Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "The Woman of Substance"

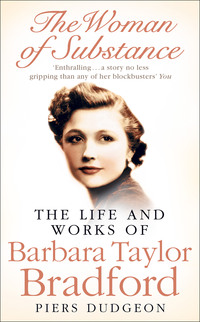

The Woman of Substance

THE SECRET LIFE THAT INSPIRED

THE RENOWNED STORYTELLER

Barbara Taylor Bradford was born and raised in England. She started her writing career on the Yorkshire Evening Post and later worked as a journalist in London. Her first novel, A Woman of Substance, became an enduring bestseller and was followed by twenty-five others, including the bestselling Harte series. Barbara’s books have sold more than eighty-one million copies worldwide in more than ninety countries and forty languages, and ten mini-series and television movies have been made of her books. In October of 2007, Barbara was appointed an OBE by the Queen for her services to literature. She lives in New York City with her husband, television producer Robert Bradford.

Piers Dudgeon is the author of many works of nonfiction. He worked for ten years as an editor in London, before starting his own publishing company and producing books with authors as diverse as John Fowles, Catherine Cookson, Peter Ackroyd, Daphne du Maurier, Shirley Conran, Ted Hughes and Susan Hill. In 1993, he left London for the North York Moors, where he has written biographies of Sir John Tavener, Edward de Bono, Catherine Cookson, Josephine Cox, J M Barrie and Daphne du Maurier. He is currently working on a series of oral histories of post-industrial Britain and a book about the poet Ted Hughes’s childhood.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

List of Illustrations

Preface

PART ONE

The Party

Beginnings

Edith

The Abyss

PART TWO

A New Start?

Getting On

The Jeannie Years

Change of Identity

Coming Home

An Author of Substance

Hold the Dream

Novels by Barbara Taylor Bradford

Index

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Section 1

1. Barbara’s mother, Freda Walker, a nurse at Ripon Fever Hospital in 1922. (Bradford Photo Archive)

2. Freda in her early twenties with Tony Ellwood, the child she brought up in Armley, Leeds, before marrying Winston Taylor. (Bradford Photo Archive)

3. Winston Taylor, Barbara’s father as a boy of sixteen in the Royal Navy. (Bradford Photo Archive)

4. Winston’s sister, Laura, the model for Laura Spencer in A Woman of Substance. (Bradford Photo Archive)

5. Map of Armley, dated 1933, the year Barbara was born.

6. Barbara’s parents, Winston and Freda Taylor in 1929, the year they were married. (Bradford Photo Archive)

7. Barbara at two years, walking in Gott’s Park, Armley. (Bradford Photo Archive)

8. Tower Lane, Armley, site of Barbara’s first home.

9. No. 38 Tower Lane as it is today.

10. The Towers, the gothic row of mansions in Tower Lane, one of which became Emma Harte’s home in A Woman of Substance.

11. Armley Christ Church School, which Barbara attended with playwright Alan Bennett.

12. Freda and daughter Barbara – ‘the kind of little girl who always looked ironed from top to toe’. (Bradford Photo Archive)

13. Barbara aged three. (Bradford Photo Archive)

14. Christ Church Armley, where Barbara was baptised and received her first Communion.

15. Barbara as a fairy in a Sunday School pantomime. (Bradford Photo Archive)

16. Barbara with bucket and spade, aged five on holiday at Bridlington. (Bradford Photo Archive)

17 and 18. Leeds Market, where Marks & Spencer began and the food halls in Emma Harte’s flag-ship store in A Woman of Substance were inspired. (Yorkshire Post and Leeds Library)

19. Top Withens, the setting for Wuthering Heights. (Yorkshire Tourist Board)

20. ‘The roofless halls and ghostly chambers’ of Middleham Castle, North Yorkshire. (Skyscan Balloon Photography, English Heritage)

Section 2

21. 1909 Map of Ripon, when Barbara’s mother, Freda, was five.

