Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

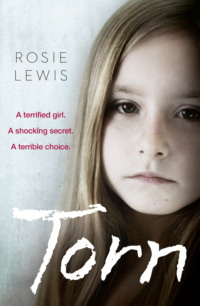

Buch lesen: "Torn: A terrified girl. A shocking secret. A terrible choice."

Copyright

Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the family’s privacy.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperElement 2016

FIRST EDITION

© Rosie Lewis 2016

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover photograph © Vanessa Skotnitsky/Arcangel Images (posed by model)

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

Rosie Lewis asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

Source ISBN: 9780008112974

Ebook Edition © January 2016 ISBN: 9780008112981

Version: 2015-11-17

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

By the same author

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Epilogue

Sample chapter of Skin Deep by Casey Watson

Also available

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

About the Publisher

By the same author

Helpless

Trapped

A Small Boy’s Cry (e-short)

Two More Sleeps (e-short)

Betrayed

Unexpected (e-short)

Prologue

Taylor hates weekends.

All she keeps whispering, over and over as she tiptoes around the house, is, ‘Come on, Monday, please come on.’ She doesn’t think anyone in the whole world wants Saturday to be over as much as she does. Dad’s eyes are on fire, like they’re about to explode. Mum’s lips have been white all day, pinched together like when there’s a sad bit on the news. She keeps picking things up, looking confused and then putting them down again.

Taylor knows something bad is going to happen; she can always tell. She glances from Dad to Mum, trying not to catch a glimpse of the spots of red on the carpet – her tummy goes funny when she remembers how they got there. Her little brother, Reece, huddles next to her on the sofa, his knees scrunched right up to his chin. He’s been crazy all day, grovelling around everyone and trying to please them. It makes Taylor sick.

She can’t wait to go to bed but it’s not even six o’clock. Jimmy, their Labrador, pads over and rests his chin on her lap. Every time one of them moves the puppy makes a noise, a sort of cross between a growl and a whimper. Taylor buries her face into his soft fur and cups her hand over his muzzle. ‘Shush, there’s a good boy, shush.’ When she looks up she sees that Mum has stopped tidying. She’s standing in front of them, a strange look on her face.

Taylor’s heart beats faster.

Dad hovers and, moving in slow motion, Mum starts tidying again, even though there’s nothing left to put away. Reece rubs his nose and sniffs. Taylor can feel his leg trembling.

Her eyes skirt slowly around the room. Things are definitely about to blow, she can feel it. Pretending to be calm, she tries to plan an escape route in her head like that girl in the Hideout cartoon, but it’s much harder than the website makes out. The front door is locked and she doesn’t know where the keys are. It occurs to her that one of the windows upstairs might be open, but then she remembers that Bailey is still in his cot and there’s no way she’s going to make a run for it without her baby brother. Oh, why can’t she think of something?

The wind blows outside the window and Taylor hears a clomping sound: footsteps on the pavement. Someone is walking past their house like none of this is going on. How can things carry on as normal, Taylor wonders, when everything is so wrong? Jimmy hears it too. His ears prick up and he jumps to his feet, barking. Mum’s head shoots round. Reece’s knees knock together.

For one hopeful second Taylor considers calling out for help but Jimmy starts howling and she freezes. His tail is buried so far between his legs that she can hardly see it. Keeping Mum in sight, Taylor edges closer to Jimmy and wraps her arms around his neck. ‘Please, Jimmy,’ she whispers, ‘it’s all right. Please don’t.’

Jimmy pulls away. He leaps around in circles, snapping at the air. Mum sways on her feet, her eyes flitting over the three of them. Taylor knows one of them is about to pay but she isn’t about to stand by and let her family get hurt, not again. She’s ten years old now and she’s been learning how to fight.

Ignoring the sick feeling in her tummy, she takes a deep breath and forces herself to her feet.

Chapter One

Maisie Stone eased the end of a biro between the wiry roots of her thick auburn dreadlocks, half-closing one eye as she twirled it around. Turning the radio on to mask our conversation, I reflected that the social worker wasn’t exactly what I’d envisaged when we’d spoken earlier that day, but then neither were the siblings waiting miserably upstairs in the spare room.

