Buch lesen: "The True Darcy Spirit"

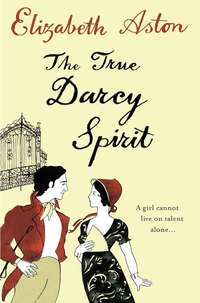

The True Darcy Spirit

Elizabeth Aston

For Paul, with love

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Epilogue

About the Author

Also by Elizabeth Aston

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One

On the forenoon of a hot May day in 1819, two persons were on their way to the Inner Temple. They were almost strangers, but bound by ties of blood and kinship, and in very different situations of life.

Cassandra Darcy was on foot, walking to save the expense of the hackney-coach; the fee of a shilling was more than she could at present afford to spend. Nor, although young and gently bred, was she accompanied by a maid or a footman. Possessed of more than her fair share of good looks, she attracted a good deal of unwelcome attention, yet there was that about her direct look and her straight brows that carried her past even the most loutish of the Londoners going about their business. She was in good time, would, in fact, be early for her appointment.

It wasn’t an encounter she was looking forward to. Not that she had anything to say for or against Mr. Horatio Darcy, but he was her stepfather’s lawyer, and there was no doubt about her feelings toward Mr. Partington. Even though, in all fairness, she couldn’t blame him for the predicament she found herself in. She had been rash, remarkably rash, and must take the blame and endure the consequences of her actions, and, she reflected, any consequences in which her disagreeable stepfather had a hand were likely to be of a most unpleasant nature.

She quickened her pace, as though to escape from the thoughts that crowded into her head. She had to think clearly, this was a time for rational thought and action, and yet feeling would intrude, driving out the clear thoughts that might help her to state her case and come to a reasonable solution of her problems.

Would that reason had played a larger part in her actions these last few weeks, but reason flew out of the window in such cases. She had often heard it said that it was so, but never dreamed that it might one day apply to her. And she, who prided herself on her self-control, had been the one to fling all restraint and sense aside. Her self-control had been her defence against the constant pricks and irritations of life at Rosings, but when she most needed it, it had deserted her.

Well—with an inner sigh—what was done was done. Now she must see how she could make the best of things. She cast a quick glance down at the map in the guidebook that Mrs. Dodd had lent her. It wasn’t clear, and she wasn’t used to maps, but an enquiry of a burly but amiable-looking hackney coachman gave her the right direction, and she turned off the Strand in the direction of the river. The narrow lane led through a noble gateway into the sanctum of the Inner Temple, one of London’s four Inns of Court, where the lawyers belonging to the Inn had their chambers. It was a tranquil and charming place, its grounds stretching to the banks of the Thames and the bustle and hubbub of London no more than a distant murmur.

Cassandra hesitated, looking across the grassy central area to the surrounding buildings. Men in black gowns walked briskly by; clerks, documents tied with ribbon under their arms, hurried past; errand boys, whistling as errand boys always whistled, scurried on their way with messages and parcels.

Here was the staircase where Mr. Darcy had his chambers, here was his name on a wooden panel. Here was a suspicious clerk, demanding to know her name and business, looking behind her for a father, a brother, a footman, a maid.

The clerk had a long, thin nose, red at the tip, the kind of nose that would always have a drip on it come the chills and fogs of autumn. Cassandra didn’t take to him, but then she wasn’t interested in Josiah Henty, clerk; she had come to see Horatio Darcy, lawyer.

And cousin. Distant cousin, she reminded herself. They hardly had more than the name in common, the connection was not at all close. Still, it was a link, and a link she suspected might not please Horatio Darcy just at present.

They had first met when she was a small girl in a smock with her hair tumbling about her shoulders and a smudge on her cheek. He was a great boy in comparison to her, just started at his public school, lanky and self-contained, eight years older than she was. The third son of a younger brother, he was treated with a certain degree of contempt by Cassandra’s grandmother, the formidable Lady Catherine de Bourgh, although with an eye too observant for her years, Cassandra noticed a spark in Horatio’s eye, and she sensed that he wasn’t a whit bothered by Lady Catherine.

