Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Kingdom of Olives and Ash: Writers Confront the Occupation"

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

Compilation and introduction copyright © 2017 by Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman

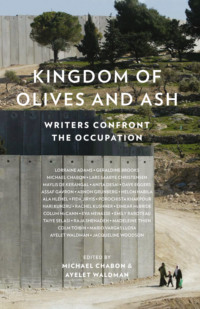

Cover photograph by Uriel Sinai © Photonica world/Getty Images

The names and identifying characteristics of a number of individuals depicted in this book have been changed

Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman assert the moral right to be identified as the editors of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008229191

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008229207

Version: 2017-05-08

Contents

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

INTRODUCTION: AYELET WALDMAN AND MICHAEL CHABON

THE DOVEKEEPER: GERALDINE BROOKS

ONE’S OWN PEOPLE: JACQUELINE WOODSON

BLOATED TIME AND THE DEATH OF MEANING: ALA HLEHEL

GIANT IN A CAGE: MICHAEL CHABON

THE LAND IN WINTER: MADELEINE THIEN

MR. NICE GUY: RACHEL KUSHNER

SAMI: RAJA SHEHADEH

OCCUPIED WORDS: LARS SAABYE CHRISTENSEN

PRISON VISIT: DAVE EGGERS

SUMUD: EMILY RABOTEAU

JOURNEY TO THE WEST BANK: MARIO VARGAS LLOSA

PLAYING FOR PALESTINE: ASSAF GAVRON

LOVE IN THE TIME OF QALANDIYA: TAIYE SELASI

IMAGINING JERICHO: COLM TÓIBÍN

THE END OF REASONS: EIMEAR MCBRIDE

HIGH PLACES: HARI KUNZRU

STORYLAND: LORRAINE ADAMS

THE SEPARATION WALL: HELON HABILA

A HUNDRED CHILDREN: EVA MENASSE

VISIBLE, INVISIBLE: TWO WORLDS: ANITA DESAI

HIP-HOP IS NOT DEAD: POROCHISTA KHAKPOUR

OCCUPATION’S UNTOLD STORY: FIDA JIRYIS

AN UNSUITABLE PLACE FOR CLOWNS: ARNON GRUNBERG

JUSTICE, JUSTICE YOU SHALL PURSUE: AYELET WALDMAN

TWO STORIES, SO MANY STORIES: COLUM MCCANN

H2: MAYLIS DE KERANGAL

AFTERWORD

FOOTNOTES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CONTRIBUTORS

PERMISSIONS

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

INTRODUCTION

AYELET WALDMAN AND MICHAEL CHABON

WE DIDN’T WANT TO EDIT THIS BOOK. WE DIDN’T WANT TO write or even think, in any kind of sustained way, about Israel and Palestine, about the nature and meaning of occupation, about intifadas and settlements, about whose claims were more valid, whose suffering more bitter, whose crimes more egregious, whose outrage more justified. Our reluctance to engage with the issue was so acute that for nearly a quarter of a century we didn’t even visit the place where Ayelet was born.

We had gone to Israel in 1992, a few months after we met. Though raised primarily in the United States and Canada, Ayelet had been born in Jerusalem, the daughter of immigrants from Montreal, and had lived and studied in Israel on and off over the years; it was Michael’s first time. The Oslo accords were fresh and untested; it was a time of optimism, new initiatives, relative tranquility. We visited family and friends, made the requisite tourist pilgrimages to Yad Vashem, the Western Wall, Masada, the Dead Sea. We also spent time in the Muslim quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem, and visited celebrated mosques there, including the al-Aqsa, and in Akko. Some of what Michael saw during that time found its way, after undergoing a sea change, into the pages of The Yiddish Policemen’s Union. It was a memorable visit, the first, we imagined, of many we would be making together.

We didn’t go back for twenty-two years.

Over the course of that period, the tentative hope that followed Oslo vanished. Yitzhak Rabin was murdered. A second intifada, long and bloody, arose and was violently put down. The pace and extent of settlement construction in the territories increased, and the military occupation grew more entrenched, more brutal, more immiserating. Horrified and bewildered by the blur of violence and destruction, of reprisal and counter-reprisal and counter-counter-reprisal, put off by the dehumanizing rhetoric prevalent on both sides, we did what so many others in the ambivalent middle have done: we averted our gaze. We opted out of the debate, and stayed away from the country.

