Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Strangers"

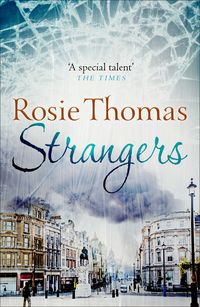

Strangers

BY ROSIE THOMAS

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in the United Kingdom by William Collins and Company 1987

Copyright © Rosie Thomas 1987

Rosie Thomas asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © MAR 2014 ISBN: 9780007560639

Version: 2018-09-24

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by Rosie Thomas

About the Publisher

One

It was just starting to snow.

Annie stood beside the row of coats hung untidily on the pegs and looked out of the glass panel in the back door. The dark grey specks fell out of a paler sky, and the wind caught them and blew them up into a spiral before letting them drop on the path. They changed from grey to white, and then vanished. In a minute, Annie thought, the flakes would stop melting. The snow would stick. She would need to wear her boots to go shopping. She opened the door of the cupboard under the stairs and rummaged for them, sighing as she always did at the sight of the tangle of family belongings. Then she took her coat off the peg, disentangling it from a red anorak with the sleeves pulled wrong side out.

A boy came down the stairs, two at a time, thumping his feet. He swung around the banister post and vaulted the last four steps down to the lobby. ‘Careful,’ Annie said automatically. ‘You’ll break a leg doing that, one of these days.’

The child looked squarely at her, and she knew that he was wondering how forcibly to contradict her. Then he shrugged. ‘No I won’t.’ He went to the door and pressed his face against the glass. ‘Look, Mum, it’s snowing. Can’t I come out with you?’ She buttoned up her coat and picked up her handbag, flipping through the contents to see if she had everything.

‘Can’t I?’

She smiled quickly at him, then glanced past him into the kitchen to see if her chequebook was on the table. She felt her attention being pulled two ways, fixing nowhere. It was often like that, nowadays.

‘No, you can’t. You hate shopping and you’ll only nag me to come home as soon as we’ve got there. And I’ve got a lot to do today.’

She found her chequebook in her coat pocket, and put it into her bag with her purse. The boy was sitting on the bottom step now, still staring longingly out at the snow. A thought occurred to him and he looked up at her.

‘Buying presents for me? For my stocking?’

His earnest gaze, a perfect replica of his father’s, made her smile.

‘That depends. And Tom, you may have grown out of Father Christmas, but Benjy hasn’t. You won’t spoil it for him, will you?’

Over the boy’s head she saw the snow beyond the window, falling faster now, powdering the garden wall with the faintest rim of white. Perhaps it would be a white Christmas. She breathed in the scent of pine needles, tangerines, log fires. ‘Okay,’ Tom said grudgingly. ‘He’s such a baby.’

Annie gathered up her scarf and gloves. There were a thousand things to be done before Christmas, faithful preparations for the family myth of a perfect holiday. She hugged Thomas and went to the foot of the stairs.

‘Martin? Where are you? I’m off now.’

There was a muffled thud from upstairs, two seconds of silence, and then the sound of a child’s full-throated yelling.

A moment or two later Annie’s husband appeared at the top of the stairs with Benjy in his arms. The little boy’s face was scarlet and crumpled, but he opened his eyes for long enough to make sure that his mother was watching. The crying went on undiminished.

‘He fell off the end of the bed,’ Martin said.

Annie ran up the stairs, already hot in her outdoor clothes. She rubbed Benjy’s head, feeling the round hardness of his skull under the silky hair. How resilient children are, she thought. Tougher sometimes than their parents.

‘Poor old Benjy,’ she said. Martin stood holding him, rocking him slightly, waiting for the noise to abate.

‘You’re going, then? What time will you be back?’

Martin was tall, with the rounded shoulders of someone used to stooping to reach the more general level. Annie was standing on the step below him and she had to stretch up to press her cheek against his. She didn’t see his face, but she noticed that the label was sticking out at the back of his jersey. He patted her with his free hand and Annie turned and ran back down the stairs.

‘What shall I give them for lunch?’ he called after her.

‘I don’t know. Look in the fridge for something, can’t you?’

The little ripple of domestic irritation washed after her all the way to the front door.