She had seen him once more since then, had pelted him with crab apples, in fact. That was when she was twelve, and a tomboy climbing trees during a visit to her cousins at Pemberley, where he was also a visitor. He had looked up, and said what a hoyden she was and gone on his way, tall and still self-contained, with almost as much pride as his cousin Fitzwilliam Darcy, Mama had said, although with much less reason.

“Horatio Darcy does not have an income of ten thousand a year, indeed he has an income of nothing a year, except what his father gives him and what he may earn by his own efforts, nor does he own so much as a cottage, let alone a great estate like Pemberley. They say he is clever; he will need to be to make his way in the world, for even though his father was a Darcy, he was a younger son, and younger sons, you know…” This last with an affected sigh. “As was your dear father, of course.”

Cassandra was less than happy to have her affairs brought under the scrutiny of Horatio Darcy, or indeed any of the Darcy clan. It was her misfortune, she thought, that she was related to the Darcys both through her mother and father. If she had taken her stepfather’s name, as her mother had wanted her to, the Darcys would have had no concern for her present situation, and she might not be sitting here, waiting for her cousin, who was, she noticed with a glance at the clock that hung above the bookshelf opposite, late.

An unpunctual man.

In that case, the Darcys might have been content to shrug shoulders and wash their hands of her: “She always was a headstrong girl, Anne should have brought her up more strictly.”

The thought brought a wry smile to her lips; in many ways it would be difficult to imagine any stricter upbringing than hers, with her stepfather a clergyman with very strict morals indeed, and a naturally overbearing disposition, and her mother always willing to agree with him on the raising of all her children; Cassandra as well as the two daughters and son by her second marriage.

Horatio Darcy was not on foot, but was travelling in an elegant carriage, seated beside the beautiful Lady Usborne. Not that the vehicle moved at much more than a walking pace in the crowded London thoroughfares, and walking fast and purposefully, as was his way, he could have covered the distance from Mount Street, where the Usbornes had their town house, to his chambers at the Inner Temple in much less time than the carriage was taking. He was an active, vigorous man, a young man in a hurry, his enemies said, and certainly not one to idle and linger his way through the day.

Yet here he was, with half the morning spent in a very idle, not to say, dissolute way, that made him no money and brought him no business. Time passed in the arms of the luscious Lady Usborne, although the connection might, at some point, bring him advancement—for the Usbornes were people of wealth and influence—was time wasted as far as his professional life was concerned.

A very pleasant amorous interlude on the chaise longue in her private sitting room, with the door locked against intrusive servants, who were supposed to believe that their mistress had need of yet another lengthy consultation with her handsome young lawyer, had led to a light nuncheon, and then, Lady Usborne declaring that she was driving out, to visit a milliner, it would have been churlish not to accept her request that he might accompany her at least part of the way.

There had been a slightly uncomfortable encounter with Lord Usborne in the hall of his lordship’s town house. The older man was taller and better dressed than Darcy, and a raised eyebrow, a cynical twitch of his lordship’s lip left Darcy feeling ruffled, so that he was anxious to part from Lady Usborne and return to the calmer waters of his chambers.

“Stop here,” he called out to the coachman. A last, swift kiss, and then he jumped down on to the pavement, conscious of the fact that he carried with him the faint aroma of Lady Usborne’s clinging scent, but with a sense of liberation.

He was late for his appointment with Miss Darcy, and he didn’t like to be late. However, it might do this particular client good to kick her heels for a while, waiting could often put an awkward client into an anxious and more amenable frame of mind. Not that she was, strictly speaking, a client. It was a tiresome affair, and one that he had much rather not be mixed up in, but it was right to keep family matters, especially ones of this kind, within the family, where they might be dealt with swiftly and discreetly.

