Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

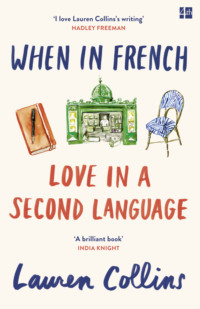

Buch lesen: "When in French: Love in a Second Language"

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2016

First published in the US by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC in 2016

Copyright © Lauren Collins 2016

Cover illustration © Jessie Kanelos Weiner

Lettering © Christopher Brian King

The right of Lauren Collins to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Excerpt from ‘FOR ME … FOR-MI-DA-BLE’ by Charles Aznavour, Jacques Plante,

Gene Lees © 1963 & 1974 Editions Charles Aznavour, Paris, France

assigned to TRO Essex Music Ltd of Suite 2.07,

Plaza 535, King’s Road, London, SW10 0SZ

International Copyright Secured.

All rights reserved. Used by Permission.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008100629

Ebook Edition © September 2016 ISBN: 9780008100605

Version: 2017-06-28

Dedication

For Olivier

Epigraph

You are the one for me, for me, for me, formidable

But how can you

See me, see me, see me, si minable

Je ferais mieux d’aller choisir mon vocabulaire

Pour te plaire

Dans la langue de Molière

—Charles Aznavour, “For Me, For-mi-da-ble”

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

One: THE PAST PERFECT – Le Plus-que-parfait

Two: THE IMPERFECT – L’Imparfait

Three: THE PAST – Le Passé composé

Four: THE PRESENT – Le Présent

Five: THE CONDITIONAL – Le Conditionnel

Six: THE SUBJUNCTIVE – Le Subjonctif

Seven: THE FUTURE – Le Futur

Acknowledgments

About the Publisher

One

THE PAST PERFECT

Le Plus-que-parfait

I HADN’T WANTED to live in Geneva. In fact, I had decisively wished not to, but there I was. Plastic ficuses flanked the entryway of the building. The corrugated brown carpet matched the matte brown fretwork of the elevator cage. The ground floor hosted the offices of a psychiatrist and those of an iridologue—a practitioner of a branch of alternative medicine that was popularized when, in 1861, a Hungarian physician noticed similar streaks of color in the eyeballs of a broken-legged man and a broken-legged owl. Our apartment was one story up.

The bell rang. Newlywed and nearly speechless, I cracked open the door, a slab of oak with a beveled brass knob. Next to it, the landlord had installed a nameplate, giving the place the look less of a home than of a bilingual tax firm.

A man stood on the landing. He was dressed in black—T-shirt, pants, tool belt. A length of cord coiled around his left shoulder. In his right hand, he held a brush. Creosote darkened his face and arms, extending his sleeves to his fingernails and the underside of his palms. A red bandanna was tied around his neck. He actually wore a top hat. I hesitated before pushing the door open further, unsure whether I was up against a chimney sweep or some sort of Swiss strip-o-gram.

“Bonjour,” I said, exhausting approximately half of my French vocabulary.

The man, remaining clothed, returned my greeting and began to explain why he was there. His words, though I couldn’t understand them, jogged secondhand snatches of dialogue: per cantonal law, as the landlord had explained to my husband, who had transmitted the command to me, we had to have our fireplace cleaned once a year.

I led the chimney sweep to the living room. It was dominated by the fireplace, an antique thing in dark striated marble, with pot hooks and a pair of side ducts whose covers hinged open like lockets. Shifting his weight onto one leg with surprising grace, the chimney sweep leaned forward and stuck his head under the mantel. He poked around for a few minutes, letting out the occasional wheeze. Coming out of the arabesque, he turned to me and began, again, to speak.

On a musical level, whatever he was saying sounded cheerful, a scale-skittering ditty of les and las. Perhaps he was admiring the condition of the damper, or welcoming me to the neighborhood. He reached into his pocket, proffering a matchbook and a disc of cork. Then he disappeared.

Minutes went by as I examined his gifts. They seemed like props for a magic trick. More minutes passed. I launched into a version of rock, scissors, paper: since the cork couldn’t conceivably do anything to the matches, then the matches must be meant to light the cork. Action was required, but I feared potentially incinerating the chimney sweep, who, I guessed, was making some sort of inspection up on the roof.

