Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "The Harmony Silk Factory"

TASH AW

The Harmony Silk Factory

Dedication

For my parents

Contents

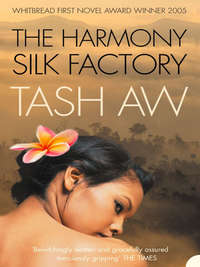

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Part One: Johnny

Part Two: 1941

Part Three: The Garden

P.S.Ideas, Interviews & Features

About the Author

About the Book

Read On

Praise

About the Author

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PART ONE Johnny

1. Introduction

The Harmony Silk Factory is the name of the shophouse my father bought in 1942 as a front for his illegal businesses. To look at, the building is unremarkable. Built in the early thirties by itinerant Chinese coolies (of the type from whom I am most probably descended), it is the largest structure on the main street which runs through town. Behind its plain whitewashed front lies a vast, cave-dark room originally intended to accommodate light machinery and a few nameless sweatshop workers. The room is still lined with the teak cabinets my father installed when he first acquired the factory. These were designed to store and display bales of cloth, but as far as I can remember, they were never used for this purpose, and were instead stacked with boxes of ladies’ underwear from England which my father had stolen with the help of his contacts down at the docks. Much later, when he was a very famous and very rich man – the Elder Brother of this whole valley – the cabinets were used to house his collection of antique weapons. The central piece in this display was a large kris, whose especially wavy blade announced its provenance: according to my father, it belonged to Hang Jebat, the legendary warrior who, as we all know, fought against the Portuguese colonisers in the sixteenth century. Whenever Father related this story to visitors, his usually monotonous voice would assume a gravelly, almost theatrical seriousness, impressing them with the similarity between himself and Jebat, two great men battling against foreign oppressors. There were also Gurkha kukris with curved blades for speedy disembowelment, Japanese samurai swords and jewel-handled daggers from Rajasthan. These were admired by all his guests.

For nearly forty years the Harmony Silk Factory was the most notorious establishment in the country, but now it stands empty and silent and dusty. Death erases all traces, all memories of lives that once existed, completely and for ever. That is what Father sometimes told me. I think it was the only true thing he ever said.

We lived in a house separated from the factory by a small mossy courtyard which never got enough sunlight. Over time, as my father received more visitors, the house too became known as the Harmony Silk Factory, partly for convenience – the only people who came to the house were those who came on business – and partly because my father’s varied interests had extended into leisure and entertainment of a particular kind. Therefore it was more convenient for visitors to say, ‘I have to attend to some business at the Harmony Silk Factory,’ or even, ‘I am visiting the Harmony Silk Factory.’

Our house was not the kind of place just anyone could visit. Indeed, entry was strictly by invitation, and only a privileged few passed through its doors. To be invited, you had to be like my father, that is to say, you had to be a liar, a cheat, a traitor and a skirt-chaser. Of the very highest order.

From my upstairs window, I saw everything unfold. Without Father ever saying anything to me, I knew, more or less, what he was up to and who he was with. It wasn’t difficult to tell. Mainly, he smuggled opium and heroin and Hennessy XO. These he sold on the black market down in KL for many, many times what he had paid over the border to the Thai soldiers whom he also bribed with American cigarettes and low-grade gemstones. Once, a Thai general came to our house. He wore a cheap grey shirt and his teeth were gold, real solid gold. He didn’t look much like a soldier, but he had a Mercedes-Benz with a woman in the back seat. She had fair skin, almost pure white, the colour of salt fields on the coast. She was smoking a Kretek and in her hair she wore a white chrysanthemum.

Father told me to go upstairs. He said, ‘My friend the General is here.’

They locked themselves in Father’s Safe Room, and even though I lifted the lino and pressed my ear to the floorboards I could hear nothing except the faint clinking of glasses and the low, muffled rumble which by then I knew to be the tipping of uncut diamonds on to the green baize table.

I waved at the woman in the car. She was young and beautiful, and when she smiled I saw that her teeth were small and brown. She was still smiling at me as the car pulled away, raising a cloud of dust and beeping at bicycles as it sped up the main street. It was rare in those early days to see expensive cars and big-town women in these parts, but if ever you saw them, they would be hanging around our house. None of our visitors ever noticed me, though, none but that woman with the fair skin and bad teeth.

I told Father about this woman and how she had smiled at me. His response was as I expected. He reached slowly for my ear and twisted it hard, squeezing the blood from it. He said, ‘Don’t tell stories,’ and then slapped my face twice.

To tell the truth, I had become used to this kind of punishment.