There she was, sitting in the clerk’s room; why the devil hadn’t Henty shown her in? Did he think she was going to snoop among his boxes and papers? Damn it, she was a Darcy, wasn’t she? Although her behaviour might indicate…

He was taken aback as she rose and held out a hand. This assured, poised young woman with her direct look and considerable degree of beauty was not at all what he had been expecting. A fluttering young woman, overcome with guilt, would be more appropriate, or a palefaced, wretched creature, needing masculine support and advice. She certainly didn’t take after her mother, not in appearance. No, he would have known her anywhere for a Darcy, and that irked him. How dare she behave in such a very discreditable way and then appear to be so much in command of herself and of the situation?

When had he last seen her? Nine, ten years ago? At Pemberley, if his memory served him rightly. She had been sitting astride the bow of a tree above his head, hurling crab apples down on him, in a very unfeminine way. He’d been at Westminster School then, not inclined to take any notice of his hoydenish and fortunately distant young cousin.

Horatio Darcy ushered Cassandra into a big, handsome room, with windows overlooking the river. She looked around her, her attention diverted from her problems by the novelty of her surroundings. Shelves lined the walls, crammed with dusty tomes and stacks of papers tied up with faded ribbons. Dozens of boxes were lodged on the topmost shelves, each with a name written on the front in a spidery copperplate too small to decipher. A large desk stood in the centre of the room, and Mr. Darcy placed a chair for her, before retreating to his side of the desk and sitting down with his hands steepled together.

Her cousin had grown into a remarkably handsome man, with a fine, tall figure, but he didn’t look to have become any more amiable in the years that had passed since their last encounter.

“You have come alone?” he asked. “Mr. Eyre is not with you?”

He spoke the name in an icy tone, which made Cassandra wince inwardly. As if the very mention of James Eyre didn’t make her heart turn over. She took a deep breath to make sure none of her emotion showed in her voice or expression. “Mr. Eyre is presently out of the country,” she said. “And this has nothing to do with him.”

Mr. Darcy’s eyebrows shot up. “No? I would have thought his presence was of the first importance in such a matter.”

“If you have summoned me here to talk about Mr. Eyre, then I may tell you at once, that I shall not listen to you.” She began to rise from her seat.

“Sit down,” he said. “To be perfectly correct, I haven’t summoned you, I merely sent you an appointment. It was Mr. Partington, your father—”

“Stepfather.”

“Very well, your stepfather, who asked me to have this interview with you. I question the wisdom of your coming here alone, that is, without Mr. Eyre, because he must surely have a say in what is to be agreed.”

“Nothing is to be agreed that need concern Mr. Eyre.” It caused her a pang to say it, even though it was the simple truth.

“Your marriage to Mr. Eyre is only one of the matters that has to be discussed, but since it is the key to everything else, let us discuss that first.”

“There is nothing to discuss with regard to any marriage between Mr. Eyre and me. I told Mr. Partington how matters stood. If he chooses to disbelieve me, then that is his own affair.” She took another deep breath, she must not show how fragile was her self-possession. “I received a message from you asking me to wait upon you on a matter of business. I did not expect to have my private affairs raked over by you.”

“I am a lawyer, acting for your father.”

“Stepfather.”

“I also have the honour to be a member of the family to which you yourself belong. You bear an ancient and an honourable name, and since you seem determined to drag it in the dust, it is the duty of all the male members of your family to point out to you how wrong is your wilful decision not to marry Mr. Eyre.”

“It is odd,” Cassandra remarked in a conversational tone, “how everyone now is wild for me to marry Mr. Eyre, whereas only a few weeks ago, it was the last outcome that my family wished.”

“That was before you ran away with the gentleman in question,” said Mr. Darcy coldly.

“Eloped,” Cassandra said.

“Elopements end in marriage, not in cohabitation in London lodgings.”

Cassandra flushed, hating to have her connection with James spoken of in those terms, although God knew, Mr. Darcy was right. She felt she must defend herself. “When I left Bath in the company of Mr. Eyre, it was on the assumption that we were heading for Gretna Green, where we would be married under Scottish law.”