Eventually he returned, chirping out some more instructions. I performed a repertoire of reassuring eyebrow raises and comprehending head nods. He scampered away. I still had no idea, so I lit a match, held it to the cork, and tossed it behind the grate. The pile started smoking and hissing. After a few seconds, I lost my nerve and snuffed it out.

The chimney sweep resurfaced, less jolly. He had appointed an assistant who, it appeared, was actively thwarting his routine. This time he spoke in the supple, obvious tones one reserves for madwomen, especially those in possession of flammable objects. Reclaiming the half-charred piece of cork, he lit a fire and, potbelly jiggling, sprinted back out the door.

Finally, he returned and reported—I assume, since we used the fireplace without incident all that winter—that everything was in order.

“Au revoir!” I said, trying to regain his confidence, and my standing as chatelaine of this strange, drab domain. “Hello” and “good-bye” were a pair of bookends, propping up a vast library of blank volumes, void almanacs, novels full of sentiment I couldn’t apprehend. It felt as though the instruction manual to living in Switzerland had been written in invisible ink.

I HAD MOVED to Geneva a month earlier to be with my husband, Olivier, who had moved there because his job required him to. My restaurant French was just passable. Drugstore French was a stretch. IKEA French was pretty much out of the question, meaning that, since Olivier, a native speaker, worked twice as many hours a week as Swiss stores were open, we went for months without things like lamps.

He had already been living in Geneva for a year and a half. Meanwhile, I had remained in London, where we’d met. The commute was tolerable, then tiring. In the spring of 2013, as our wedding approached, it was becoming a drag. Finally, that June, a visa fiasco abruptly forced me to leave England. Memoirs of immigration, like memories of immigration, often begin with a sense of approach—the ship sailing into the harbor, the blurred countryside through the windows of a train. My arrival in Geneva, on British Airways, was a perfect anticlimax, the modern ache of displacement anesthetized amid blank corridors of orange liqueur and fountain pens.

When Lord Byron arrived in Switzerland for an extended holiday in May 1816—fleeing creditors, gossips, and his wife, from whom he had recently separated, after likely fathering a child with his half sister—his entourage included a valet, a footman, a personal physician, a monkey, and a peacock. That summer he wrote The Prisoner of Chillon, the tale of a sixteenth-century Genevan monk, most of whose family has been killed in battle or burned at the stake. “There were no stars, no earth, no time / No check, no change, no good, no crime,” the poem reads. As a description of the local atmosphere, that seemed to me about right. Geneva was unlovely, but not hideous, as though no one had cared enough to do ugly with conviction. The city seemed suffused by complacency, as gray and costive as the clouds that hovered over Lac Léman.

The main attraction was a clock made of begonias. Transportation was by tram. At the Office Cantonal de la Population, I was given a “Practical Guide to Living in Geneva,” ostensibly a welcome booklet. “It is forbidden and not well looked upon to make too much noise in your apartment between 21:00 and 07:00,” it read. “Also avoid talking too loudly, and shouting to call someone in public places.” The booklet directed me to a web page, which listed further gradations of bruit admissible (acceptable noise) and bruit excessif (excessive noise). Vacuuming during the day was okay, but God help the voluptuary who ran the washing machine after work.

Geneva had long been a place of asylum, but its tradition of liberty in the religious and political realms had never given rise to a libertine scene. Even though nearly half of the population was foreign-born, the city remained resolutely uncosmopolitan, a tepid fondue of tearooms, confectionaries, and storefronts selling things like hosiery and lutes. Every block had its coiffeur, just as every coiffeur had its lone patroness, getting her hair washed in the sink. It wasn’t as though Genevans enjoyed the advantages of living in the countryside. Many of them, native and nouveau, had means. So why hadn’t some son or daughter of the city, after traveling to New York or Paris or Beirut—to Dallas or Manchester—been inspired to open a place where the bread didn’t come in a doily-lined wicker basket? Was there a dinkier phrase, in any language, than métropole lémanique?