‘Or take them to McDonald’s, if you like.’

Thomas appeared in the kitchen doorway. ‘Yeah, McDonald’s. Dad? Are you listening? Mum said McDonald’s.’

Annie turned back to look at the three of them.

It wasn’t like Annie to turn back but today, for some reason, she did.

She saw Martin at the head of the stairs, his face so familiar that the features seemed to have been rubbed smooth, like a pebble by the sea. Benjy sagged in his arms, his head against his father’s shoulder. He had stopped crying, and his thumb was in his mouth for comfort. A few feet below them Thomas swung in an impatient arc from the newel post.

And all around them, like an over-detailed picture, the evidence of family life came crowding in. There was a broken plastic car overturned in the hallway, a dim grey line of handprints all along the shabby paint of the wall, a basket of clothes waiting to be ironed, on the hall table a sheaf of Polaroid snapshots of the boys.

‘What time will you be back?’ Martin repeated mildly. Annie’s irritation was disregarded. Sometimes it increased her annoyance, but she found herself smiling now.

‘I’m not sure. The crowds will be awful, probably. But I want to try and finish the last of the Christmas shopping today. Expect me when you see me.’

Annie opened the front door, and the cold wind blew in.

‘Bye,’ she called cheerfully. ‘See you all later.’

The door closed again. It was quiet outside. Not the muffled silence that came with snow, yet, but the quiet of waiting for it to happen. Annie ducked her head into the biting cold, and walked on down the path. As she opened the gate the Co-op milk float came round the corner, its little electric hum barely reaching her. Annie reckoned up quickly in her head, how many pints, and held up four fingers to the milkman. The snowflakes patted against her face. The milkman gave her a thumbs-up sign as the float stopped. Annie set off towards the station, walking quickly. She knew that it would take her exactly eight minutes. Martin hadn’t offered to drive her, even in the snow. They both knew without having to mention it that it was easier to walk than dress the children in outdoor clothes and persuade them into their car seats for the short drive. Annie was still smiling. That was the kind of telepathy bred by ten years of marriage, she thought, without bitterness.

As she turned the corner into the main road none of the few passers-by even glanced at her. Annie was just what she seemed, unremarkable, a housewife and mother intent on a day’s shopping. It would have taken a close look to reveal that she appeared a little younger than her real age, that her face was smooth even though her expression was preoccupied, and that she had an air of being capable, and content.

It was still early when Annie reached the first big store on her route for the day. The windows along the street blazed their Christmas displays at her. She looked at them for a moment, savouring the sight of satin ribbons and fir branches frosted with dry, sparkling snow. The real thing in the street outside was already grey-brown, spraying in filthy plumes under the wheels of the traffic. Annie pushed gratefully in through the big glass doors and breathed in the warm, perfumed air. She took her knitted hat off and shook her hair out, then turned towards the lift. She would start on the top floor and work her way down. Her list was ready in her coat pocket.

There was no one in the lift. She looked up at the indicator, congratulating herself on having arrived before the crowds. The doors opened at the top floor and she stepped out. A long counter heaped up with coloured balls faced her, red and green and silver and gold, and a pyramid of clear glass ones that held the iridescence of soap bubbles. She was drawn to the display and picked up a clear ball, turning it so that the colours changed in the light. Expensive, she thought regretfully. Nearly a pound each. But she took four, guiltily, putting them carefully into a wire basket. She moved across the department to the waterfalls of tinsel and buried her hands amongst the strands.

Two assistants waited at the nearest cash till.

‘What time d’you finish?’ Annie heard one of them ask.

‘Seven, tonight,’ her friend answered. ‘Makes the day seem endless, doesn’t it?’

The tinsel was coiled in Annie’s basket now, a bright silver serpent. They needed some new stuff, she reassured herself. Theirs was tarnished from too many annual appearances. But she wouldn’t spend any more money on decorations. She would go on down to the kitchen department and look for something for Martin’s mother. Her own mother needed a new dressing gown. She would go on to Selfridge’s for that, later. Annie’s face clouded as if she had remembered something painful, and she turned quickly with her basket towards the cash desk.