‘So, Rosie, this is kind of awkward,’ Maisie lisped, the words rolling over her silver-studded tongue so slowly that it was as if she needed winding up. Over the telephone she had spoken with such slow deliberateness that in my head she was nearing retirement. The woman sitting in front of me, with a thin leather bandana tied around her hair and taffeta skirt skimming her sandalled feet, had taken me completely by surprise. With her full lips and wide green eyes, there was an earthy appeal about Maisie, but the skin beneath her eyes was swollen and dotted with blemishes. By the way she was dressed I guessed she was in her early thirties at most, but somehow she seemed much older. Either that or she hadn’t slept in days. ‘When I picked them up I couldn’t believe there was one of each.’

‘You’d never met them before?’

Maisie’s beaded dreadlocks jingled as she shook her head. ‘No, their file landed on my desk at half past ten this morning. I only had time for, like, a quick flick through and when I saw Taylor described as a massive Chelsea fan I just assumed, what with her name and everything –’ her words trailed away and then she groaned, pulling her hands down her face. ‘Is there any way you could, like, jiggle things around to make it work?’

It was the look of open appeal on her face that really got my sympathy going. ‘Well, maybe there is a way,’ I said, my mind still clawing through possible solutions as I spoke. According to my fostering agency’s rules, only the under-fives or same-sex siblings were allowed to share a room. Since Taylor and Reece fitted neither category, they needed a foster carer with two spare bedrooms.

‘And you’re sure you don’t mind?’ Maisie asked a few minutes later, her eyes, if not bright with relief, then at least a little less puffy than they had been.

‘Oh, it’s not really a problem,’ I answered, in a not quite convincing tone. I wanted to help and so had offered to convert our dining room into a temporary bedroom for myself. On a practical level it made sense – Taylor and Reece were already here and it was a bit late in the day to start hunting for a new placement for them – but the thought of dismantling the dining table and then dragging my own double bed downstairs wasn’t very appealing.

‘Cool,’ the social worker said, the thick wooden bangles on her wrists knocking together as she scratched the other side of her scalp. ‘We prefer children to stay at their own school if at all possible, and the only other carer matching their profile lives, like, forty miles away.’

‘Ah, I see,’ I said, my eyes narrowing. When social workers were desperate to place children, all sorts of cunning ruses came into play. I was beginning to wonder whether there really had been a mix-up over Taylor’s sex when the rise and fall of frenzied conversation drifted down the stairs. The noise brought my thoughts firmly back to the children and I decided to focus on the positives. With a nationwide shortage of foster carers, siblings were still sometimes separated. At least, in this instance, they could stay together. The base of my bed came in two halves so hopefully it wouldn’t be too heavy to lift and, compared with the upheaval Taylor and Reece were going through, moving a bit of furniture wasn’t too much of a hardship. ‘What’s their history?’ I asked, setting my suspicions aside. I knew that five-year-old Reece had made a disclosure to his teacher earlier that day, but that was about all.

Maisie blinked several times. She seemed to be struggling to summon the energy to speak. ‘So, as I said, I haven’t had a chance to go through their entire file yet but it seems that the children have been registered as “in need” for years. Their regular social worker is on long-term sick and I’ve only just inherited the case, but from what I can make out, a few incidents of domestic violence have been flagged up to us by police. Nothing too serious, but Dad is long-term unemployed and when you add Mum’s depression into the mix –’

Maisie’s sentence trailed off and I nodded, unsurprised. It was the spring of 2005 and although I had only been fostering for a couple of years, I had already noticed a common theme of domestic violence among the families of looked-after children. The violence was often accompanied by parental depression and substance abuse, a set of issues labelled by social workers as ‘the toxic trio’. When all three ‘markers’ were present, children were feared to be most at risk of severe harm.

‘Unfortunately, Taylor, the eldest, has been replicating the violence at school,’ Maisie said, snail-like. ‘I’m told that most of her classmates want nothing to do with her.’