After a month or so of heavy tramming, we decided to buy a car. We purchased insurance, which included coverage for theft, fire, natural disasters, and dommages causés par les fouines—damages caused by a type of local weasel. I traded in my American driver’s license for a Swiss one. The process took seventeen minutes flat. One sodden afternoon not long after, we trammed over to the Citroën lot.

Alexandre, a customer service representative, greeted us. He smelled of cigarettes and was wearing a tie.

“So, voici,” he said. (Switzerland has four official languages—German, French, Italian, and Romansh—and people tended to switch back and forth without warning, with varying degrees of success.) He led us to the car, a used hatchback parked outside the office on a covered ramp.

It was pouring, each drop of rain a suicide jumper, hurling itself onto the ramp’s tin roof. We circled the car, hoping to project a discerning vibe, as though any painted-over weasel damage would never get by us.

Olivier stopped on the car’s left side and, because it seemed like the thing to do, opened the backseat door.

“You will soon have des petits enfants?” Alexandre said.

“Um, we just got married.”

“Ah, bon? It was a Protestant or a Catholic ceremony?”

Our city hall wedding was an unimaginability for Alexandre. I was beginning to understand, only very slowly, that the city’s conservatism was neither an accident of demographics nor an oversight but an enactment of its founding values by conscious design. In 1387, more than a hundred years before the Catholic Church began to loosen its prohibitions on usury, the bishop of Geneva signed a charter of liberties, granting the genevois, alone in Christendom, the privilege of lending money at interest. The elite became financiers. The aspirant became Swiss mercenaries. Famed for their ferocity with the halberd and the pike, they poured cash into the economy in an era when most of the world’s population was getting paid in eggs.

The mentality had persisted: do your hell-raising—your eating in restaurants without doilies—abroad, and retreat to a place of imperturbable security. Voltaire wrote of Geneva, “There, one calculates, and never laughs.” Stendhal, passing through seventy years later, concluded that the genevois, despite their wealth and worldly networks, were at heart a parochial people: “Their sweetest pleasure, when they are young, is to dream that one day they will be rich. Even when they indulge in some imprudence and abandon themselves to pleasure, the ones they choose are rustic and cheap: a walk, to the summit of some mountain where they drink milk.” Monotony, then, was an economy. So that we could collectively accrue more capital, a curfew had been set.

Weekends were the worst. All of the shops closed at seven—except on Thursdays, when some of them closed at seven thirty—rendering Saturdays a dull frenzy of provisioning. Sundays were desolate, a relic of the Calvinist lockdown mentality that had sent the young Rousseau scrambling to Savoy. A relocation consultant furnished by Olivier’s company said that there had been talk of easing the Sunday moratorium, but to no avail. “Approximately ninety-nine percent of Swiss people support it,” he said, sounding to us approximately one hundred percent like a Swiss person.

Geneva had its graces—the trams operated on an honor system; even the graffiti artists were mannerly, defacing the sides of statues that didn’t face the street—but I took them as further proof that the city was second-rate. You could, of course, escape to any number of attractive places within driving range, and we passed many afternoons wandering the relatively bustling streets of Lyon. It seemed sad, though, that the main selling point of the place where we lived was its proximity to places where we’d rather live. And while the mountains that surrounded us were magnificent, the twenty-five or so times a year that we managed to take advantage of them didn’t make up for the three hundred and forty times we didn’t. On Sunday nights, after an outing, we’d return to our stockpiled supper and take out the recycling, casting bottles and cans into the maw of a public bin. This was our version of indulging in an imprudence: you could get fined for recycling—for recycling, I had not missed a negative adverb—on the day of rest.

Behind its orderly facade—the apartment buildings with their sauerkraut paint jobs; the matrons in furs; the brutalist plazas; the allées of pollarded trees—Geneva was, if anything, faintly sinister. Its vaunted sense of discretion seemed a cover for dodginess, bourgeois respectability masking a sleazy milieu. What was going on in those clinics and cabinets? Whose money, obtained by what means, was stashed in the private banks? What was a “family office,” anyway?