Even when I was young, I was aware of what my father did. I wasn’t exactly proud, but I didn’t really care. Now, I would give everything to be the son of a mere liar and cheat because, as I have said, that wasn’t all he was. Of all the bad things he ever did, the worst happened long before the big cars, pretty women and the Harmony Silk Factory.

Now is a good time to tell his story. At long last, I have put my crime-funded education to good use, and have read every single article in every book, newspaper and magazine that mentions my father, in order to understand the real story of what happened. For more than a few years of my useless life, I have devoted myself to this enterprise, sitting in libraries and government offices even. My diligence has been surprising. I will admit that I have never been a scholar, but recent times have shown that I am capable of rational, organised study, in spite of my father’s belief that I would always be a dreamer and a wastrel.

There is another reason why I now feel particularly well placed to relate the truth of my father’s life. An observant reader may sense forthwith that it is because the revelation of this truth has, in some strange way, brought me a measure of calm. I am not ashamed to admit that I have searched for this all my life. Now, at last, I know the truth and I am no longer angry. In fact, I am at peace.

As far as it is possible, I have constructed a clear and complete picture of the events surrounding my father’s terrible past. I say ‘as far as it is possible’ because we all know that the retelling of history can never be perfect, especially when the piecing together of the story has been done by a person with as modest an intellect as myself. So now I am ready to give you this, The True Story of the Infamous Chinaman Called Johnny.

2. The True Story of the Infamous Chinaman Called Johnny (Early Years)

Some say Johnny was born in 1920, the year of the riots in Taiping following a dispute between Hakkas and Hokkiens over the right to mine a newly discovered tin deposit near Slim River. We do not know who Johnny’s parents were. Most likely, they were labourers of southern Chinese origin who had been transported to Malaya by the British in the late nineteenth century to work on the mines in the valley. Such people were known to the British as ‘coolies’, which is generally believed to be a bastardisation of the word kulhi, the name of a tribe native to Gujarat in India.

Fleeing floods, famine and crushing poverty, these illiterate people made the hazardous journey across the South China Sea to the rich equatorial lands they had heard about. It was mainly the men who came, often all the young men from one village. They arrived with nothing but the simple aim of making enough money to send for their families to join them. Traditionally viewed as semi-civilised peasants by the cultured overlords of the imperial north of China, these southern Chinese had, over the course of centuries, become expert at surviving in the most difficult of conditions. Their new lives were no less harsh, but here they found a place which offered hope, a place which could, in some small way, belong to them.

They called it, simply, Nanyang, the South Seas.

The southern Chinese look markedly different from their northern brethren. Whereas Northerners have candle-wax skin and icy, angular features betraying their mixed, part-Mongol ancestry, Southerners appear more hardy, with a durable complexion that easily turns brown in the sun. They have fuller, warmer features and compact frames which, in the case of over-indulgent men like my father, become squat with the passing of time.

Of course this is a generalisation, meant as a rough guide for those unfamiliar with basic racial fault lines. For evidence of the unreliability of this rule of thumb, witness my own features, which are more northern than southern, if they are at all Chinese (in fact, I have even been told that I have the look of a Japanese prince).

I have explained that my ancestors probably came from the south of China, specifically from Guangdong and Fujian provinces, but there is one further thing to say, which is that even in those two big provinces, people spoke different languages. This is important because your language determined your friends and enemies. People in our town speak mainly Hokkien, but there are a number of Hakka speakers too, like my Uncle Tony who married Auntie Baby. The literal translation of ‘Hakka’ is ‘guest-people’, descendants of tribes defeated in ancient battles and forced to live outside city walls. These Hakkas are considered by the Hokkiens and other Chinese here to be really very low class, with distinct criminal tendencies. No doubt they were responsible for the historical tension and bad feeling with the Hokkiens in these parts. Their one advantage, often used by them in exercises of subterfuge and cunning, is the similarity of their language to Mandarin, the noble and stately language of the Imperial Court, which makes it easy for them to disguise their dubious lineage. This is largely how Uncle Tony, who has become a hotel tycoon (‘a hôtelier’ he says), managed to convince bank managers and the public at large that he is a man of education (Penang Free School and the London School of Economics), when really he is like my father – unschooled and really very uncultured. He has, to his credit, managed to overcome that most telltale sign of Hakka backwardness, which is the lack of the ‘h’ sound in their language and the resulting (and quite frankly, ridiculous) ‘f’ which comes out in its place, whether speaking Mandarin, Malay or even English. For example:

Me (when I was young, deliberately): ‘I paid money to touch a girl down by the river today.’