‘Oh dear,’ I said, pressing my lips together. It was natural for Taylor to use her personal experiences as a template for relating to others. The poor girl was probably suffering as much as the children she was bullying, although I knew that was a view that could be unpopular, particularly with parents of the victim.

Maisie leaned back into the sofa and sipped from a can of Red Bull. It was her second since she’d arrived and I couldn’t help but wonder what she would be like without all that caffeine, if this was Maisie on fire. ‘As you probably know, Rosie, we have a duty of care to keep children within their own family if at all possible. It looks like all sorts of intervention therapies have been offered but the Fieldings have refused to engage with any of them.’

Longing to get upstairs and help the children to settle in, I reached for the nearest cushion, planted it on my lap and fiddled with the tassels. Being plucked from one life and planted in another one was a shock for anyone and the siblings were probably still reeling. Of course, there were some things that Maisie needed to tell me in private, but her drawl was agonisingly slow. ‘What did Reece disclose?’

‘So, Reece’s teacher noticed a red mark on his thigh as the class were changing for PE this morning. At first he made out that he’d been stung –’

I grimaced, amazed at the lengths children went to in defending parents who offered little protection in return.

‘I know, sweet, yeah? But when pressed, he admitted that his mother had slapped him. Mum’s insisting that it was just a little tap but there’s a mark, like,’ Maisie cupped her hands together in the shape of a rugby ball, ‘this big on his thigh.’

I sighed, my heart going out to him. It was March and the Easter holidays were only a few days away. There was often an influx of children coming into care when school holidays loomed – children seemed more able to cope with problems at home with the daily security of school to escape to but the prospect of losing that safety net sometimes drove them to reach out to their teachers for help. As a consequence, more disclosures were made in July and December than at any other time of the year.

‘School says that Mum’s really dedicated to the children so we’re leaving Bailey with her for the moment. There have been concerns about him since birth, mainly due to Mum’s mental health issues, but she’s on medication for her depression and things have been stable for a while, until this happened of course. We’re going to need to keep a close eye on things.’

‘Bailey?’

‘Oh, yeah, course, you don’t know that yet. He’s the youngest, fifteen months or so.’ Maisie took another sip of the energy drink. ‘We’re holding an emergency strategy meeting tomorrow to discuss what to do about him. For now, the parents have agreed to a Section 20 for Taylor and Reece.’

If children were removed from their parents under a Section 20, Voluntary Care Order, their parents retained full rights, at liberty to withdraw consent to foster care at any time. Reluctant families sometimes went along with a voluntary plan because they felt that they had more control over what happened to their children.

As Maisie finished her drink, I found myself wishing I had more space at home so that little Bailey could join us, should he need to come into care. Having recently attended a child protection course, I knew that on average over the past two years in the UK, more than one child a week lost their life at the hands of a violent parent. It seemed to me that social workers had a delicate balancing act on their hands in trying to ensure that the welfare of the child was paramount.

One of Douglas Adams’s dictums suddenly came to me. He said, ‘The fact that we live at the bottom of a deep gravity well, on the surface of a gas-covered planet going around a nuclear fireball 90 million miles away and think this to be normal is obviously some indication of how skewed our perspective tends to be.’ When a child is taken into care, the course of their life is sometimes changed for ever and I’ve often wondered how social workers set the bar of negligence objectively, in the absence of a definitive answer. I was just glad that the task of making such far-reaching decisions was outside of the remit of a foster carer’s role.

A loud scream from upstairs interrupted my thoughts. Maisie blinked and looked at me. I jumped to my feet and ran into the hall. ‘Are you all right up there?’ I called, taking the stairs two at a time.