One day I received an e-mail from the Intercontinental Hotel Genève, entitled “What You Didn’t Know about Geneva.” I did not know that the Intercontinental Hotel Genève “continues to cater to the likes of the Saudi Royal family and the ruling family of the United Arab Emirates,” that the most expensive bottle of wine sold at auction was sold in Geneva (1947 Château Cheval Blanc, $304,375), that the most expensive diamond in the world was sold in Geneva (the Pink Star, a 59.6-carat oval-cut pink diamond, $83 million), or that Geneva “has witnessed numerous world records, such as the world’s longest candy cane, measuring 51 feet long.” I developed a theory I thought of as the Édouard Stern principle, after the French investment banker who was found dead in a penthouse apartment in Geneva—shot four times, wearing a flesh-colored latex catsuit, trussed. Read any truly tawdry news story, and Geneva will somehow play into it by the fifth paragraph. Balzac wrote that behind every great fortune lies a crime. In Switzerland, behind every crime seemed to lie a great fortune.

Around us Europe was reeling, but the stability of the Swiss franc, combined with the influx of people who sought to exploit it, made the city profoundly expensive. The stores were full of things we neither wanted nor could afford. I reacted by refusing to buy or do anything that I thought cost too much money, which was pretty much everything, and then complaining about my boredom. Geneva syndrome: becoming as tedious as your captor. The expanses of my calendar stretched as pristine as those of the Alps.

Olivier didn’t love Geneva either, but he didn’t experience it as an effacement. He said that it reminded him of a provincial French town in the 1980s—a setting and an epoch with which he was well acquainted, having grown up an hour outside Bordeaux during the Mitterrand years. His consolations were familiarities: reciting the call-and-response of francophone pleasantries with the women at the dry cleaners; reading Le Canard enchaîné, the French satirical newspaper, when it came out each Wednesday; watching the TV shows—many of them seemed to involve puppets—that he knew from home. He was living in a sitcom, with a laugh track and wacky neighbors. I was stranded in a silent film.

WE HAD ESTABLISHED our life together, in London, on more or less neutral ground: his continent, my language. It worked. Olivier was my guide to living outside of the behemoth of American culture; I was his guide to living inside the behemoth of English.

He had learned the language over the course of many years. When he was sixteen, his parents sent him to Saugerties, New York, for six weeks: a homestay with some acquaintances of an English teacher in Bordeaux, the only American they knew. Olivier landed at JFK, where a taxi picked him up. This was around the time of the Atlanta Olympic Games.

“What is the English for ‘female athlete’?” he asked, wanting to be able to discuss current events.

“ ‘Bitch,’” the driver said.

They drove on toward Ulster County, Olivier straining for a glimpse of the famed Manhattan skyline. The patriarch of the host family was an arborist named Vern. Olivier remembers driving around Saugerties with Charlene, Vern’s wife, and a friend of hers, who begged him over and over again to say “hamburger.” He was mystified by the fact that Charlene called Vern “the Incredible Hunk.”

Five years later Olivier found himself in England, a graduate student in mathematics. Unfortunately, his scholastic English—“Kevin is a blue-eyed boy” had been billed as a canonical phrase—had done little to prepare him for the realities of the language on the ground. “You’ve really improved,” his roommate told him, six weeks into the term. “When you got here, you couldn’t speak a word.” At that point, Olivier had been studying English for more than a decade.

After England, he moved to California to study for a PhD, still barely able to cobble together a sentence. His debut as a teaching assistant for a freshman course in calculus was greeted by a mass defection. On the plus side, one day he looked out upon the residue of the crowd and noticed an attentive female student. She was wearing a T-shirt that read “Bonjour, Paris!”

By the time we met, Olivier had become not only a proficient English speaker but a sensitive, agile one. Upon arriving in London in 2007, he’d had to take an English test to obtain his license as an amateur pilot. The examiner rated him “Expert”: “Able to speak at length with a natural, effortless flow. Varies speech flow for stylistic effect, e.g. to emphasize a point. Uses appropriate discourse markers and connectors spontaneously.” He was funny, quick, and colloquial. He wrote things like (before our third date), “Trying to think of an alternative to the bar-restaurant diptych, but maybe that’s too ambitious.” He said things like (riffing on a line from Zoolander as he pulled the car up, once again, to the right-hand curb), “I’m not an ambi-parker.” I rarely gave any thought to the fact that English wasn’t his native tongue.