“That was not, however, the case, and you were perhaps naïve to assume any such thing. By putting yourself in the power of a man such as Mr. Eyre, you surely must have been aware that you were laying yourself open to all kinds of dangers.”

“You do not know Mr. Eyre, I believe? So pray do not speak of him in those terms. I and Mr. Eyre have…” Despite herself, her voice faltered. “We have parted, but even so…” She paused, and frowned, her eyes fastened on the floor. Then she raised them to look directly at her cousin. “Have you ever been in love, Mr. Darcy?”

Horatio Darcy was thunderstruck. “What did you say?”

“I asked if you had ever been in love. If not, you may be unable to understand how things were between Mr. Eyre and me. I believed then that he was a man I could trust in every way.”

“If your relationship was as amiable and trusting as your words imply, then it came to a very unfortunate outcome.”

“When one is in love—”

“Love, Cassandra, has no place in a lawyer’s office.”

“There, I felt sure that you had never fallen head over heels in love, or you would be less disapproving of my behaviour.”

“My personal life has no bearing on this whatsoever. The case is simple. You ran away from the protection of your family, you were under the care of your aunt—”

“Of my stepfather’s sister, in fact.”

“Very well, of Mrs.”—he glanced down at the paper in front of him—“Cathcart, who stood in loco parentis to you, I believe, your mother and stepfather having placed you in her care. As I say, you ran away from her house in Bath, and put yourself under the protection of an unmarried man. With whom you lived on terms of intimacy—”

“As man and wife, in fact.”

“—terms of intimacy, with, apparently, no concern as to the irregularity of your union.”

The words were beginning to anger Cassandra, chasing away the surge of unhappiness that swept over her when she thought and spoke of James, of what he had meant to her, of how it had ended. Irregularity of their union; what cold, unfeeling words! True, it was a union unsanctified by church or state, but they had fallen in love, had chosen one another as their life’s companion—or so she had thought—and did a few days or weeks make so very much difference, even in the eyes of God?

She should have known how it would end, of course; from the moment the coach bowling out of Bath took the London road instead of the road to the north, she should have known that Mr. Eyre had quite a different scheme in mind from what was planned.

Never for a moment had she doubted his love for her, any more than she doubted her own affections. But prudence had appeared from nowhere, a prudence and a caution she would never have expected in the gallant officer who had swept her off her feet.

“It will be better to tie the knot when the arrangements have been made with your family,” James had said, leaning forward in the carriage, so that she could not see his face.

Arrangements. Money, of course, it was money that lay at the heart of his stepping back from an immediate marriage, although prudence hadn’t kept him out of her bed.

“I dare say,” he had said, succumbing to his passions just as she did, “that this will make it harder for your family to send me packing.”

He didn’t know her stepfather, and so it had ended, not at the altar, but in this lawyer’s room, with her cousin’s words recalling her to the present.

“I would be grateful for your attention,” Horatio said drily. “Under the terms of your late grandmother’s will—”

“I know the terms of the will. Rosings and the land and property naturally go to my brother. I, and my two sisters, are to be provided, upon our marriages, with such fortunes as Mama and my stepfather see fit. One hundred and fifty thousand pounds was set aside for our dowries.”

“Of which—”

“Of which, my stepfather was prepared to give me not a penny, and on that basis, Mr. Eyre declared he would not marry me. Now he says he will take me with twenty thousand pounds, and the family, to which you have the honour to belong, has put a great deal of pressure on my stepfather to agree to this. The settlements are drawn, the bridals may take place as soon as possible.”

Horatio looked at Cassandra with cold distaste. “I see you like to come to the heart of the issue.”

“I do.”

“Yet, having thrown yourself into the arms of this man, whom you claim to love, you now refuse to marry him.”

“There are other conditions, I believe.”