Chapter Two

‘It weren’t me,’ Taylor said, touching her hand to her chest. Straight away my eyes were drawn to her fingernails, painted a dazzling strawberry red. Sitting on the single bed nearest the door, she flicked her waist-length, burnished blonde hair over one shoulder and blinked belligerently. Five-year-old Reece, whey-faced and hesitant, hovered in the middle of the room chewing his bottom lip. ‘W-w-what’s going on? Where we sleeping?’ he asked, his face a picture of uncertainty. He dragged a knuckle across one eye, dislodging the black-rimmed spectacles he wore so that they fell across his cheek. ‘W-w-where’s Mummy?’

‘Well, that’s what Maisie and I have been discussing,’ I said, the disembodied screams already drifting to the back of my mind. The social worker entered the room at that moment, stopping just inside the door. She rested her back against the wall with a sigh, as if the task of climbing the stairs had drained the last dregs of her energy. ‘We’ve decided that, Reece, you can have this room and, Taylor,’ I turned to the ten-year-old, ‘you’ll be in a room just down the hall. I expect Maisie will fill you in on when you can see your mum. Isn’t that right, Maisie?’

She nodded. ‘Yeah, sure. That’s something I need to discuss with Mummy first though.’

‘But there are t-t-wo beds in here,’ Reece said, screwing his eyes up and then blinking rapidly in what appeared to be a nervous twitch. ‘What one’s mine?’

‘Either one,’ I told him, smiling reassuringly. ‘We’ll decide later shall we?’

He looked horrified at that, his mouth falling open in shock. Despite possessing the appearance of a miniature bouncer, with his closely cropped mouse-brown hair, broad forehead and stocky chest, I got the sense that Reece would need lots of reassurance to cope with being thrust into such an unfamiliar situation. ‘Tell you what,’ I said gently, walking over to the bed beneath the window and perching on the edge. ‘This bed is comfy. Would you like to sleep here?’

For a split-second his features relaxed but then his thick eyebrows contracted, his amber-brown eyes pooling with tears. The fine lower lashes glistened, darkening his eye sockets so heavily that they appeared bruised. ‘I want Mummy,’ he cried, toddler-like. He clutched his midriff. ‘Ow, I got a tummy ache now.’

‘Aw, I know, honey. It’s all a bit overwhelming isn’t it?’ I held out my hand and he shuffled a few tentative steps towards me, lower lip trembling.

‘Oh, for God’s sake,’ Taylor mumbled, running her fingers through her hair and clamping it in a fist at the top of her head. The V of a sharply defined widow’s peak stood on show momentarily, until her hand dropped to her lap, her cheeks ballooning with a loud, huffing breath. Humiliated, Reece froze, mid-step. After a swift glance at his sister, he bent one knee and stretched his arms up over his head, as if he’d been planning to warm up his muscles. Taylor rolled her eyes and lifted her trainer-clad feet onto the bed. I felt a tightening in my stomach – a longing to slip an arm around Reece’s shoulder and reassure him that he was safe.

I smiled at him instead and then turned to his sister. ‘Not on the sheets please, Taylor.’ Still in the infancy of my fostering career, I felt awkward imposing discipline on a child I had only just met, but caring for Alfie, a little boy with a penchant for biting, had honed my conviction that early firmness paid off. When the three-year-old had first arrived at our house, skinny and bruised, I felt such sympathy for him that I had allowed him to rampage through the house unbridled. It took five weeks to regain control, during which time we were all thoroughly miserable. I wasn’t about to make the same mistake again.

Taylor tutted and heaved a heavy sigh but, I was relieved to see, kicked her trainers off using the edge of each foot. Sockless, her toenails were painted a deep maroon, the colour complementing her painted fingernails. I lifted my hands up and clapped them softly together. ‘Great, thank you. We’ll move the bed you’re sitting on after we’ve had dinner and then you can see your room. Is that OK?’

She lifted one shoulder in a half-hearted shrug and I took a long assessing look at her, trying to work out whether I was sensing an attitude or poorly disguised shyness. Something in her stance emitted an air of reckless disregard and my thoughts were suddenly touched by Riley, a fourteen-year-old lad who came to us as an emergency placement the previous year. Tossed aside by his alcoholic mother and excluded from school, his life before coming into care was disorganised and traumatic, stripped of all that was gentle. New to fostering at the time, it took me a few days to realise that living dangerously close to the edge was Riley’s own dysfunctional way of coping with the implacable truth that no one cared. Heartbreak, I came to realise, was most often the cause of bad behaviour.