Yawning, one of the assistants wrapped up her purchases in green tissue. The other tapped the till keys and the electronic total flashed at Annie. She counted out the notes, picked up her carrier bag and walked towards the stairs at the back of the store. They were nearer than the lifts. She would walk down two floors. Heavy swing doors led to the stairwell. A sign over them announced Emergency Exit.

Annie reached the doors. She was vaguely conscious of someone else heading the same way. It was a man, he had been standing beside her at the cash desk, and now he was right behind her. She half turned her head, and his arm reached past to push the heavy door open for them both to pass through.

‘After you,’ the man said. She didn’t see his face. Nor did she ever say Thank you, although the words had formed in her head.

It was then that the bomb exploded.

It destroyed the staff cloakroom where it had been left overnight. It blew a hole up through the roof of the store, and the blast waves racing downwards into the heart of the structure ripped a great hole into which the floors tilted and fell. The terrible thunder of the explosion shook the surrounding streets and jolted the houses a mile away.

Annie didn’t hear a sound. There was an instant, an instant as long as infinity, when gravity deserted the world. In total silence she saw a blur of red and gold as the counter threw its load of glass balls into the whirling air, and then smashed them into fragments. She felt a silent wind that tore her clothes and flayed her skin and lifted her up only to pitch her forwards, down into a deathly pit where broken beams and chunks of wall boiled around her.

The fierce, white light was abruptly extinguished, and the dark descended.

The noise came then, like thunder receding, and in the wake of it came the roar of falling masonry as the store was sucked inwards on itself, molten, a whirlpool of stone and steel.

Annie fell, and went on falling, into the dark.

The noise had possessed her, but now it abandoned her again, growing fainter. The roaring crash was finished and in its place was the rattle of chunks of stone and plaster falling down on top of her. That grew fainter too, until it was only a whisper of dust, trickling into the crevices and settling as gravity took hold of the world again.

The girls at the cash desk were both dead. So was the cleaner who had been working in the cloakroom and who had lifted the tartan holdall out of its hiding place. Annie didn’t know it yet, but she was alive. She had fallen into the hole, with the heavy fire door half on top of her, like a shield.

Even the dust had stopped whispering now. The silence came again, long seconds, and nothing stirred. Then, up in the light, above the smoking rubble where tinsel and fragments of pretty glass were mixed with torn girders and other, terrible things, and where the snowflakes drifted and settled impartially, the first siren began to wail.

Annie couldn’t hear it. Her head thundered with the echo of the explosion and her eyes burned with the white flash of light. She closed her eyes, opened them again, but the glare was undimmed. Where had the dark gone? Her own, private darkness, how could that have been taken away? Were her eyes open or shut?

She lay without moving for a long time, she didn’t know how long. The roaring in her ears dropped in pitch, became muffled. The white blaze turned egg-yellow with a brassy point at the centre. The first bodily sensation to return was a wave of nausea. Annie tried instinctively to turn her head in order to be sick, but a sharp pain that seemed to be inside her head cut short the movement. She lay still again, staring up into the middle of the yellow glow. Slowly, like a fist unclenching, the nausea released its grip, and the light dwindled to a little point. Her eyes were opening and closing, she was sure of that now. It dawned on her that the light was inside her own head, and she could see nothing else because she was in utter darkness.

Annie’s tongue moved, finding her lips. They were coated with dust, except for one corner that was clogged with sticky moisture. There was the brackish taste of her own blood. She was suddenly possessed by panic, more powerful than the nausea. She tried to roll sideways, to draw her knees up into the foetal position, and found that she could not. She was hurt, badly hurt, and she was trapped in total blackness.

Annie could hear screaming, a scream that went on and on, up and then down again as the sufferer gasped for breath. When it stopped she wondered if the screams could have been her own.

Where was she? What had happened?

Oh God, please help me.

The screams had been hers. She could feel another one, the voice of pure terror, rising inside her. She clenched her teeth, and felt the grit crunch between them. She tried to swallow it, to clear her mouth, focusing on the smallest thing to keep the fear at bay. She could feel it all around her, like a living thing.

Think. Try to work out what had happened.