22. Ripon Minster. (Ripon Library)

23. Ripon Market Place as Freda and her mother, Edith, knew it. (Ripon Library)

24. The Wakeman Hornblower, who still announces the watch each night at 9 p.m. (Ripon Library)

25. Water Skellgate in 1904, the year that Edith Walker gave birth there to Freda. (Ripon Library)

26. The stepping stones on the Skell where Freda fell. (Ripon Library)

27. One of Ripon’s ancient courts, like the one where Freda was born.

28. Freda dressed in her best at fourteen. (Bradford Photo Archive)

29. Studley Royal Hall, home of the Marquesses of Ripon. (Ripon Library)

30. Fountains Hall, on which Pennistone Royal in the Emma Harte novels is based. (Ripon Library)

31. Edith Walker, Barbara’s maternal grandmother. (Bradford Photo Archive)

32. Frederick Oliver Robinson of Studley Royal, Second Marquess of Ripon. (Ripon Library)

33. Ripon Union Workhouse, known as the Grubber in Edith’s day.

Section 3

34 and 35. The offices of The Yorkshire Evening Post, where Barbara worked from fifteen. (Yorkshire Post)

36. Barbara as YEP Woman’s Page Assistant at seventeen. (Bradford Photo Archive)

37. Barbara at nineteen, as Woman’s Page Editor. (Bradford Photo Archive)

38. Barbara’s sometime colleague, Keith Waterhouse, the celebrated commentator, playwright and author, with his collaborator, playwright Willis Hall. (Yorkshire Post)

39. Barbara in 1953, aged twenty, when she left Leeds for London to work as a Fashion Editor on Woman’s Own. (Bradford Photo Archive)

40. Peter O’Toole with Omar Sharif in Lawrence of Arabia. (Columbia Pictures)

41. Barbara’s husband, film producer Robert Bradford. (Bradford Photo Archive)

42. Barbara after her uprooting to New York. (Cris Alexander/Bradford Photo Archive)

43. Barbara’s mother, Freda Taylor, a long way from home on Fifth Avenue, New York.

44. Barbara, the writer. (Bradford Photo Archive)

45. Barbara, multi-million-selling author of A Woman of Substance. (Cris Alexander/Bradford Photo Archive)

Section 4

46. Robert Bradford with the book that realised a dream. (Bradford Photo Archive).

47. Jenny Seagrove as Emma Harte, the woman of substance. (Bradford Photo Archive)

48. Deborah Kerr takes over as the older Emma, with Sir John Mills as Henry Rossiter, Emma’s financial adviser. (Bradford Photo Archive)

49. Stars of To Be the Best, Lindsay Wagner and Sir Anthony Hopkins. (Bradford Photo Archive)

50. Barbara with the stars of To Be the Best, Fiona Fullerton, Lindsay Wagner, Christopher Cazenove and Sir Anthony Hopkins (Bradford Photo Archive)

51. Victoria Tenant as Audra Crowther and Kevin McNally as Vincent Crowther in Act of Will. (Odyssey Video from the DVD release Act of Will)

52. Barbara’s bichons frises, Beaji and Chammi. (Bradford Photo Archive)

53. Alan Bennett and Barbara receiving the degree of Doctor of Letters from Leeds University in 1990. (Yorkshire Post)

54. Barbara with Reg Carr, sometime Keeper of the Barbara Taylor Bradford archive at the Brotherton Library in Leeds. (Bradford Photo Archive)

55. Barbara Taylor Bradford by Lord Lichfield. (Bradford Photo Archive)

PREFACE

Exploring one of the world’s most successful writers through the looking glass of her fiction is an idea particularly well suited in the case of Barbara Taylor Bradford, whose fictional heroines draw on their creator’s character and chart the emotional contours of her own experience, and whose own history so often emerges from the shadowland between fact and fiction.

She turned out to be unstintingly generous with her time, advising me about real-life places, episodes and events in the novels, despite a hectic round of her own, which included the writing of two novels, the launch of her nineteenth novel, Emma’s Secret (2003), a high-profile legal action in India against a TV film company suspected of purloining her books and films, a grand party celebrating a quarter of a century with publishers HarperCollins, and a schedule of charity events, which film producer, business manager and husband Robert Bradford arranged for her – oh, and a week or so’s holiday.

Barbara’s first novel, A Woman of Substance, is, according to Publishers Weekly, the eighth biggest-selling novel ever to be published. It has sold more than twenty-five million copies worldwide. In it, so reviewers will tell you, we have the classic Cinderella story. Emma Harte rises from maid to matriarch; the impoverished Edwardian kitchen maid comes, through her own efforts, to rule over a business empire that stretches from Yorkshire to America and Australia.