Riley was only with us for three weeks and moved on to a married couple in their early sixties. I was recently startled to hear them proudly announcing that Riley was studying hard for his GCSEs with the ambition of becoming a police officer as soon as he was old enough. Bearing in mind that Riley used to remove the shells from snails and then set light to them, the transformation was remarkable.

Of slighter build than her brother, Taylor put me in mind of a young Hayley Mills. There was definitely more than a passing resemblance there, in her rosy pout, fair skin sprinkled with freckles and deep-blue eyes. Her clothes were anything but 1950s though – she was wearing a navy velour tracksuit top and tight cropped jeans. Even from across the room I could see that they were expensive.

Physically speaking, it was easy to see that the siblings were related, but the similarities seemed to end there. Where Reece seemed highly strung and agitated, Taylor came across as confident, cocky even. But it was early days and children rarely presented their true selves when surrounded by unfamiliar people. According to Maisie, the siblings had been expecting a late-afternoon shopping trip with their mum. It must have been an unpleasant shock to find an unfamiliar social worker waiting for them in the headmistress’s office at the end of the school day. To make matters worse, I had been so surprised to find a boy and girl on my doorstep that my intended warm welcome evaporated as soon as I laid eyes on them. Quickly recovering, I had hoisted a smile back on my face, but, as I was to appreciate in the coming weeks, first impressions stick.

‘OK, good.’ I turned to Maisie and raised my eyebrows, waiting for some input. Eyes watering, she blinked several times, then looked at me expectantly. I got to my feet. Clearly I was going to have to take the lead. ‘Right, shall we go downstairs, then?’

The doorbell rang before I’d reached the bottom stair. Taylor, who had been whispering insistently in her brother’s ear since leaving the bedroom, suddenly clamped a protective hand on his shoulder, holding him back. ‘Who’s that?’ she demanded, sounding thoroughly displeased with the unexpected development.

‘Emily and Jamie I expect,’ I said, glancing back at Taylor. The ghost of a fearful expression lingered on her face. Swiftly, she replaced it with one of disgruntlement but not before I’d noticed. I paused on the stair for a split-second, registering a swell of compassion for her. Beneath her surly exterior was deep unhappiness – I could sense it – no matter how much hubris she managed to project. Reaching it wasn’t going to be easy, I was almost certain of that and as I opened the door another thought fleetingly occurred to me – just what had she been drilling her brother about in such an urgent tone? ‘Ah, yes, here they are!’

My ex-husband, Gary, stood behind Emily, our daughter, who was ten at the time and our seven-year-old son, Jamie. The air around them was damp with misty rain, the sky a stormy grey.

‘Hi,’ Gary said, surprising me with his distant tone. After separating three years earlier, when I was thirty-one, our first year apart had been turbulent. Each of us unsure how to behave, we had passed the children awkwardly between us, something we never dreamed would happen when we first held them in our arms. The trouble was, there seemed to be no raft for fledgling divorcees to grasp on to, no chart to navigate our way out of enemy territory. It took a while to find but eventually, with joint relief, we anchored ourselves in a place of calm, even salvaging a friendship of sorts.

Now though, Gary, five years older than me and craggier, in a handsome way, with each passing year, was bobbing from foot to foot as if cold. Craning his neck, he looked beyond me, into the hall. When my gaze drifted over the top of his head, the uncharacteristic formality made sense – his new partner, Debbie, was waiting in the passenger seat of his car, staring towards the house. Debbie was uninvolved in the ending of our marriage but, somehow, in my not quite healed mind, she was guilty by association. Dark haired and attractive, Debbie smiled when our eyes met. I lifted my hand in a wave, about as much interaction as any of us could take, I think, and it was a relief when the light rain escalated into a deluge. Gary, I noticed with stifled amusement, appeared equally thankful. After ruffling Jamie’s hair and touching a thumb to Emily’s cheek, he dashed off to the car.