But in 2014, at the invitation of the Jerusalem International Writers’ Festival, Ayelet went back to Israel. While she was there, she met with some of the courageous members of Breaking the Silence (BTS), a nonprofit organization composed of former Israeli soldiers whose service in the occupied territories has inexorably led them to work vigorously and courageously to oppose the occupation and bring it to an end. BTS took Ayelet on a tour of the city of Hebron. They introduced her to Issa Amro, the founder of a grassroots group called Youth Against Settlements, whose nonviolent actions and campaigns are among the most prominent and creative in the West Bank. For the first time she had a clear, visceral understanding of just what occupation meant, of how it operated, and of the decades of Israeli strategic planning that had gone into creating the massive, often brutal, always dehumanizing military bureaucracy that oversees and controls it.

Then Ayelet went to Tel Aviv and spent some time in the company of writers, filmmakers, artists, and intellectuals who live in that cosmopolitan city, where gay couples walk hand in hand in the streets, where chic restaurants put their own creative spin on traditional Middle Eastern cuisine, and where the pace and tenor of life is sababa (an Israeli slang term, of Arabic origin, whose meaning is akin to the American slang term “chill”). The city sparkles; it hums. And it averts its gaze. One would never know, on the streets of Tel Aviv, that an hour’s drive away, millions of people are living and dying under oppressive military rule.

Ayelet had a wonderful time in Tel Aviv, and therein lay the problem. She felt so at ease in the country of her birth, so at home. But if she felt that way—that somehow she belonged to this country, by virtue of birth and temperament and upbringing, by virtue of being Jewish—then so too did she bear some measure of responsibility for the crimes and injustices perpetrated in the name of that home and its “security.”

Once Ayelet had come to that conclusion, however, she was immediately confronted with a new problem: she felt powerless. How could she do anything to effect meaningful change, no matter how small, in this intractable morass that had defeated the best and worst efforts of dozens of presidents and prime ministers, secretaries of state, Nobel Prize winners and NGOs, statesmen and diplomats and peace activists, not to mention generations of violent extremists of every stripe who had sought their own twisted solutions?

When Ayelet came home from that trip she told Michael what she had seen in Hebron. She described the steel bars that had been welded across townspeople’s front doors, sealing them in their homes. She related the frightening moment when a couple of young Palestinian boys had dared to set foot on the main street of their own city, a street on which Palestinians are barred from walking, putting themselves at risk and at the mercy of heavily armed IDF troops, out of some combination of boredom, bravado, and desperation. She described how disgusted she had been by graffiti scrawled on walls across Palestinian Hebron calling, in Hebrew, for the death of Arabs. She told him the story of the things she had seen and heard, and as Michael listened, his reluctance, the product of decades of disenchantment and disengagement, began to fade.

As it faded we both began to realize that storytelling itself—bearing witness, in vivid and clear language, to things personally seen and incidents encountered—has the power to engage the attention of people who, like us, have long since given up paying attention, or have simply given up.

Storytelling—that was a territory, free and unrestricted, that we knew well. More important, we knew a lot of storytellers: creative writers and novelists whose entire job consists, according to Henry James, of being “one on whom nothing is lost.” Professional payers of attention, they had the skill and the talent, if we could engage them, to engage others, using their mastery of language and eye for telling detail to encourage people to stop averting their gazes, to take another look, and maybe see something that fifty years of news reports, white papers, and propaganda had missed.

So, conscious of the imminence of June 2017, the fiftieth anniversary of the occupation, we put the word out—to writers on every continent except Antarctica, of all ages and eight mother tongues. Writers who identified as Christian, Muslim, Jewish, and Hindu, and writers of no religious affiliation at all. Some had already made clear and public their political feelings on the subject of Palestine-Israel, but most had not, and many acknowledged from the outset that they had never really given the subject more than a glancing consideration. For many it was their first visit to the area; some were returning to a place they knew well. The Palestinian and Israeli writers were writing about home. They all came away, as we’d only dared to hope, brimming over with the vividness of the things they had seen, and the need to put it into words, to share the story.

