Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

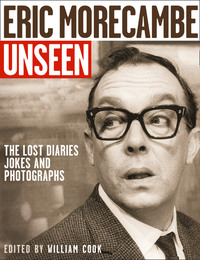

Buch lesen: "Eric Morecambe Unseen"

William Cook

ERIC MORECAMBEUNSEEN

THE LOST DIARIES JOKES

AND PHOTOGRAPHS

COPYRIGHT

HarperNonFiction

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2005

Copyright text © William Cook 2005

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007234653

Ebook Edition © MAY 2019 ISBN: 9780008363451

Version: 2019-05-16

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

NOTE TO READERS

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780007234653

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

NOTE TO READERS

PART ONE LIFE & WORK

Chapter 1 HARPENDEN

Chapter 2 MORECAMBE

Chapter 3 BARTHOLOMEW & WISEMAN

Chapter 4 MORECAMBE & WISE

Chapter 5 THE VARIETY YEARS

Chapter 6 THE ATV YEARS

Chapter 7 KEEP GOING, YOU FOOL!

Chapter 8 THE BBC YEARS

Chapter 9 THE THAMES YEARS

Chapter 10 BRING ME SUNSHINE

Chapter 11 WHAT DO YOU THINK OF IT SO FAR?

PART TWO JOKES & JOTTINGS

Chapter 12 UNFINISHED FICTION

Chapter 13 THE DIARIES (1967)

Chapter 14 THE DIARIES (1968)

Chapter 15 THE DIARIES (1969)

Appendix 1 ONE LINERS

Appendix 2 ERIC’S NOTEBOOKS

Appendix 3 NOTES

Appendix 4 BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Chapter 1

HARPENDEN

Ernie: What’s the matter with you?

Eric: I’m an idiot. What’s your excuse?

AT FIRST GLANCE, the house doesn’t look like much – not from the main road, at least. It’s detached but fairly modern, built of unpretentious brick. The front lawn is neat but nondescript. Most of the garden is around the back. There’s a friendly Alsatian dozing in the drive. She sits up but doesn’t bark. There’s an outdoor swimming pool, but it’s purely functional, not fancy. In fact, the most remarkable thing about this house is that there’s nothing remarkable about it. It’s a place you’d be pleased to live in, but it’s hardly the sort of place you’d associate with one of the greatest comedians who ever lived.

Eric Morecambe’s house in smart, respectable, suburban Harpenden is a lot like the brilliant comic we all knew – or thought we knew – and loved. From the moment you arrive, it feels strangely familiar. Even on your first visit, it seems like somewhere you’ve been coming all your life. ‘It wasn’t a show business house,’ says Eric’s old chauffeur, Mike Fountain, who comes from Harpenden. ‘It was a family home.’ And it still is. Like Eric, it feels safe and comforting, without the slightest hint of ostentation. And from 1967 until his untimely death in 1984, it was the home of a man who, more than anyone, summed up the Great British sense of humour.

Britain has always been blessed with more than its fair share of comedians, but there’s never been another comic we’ve taken so completely to our hearts. Peter Cook, Peter Sellers, Tony Hancock, Spike Milligan – these were comics we adored, but there was always something remote, almost otherworldly, about them. We laughed at them rather than with them. Sure, we found them funny – but secretly, we thought they were rather strange. Eric Morecambe was awfully funny, but there was nothing remotely strange about him. To millions like me, who never knew him, he was like a favourite uncle, with a unique gift for making strangers laugh like old friends.