Characteristically bypassing introductions, Jamie bundled into the house first, pulling up short at the bottom of the stairs. I had called Gary earlier and asked him to update Emily and Jamie on the placement before they arrived home. They loved being part of a fostering family but I wasn’t sure how they’d feel if they found two similarly aged children making themselves comfortable without prior warning. ‘You’re five,’ Jamie told the bewildered boy who had taken my place on the first stair.

Reece screwed his eyes up again and then glanced at his sister, as if checking it was safe to confirm such personal information. Taylor raised her eyebrows a fraction and gave a little shrug, body language Reece seemed to interpret as a green light. He turned back to Jamie and nodded.

‘And this is Taylor,’ I said, gesturing towards the stairs with a nod. ‘She’s ten.’

Jamie, wiping drops of rain from his forehead with the back of his hand, was about to respond when Taylor took the lead: ‘I can’t stand boys,’ she said, her lip curled upwards in a nasty sneer. ‘I literally hate ’em.’

My son stared at her for a moment then glanced at me with a puzzled expression. ‘Um, your greeting could do with a little tweaking, Taylor,’ I said, trying to make light of it. ‘That’s something we’re going to have to work on, I think.’

‘Wha-t?’ Taylor asked. From her tone it was as if I’d suggested that she sprinkle the hallway with rose petals and throw herself at my son’s feet in welcome. Still perched on the second stair, she was looking down on me with disdain.

‘We’ll discuss it later,’ I told her. Jamie, seemingly unaffected by Taylor’s emphatic declaration, plonked his school bag at my feet and scooted off to the living room. Clearly expecting his new, less frosty housemate to follow, he called out, ‘What year are you in?’ Reece, who seemed to have forgotten all about his tummy ache, trotted after Jamie.

‘One,’ he shouted behind us, repeating it several times until Jamie made a noise of acknowledgement.

In the living room, Jamie had already separated some Lego into two piles and was directing Reece to start work on the base of a helicopter. Maisie took a seat behind them on the sofa, her gladiator sandals almost touching one of the empty cans of Red Bull lying on the carpet. Emily, her blonde hair glistening with rain, hovered uncertainly at the door. Her eyes followed Taylor with interest as the ten-year-old strode from room to room. My chest tightened as Taylor sat herself down in front of the computer and switched it on without even asking. It was natural for her to want to explore her new surroundings but there was something proprietary in her manner that irked me. It was difficult to imagine Taylor and Emily hitting it off as Jamie and Reece already seemed to have done – Emily was quite a gentle soul and I got the sense that Taylor was a girl who liked to rule the roost.

I was about to tell Taylor that she needed to check with me before using the computer when Maisie held out some papers on a clipboard. When children come into care, their foster carer is expected to sign a placement agreement; a form setting out what is required of them as well as essential information about the children, medical consents and contact arrangements. Since the placement had been arranged in a hurry, much of the form was still blank. After scribbling my signature at the bottom of the last page, a noise from the kitchen drew my attention. Taylor had sauntered past us and opened the fridge. She was standing in front of it, perusing the contents. ‘Oh, Taylor, what are you looking for?’

‘Food,’ she said with a sniff. ‘God, isn’t that obvious?’ she added, her head so far into the fridge that her voice was muffled.

‘OK, but tell you what – you let me know what you’d like and I’ll get it for you.’ I balanced the clipboard on top of a bookshelf and walked through to the kitchen. ‘Excuse me please, love,’ I said mildly, ignoring her icy stare. ‘Would anyone else like a biscuit or something? Maisie? Tea, coffee?’

For the first time since her arrival, Maisie seemed alert. ‘Nothing for me thanks,’ she said slowly, sitting forwards on the sofa. She was watching us avidly and half an hour later, as the social worker roused herself to leave, I discovered why. ‘OK, so, can I just ask you something, Rosie?’ she said as she stood in the hall, lifting a large, embroidered handbag and resting the strap on her shoulder.

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.