One day, at the movies, he approached the concession stand, taking out his wallet.

“A medium popcorn, a Sprite, and a Pepsi, please.”

“Wait a second,” I said. “Did you just specifically order a Pepsi?”

In a word, Olivier had been outed. Due to a traumatic experience at a drive-through in California, he confessed, he still didn’t permit himself to pronounce the word “Coke” aloud. For me, it was a shocking discovery, akin to finding out that a peacock couldn’t really fly. I felt extreme tenderness toward his vulnerability, mingled with wonderment at his ingenuity. I’d had no idea that he still, very occasionally, approached English in a defensive posture, feinting and dodging as he strutted along.

I only knew Olivier in his third language—he also spoke Spanish, the native language of his maternal grandparents, who had fled over the Pyrenees during the Spanish Civil War—but his powers of expression were one of the things that made me fall in love with him. For all his rationality, he had a romantic streak, an attunement to the currents of feeling that run beneath the surface of words. Once he wrote me a letter—an inducement to what we might someday have together—in which every sentence began with “Maybe.” Maybe he’d make me an omelet, he said, every day of my life.

We moved in together before long. One night, we were watching a movie. I spilled a glass of water, and went to mop it up with some paper towels.

“They don’t have very good capillarity,” Olivier said.

“Huh?” I replied, continuing to dab at the puddle.

“Their capillarity isn’t very good.”

“What are you talking about? That’s not even a word.”

Olivier said nothing. A few days later, I noticed a piece of paper lying in the printer tray. It was a page from the Merriam-Webster online dictionary:

capillarity noun

1: the property or state of being capillary

2: the action by which the surface of a liquid where it is in contact with a solid (as in a capillary tube) is elevated or depressed depending on the relative attraction of the molecules of the liquid for each other and for those of the solid

Ink to a nib, my heart surged.

There was eloquence, too, in the way he expressed himself physically—a perfect grammar of balanced steps and filled glasses and fingertips on the back of my elbow, predicated on some quiet confidence that we were always already a compound subject. The first time we said good-bye, he put his hands around my waist and lifted me just half an inch off the ground: a kiss in commas. I was short; he was not much taller. We could look each other in the eye.

But despite the absence of any technical barrier to comprehension, we often had, in some weirdly basic sense, a hard time understanding each other. The critic George Steiner defined intimacy as “confident, quasi-immediate translation,” a state of increasingly one-to-one correspondence in which “the external vulgate and the private mass of language grow more and more concordant.” Translation, he explained, occurs both across and inside languages. You are performing a feat of interpretation anytime you attempt to communicate with someone who is not like you.

In addition to being French and American, Olivier and I were translating, to varying degrees, across a host of Steiner’s categories: scientist/artist, atheist/believer, man/woman. It seemed sometimes as if generation was one of the few gaps across which we weren’t attempting to stretch ourselves. I had been conditioned to believe in the importance of directness and sincerity, but Olivier valued a more disciplined self-presentation. If, to me, the definition of intimacy was letting it all hang out, to him that constituted a form of thoughtlessness. In the same way that Olivier liked it when I wore lipstick, or perfume—American men, in my experience, often claimed to prefer a more “natural” look—he trusted in a sort of emotional maquillage, in which people took a few minutes to compose their thoughts, rather than walking around, undone, in the affective equivalent of sweatpants. For him, the success of le couple—a relationship, in French, was something you were, not something you were in—depended on restraint rather than uninhibitedness. Where I saw artifice, he saw artfulness.

Every couple struggles, to one extent or another, to communicate, but our differences, concealing each other like nesting dolls, inhibited our trust in each other in ways that we scarcely understood. Olivier was careful of what he said to the point of parsimony; I spent my words like an oligarch with a terminal disease. My memory was all moods and tones, while he had a transcriptionist’s recall for the details of our exchanges. Our household spats degenerated into linguistic warfare.

“I’ll clean the kitchen after I finish my dinner,” I’d say. “First, I’m going to read my book.”

“My dinner,” he’d reply, in a babyish voice. “My book.”

To him, the tendency of English speakers to use the possessive pronoun where none was strictly necessary sounded immature, stroppy even: my dinner, my book, my toy.