What it took to escape the constraints of the Edwardian and later twentieth-century English class system is at the heart of Barbara’s family’s own story too. Her rise to bestselling novelist and icon for emancipated womanhood, currently valued at some $170 million, from a two-up two-down in Leeds is by any standard extraordinary. Her elevation coincided with the post-war drift from an Edwardian upstairs/downstairs class system (into which Barbara’s mother Freda was born), reconstructed by socialism in the period of Barbara’s own childhood, to one ultimately sensible to merit, a transformation which finds symbolic incidence in the year 1979, in which A Woman of Substance was first published and that champion of meritocracy, Margaret Thatcher, who had risen from the lower middle classes to become Britain’s first female Prime Minister, arrived at No. 10 Downing Street.

Barbara’s novels, which encourage women to believe they can conquer the world, whatever their class or background and despite the fact that they are operating in a man’s domain, tapped into the aspirational energy of this era and served to expedite social change. Indeed, it might be said that Barbara Taylor Bradford would have invented Margaret Thatcher if she had not already existed. When they met, there was a memorable double take of where ambition had led them. ‘I was invited to a reception at Number Ten,’ Barbara recalls. ‘I saw a picture of Churchill in the hall outside the reception room and slipped out to look at it. Mrs Thatcher followed me out and asked if I was all right. I just said: “I never thought a girl from Yorkshire like me would be standing here at the invitation of the Prime Minister looking at a portrait of Churchill inside ten Downing Street,” and she whispered: “I know what you mean.”’

More intriguingly, in the process of writing fiction, ideas arise which owe their genesis not to the culture of an era, but to the author’s inner experience, and here, as any editor knows, lie the most compelling parts of a writer’s work. Barbara is the first to agree: ‘It’s very hard when you’ve just finished a novel to define what you’ve really written about other than what seems to be the verity on paper. There’s something else there underlying it subconsciously in the writer’s mind, and that I might be able to give you later.’ She promised this to journalist Billie Figg in the early 1980s, but never delivered, though the prospect is especially enticing, given that she can also say: ‘My typewriter is my psychiatrist.’

There is no pearl without first there being grit in the oyster. The grit may lie in childhood experience, possibly only partly understood or deliberately blanked out, buried and unresolved by the defence mechanisms of the conscious mind. Unawares, the subconscious generates the ideas that claw at a writer’s inner self and drive his or her best fiction.

Barbara shies away from such talk, denouncing inspiration – it is, she says, something that she has never ‘had’. She admits that on occasion she finds herself strangely moved by a place and gets feelings of déjà vu, even of having been part of something that happened before she was born, but mostly she sees herself as a storyteller, a creator of stories, happy to draw on her own life, all of it perfectly conscious and practical. Later we will see how she works up a novel out of her characters, which is indeed a conscious process. But subconscious influences are by their very nature not known to the conscious mind, and we will also see that echoes of a past unknown do indeed inhabit her writing.

Barbara will tell you that it was her mother, Freda, who made her who she is today. Mother and daughter were so close, and Freda so determined an influence, that their relationship reads almost like a conspiracy in Barbara’s future success. Freda was on a mission, ‘a crusade’, but it wasn’t quite the selfless mission that Barbara supposed, for Freda had an agenda: she was driven to realise ambition in her daughter by a need to resolve the disastrous experiences of her own childhood, about which Barbara, and possibly even Freda’s husband, knew nothing.

In fact, Barbara’s story turns out to be an inextricable part of the story of not two but three women – herself, her mother Freda, and Freda’s mother, Edith, whose own dream of rising in the world turned horribly sour when the man she loved failed her and reduced her family to penury. It left her eldest daughter Freda with enormous problems to resolve, and a sense of loss which, on account of her extraordinarily close relationship with Barbara, found its way into the novels. One might even say that in resolving it in the lives of her characters Barbara appeased Freda and, in her material success, actually realised Edith’s dream.

Barbara told me very little about her mother and grandmother before I began writing this book, and as my own research progressed I had to assume that she did not know their incredible story. If she had known, surely she would have told me. If she had not wanted me to know, why set me loose on research geared to finding out? At the end, when I showed her the manuscript, her shock confirmed that she had not known, and she found it very difficult to accept that she had written about these things of which she had no conscious knowledge.