Uncle Tony (in pre-tycoon days): ‘May God in Fevven felp you.’

He converted to Christianity too, I forgot to say.

Johnny Lim was obviously not my father’s real name. At the start of his life he was known by his real name, Lim Seng Chin, a common and truly nondescript Hokkien name. He chose the name Johnny in late 1940, just as he was turning twenty. He named himself after Tarzan. I know this because among the few papers he left when he died were some old pictures, spotty and dog-eared, cut carefully from magazines and held together by a rusty paper clip. In each one, the same man appears, dressed in a badly fitting loincloth, often holding a pretty woman whose heavy American breasts strain at her brassière. In one picture, they stand on a fake log, clutching jungle vines; his brow is furrowed, eyes scanning the horizon for unknown danger while she gazes up at him. Behind them is a painted backdrop of forested hills, smooth in texture. Another picture, this time a portrait of the same barrel-chested man with beads of sweat on his shoulders, bears the caption, ‘JOHNNY WEISSMULLER, OLYMPIC CHAMPION’.

I’m not certain why Johnny Weissmuller appealed to my father. The similarities between the two are non-existent. In fact, the comparison is amusing, if you think about it. Johnny Weissmuller: American, muscular, attractive to women. Johnny Lim: short, squat, uncommunicative, a hopelessly bald loner with poor social skills. In fact, it might well be said that I have more in common with Johnny Weissmuller, for I at least am tall and have a full head of thick hair. My features, as I have already mentioned, are angular, my nose strangely large and sharp. On a good day some people even consider me handsome.

It was not unusual for men of my father’s generation to adopt the unfeasible names of matinée idols. Among my father’s friends, there have been: Rudolph Chen, Valentino Wong, Cary Gopal and his business partner Randolph Muttusamy, Rock Hudson Ho, Montgomery Hashim, at least three Garys (Gary Goh,‘Crazy’ Gary and one other I can’t remember – the one-legged Gary) and too many Jameses to mention. While there is no doubt that the Garys in question were named after Gary Cooper, it wasn’t so clear with the Jameses: Dean or Stewart? I watched these men when they visited the factory. I watched the way they walked, the way they smoked their cigarettes and the way they wore their clothes. Did James Dean wear his collar up or down in East of Eden? I could never tell for sure. I did know that Uncle Tony took his name from Tony Curtis. He admitted this to me, more or less, by taking me to see Some Like It Hot six times.

So you see, I was lucky, all things considered.

My father chose my name. He called me Jasper.

At school I learned that this is also the name of a stone, a kind of mineral. But this is irrelevant.

Returning to the Story of Johnny, we know that he assumed his new name around the age of twenty or twenty-one. Occasional (minor) newspaper articles dating from 1940, reporting on the activities of the Malayan Communist Party, describe lectures and pamphlets prepared by a young activist called ‘Johnny’ Lim. By 1941, the inverted commas have disappeared, and Johnny Lim is Johnny Lim for good.

Much of Johnny’s life before this point in time is hazy. This is because it is typical of the life of a small-village peasant, and therefore of little interest to anyone. Accordingly, there is not much recorded information relating specifically to my father. What exists exists only as local hearsay and is to be treated with some caution. In order to give you an idea of what his life might have been like, however, I am able to provide you with a few of the salient points from the main textbook on this subject, R. St J. Unwin’s masterly study of 1954, Rural Villages of Lowland Malaya, which is available for public perusal in the General Library in Ipoh. Mr Unwin was a civil servant in upstate Johore for some years, and his observations have come to be widely accepted as the most detailed and accurate available. I have paraphrased his words, of course, in order to avoid accusations of plagiarism, but the source is gratefully acknowledged:

• The life of rural communities is simple and spartan – rudimentary compared to Western standards of living, it would be fair to say.

• In the 1920s there was no electricity beyond a two-or three-mile radius of the administrative capitals of most states in Malaya.

• This of course meant: bad lighting, resulting in bad eyesight; no night-time entertainment; in fact, no entertainment at all; reliance on candlelight and kerosene lamps; houses burning down.

• Children therefore did not ‘play.’

• They were expected to help in the manual labour in which their parents were engaged. As rural Malaya was an exclusively agricultural society, this nearly always meant working in one of the following: rice paddies, rubber-tapping, palm-oil estates. The latter two were better, as they meant employment by British or French plantation owners. Also, on a smaller scale, fruit orchards and other sundry activities, such as casting rubber sheets for export to Europe, making gunny sacks from jute and brewing illegal toddy. All relating to agriculture in some form or another. Not like nowadays when there are semiconductor and air-conditioner plants all over the countryside, in Batu Gajah even.