Over the course of 2016, the writers in this volume, in small parties that ranged from a single person to as many as seven individuals, came to Palestine-Israel, on delegations organized by Breaking the Silence. Once there, they spent most of their time in the occupied territories, in East Jerusalem neighborhoods like Silwan, Sheikh Jarrah, and the Shuafat refugee camp; in West Bank cities like Hebron, Ramallah, Nablus, Jericho, and Bethlehem; in West Bank villages including Nabi Saleh, Susiya, Bili’in, Umm al-Khair, Jinba, al-Wallajeh, Kufr Qaddum; and in the Gaza Strip. In these places, the writers met with Palestinian community organizers and nonviolent protest leaders, among them Issa Amro, as well as with shop owners, artists, intellectuals, and laborers, women’s rights advocates and journalists, businesspeople and farmers, grandparents, parents, and children. They also met with Israeli settlers and with Israeli and Palestinian antioccupation activists, human rights lawyers, academics, and writers. In each case, the individual inclination and interest of the writer drove his or her itinerary—some slept over at families’ houses in Palestinian refugee camps, villages, and cities, while others explored soap factories and archeological sites. Some visited the military court, others spent time with bereaved Palestinian and Israeli families. The subjects chosen by the authors were diverse and varied; this breadth of experience, perspective, and narrative is reflected in the pages of this book.

We want to be clear: we had no political expectations of these writers. We invited them to participate in this project based on their literary excellence and their influence over wide and devoted readerships in their own countries and in many cases all around the world. We did not censor them or try to restrict their words in any way. What they saw is what they wrote is what you’ll read. A team of scrupulous fact-checkers labored for months to confirm the veracity and factual basis of each of these essays.

Finally, as with all the other writers involved in this project, neither of us has or will ever receive payment of any kind for our work. All royalties from the sales of Kingdom of Olives and Ash, after expenses, will be divided between Breaking the Silence and Youth Against Settlements, whose hard, unremunerated, twilit work will go on long, long after the reader has turned the last page.

THE DOVEKEEPER

GERALDINE BROOKS

THEIR PLANS WERE QUITE PRECISE: THEY WOULDN’T ATTACK WOMEN, or the elderly, or children like themselves. Their targets, they agreed, would be men in their late teens and early twenties—young men of military age. All this was settled between them before they left the house.

Hassan Manasra, fifteen, took a carving knife from his mother’s kitchen, but his cousin Ahmed, thirteen, couldn’t find the long, daggerlike knife he’d intended to use for his weapon. It took him a while, but finally he located it, concealed in a cupboard, where his father had hidden it for safekeeping.

The Manasras live in a compound of multifamily homes occupying almost a block in the Jerusalem hillside neighborhood of Beit Hanina. In the shared courtyard, half a dozen bicycles of various sizes are propped against a tree or lie in the dirt by the tall entry gate. Ten brothers and their families share the compound, and the children move fluidly through each other’s apartments. Uncle or father, sibling or cousin: it makes little difference. While the stairwells have the provisional, still-under-construction look of dwellings in a constant state of addition, the rooms inside are furnished rather formally: prints of alpine landscapes, velvet-covered sofas, lacy tablecloths. In Ahmed’s bedroom, the sheets have cartoon figures of astronauts. It’s the home of a modestly prosperous clan whose breadwinners run a family-owned grocery store, or work in trades or in transportation.

Until October 12, 2015, Hassan and Ahmed followed the same schedule as all the school-age cousins in the household: go to class, come home, eat, change clothes, and then go play in an area that their uncles had cleared for them on the unused land beneath the highway overpass that separates Beit Hanina from the adjacent neighborhood of Pisgat Ze’ev. Sometimes the cousins played soccer, but Hassan and Ahmed particularly enjoyed training for parkour—the gymnastic running discipline that uses urban space as an obstacle course. The concrete pylons and grassy embankments under the highway were ideal for practicing vaults and tumbles.

The highway divides two East Jerusalem neighborhoods—the House of Hanina and the Peak of Ze’ev—that face each other across a shallow valley. Both are long-settled places. Beit Hanina was home to a few farming families as early as Canaanite times; in Pisgat Ze’ev, excavations have uncovered ritual baths from the Second Temple period.