That the novels own something of which their creator is not master, to my mind adds to their magic, the subconscious process signifying Freda’s power over Barbara, which Barbara would not deny. She may not have been aware of all that happened to Freda, but she was ‘joined at the hip’, as she put it, to one who was aware.

No one was closer to Barbara at the most impressionable moments of her life than Freda. They were inseparable, and the child’s subconscious could not have failed to imbibe a sense of what assailed her mother. Even if Freda withheld the detail, or Barbara blanked it out, the adult Barbara allows an impression of ‘a great sense of loss’ in Freda, which is indeed the very feeling that so many of her fictional characters must overcome.

Freda’s legacy of deprivation – her loss – became the grit around which the pearls of Barbara’s success were layered. So closely woven were the threads of these three women’s lives that Barbara’s part in the plot – the end game, the novels – seems in a real sense predestined. In reality, everything in Freda’s history, and that of Edith’s, required Barbara to happen. In the garden of her fiction, they are one seed. None is strictly one character or another, although Barbara regards Freda as most closely Audra Kenton in Act of Will. Nevertheless, their preoccupations are what the novels are about.

Of secrets, she writes in Everything to Gain, ‘there were so many in our family . . . I never wanted to face those secrets from my childhood. Better to forget them; better still to pretend they did not exist. But they did. My childhood was constructed on secrets layered one on top of the other.’ In Her Own Rules, Meredith Stratton quantifies the challenge of the project: ‘For years she had lived with half-truths, had hidden so much, that it was difficult to unearth it all now.’

Secrets produce rumour, which challenges the literary detective to run down the truth at the heart of the most fantastic storylines. Known facts act like an adhesive for the calcium layers of fictional storyline which make up the ‘pearl’ that is the author’s work. These secrets empower Barbara’s best fiction. They find expression in the desire for revenge, which Edith will have felt and which drives Emma Harte’s rise in A Woman of Substance. They find expression in the unnatural force of Audra Kenton’s determination in Act of Will that her daughter Christina will live a better life than she, and in the driving ambition of dispossessed Maximilian West in The Women in His Life.

My project is not, therefore, as simple as matching Barbara’s character with the woman of substance she created in the novels, but I believe it takes us a lot closer to explaining why A Woman of Substance is the eighth biggest-selling novel in the history of the world than merely observing such a match or studying the marketing plan. That is not to belittle the marketing of this novel, which set new records in the industry; nor is it to underestimate the significance of the timing of the venture; nor to underrate the talents of the author in helping fashion Eighties’ Zeitgeist.

It is just that these ‘secrets’, which come to us across a gulf of one hundred years, have exerted an impressive power in the lives of these women, and although we live in a time when the market rules, deep down we still reserve our highest regard for works not planned for the market but which come from just such an elemental drive of the author, especially when, as in the case of A Woman of Substance, that drive finds so universal a significance among its readers in the most pressing business of our times – that of rising in the world.

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

The Party

‘The ambience in the dining room was decidedly romantic, had an almost fairytale quality . . . The flickering candlelight, the women beautiful in their elegant gowns and glittering jewels, the men handsome in their dinner jackets, the conversation brisk, sparkling, entertaining . . .’

Voice of the Heart

The Bradfords’ elegant fourteen-room apartment occupies the sixth floor of a 1930s landmark building overlooking Manhattan’s East River. The approach is via a grand ground-floor lobby, classical in style, replete with red-silk chaise longues, massive wall-recessed urns, and busy uniformed porters skating around black marbled floors.

A mahogany-lined lift delivers visitors to the front door, which, on the evening of the party, lay open, leaving arrivals naked to the all-at-once gaze of the already gathered. Fortunately I had been warned about the possibility of this and had balanced the rather outré effect of my gift – a jar of Yorkshire moorland honey (my bees, Barbara’s moor) – by cutting what I hoped would be a rather sophisticated, shadowy, Jack-the-Ripper dash with a high-collared leather coat. If I was successful, no one was impolite enough to mention it.