“Whatever, it’s my language,” I’d reply.

And why, he’d want to know later, had I said I’d clean the kitchen, when I’d only tidied it up? I’d reply that no native speaker—by which I meant no normal person—would ever make that distinction, feeling as though I were living with Andy Kaufman’s Foreign Man. His literalism missed the point, in a way that was as maddening as it was easily mocked.

For better or for worse, there was something off about us, in the way that we homed in on each other’s sentences, focusing too intently, as though we were listening to the radio with the volume down a notch too low. “You don’t seem like a married couple,” someone said, minutes after meeting us at a party. We fascinated each other and frustrated each other. We could go exhilaratingly fast, or excruciatingly slow, but we often had trouble finding a reliable intermediate setting, a conversational cruise control. We didn’t possess that easy shorthand, encoding all manner of attitudes and assumptions, by which some people seem able, nearly telepathically, to make themselves mutually known.

IN GENEVA, my lack of French introduced an asymmetry. I needed Olivier to execute a task as basic as buying a train ticket. He was my translator, my navigator, my amanuensis, my taxi dispatcher, my schoolmaster, my patron, my critic. Like someone very young or very old, I was forced to depend on him almost completely. A few weeks after the chimney sweep’s visit, the cable guy came: I dialed Olivier’s number and surrendered the phone, quiescent as a traveler handing over his papers. I had always been the kind of person who bounded up to the maître d’ at a restaurant, ready to wrangle for a table. Now, I hung back. I overpaid and underasked—a tax on inarticulacy. I kept telling waiters that I was dead—je suis finie—when I meant to say that I had finished my salad.

I was lucky, I knew, privileged to be living in safety and comfort. Materially, my papers were in order. We had received a livret de famille from the French government, attesting that I was a member of the family of a European citizen. (The book, a sort of secular family bible, charged us to “assure together the moral and material direction of the family,” and had space for the addition of twelve children.) My Swiss residency permit explained that I was entitled to reside in the country, with Olivier as my sponsor, under the auspices of “regroupement familial.”

Emotionally, though, I was a displaced person. In leaving America and, then, leaving English, I had become a double immigrant or expatriate or whatever I was. (The distinctions could seem vain—what was an “expat” but an immigrant who drinks at lunch?) I could go back, but I couldn’t: Olivier had lived in the United States for seven years and was unwilling to repeat the experience, fearing he would never thrive in a professional culture dominated by extra-large men discussing college sports. Some of my friends were taken aback that a return to the States wasn’t up for discussion, but I felt I didn’t have much choice. I wasn’t going to dragoon Olivier into an existence that he had tried, and disliked, and explicitly wanted to avoid. Besides, I enjoyed living in Europe. For me, the first move, the physical one, had been easy. The transition into another language, however, was proving unexpectedly wrenching. Even though I had been living abroad—happily; ecstatically, even—for three years, I felt newly untethered in Geneva, a ghost ship set sail from the shores of my mother tongue.

My state of mindlessness manifested itself in bizarre ways. I couldn’t name the president of the country I lived in; I didn’t know how to dial whatever the Swiss version was of 911. When I noticed that the grass medians in our neighborhood had grown shaggy with neglect, I momentarily thought, “I should call the city council,” and then abandoned the thought: it seemed like scolding someone else’s kids. Because I never checked the weather, I was often shivering or soaked. Every so often I would walk out the door and notice that the shops were shuttered and no one was wearing a suit. Olivier called these “pop-up holidays”—Swiss observances of which we’d failed to get wind. Happy Saint Berthold’s Day!

In Michel Butor’s 1956 novel Passing Time, a French clerk is transferred to the fictitious English city of Bleston-on-Slee, a hellscape of fog and furnaces. “I had to struggle increasingly against the impression that all my efforts were foredoomed to failure, that I was going round and round a blank wall, that the doors were sham doors and the people dummies, the whole thing a hoax,” the narrator says. Geneva felt similarly surreal. The city seemed a diorama, a failure of scale. Time unfurled vertically, as though, rather than moving through it, I was sinking down into it, like quicksand. I kept having a twinge in the upper right corner of my chest. It felt as though someone had pulled the cover too tight over a bed.

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.