Slowly this time, she tried to move. Her right side, arm and shoulder right across to her breastbone, and her hip and thigh, wouldn’t do anything. She was pinned down by something smooth, sloping upwards at an angle. She discovered it by feeling cautiously upwards with her left hand. On her left side, higher up, there was something jagged that felt both hard and crumbling at the same time. She gave up her useless search and let her arm drop to her side again. Legs. Where were her legs? She could feel nothing at all in the lower part of them. It was as if her body was clay that had been crumpled up and crudely remodelled, stopping short at the knees.

And her head, the pain in her head. She rolled it, just a little, to one side and then the other. There was perhaps an inch or two of play before the pain gripped her. Suddenly Annie realized that her hair was caught underneath something. She had taken her knitted hat off – how long ago? – inside the doors of the shop. Now something very heavy was resting on her spread-out hair, and the pain she felt was the roots of it tearing her scalp. So even if there had been nothing else touching her she would still be trapped here by her hair, forced to lie staring upwards, into – into what?

There was only the pitch dark, not a sound except the threatening patter of falling fragments when she moved her arm. The fingers of her left hand fluttered, feeling the rough brick, splintered wood.

She was shuddering now, fully conscious, cold to her bones.

What would happen to her?

Annie screamed again as the fear lurched close and threatened to smother her. When the sound of it died away a voice said, very close to her, ‘Stop. Stop screaming.’

It wasn’t her own voice, she knew that. It was a man’s. A stranger’s.

At the sound of it, she remembered. Before the noise came, before even the silent wind and the shock that had spun her round into a rain of splintering glass balls, there had been a man. That was it. When she had still been Annie, walking calmly to the exit with a carrier bag of Christmas tree decorations, a man had come up behind her and pushed open the door. Out of the corner of her eye, in that last instant, she had seen his hand and arm.

Fear moved right inside her now. Where was the man, how close to her? Annie struggled to make her thoughts fit together.

He must have done this, whatever it was. And if he could do something so cataclysmic what else would there be, when he reached her? To stop the shuddering Annie bit her lips, and tasted salt blood again. She must keep still, or he would hear her. She lay with her head turned as far as it would go towards where the voice had come from, staring wildly into the impenetrable dark.

‘Where are you?’ he asked. ‘I don’t think I can reach you, but …’

‘If you come near me …’ Annie had wanted to scream at him, but her words were a gasp. ‘If you come near me, I’ll kill you.’

There was a long moment’s quiet.

Then the man said softly, ‘It’s all right. Listen, can you hear the sirens? They’ll reach us. They’ll get us out.’

A solitary policewoman had been standing on the opposite pavement, checking the number plate of a grey van parked on the double yellow lines. The side of it had sheltered her from the blast, and she crouched in the gutter for an instant with her cheek against the cold metal. She heard screaming, and the traffic skidding wildly in the roadway, and the crash of breaking glass. Slowly, sliding her hand up the van’s side, she stood up. Under a cloud of black smoke she saw the front of the store. The roof had been blown open to the sky and she could see the inside where the floors hung, pathetically exposed, tipping downwards. Chunks of brick were still falling. In the roadway people were running, some of them away from the falling bricks, others towards them. There were other people lying on the pavement.

The policewoman left the shelter of the grey van and made herself walk across the road. The broken glass crunched under her polished black shoes. She held up one black-gloved hand to stop the traffic, as she had been trained to do. Her other hand reached inside her coat for the pocket transmitter, to call for help.

The first squad car came, weaving up the street between the slewed cars and buses, its lights blazing. The policewoman was kneeling beside a man whose blood seeped through the clenched fist pressed to his cheek. There was suddenly an eerie quiet, and she thought how loud the siren sounded.

Two policemen leapt out of the car as it skidded to the kerbside. One of them carried a loudhailer, and he lifted it to his mouth.

‘Get back. Get back and stay back.’

One by one the people who had been milling on the pavement began to move slowly backwards, a step at a time. They were looking up at the ruined façade of the store where the smoke still drifted in black coils.

‘There may be a further explosion. Please leave the area at once.’

They moved a little further, leaving the injured and those who were helping them, bewildered groups on the littered pavement.