• In the cool wet hills that run along the spine of the country there are tea plantations. Sometimes I wonder if Johnny ever worked picking tea in Cameron Highlands. Johnny loved tea. He used to brew weak orange pekoe, so delicate and pale that you could see through it to the tiny crackles at the bottom of the small green-glazed porcelain teapot he used. He took time making tea, and even longer drinking it, an eternity between sips. He would always do this when he thought I was not around, as though he wanted to be alone with his tea. Afterwards, when he was done, I would examine the cups, the pot, the leaves, hoping to find some clue (to what I don’t know). I never did.

• So rural children became hardened early on. They had no proper toilets, indoor or outdoor.

• A toilet for them was a wooden platform under which there was a large chamber pot. Animals got under the platform, especially rats, but also monitor lizards, which ate the rats, and the faeces too. A favourite pastime among these simple rural children involved trapping monitor lizards. This was done by hanging a noose above the pot, so that when the lizard put its head into the steaming bowl of excrement, it would become ensnared. Then it was either tethered to a post as a pet, or (more commonly) taken to the market to be sold for its meat and skin. This practice was still quite common when I was a young boy. As we drove through villages in our car, I would see these lizards, four feet long, scratching pathetically in the dirt as they pulled at the string around their necks. Mostly they were rock grey in colour, but some of the smaller ones had skins of tiny diamonds, thousands and thousands of pearl-and-black jewels covering every inch of their bodies. Often the rope would have cut into their necks, and they would wear necklaces of blood.

• Poor villagers would eat any kind of meat. Protein was scarce.

• Most children were malnourished. That is why my father had skinny legs and arms all his life, even though his belly was heavy from later-life over-indulgence. Malnutrition is also the reason so many people of my father’s generation are dwarfs. Especially compared to me – I am nearly a whole foot taller than my father.

• Scurvy, rickets, polio – all very common in children. Of course typhoid, malaria, dengue fever and cholera too.

• Schools do not exist in these rural areas.

• I tell a lie. There are a few schools, but they are reserved for the children of royalty and rich people like civil servants. These were founded by the British. ‘Commanding the best views of the countryside, these schools are handsome examples of the colonial experiment with architecture, marrying Edwardian and Malay architectural styles.’ (I quote directly from Mr Unwin in this instance.) When you come across one of these schools you will see that they dominate the surrounding landscape. Their flat lawns and playing fields stretch before the white colonnaded verandas like bright green oceans in the middle of the grey olive of the jungle around them. These bastions of education were built especially for ruling-class Malays. Only the sons of very rich Chinese can go there. Like Johnny’s son – he will go to one of these, to Clifford College in Kuala Lipis.

• There the pupils are taught to speak English, proper, I mean.

• They also read Dickens.

• For these boys, life is good, but not always. They have the best of times, they have the worst of times.

• Going back to the subject of toilets: actually, the platform lavatory continued to be used way into the 1960s. But not for me. In 1947, my father installed the first flush cistern and septic tank north of Kuala Lumpur at the Harmony Silk Factory. Before that, we had enamel chamber pots. My favourite one was hand-painted with red-and-black goldfish.

• So imagine a child like Johnny, growing up on the edge of a village on the fringes of a rubber plantation (say), tapping rubber and trapping animals for a few cents’ pocket money. Probably, he would have no idea of the world around him. He only knows the children of other rubber-tappers. They are the only people he would ever mix with. Sometimes he sees the plantation owner’s black motor car drive through the village on the way to the Planter’s Club in town. The noise of the engine, a metallic rattle-roar, fills Johnny’s ears, and maybe he sees the Sir’s pink face and white jacket as the car speeds past. There is no way the two would ever speak. Johnny would never even speak to rich Chinese – the kind of people who live in big houses with their own servants and tablecloths and electricity generators.

• When a child like Johnny ends up being a textile merchant, it is an incredible story. Truly, it is. He is a freak of nature.

• Unsurprisingly, many of the poor Chinese become communists. Not all, but many. And their children too.

Mr Unwin’s excellent book paints a vivid picture indeed. However, it is a general study of all villages across the country and does not take into account specific regions or communities. This is not a criticism – I am in no position to criticise such scholarship – but there is one thing of some relevance to Johnny’s story which is missing from the aforementioned treatise: the shining, silvery tin buried deep in the rich soil of the Kinta Valley.