Both neighborhoods have seen explosive population growth since 1967, when Israel captured this territory from Jordan in the Six-Day War. In the years since, their built-up areas have reached out to each other across land that once supported only olive groves and vineyards. Now the busy highway is all that marks the division between the Palestinian neighborhood and the Jewish one. Pisgat Ze’ev is the last stop on the Jerusalem tramline, Beit Hanina the second-to-last. Residents of the two neighborhoods live cheek by jowl, yet they inhabit two different worlds.

Pisgat Ze’ev, named for the Revisionist Zionist Ze’ev Jabotinsky, was one of the new settlements rapidly built on land annexed by Israel after the war, intended to connect and thicken the Jewish areas of East Jerusalem. Although the annexation remains illegal under international law (the United States, for one, does not recognize it), Pisgat Ze’ev is now one of Jerusalem’s largest neighborhoods, with some forty-two thousand residents, around five hundred of them Palestinians. Shady trees have grown up, softening the lines of its medium-rise, stone-clad apartment blocks and humming commercial areas.

Beit Hanina has grown organically over time from its village origins, and it contains a range of old and new homes. Some thirty-five thousand Palestinians live there, on land Israel has annexed. Another thousand have been severed from their neighbors by the building of the separation barrier a decade ago, after the wave of suicide bombings that characterized the uprising known as the second intifada. The looming concrete wall, which mostly divides annexed land claimed by Israel from occupied land administered by the Israeli military, has huge implications. Those on the Palestinian side may not cross into annexed East Jerusalem—to go to work or school, to visit family, to buy groceries—without a temporary pass issued at the discretion of the Israeli authorities.

On the other side of the barrier, Palestinians have free movement but often face hostility from Jewish hard-liners, whose numbers have grown with Israel’s tilt to the right in recent years. Residents of Beit Hanina sometimes awake to graffiti messages such as “Death to Arabs” and “Jerusalem for Jews” spray-painted on their homes. Cars have been vandalized and burned, tires slashed. Palestinians put the blame on militants from Pisgat Ze’ev. Pisgat Ze’ev residents can be just as quick to blame Palestinians for crimes in their neighborhood.

Not long ago, a Jewish woman accosted the Manasra boys as they practiced parkour under the highway. She accused them of stealing her son’s gloves. The boys’ uncle, also named Ahmed, who was home at the time, was called to the scene. “When I got down there, the boys were looking like scared rabbits, surrounded by settlers and police,” he says. Because of the wave of vandalism, he and his brothers had installed a security camera on the outside of their compound. He suggested the police review the film to see if the boys had left the play area to go and steal in the Israeli neighborhood. The footage proved they’d been playing innocently under the bridge at the time of the alleged theft. The police, he said, accepted the evidence, but the woman continued to accuse and berate the boys. Ahmed Manasra has thought about that incident, and whether the fear it engendered may have been a kind of tipping point for his nephews. “Our children don’t have normal childhoods,” he says. “From the minute they open their eyes they wake into a reality of checkpoints, soldiers, settlers insulting their mom. They see the news from Gaza, children like them, bombed and homeless. They hear about a boy their age, burned alive by Israelis. They are sad and afraid. It’s not a healthy environment.” Even so, he says, he still can’t bring himself to believe that his nephews were capable of doing what they did on an ordinary afternoon in 2015.

It was a Monday, and Hassan came home as usual from his tenth-grade class at Ibn Khaldoun School, where he excelled at his studies and was known for good behavior. Ahmed, who struggled academically and was considered rather young for his age, returned from the nearby New Generation Primary School. Hassan told his mother he was going out to buy a video game for his PlayStation. He asked what she was making for dinner. He was hungry, he told her, and he wouldn’t be gone long. It was about three o’clock in the afternoon.

In CCTV footage captured soon after, Ahmed and Hassan are seen strolling together towards the shopping district of Pisgat Ze’ev, an easy walk from their home once you get across the busy highway. They appear relaxed and unremarkable—two kids out for a walk after school. They amble out of the shot. Then, suddenly, the camera captures a very different image. A young man, wearing the white shirt and black trousers of the Orthodox, runs past the camera, desperately glancing behind him as the two boys, long knives now unsheathed, chase after him. Although Hassan had already stabbed the man, Yosef Ben Shalom, age twenty-one, in the upper body, he managed to outrun them. The boys turned then, and ran on towards the shops on Sisha Asar Street.