More than twenty years after he died, from a heart attack, aged just 58, Eric’s irrepressible personality still lingers in every corner of his comfortable home. There’s a framed photograph on the piano of him hobnobbing with the Queen Mother, and for a moment you wonder how on earth Eric, our Eric, got to meet the Queen Mum. But then you see a photo of Ernie Wise alongside it, and you remember. He wasn’t our Eric at all – that was his great illusion – but half of Britain’s finest, funniest double act, Morecambe & Wise.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, Morecambe & Wise were the undisputed heavyweight champions of British comedy. Christmas was inconceivable without their TV special. Their fans ranged from members of the Royal Family to members of the KGB. Their humour was timeless and classless, and that was what made them irresistible. They were stylish yet childlike, and they united the nation unlike any other act, before or since. You could laugh at Eric if you were seven. You could laugh at him if you were seventy. Old or young, rich or poor, you couldn’t fail to find him funny. He didn’t seem like a celebrity. He felt like one of the family, which is why it feels so normal to be standing here, in the cosy house where he used to live. Eric once said he wanted daily life here to be as average as possible, and funnily enough, it still is. ‘The overwhelming impression I formed of Eric,’ says his old friend Sue Nicholls, better known to the rest of us as Audrey in Coronation Street, ‘is just how ordinary he was.’1 Yet this ordinary man had an extraordinary talent, and the most extraordinary part of it is how ordinary he made it seem. As his wife, Joan, says, with simple clarity, ‘He was one of them.’

Joan still lives here, just like she used to live here with Eric. She’s never remarried, and she has no plans to move. She still wears his ring, and she still thinks of him as her husband. She sometimes refers to him in the present tense, as if he’s still around. After all these years, she still half expects to see him pop his head around the door. ‘To me it always seems as if Eric’s only just gone,’ she tells me. ‘It never seems to me that it’s been twenty years.’ Yet after today, there will be slightly less of Eric here than there was before. After twenty years, she’s been clearing out her husband’s study – a room that had lain dormant since he died. There was all sorts of stuff in there – photos, letters, joke books, diaries. It sounded as if there might be a book in it. ‘You can’t explain it,’ says Joan. ‘You can’t explain why people still remember him as if he’s still part of their lives.’ She’s probably right. You can never really explain these things – not definitively, not completely. But once I’ve spent a few hours inside Eric’s study, I reckon I’ll have a much better idea.

We go upstairs, past his full length portrait in the stairwell, and into a small room – barely more than a box room, really – where Eric would retreat to read and write. There’s a lovely view out the back, across the golf course and over open fields beyond, where Eric would go golfing or bird watching. He quite liked a round of golf, but on the whole he far preferred birds to birdies. He loved to watch them fly by, especially when he was resting.

However there’s nothing restful about this room, despite its peaceful vistas. This was where Eric came to work, not just to rest or play. ‘This book laden room was his shrine,’ observed Gary, just a few days after his father’s death. ‘Almost every previous time I had entered it, I had discovered his hunched figure poised over his portable typewriter, the whole room engulfed with smoke from his meerschaum pipe.’2 Two decades on, that same sense of restless industry endures. It may be twenty years, but it feels like Eric has just nipped out for an ounce of pipe tobacco. It feels like he’ll be back any minute. It feels as if we’re trespassing in a comedic Tutankhamen’s tomb.

On the floor beside the bookcase is an old biscuit tin. Inside is his passport, his ration book and his Luton Town season ticket. There’s a shoe box full of old pipes, with blackened bowls and well chewed stems. Here’s his hospital tag, made out in his real name, John Bartholomew, so he wouldn’t be pestered by starstruck patients. On the back of the door is his velvet smoking jacket – black and crimson, like a prop from one of Ernie’s dreadful plays. ‘He loved dressing in a Noel Coward kind of way,’ says Gary, vaguely, his thoughts elsewhere. But it’s the books on the shelves above that really catch your eye. Never mind Desert Island Discs. For the uninvited visitor, there’s nothing quite so intimate as someone else’s library. When you scan another person’s bookshelves, it’s as if you’re browsing in the corridors of their mind.