Horatio Darcy looked down at his papers, flicked through them, and took one up. “There are. First, the marriage is to take place discreetly, in London. Second, Mr. Eyre is to leave the navy. Third, immediately you have exchanged your vows, you are to leave the country and spend at least the next twelve months abroad, in Switzerland, where a house will be provided for you. On return to this country, you will live out of London, and at some distance from both Kent and Derbyshire.”

From Derbyshire? “Is the great Mr. Darcy of Pemberley really afraid that my residing there would pollute his neighbourhood?”

“This condition comes from your mother. She does not wish you to associate in any way with any member of your family after your marriage. You will not be allowed to visit Rosings, nor to communicate with your brother and sisters.”

“Half brother and half sisters.”

“I can see you might find these conditions onerous—”

“Outrageous, I would say, but it does not matter how they are to be described. Since I will not marry Mr. Eyre, the rest has no relevance.”

“Let me continue. If you persist in your stubborn refusal to marry Mr. Eyre, then you have two choices. I tell you this, since I have been instructed to do so; however, I feel sure that your good sense and your duty to your family will lead you to make the only proper decision, of agreeing that the marriage will take place. If not, then your mother and f—stepfather have decided that you must live out of the world. You are ruined, you have lost your good name, and for your own protection and for the sake of those connected with you, you need to live quietly, out of the public eye, and a long way from your immediate family, so that this fatal step you have taken may, in time, be forgotten.”

“Where is this place of retirement to be? Ireland? Some remote part of the Scottish Highlands? Or perhaps abroad? I believe English people who are ruined often go to live in Calais.”

“Those are people who face financial ruin.”

“You mean I won’t?”

Horatio Darcy’s voice was growing colder by the minute, and it gave Cassandra some satisfaction to see that she was needling him.

“I may say that your levity, at such a time, is ill-assumed, Miss Darcy. Perhaps you could restrain yourself and allow me to finish what I have to say. The accommodation your parents have in mind is to live under the care of one Mrs. Norris—ah, I see you recognize the name—who presently resides in Cheltenham, in the company of the disgraced Mrs. Rushworth, Maria Bertram as was, who, like you, took a step that removed her irrevocably from the company and society that her birth and upbringing entitled her to.”

Nothing this man had said so far had sent such a chill with her. That would be a punishment indeed; she had heard much about Mrs. Norris from her stepfather, and knew her for a cold-hearted woman with a mean temper and narrow outlook. She could scarcely imagine a worse fate. “Live with Mrs. Norris! You cannot be serious.”

“I am perfectly serious.”

“Well, whatever happens, I will not do so. You said I had two choices; pray, what is the second?”

“If you will neither marry nor go to live with Mrs. Norris, then your family, your mother, and stepfather wash their hands of you. You have, I understand, a small income from your late aunt of some ninety pounds per annum. This will be paid to you quarterly, and your parents will never see nor speak to you again.”

Cassandra couldn’t help it; tears were welling in her eyes. She dug in her reticule, took out a small lace handkerchief, and blew her nose.

“Allow me,” Horatio said, getting up and handing her a clean and much larger handkerchief. She waved it away, unable to bring herself to speak.

“Don’t be foolish. Take it. I am not surprised you are upset, for this is a very harsh treatment. However, I would point out that there are parents who would choose such a rejection of a daughter who has behaved as you have done, without offering what I think are very generous alternative arrangements.”

The desolation in Cassandra’s heart almost overwhelmed her, and she strove to compose herself, with the result that her words sounded, even to her ears, cold and uncaring. “I cannot marry Mr. Eyre. I will not marry a man who doesn’t love me enough to marry me without a fortune or my family’s approval. And I cannot consent to a life of misery such as would be mine were I to live under the same roof as Mrs. Norris.”

“Then you must resign yourself to a single life, knowing every day that you have incurred the wholehearted disapproval of every single member of your family, close and distant, and that you are cast off from everything you have known up until now: a home, the affection and concern of those nearest to you, and the life of a young girl of good family and fortune. There are places where you can live on ninety pounds a year, but it would not permit your residence in London, for example.”