Just minutes later, a few blocks away in her top-floor apartment, Ruti Ben Ezra heard three quick pops. A sinewy woman with jet-black hair and cobalt-blue eyes, she came to Israel in 1977 from Argentina when she was eight years old. Ten years later, she served in the army in Gaza during the first intifada, so she had no doubt that what she heard were gunshots. As she rushed down the stairs to see what had happened, she did a mental accounting of the whereabouts of her five children. Two were still at school, two had gone to play football, and one, Ofek, had just left to visit his grandmother. It was Ofek who came barreling back towards the apartment, screaming. “Mum! Mum! Orlev, Na’or … Terrorist!”

“Go upstairs! Close the door!” she told him, and ran out into the road towards the shopping area. A terrified Orlev ran to her. She grasped his hand as he pulled her to the candy store where his older brother Na’or, thirteen, lay sprawled on the sidewalk. Ruti threw herself down beside her son and called his name, begging him to open his eyes. Within minutes, paramedics were at her shoulder, yelling at her to move.

“No!” she said. “I’m his mother!”

“Do you want us to save him? Then get out of the way.”

She stood back as they worked on her unconscious son. Pulse: weak. Blood pressure: plunging. What was evident to the paramedics was that Na’or had been knifed three times, from behind his shoulder. But the amount of blood on the sidewalk didn’t account for his plummeting vital signs. What was not evident: the deadliest of the wounds had punctured his jugular. Internally, invisibly, he was bleeding to death.

A few blocks away, Hassan Manasra was already dead, shot at close range by police officers as he’d rushed at them with his knife. Farther down the tram tracks, his cousin Ahmed lay where a car had struck him. The impact had sent him sprawling, his lower legs twisted up on either side of his body in a grotesque and unnatural shape, like an action figure cast aside by a careless child. Blood pooled around his skull, fractured by the blow from a club wielded by a storekeeper who’d chased him down.

Despite his head injury, he had not lost consciousness. A cell phone video showed his face, contorted, as a mob gathered around him. A voice yelled: “Die, you son of a whore!”

Within hours, that cell phone footage went viral and Ahmed Manasra became a Rorschach blot; a scrim onto which each side of the conflict could project its own narrative.

The Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas was the first to use the boy, erroneously claiming in a televised address that Israelis had summarily executed him. In answer, the Israeli prime minister Bibi Netanyahu released footage of Ahmed in Hadassah Medical Center, head bandaged, being fed pureed food. Palestinians were quick to point out that it was not Israelis offering this succor, but the boy’s Palestinian lawyer, who had noticed the untouched food and realized that Ahmed might not manage to eat it, since his hand was shackled to the bed. On the video, Ahmed is seen raising his free hand, perhaps to shoo the videographer away. An Israeli commentator described the gesture as “an ISIS salute.” Meanwhile, Physicians for Human Rights released a statement decrying the release of the footage as an illegal exposure of the identity of a minor and an unethical violation of patient privacy.

But in this explosive case, privacy didn’t seem respected by either side. A few weeks later, Palestinian television screened a lengthy video of Ahmed’s interrogation. It remains unclear who leaked it. Ahmed sat hunched at a corner of a desk in what appeared to be an Israeli police station, surrounded by three plainclothes officers. The lead interrogator, a brawny man with sunglasses pushed back on top of his knitted kippa, attempted to extract a confession to two counts of attempted murder.

At first, as the interrogator screamed in Arabic and waved his finger in Ahmed’s face, the boy repeatedly hit his injured head.

“I swear by God I can’t remember,” he whimpered.

“You swear by God? Who is this shit God?” Looming over the boy, the interrogator demanded to know why he helped his cousin.

“I don’t know,” Ahmed cried, once again hitting at his head. “Take me to the doctor.”

“Shut up!” yelled the interrogator. “Sit up straight. Put your hands down!”

The film as aired had been edited, so it is impossible to know how long all this went on. But in the end, the boy was sobbing convulsively. “Everything you say is true!” he wailed. “Just stop!”