As you might expect, there are stacks of joke books: Laughter, The Best Medicine; The Complete Book of Insults; Twenty Thousand Quips And Quotes. And as you might expect, there are stacks of books about other jokers, many of them American, from silent clowns like Buster Keaton to wise guys like Groucho Marx. Yet it’s the less likely titles that reveal most about Britain’s favourite joker: PG Wodehouse, Richmal Crompton, even the Kama Sutra. And here’s Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers, ‘Eric always told me that The Pickwick Papers was the funniest book he had ever read,’ says Gary. ‘He used to read it on train journeys when he was travelling from theatre to theatre, from digs to digs. He said he’d get strange looks from the people in his carriage, because he was stifling his laughter as he read.’ There’s Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead. There’s a bit of Eric in all these books – well, maybe not the Kama Sutra. Wodehouse? Certainly. Dickens? Of course. Eric and Ernie would have been brilliant as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, but the character Eric most resembles is Crompton’s Just William, an eternal eleven year old with a genius for amiable mischief. ‘Maybe that’s why we loved him as kids,’ says Gary’s lifelong friend, Bill Drysdale, a regular visitor to this house ever since he was a child. ‘The thing that kids love more than anything is the idea of grown ups being naughty. Kids think that’s just the funniest thing, and that’s what I always loved about him.’

Eric wasn’t just a pipe smoker, he was a pipe collector too. He owned several hundred pipes. This one, which he called his Sherlock Holmes pipe, was a particular favourite

Mr and Mrs Eric Morecambe

Ernie: ‘I can see your lips moving. Eric: Well of course you can, you flaming fool! I’m the one who’s doing it for him! He’s made of wood! His mother was a Pole!’ Right to left: Ernie, Eric and Charlie the Dummy, who still resides at the Morecambe residence in Harpenden, awaiting repairs.

As a child, Bill wasn’t remotely awestruck by Eric’s stardom. ‘I never felt alienated by his status,’ he says. ‘You always felt like he was one of us.’ Yet he was full of surprises. After Eric died, Bill found a Frank Zappa album, of all things, in Eric’s record collection. ‘There was often the appearance of anarchy, but there was one person at the centre of things who knew exactly what was going on,’ says Bill, of Zappa’s music, ‘and that is an ideal template, I think, for Eric’s comedy.’ Eric’s comedy wasn’t just a job. It was a way of life. ‘His mind was always working on comedy,’ says Bill. ‘He’d be working in the study, he’d come out and he’d try out a joke on Gary and I, just to see what we thought of it, to see if it was funny.’ He knew if children found it funny, it would be easy to make their parents laugh.

We walk down the narrow corridor, to Eric’s old bedroom. The overflow from his study is strewn across the floor. There’s the giant lollipop which was his trademark before he met Ernie – a twelve year old vaudevillian, kitted out in beret and bootlace tie.3 Here’s a clapperboard from The Intelligence Men, the first feature film he made with Ernie. And there’s the ventriloquist’s dummy that was the highlight of their live show. ‘I can see your lips moving,’ Ernie would protest each time, in immaculate mock indignation. ‘Well of course you flaming can, you fool!’ Eric would answer, furious at this outrageous slur on his professional integrity. ‘I’m the one who’s doing it for him! ‘He’s made of wood! His mother was a Pole!’ ‘He had the common touch,’ says Gary. ‘He wasn’t trying to be hip or clever.’ But that was another part of Eric’s artifice. Eric did what all great artists do. He made it look easy.

There are heaps of photos all around us, some dating back to Eric and Ernie’s first turns together, as teenagers during the war. With his boyish good looks and eager grin, Ernie looks just the same as he always did. Eric, on the other hand, is almost unrecognisable – painfully thin and curiously feminine, with high cheekbones and a full head of dark, wavy hair. There are piles of cuttings too, newspaper after newspaper – countless rave reviews, even the occasional stinker. So important at the time, or so it seemed. All forgotten now, of course. As Eric used to say, to buck himself up after a bad notice, or bring himself back down to earth after a good one, the hardest thing to find is yesterday’s paper. And here they all are – all his daily papers from all his yesteryears. There are endless interviews, in every publication you can think of (and quite a few you can’t) from a profile by Kenneth Tynan in The Observer to a cover story in that classic boy’s comic, Tiger. Today these faded clippings all seem incongruously similar. Highbrow or lowbrow, they’re all mementoes of a life lived almost entirely in the public gaze.

This is a book about the part the public didn’t see. In the wings, in the dressing room, at home or on holiday, Eric Morecambe had a compulsion to amuse. ‘Even if he didn’t have an audience or wasn’t getting paid, he’d still entertain people in his kitchen,’ says Gary. ‘He used to wake up thinking funny. It was almost like an illness.’ Unlike a lot of comics, he didn’t hoard his humour for his paying punters. He was always on.