Down in the darkness the man’s voice repeated, insistent, ‘Can’t you hear them?’

At last, Annie said, ‘Yes.’

‘I can’t hear you properly,’ the man said louder. ‘Say it louder.’

She repeated, ‘Yes,’ and then, suddenly, ‘What have you done?’

There was quiet again after that, and she heard something moving, close to her. Her skin crept in a cold wave.

‘I didn’t do it.’ The voice sounded even closer now. ‘It must have been a bomb, I think. Perhaps a gas explosion.’

A bomb.

In her mind’s eye, imprinted on the terrifying darkness, the word conjured up flickering images. There were the television news pictures of violent death amongst the rubble, a half-forgotten impression of the reddened dome of St Paul’s still standing amongst the devastation of the Blitz, and then the mushroom cloud over Hiroshima.

A bomb.

The images faded and left her in the dark again. Her eyes stung with the effort of staring into it. She understood that a bomb had gone off, and buried her along with the broken Christmas tree balls, the gaudy strands of tinsel and the heavy door she had been going to push open. It was the same door lying on top of her now, crushing her.

Annie was shivering violently.

‘I’m afraid,’ she said.

She sounded very shocked, the man thought. But she was conscious, and she had stopped screaming. He wondered if there was a chance of manoeuvring himself close enough to help. He eased himself sideways a little, reaching out with his right hand.

‘What are you doing?’ Her voice was sharp with the onset of panic.

‘Trying to reach you. Listen to me, carefully. Where are you hurt?’

He could almost hear her thinking, painfully exploring the inner contours of her body, just as he had done himself.

At last she said, ‘I can’t feel my legs. My side hurts. There’s something heavy on top of me. I think it’s a door.’

‘That’s good. It’s probably like a shield for you.’

‘And my hair’s caught. I can’t move my head.’

She had long, thick fair hair. He remembered seeing it as she walked to the exit in front of him.

‘Can you move any part of you?’ he persisted.

‘My arm. My left arm.’

Gently, he said, ‘Reach out with it, then.’

He heard a tiny clink, perhaps the buckle of her watch against broken masonry, and the soft scraping of her fingers as they moved towards him. He stretched his own arm, further, until the muscles ached, and the splinters scraped his wrist. And then, miraculously, their fingers touched. Their hands gripped, palm to palm, suddenly strong.

Annie thought, Thank God. The hand in the dark was so solid, the feel of it gripping hers almost familiar, as if she already knew the shape of it.

The man heard the sob of relief in her throat. Her hand felt very cold in his.

‘What’s your name?’ he asked into the blackness.

‘Annie.’

‘Annie. I’ve always liked the name Annie. Mine is Steve.’

‘Steve.’

It was a reassurance to repeat the names, an affirmation that they were still there, still themselves after the cataclysm.

Annie felt his thumb move on the back of her hand, a little stroking movement. The fear began to loosen its grip, and her breath came easier. She turned her head towards him, as far as she could. Her hair pulled at her scalp.

‘I thought you did it,’ she said. ‘I’m sorry. I was afraid of you.’

‘I didn’t do it. I was just doing my Christmas shopping, like you.’

Christmas shopping … the translucent glass balls that had been so expensive, the shiny ribbons and fir branches in the shop windows, the snow falling in the wintry streets. And now? To be buried, in this acrid darkness. How far down? She had the impression that she had fallen down and down, into a great pit. What was balanced above them, how many tons of rubble cutting them off from the sky and air?

Annie’s hair tore at the roots as she struggled, involuntarily.

‘Keep still.’ Steve’s fingers tightened over hers.

Annie heard the door creak over her face. Yes, she must keep still.

‘And you?’ she asked. ‘Are you hurt?’

‘I’m cut, here and there. Not badly. My leg’s the worst. I think it’s broken.’

Now Annie’s fingers moved, trying to lace hers between his.

‘Don’t let go,’ Steve said quickly.

‘I won’t. I’m trying to think. How can we get out?’ She was collecting herself now, trying hard to keep her voice level.

‘I … don’t think we can.’ The sound of the sirens came again, multiplying, but a long way off. ‘They’ll come for us, Annie. It won’t be long, if we can just hold on.’