Since the Manasras live on the Israeli side of the separation barrier, Ahmed Manasra was tried in a civil court rather than under the military justice system, where the conviction rate is 99.74 percent. In Israeli courts, no minor under the age of fourteen at the time of conviction may be sent to prison.

But it was evident from the outset that Ahmed’s case would strain public opinion regarding the protections extended to him. Minors are required to have a parent or an attorney present during questioning. But Ahmed did not. In fact, his parents had difficulty even finding an attorney both qualified and prepared to take his case to trial. One lawyer agreed, and then called the next day to apologize, saying he’d been warned that the case would be a career ender for him. The family finally chose Leah Tsemel, a veteran civil rights attorney who has practiced in Israel’s civil and military courts for over forty-five years.

Tsemel is an Israeli-born Jew whose parents migrated to Israel from Russia and Poland in the 1930s. Raised in Haifa, she served in the army and was studying at university when the Six-Day War broke out, threatening Israel’s survival. During intense fighting in East Jerusalem, she volunteered with the army, evacuating Jewish civilians from the most threatened neighborhoods. When combat was over, the soldiers took her to the newly occupied territory of the West Bank, the biblical lands of Judea and Samaria that had been off limits to Jews during the years of Jordanian rule. The trip was supposed to be a reward, a treat. But the sight of columns of Palestinian refugees trudging down the roadside sickened her, evoking her parents’ stories of European persecutions and the resonance of the homeless, wandering Jew. She was, she said, “naive and apolitical” at that time. “I thought it was a war for peace, that we would use the victory to make peace with our neighbors.” Instead, she soon realized that what she had witnessed was the beginning of occupation, and that even key leaders in the Labor Party had no intention of giving back the land. So, she embraced the far left, and when she graduated from law school went to work in defense of Palestinians. “What I am doing is in Israel’s interest,” she asserts, “even if Israelis don’t realize it.”

Na’or’s mother, Ruti Ben Ezra, is one such Israeli. “Some people will do anything for money, even sell their soul to the devil,” she says. “I hope her own children will be injured or killed by a terrorist.”

Even though Na’or has recovered physically, his parents say his mental scars are far from healed. “The street is his worst enemy,” says his father, Shai, a forty-six-year-old electrician. He says Na’or can’t concentrate at school. His temper has become explosive. “Everything bothers him. He and his brother fight much more than they used to. Orlev feels guilty he ran away and didn’t help his brother.” Shai has had to give up his job because he needs to be with Na’or night and day. He opens his hands in a gesture of helplessness. “We are crushed,” he says.

Ruti, a kindergarten assistant, also has stopped working, afraid to leave her children alone. Two days after the attack on Na’or, her youngest child, age seven, took a knife to school. “The teacher called to tell me,” recalls Ruti. “I didn’t see. I didn’t see that he’d taken it. A seven-year-old shouldn’t have to be so afraid.” And she, too, lives with fear. “Every time I hear a siren, I think, ‘Where are my children?’ In this, they succeeded,” she says. “They want us to be afraid. I’m afraid.”

And that, Ahmed Manasra told his lawyer, Leah Tsemel, when he was finally allowed to see her, was indeed what he had intended. “His cousin said, ‘Let’s go scare them, as they scare us.’ The maximum they intended was to wound. That was the scenario, as they saw it.” Tacitly acknowledging how implausible this version will seem, she shrugs. “They are children,” she says. “But what they did understand, even as children: lifting a knife, they’d probably be killed.”

Ahmed told Tsemel that Hassan had proclaimed he was ready to die, to join the so-called martyrs whose tattered portraits peel off the walls of many Palestinian buildings. But Ahmed says he didn’t feel that way at all. He can’t say why he went along with his older cousin, but once he saw the blood of the first victim, he was terrified. As that man outran them, he saw Hassan glance towards a woman with children. He told Tsemel that he cried out: “Don’t even look at her!” Then Hassan spotted Na’or coming out of the candy store on his bicycle and moved in on him. Ahmed told Tsemel that he cried out “Haram!”—the Arabic word for something unholy, forbidden—“We decided not to!” But Hassan stabbed the boy anyway. Bystanders and storekeepers rushed them, and within a minute or two Hassan was shot dead and Ahmed was bleeding on the tram tracks.