Some of it ended up on the small screen, where the rest of us could relish it. Some of it vanished into thin air. And the rest is in this room. Here’s his address book – a veritable Who’s Who of the glory days of British showbiz: Ronnie Barker, Roy Castle, Tommy Cooper and Harry Secombe. There’s a number for Des O’Connor, the patient butt of so many put downs, plus sporting pals like Dickie Davies and Jimmy Hill. There are numbers for his writer, Eddie Braben, his producer, John Ammonds, and, naturally, Ernie Wise – plus the British Heart Foundation, an association that ended with his third and final, fatal heart attack, bringing their lifelong partnership to an abrupt and inconclusive end. ‘Eric Morecambe’ reads Eric’s own inscription on the inside cover. ‘Comedian – Retired.’ But Eric never hung up his boots. He worked until the day – the very evening – that he died.

There are other books in this cardboard box, but they’re not address books. They’re notebooks filled with jottings, from diary entries to old jokes. Some, in childlike copperplate, date back half a century. Others, in geriatric scrawl, look like they were scribbled down yesterday. But buried in amongst these reflections, reminiscences and corny old one-liners, two quotations arrest the eye. One is by TS Eliot, from The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock: ‘I grow old, I grow old, I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.’4 The other must be from the Gospel of St. John, which is odd, since Eric wasn’t overtly religious: ‘That which was borne of this flesh is flesh – that which was borne of the spirit is spirit.’ Well, the flesh is gone – long gone – but in those photos and notebooks, and in this book, the daft, endearing spirit of Eric Morecambe lives on. ‘Even when he wasn’t here, it was as if this place was echoing with his infectious laugh,’ says Bill Drysdale. This book is all about the echo of that laughter.

My other car is a Rolls

My other car is a Skoda

Eric and Fiona Castle (Roy Castle’s wife) take each other’s photos

Eric, Joan and their daughter, Gail, along with additional family members Barney, the Retriever, and Chips.

Eric relaxing at Elbow Beach Hotel in Bermuda, on the way home from appearing on the Ed Sullivan Show in New York.

Gail points out her first boyfriend to her father.

Gail and Gary with Eric and Joan in the garden of their home in Harpenden, just after Gail’s confirmation.

Eric with his mother in law, Alice

Eric relaxes by the family pool with wife Joan and children Gail and Gary. In fact, Eric couldn’t swim and never once went in the water.

1969, the day Apollo 11 got back, carved by Eric, with his initials, on a tree in his front garden.

Chez Eric. Left to right: Gail, Joan, Eric and Gary.

A new addition to the family: Joan and Eric’s adopted son, Steven.

Eric and Ernie – tears of a clown.

Chapter 2

MORECAMBE

Eric: I’m not a complete fool.

Ernie: Why? What part’s missing?

‘I’m not saying his ears were big, but when you saw him from the front, he looked like the FA Cup.’ Eric, before his mother Sadie started taping back his ears, to stop them sticking out.

EVEN THE CIRCUMSTANCES of Eric’s birth were vaguely comical. He was born John Eric Bartholomew on 14 May 1926, at 42 Buxton Road, Morecambe, but his mother and father actually lived a few doors away. They’d had to move in with neighbours while their own house was repaired. Once their proper home was patched up they moved back in again, but within a year it had become unfit for human habitation. Eric’s earliest memory was the ceiling collapsing. It must have been pretty awful at the time, of course, especially for his hard pressed parents, but looking back it sounds like a slapstick scene from one of his favourite silent films.

Although he was already taking dancing lessons, and entering local talent contests, Eric’s boyhood dream was to become a professional footballer. And unlike most of his teammates, this was no idle fantasy. A fine left winger, he attracted the interest of several league scouts, but his father, who’d suffered a crippling injury as an amateur, advised him against it. In those days there was no money in it, and your career was over by the time you were thirty, so Eric subsequently decided it would be a better bet to settle for show business instead.

