucking on their mother's udder.

On the night before New Year's Eve, the wife ran out several times to see how things were going., The mother goat was anxious, and looked at her with a direct, shaming gaze, and her sides were swelling – but by midnight she still hadn't given birth.

In the depth of the night they heard a noise in the barn.

“She's given birth!” the wife said in a confident whisper. “Our girl.”

Taking a torch, a little warmed by the liqueur they had drunk, they raced to see the mother.

They also had four goat kids, two male and two female, and fierce adult he-goat.

The husband could distinguish all his animals by the sound of their movement, and as he approached them he realized: the senior goat who was running from one corner of the pen to the other was not just excited, he was very scared.

The wife opened the door and screamed. She almost dropped the dim torch.

For the first time in her life, she managed to think about three things at once: the mother goat had given birth to the wrong kind of animal, the liqueur had been too strong, and this was the right time to cross herself, but the torch was in the way.

The husband, owing to his lack of vision, was not capable of being so scared.

Despite his blindness, he knew the positions of everything in his household. With an even movement he correctly found the switch and flicked it. The light came on.

As he listened, the husband realized that nothing so terrible was happening – all the animals were breathing, and so there had not been any killing: everything else seemed to be fixable to him.

“What's there?” he asked calmly.

The wife sighed and said:

“Lord… It's a dog. It's enormous. How did it get here?.. And the goat kids have been born… How do I get to them now…”

Shmel lay on the hay among the goats.

They were already used to him, and did not feel any menace from his presence. The male goat had first tried to butt him, but Shmel didn't mind and wasn't bothered. After a while the goats lay down next to the dog.

Shmel adored having someone warm lying and breathing next to him.

There was also a wonderful smell: milk, dung and new life.

Seeing the owners, he raised his head and waved his tail twice, as if asking a question.

“I'm not in the way, am I?” he seemed to be saying. “Don't worry, I'm looking after everyone…”

Every time his tail swept across the barn floor there was a rustling of dirty straw.

* * *

The grandchildren, although they were not blood relations, genuinely wanted to take their lonely ancient grandfather to town on every major holiday. He always refused.

On the last day of December, the grandfather heated the stove in the morning. In the evening he drank an infusion of summer herbs. He licked the wooden spoon with the honey stuck to it, long and carefully. He looked out the window, remembering that somewhere the first star would appear, which he could no longer see.

He climbed on the stove and waited for death.

Over the year death did not arrive, but perhaps it observed the calendar – and now it was visiting everyone whose documents in the general register were outdated or lost.

Until November the grandfather slept with the window open and did not fear the cold, but on New Year's Eve, to ensure that death would not encounter any obstacles, he left the door ajar, imagining what form it would take.

The grandfather did not believe that death looked like an old woman clutching a scythe. He was an old man himself – and how exactly could an old woman scare him, if he had outlived countless numbers of them in his life?

Half a century ago there was an old woman living in every hut, and the grandfather had buried all of them. The old women had daughters, and he had also buried many of them. Now the time of the granddaughters, but the grandfather no longer counted them.

Even if they all gathered together – how could he be scared of them?

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.