Annie thought, They won’t find us. How can they? No one even knows I’m here. I didn’t tell Martin where I was going.

‘Who is Martin?’

It was only with the question that Annie realized she had been thinking aloud. All her senses were dislocated. She was looking, staring so hard that her eyes stung, but she couldn’t see. There were noises all around her now, not just the sirens but other, rumbling sounds, creaking, and the rattle of falling fragments. Yet she couldn’t tell whether they were real, or replaying themselves inside her head, like her own voice. And suddenly she had the feeling that she wasn’t trapped at all, but falling again, spreadeagled in the blackness. Annie clenched her fists and tilted her face upwards, deliberately, ignoring the pain in her head, until her cheek met the solid, cold, weighty smoothness of the door.

‘My husband,’ she said, willing the words to come out normally. She wasn’t falling any more. ‘Martin is my husband.’

‘Go on,’ Steve said. ‘Talk to me. It doesn’t matter what. Lie still, and just talk.’

Leaving home this morning. There were the three of them, watching her go, little Benjy in Martin’s arms and Tom swinging around the banister post. Before that, she had run to the top of the stairs, reaching up to brush her cheek against Martin’s. A goodbye like a thousand others, hurried, and she hadn’t even seen her husband’s face. It was so familiar, rubbed smooth in her mind’s eye by the years.

Suddenly, Annie felt her solitude. She was going to die, here, alone. But the hand holding hers was blessedly warm. Where had Martin gone, then?

I love you. They repeated the formula often enough, not out of passion but to reassure each other, renewing the pledge. It is true, Annie thought. I do love him.

Yet now, trying to summon it up in pain and fear, she couldn’t see her husband’s face.

In its place she saw the garden behind their house, as vividly as if she was standing in the back doorway. Only a week ago. Martin was stooping with his back to her, his head half-turned, reaching for the hammer he had dropped on the crazy-paving path. She saw his hand, the torn cuff of the old jacket he wore for gardening, and heard the music coming from the kitchen radio.

They were working in the garden together. Martin had at last found time to repair the larchlap fencing that separated them from their neighbour’s voracious Alsatian. The boys had gone to a birthday party and they were alone, a rare two-hour interval of peace.

Annie was standing at the edge of the flower bed. The dead brown stalks of the summer’s anemones poked up beside her, acid with the smell of tomcats, and the earth itself was black and frost-hard. Her arms ached because she was holding up a bowed length of fencing, waiting for Martin to nail it in place. Neither of them spoke. Annie was cold, and Martin was irritable because he was an awkward handyman and the setbacks in the task had brought him close to losing his temper. He picked up the hammer and jabbed it at the nail, and the nail bent sideways. Martin swore and flung the hammer down again.

Annie was thinking back to the days when they had first bought the crumbling Victorian house, long before Tom was born. They had worked endless weekends, painting and hammering, because they couldn’t afford to employ builders or decorators. They would quarrel unrestrainedly then, launching themselves into blazing arguments over the coving that had been mitred wrong, the glaringly mistaken shade of paint, the tiled edge that rippled like waves on a lagoon. And then they would stop, and laugh about it, and they would go upstairs and make love in the bedroom where the last occupants’ purple and orange wallpaper hung down in ragged strips over their heads. Nine, ten years ago.

A similar memory must have touched Martin too. He had kicked the hammer aside and straightened up to look at her.

Annie saw his face now, every line of it. She could have reached up and touched it in the darkness. He looked almost the same as he had when they first met, except for the deeper creases beside his mouth, and his frown.

He had put his arms round her, inside her coat, and kissed her.

‘Let’s ask Audrey to come in tonight, so that we can go and eat at Costa’s.’

They always went to Costa’s. Annie couldn’t remember the last time they had been anywhere else. They shared a plate of hummous, and then they had dolmades and a bottle of retsina. The last time, after their work in the garden a week ago, they had come in late and Martin had taken the babysitter home. Annie had gone on up to bed and she had fallen asleep at once, before he lay down beside her. In the morning Benjy had woken at six, and for the sake of another hour’s peace she had carried him in and put him between them. He had smiled in triumph, with his thumb in his mouth.