Buxton Road is the sort of terraced street you see in Lowry paintings, full of kids playing football, but by the time Eric was old enough to kick a ball his parents had moved into a new council house, 43 Christie Avenue, behind the main stand of Morecambe Football Club, where Eric lived until he left home. By modern standards, Eric’s childhood home in Christie Avenue looks pretty Spartan, but back in the 1920s it was a proletarian dream come true. It had three bedrooms, its own front door, and best of all, its own garden – still a rarity in those days, especially for folk of the Bartholomew’s humble social standing. This garden was the summit of Eric’s father’s expectations. Luckily for Eric, and the future of British comedy, his mother’s aspirations weren’t confined to this pleasant but unprepossessing patch of lawn.

Eric’s parents both came from similar working class backgrounds, but their personalities could hardly have been less alike. Orphaned at an early age, his mother Sadie was a sharp and restless woman who was always striving to better herself – and her family. His father George, on the other hand, was one of those rare individuals who are utterly contented with their lot. One of life’s plodders, he toiled away serenely as a council labourer from the day he left school until the day he retired, entirely satisfied with the modest cards he’d been dealt. Like the soldier in the wartime song, he really did whistle while he worked. Despite their contrasting attitudes – or perhaps, in part, because of them – George and Sadie got along very well. In their very different ways, they each nurtured Eric, and he formed a close bond with both of them that would sustain him throughout his life. Eric’s incredible career was a testament to his driven (and hard driving) mother, but his happy go lucky stage persona was a tribute to his easy going dad. ‘George was a character,’ says his grandson, Gary. ‘I remember giving him some aftershave for Christmas, and him ringing up and saying it was the worst sherry he’d ever drunk.’ It sounds like a classic Eric Morecambe one liner.

Some of the earliest photos of Eric with his mother, Sadie.

The future Mr Eric Morecambe, OBE.

Lancaster Road Junior School, Morecambe. Eric is second from the left on the front row.

In many ways, Eric’s was a typical working class childhood. His parents were far from affluent (when they went shopping in Lancaster, several miles away, they used to walk home to save the bus fare) but Eric never went hungry. And though money was often pretty tight, he never ran short of fun things to do. On Sundays George would take him fishing, and on Saturdays they’d go to a football match – usually Morecambe, sometimes Blackpool, occasionally mighty Preston North End. Yet there was one aspect of his upbringing that was highly unusual, at least for those days. He was an only child. This oddity was to prove crucial for his future prospects. Had he been one of six children, like his mother, or one of eleven, like his father, it’s highly unlikely he would have been able to pursue the same show business career.

However despite a happy and comparatively comfortable home life, Eric did surprisingly badly at school. ‘I wasn’t just hopeless in class,’ he recalled. ‘I was terrible.’1 His school reports bear him out. Out of a class of 49, he was ranked 45 – and the other four, according to Eric, never even went to school. Eric’s poor academic performance remains a mystery, especially since Sadie was not only intelligent, but diligent too. ‘I am disgusted with this report,’ she wrote to his headmaster, ‘and would be obliged if you would make him do more homework.’ Her efforts were in vain. When Sadie told the head she wanted Eric to go to grammar school, he told her it would be a waste of time. When she said she’d pay for private education, he said it would be money down the drain. For the time being, at least, Eric was his father’s son. ‘I had no bright ambitions,’ he recollected. ‘To me, my future was clear. At fifteen I would get myself a paper round. At seventeen I would learn to read it. And at eighteen I would get a job on the Corporation, like my dad.’2

If there was one thing Eric was good at, it was performing. Ever since he was a toddler, he’d entertained his parents by dancing to the gramophone. Once, he sneaked out of the house and onto a nearby building site, where Sadie found him treating local workmen to a song and dance routine. ‘That little lad’s a wonderful entertainer,’3 said one of them. ‘I’ll entertain him when I get home,’4 said Sadie, yet she did all she could to nurture her son’s nascent talent. Egged on by his mum, Eric studied half a dozen musical instruments, including the piano and the accordion, and although he never mastered any of them, it didn’t do his sense of rhythm any harm. He cultivated his showbiz education at the local cinema, although his interest in the movies came second to his interest in making mischief. On at least one occasion, he was thrown out for firing his pea shooter at the heads of bald men in the stalls.