One is met at the door by Mohammed, aptly named spiriter away of material effects – coats, hats, even, to my chagrin, gifts. Barbara arrives and we move swiftly from reception area, which I would later see spills into a bar, to the drawing room, positioned centrally between dining room and library, and occupying the riverside frontage of an apartment which must measure all of five thousand square feet.

The immediate impression is of classical splendour – spacious rooms, picture windows, high ceilings and crystal chandeliers. These three main rooms, an enfilade and open-doored to one another that night, arise from oak-wood floors bestrewn with antique carpets, elegant ground for silk-upholstered walls hung with Venetian mirrors, and, as readers of her novels would expect, a European mix of Biedermeier and Art Deco furniture, Impressionist paintings and silk-upholstered chairs.

This is not, as it happens, the apartment that she draws on in her fiction. The Bradfords have been here for ten years only. Between 1983 and 1995 they lived a few blocks away, many storeys higher up, with views of the East River and exclusive Sutton Place from almost every room. But it was here that Allison Pearson came to interview Barbara in 1999, and, swept up in the glamour, took the tack that from this similarly privileged vantage point it is ‘easy to forget that there is a world down there, a world full of pain and ugliness’, while at the same time wanting some of it: ‘Any journalist going to see Barbara Taylor Bradford in New York,’ she wrote, ‘will find herself asking the question I asked myself as I stood in exclusive Sutton Place, craning my neck and staring up at the north face of the author’s mighty apartment building. What has this one-time cub reporter on the Yorkshire Evening Post got that I haven’t?’ It was a good starting point, but Allison’s answer: ‘Well, about $600 million,’ kept the burden of her question at bay.

Before long the river draws my gaze, a pleasure boat all lit up, a full moon and the clear night sky, and even if Queens is not exactly the Houses of Parliament there is great breadth that the Thames cannot match, and a touch of mystery from an illuminated ruin, a hospital or sometime asylum marooned on an island directly opposite. It is indeed a privileged view.

Champagne and cocktails are available. I opt for the former and remember my daughter’s advice to drink no more than the top quarter of a glass. She, an American resident whose childhood slumbers were disturbed by rather more louche, deep-into-the-night London dinner parties, had been so afeared that I would disgrace myself that she had earlier sent me a copy of Toby Young’s How To Lose Friends & Alienate People.

I find no need for it here. People know one another and are immediately, but not at all overbearingly, welcoming. In among it all, Barbara doesn’t just Europeanise the scene, she colloquialises it. For me that night she had the timbre of home and the enduring excitement of the little girl barely out of her teens who had not only the guts but the joie de vivre to get up and discover the world when that was rarely done. She is fun. I would have thought so then, and do so now, and at once see that no one has any reason for being here except to enjoy this in her too.

It is a fluid scene. People swim in and out of view, and finding myself close to the library I slip away and find a woman alone on the far side of the room looking out across the street through a side window. Hers is the first name I will remember, though by then half a dozen have been put past me. I ask the lady what can possibly be absorbing her. I see only another apartment block, more severe, brick built, stark even. ‘I used to live there,’ she says. ‘My neighbour was Greta Garbo . . . until she died.’ This, then, was where the greatest of all screen goddesses found it possible finally to be alone, or might have done had it not been for my interlocutor.

‘Where do you live now?’ I venture.

She looks at me quizzically, as if I should know. ‘In Switzerland and the South of France. New York only for the winter months.’

Then I make the faux pas of the evening, thankful that only she and I will have heard it: ‘What on earth do you do?’

Barbara swoops to rescue me (or the lady) with an introduction. Garbo’s friend is Rex Harrison’s widow, Mercia. She does not do. Suddenly it seems that I have opened up the library; people are following Barbara in. I find myself being introduced to comedienne Joan Rivers and fashion designer Arnold Scaasi, whose history Barbara peppers with names such as Liz Taylor, Natalie Wood, Joan Crawford, Candice Bergen, Barbra Streisand, Joan Rivers of course, and, as of now, all the President’s women. Barbara and movie-producer husband Bob are regular visitors to the White House.