“I shall have to earn my living, I can see, just as you do.”

He looked affronted. “I hardly think that any duties you may undertake to augment your income are on a par with my profession. Besides, with a tarnished reputation and no references, you will find it very hard to secure employment of any kind. To be brutally frank, the future that awaits you is far more likely to be that you will come upon the town.”

“You do indeed have a low opinion of my morals if you assume that I would ever become one of those women.”

“I am a realist. I know what London is, that is all, and what is the fate of most women in your situation. My recommendation to you, should you commit yourself to an independent life, is that you move to a provincial town where you may live quietly and inexpensively.”

“Could not you give me a reference, so that I might find respectable employment?”

“Certainly not.”

“I thought, the very first time I met you, that you had a kindness about you. I remember you picking me up when I fell off my pony, and defending me against my governess’s wrath. I see that I was mistaken.” Cassandra got up.

“I do not expect you to give me an answer now. I am instructed to allow you a week to—”

“Come to my senses, is that what my stepfather says? Believe me, Mr. Darcy, I do not need three minutes to make my decision.”

Horatio hesitated. “Speaking, not as a lawyer, but as your cousin, Cassandra, and as a man who has lived in London long enough to know what a terrifying place it can be to those cast adrift upon it, I beseech you to think most carefully what you are about.”

“You are worried lest a Miss Darcy be known to have joined the impures, is that it?”

“Really, I do think…Cassandra, you have no idea what it means to come upon the town!”

“You may set your mind at rest. I shall not use the name of Darcy from now on. My family casts me off; very well, I do the same to them.”

Cassandra went slowly down the staircase from Mr. Darcy’s chambers, blinking as she came out of the shadows into the bright sunlight. She felt numb, as though all power of sensation had drained away from her. Her mind, though, was far from numb, and indeed she saw the outside world with an extra clarity; grass, pathways, trees, figures all as though they had been outlined with a sharp pen.

In that brief half hour within Mr. Darcy’s chambers, her life had changed. A door had shut behind her and she was excluded from every part of her life that she had formerly known. Why should she feel this now, and not think that her old life had ended some other critical moment? Why not when she had left Rosings; now, as she knew, for the last time? Why not when she had arrived in Bath, or left it, with James? Why not when she had reached London, and had spent a night in his arms?

It was, her mind told her, because, in those chambers, she had made the decision. It was not circumstances or chance or the authority or advice of a parent or a lover—or, indeed, of a lawyer—that had, inside that room, laid down the pattern of her future life. It owed nothing to any other being, only to herself.

She walked away across the green towards the broad gravel walk that ran alongside the river. On such a fine day, there were several people promenading up and down beside the river; it was a favourite spot for Londoners, the clerk had grudgingly informed her. She watched a middle-aged couple strolling along, the man in a brown hat and his wife holding a parasol at an elegant angle to shield her complexion from the sun. A pair of young women walked arm in arm, laughing and talking together, the feathers on their hats fluttering in the slight breeze, their muslin skirts playing around their ankles as they walked. One of them was leading a little dog that pranced along on its short legs, excited to be out and snuffing the smells of the river bank.

Not being a Londoner, and having spent no more than a few hours in her whole life in the capital before she came there with James Eyre, Cassandra had never seen the Thames. James, learning this, and laughing at her for being a mere country girl, had taken her to see the river on their first morning in London, and she had been entranced by the teeming waterway.

“It is never twice the same,” he told her, and she had seen it dark under grey skies with him, and now, gleaming and glinting under a blue sky, with the sun shining upon it. She stood and watched strings of barges under sail going up and down, and the watermen plying their trade and calling to one another across the water. These moving craft made their way among a forest of masts, more than three thousand, James had said, amused at her amazement, promising that they would take a day out on the river, travel up to Kew to visit the botanic gardens, or ride to Richmond.