Sadie also sent Eric to dancing classes, and when the teacher recommended individual lessons, at a cost of two and six a time, she toiled as a charlady to pay for them, on top of her day job as an usherette on Morecambe Central Pier. To make a few extra bob, she’d gather up the discarded programmes, bring them home, iron them until they looked brand new, and resell them at the theatre the next day. Despite her sacrifices, Eric was far from keen. ‘I never liked the lessons,’ he recalled. ‘I’d have much preferred to have spent my time kicking a ball around with my mates.’5 Yet Sadie’s investment soon paid off. Before long, he was playing local working men’s clubs, often for as much as fifteen shillings a time – half his father’s weekly wage.

The Bash Street Kids. Eric is in the middle of the front row. ‘I was just a shy, bashful sort of boy. Why, even when I was six I used to blush every time I hit a policeman.’

Unwillingly to school. A reluctant Eric sets off for Lancaster Road Junior School, where he reached the dizzy heights of 45th out of a class of 49.

As a budding entertainer, Eric was lucky to be the only child of such a shrewd and dedicated mother, but he was also lucky to born in the right place at the right time. Today Morecambe is a quiet resort on the edge of the Lake District, frequented mainly by flocks of wading birds and the birdwatchers that come to watch them, but in the 1930s, when Eric was a lad, it was a thriving holiday town. Smarter than nearby Blackpool, but with much of the same seaside bustle, it was a lively place of entertainment, whose shows spilled out of the dancehalls and onto the promenade. Eric’s mum and dad met at the Winter Gardens, a splendid ballroom where Eric would later perform with Ernie. Full of precocious self confidence, he entered talent contests on the prom, winning so often that locals were eventually barred from competing, since his success was discouraging genuine holidaymakers from joining in.

Eric’s dad Georgs (far right) with his workmates from Morecambe Corporation. A world away from the Morecambe & Wise Show.

Fortunately, such competitions weren’t confined to Morecambe promenade, and Sadie soon found a bigger stage for her prodigious child. After several decent write ups in the local press, he finally got his big break in 1939 when he won a juvenile talent show in Hoylake, a seaside town on the Wirral. For Eric, it felt like travelling to Australia, but this odyssey was well worthwhile. ‘Eric Bartholomew put over a brilliant comedy act which caused the audience to roar with laughter,’ reported the Melody Maker, the show’s sponsor, and their interview with Eric revealed another side to the lad who’d been content to drift through school. ‘My ambition is to be a comedian,’ Eric told the paper. ‘My hero is George Formby.’ In later life, Eric confessed that he actually found Formby ‘about as funny as a cry for help,’6 but it was telling that his role model was one of the best known (and best paid) comics in the country. His dad’s laid back approach, which informed Eric’s lackadaisical school career, had been eclipsed by his mum’s determination and drive.

Eric’s mum and dad, George and Sadie (right), all set to emigrate to America, with George’s brother, Jack, and Jack’s wife, Alice, They’d even bought their tickets, but then Jack fell ill, and they all got cold feet. Just think: if Jack hadn’t been poorly, Eric would have grown up in America. Would he have become the next Bob Hope? Or merely the next John Bartholomew?

Eric with his mum and dad, George and Sadie, in their Sunday best.

Eric’s prize was yet another audition, but this try out was a cut above the usual talent show. This time, he’d won an audience with Jack Hylton, one of the top impresarios in the land. The audition was held in Manchester, another epic journey for Eric. Sadie couldn’t stand those showbiz mums who sought glory through the (real or imagined) talents of their children. Nevertheless, she was determined to get Eric’s head out of the clouds and – if at all possible – improve his prospects. Hence, she left him in no doubt about the significance of this trip. ‘She drummed into me all the way from Morecambe that this just might be the most important day of my life,’ recalled Eric. ‘And she was right.’7 For sitting in the stalls, in pride of place alongside Hylton, was an accomplished young entertainer called Ernie Wise.

Eric in his talent contest days.

A dapper, dashing young Eric poses for his public alongside a female admirer (his Auntie Alice).

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.