It is November 2002 and talk turns naturally to Bob Woodward’s Bush at War, which I am told will help establish GB as the greatest president of all time. I am asked my opinion and once again my daughter’s voice comes like a distant echo – her second rule: no politics (she knows me too well). Barbara has already told me that she and Bob know the Bush family and I just caught sight of a photograph of them with the President on the campaign trail. They are Republicans. When I limit myself to saying that I can empathise with the shock and hurt of September 11, that I had a friend who died in the disaster, but war seems old-fashioned, so primitive a solution, Barbara takes my daughter’s line and confesses that she herself makes it a rule not to talk politics with close friend Diahn McGrath, a lawyer and staunch Democrat, to whom she at once directs me.

Barbara is the perfect hostess, this pre-dinner hour the complete introduction that will allow me to relax at table, even to contribute a little. There’s a former publishing executive, one Parker Ladd, with the demeanour of a Somerset Maugham, or possibly a Noel Coward (Barbara’s champagne is good), who tells me he is a friend of Ralph Fields, the first person to give me rein in publishing, and who turns out – to my amazement – still to be alive.

So, even in the midst of this Manhattan scene I find myself comfortable anchorage not only in contact through Barbara with my home county of Yorkshire, but in fond memories of the publishing scene. It was not at all what I had expected to find. I am led in to dinner by a woman introduced to me as Edwina Kaplan, a sculptor and painter whose husband is an architect, but who talks heatedly (and at the time quite inexplicably) about tapes she has discovered of Winston Churchill’s war-time speeches. Would people be interested? she wonders. Later I would see a couple of her works on Barbara’s walls, but for some reason nobody thought it pertinent until the following day to explain that Edwina was Sir Winston’s granddaughter, Edwina Sandys. Churchill, of course, is one of Barbara’s heroes; in her childhood she contributed to his wife Clementine’s Aid to Russia fund and still has one of her letters, now framed in the library.

The table, set for fourteen, is exquisite, its furniture dancing to the light of a generously decked antique crystal chandelier. The theme is red, from the walls to the central floral display through floral napkin rings to what seems to be a china zoo occupying the few spaces left by the flower-bowls, crystal tableware and place settings. Beautifully crafted porcelain elephants and giraffes peek out from between silver water goblets and crystal glasses of every conceivable size and design.

There are named place-cards and I begin the hunt for my seat. I am last to find mine, and as soon as I sit, Barbara erupts with annoyance. She had specially chosen a white rose for my napkin ring – the White Rose of Yorkshire – which is lying on the plate of my neighbour to the right. Someone has switched my placement card! Immediately I wonder whether the culprit has made the switch to be near me or to get away, but as I settle, and the white rose is restored, my neighbour to the left leaves me in no doubt that I am particularly welcome. She tells me that she is a divorce lawyer, a role of no small importance in the marital chess games of the Manhattan wealthy. How many around this table might she have served? Was switching my place-card the first step in a strategy aimed at my own marriage?

I reach for the neat vodka in the smallest stem of my glass cluster and steady my nerves, turning our conversation to Bob and Barbara and soon realising that here, around this table, among their friends, are the answers to so many questions I have for my subject’s Manhattan years. I set to work, both on my left and to my right, where I find Nancy Evans, Barbara’s former publisher at the mighty Doubleday in the mid-1980s.

By this time we have progressed from the caviar and smoked salmon on to the couscous and lamb, and Barbara deems it time to widen our perspectives. It would be the first of two calls to order, on this occasion to introduce everyone to everyone, a party game rather than a necessity, I think, except in my case. Thumbnail sketches of each participant, edged devilishly with in-group barb, courted ripostes and laughter, but it was only when she came around the table and settled on me, mentioning the words ‘guest of honour’ that I realised for the first time that I was to be the star turn. I needn’t have worried; there was at least one other special guest in Joan Rivers and she more than made up for my sadly unimaginative response.

Barbara tells me that Joan is very ‘in’ with Prince Charles: ‘She greeted me with, “I’ve just come back from a painting trip . . . with Prince Charles.” A friend of hers, Robert Higdon, runs the Prince’s Trust. Joan is very involved with that, giving them money. So she was there with Charles and Camilla and the Forbses at some château somewhere. She always says, “Prince Charles likes me a lot; he always laughs at my jokes.” But Joan is actually a very ladylike creature when she is off the stage, where she can be a bit edgy sometimes. In real life she is very sweet and she loves me and Bob.’