Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "This Is a Call: The Life and Times of Dave Grohl"

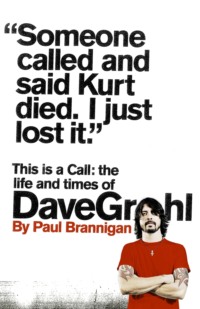

This is a Call: The Life and Times of Dave Grohl

By Paul Brannigan

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Foreword

Learn to fly

This is a call

Chaotic hardcore underage delinquents

Gods look down

Negative creep

Lounge act

Smells like teen spirit

I hate myself and I want to die

I’ll stick around

My poor brain

Disenchanted lullaby

Home

These days

Photographic Insert

Sources

Bibliography

Discography

Searchable Terms

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

Foreword

Dave Grohl has just slapped me across the face. It’s the early hours of 20 December 2005, and he and I are in a central London rock bar. Neither of us is meant to be here. Grohl is supposed to be in Ireland, resting up before his band Foo Fighters headline Dublin’s 8,000 capacity Point Depot; I had only dropped in to the Crobar for a swift pre-Christmas beer with colleagues. But sometimes, particularly for those of us with Irish blood, nights in bars take on a momentum all their own.

Surprised to see one another, Grohl and I caught up quickly: I had recently become a father and Dave’s wife Jordyn was five months pregnant, so babies and fatherhood dominated the early conversation. Then Grohl brought two trays laden with Jägermeister shots to our table and the evening began to get a little unhinged. Soon enough, all sensible conversation was abandoned. As the Crobar’s excellent jukebox spat the sounds of Metallica, Minor Threat, Venom, Black Flag, Slayer and the Sex Pistols into the night air Grohl and I started doing what men of a certain age do while listening to very loud rock music when very drunk – screaming out lyrics, thrusting clenched fists skywards and headbanging furiously. And it was in the midst of this unedifying frenzy that Dave Grohl asked me to give him a slap in the face, an ancient male bonding ritual that only those conversant in the hesher tradition will truly understand.

‘I can’t do that,’ I protested.

‘Why not?’ he asked.

‘Well, because … because … you’re Dave Grohl,’ I stammered.

‘Okay, I’ll go first then,’ said Grohl.

And with that, Foo Fighters’ grinning frontman unleashed a stinging right hander which almost lifted me off the sticky barroom floor. Out of politeness, then, it seemed only fair to hit him back …

I first met Dave Grohl in November 1997 in London. The afternoon was memorable for all the wrong reasons. I had been commissioned to interview Foo Fighters’ 28-year-old frontman for an end-of-year cover story for Kerrang! magazine, but, travelling back home following the interview, I discovered to my horror that our entire conversation had been wiped from the cassette in my dictaphone. Mortified, I begged Grohl’s long-standing PR man Anton Brookes to schedule another interview. Days later, I spoke with Grohl again backstage at London’s Brixton Academy: he had the manners and good grace not to laugh at my misfortune.

Over the next decade, I would run into the singer fairly regularly – at gigs, in TV studios, on the set of video shoots and in dingy rock clubs across the world; sometimes we would have business to conduct, at other times our contact was limited to the briefest of greetings. Relationships within the music industry are often conducted at such a level.

‘I would consider the two of us to be friends,’ Grohl told me as we had lunch at the Sunset Marquis hotel in West Hollywood in 2009 while conducting a lengthy interview for MOJO magazine. ‘This is the basis of our relationship, this working thing, but let’s go have a fucking beer, you know what I mean? But it would take a long time for you to really know me.’

In the eighteen months it has taken me to write this book, that sentence has entered my head one hundred times. In truth, everyone thinks they know Dave Grohl. In an age where social networking has made Marshall McLuhan’s 1960s vision of a global village a reality, where Twitter and Facebook and Tumblr and Flickr conspire to log and classify every waking moment, Grohl’s public profile has been distilled down to one simple epithet: he is, by common consent, ‘The Nicest Man in Rock’. But in effect this rather meaningless, reductive phrase has allowed the ‘real’ Dave Grohl to remain hidden in plain sight, unknown to all but his closest friends.

Based upon insights drawn from first-hand interviews with Grohl’s friends, peers and associates, and from my conversations with the man himself, this is my attempt to tell Dave Grohl’s story. It is an epic tale, documenting a journey which has taken Grohl from Washington DC’s scuzziest punk rock clubs to the White House and the world’s most imposing stadia. It’s a story which ties together strands from fifty years of rock ’n’ roll history, from Bob Dylan, The Beatles and Led Zeppelin through to Sonic Youth, Queens of the Stone Age and The Prodigy in a singular career, one which speaks volumes about both the evolution of the recording industry and the manner in which music soundtracks our lives. On a more basic level, it’s a story about family and a musical community which continues to inspire, empower and engage.

During the course of writing this book, I spoke to Dave Grohl both on and off-record, and he was kind enough to permit me to visit his family home in California during the making of Foo Fighters’ current album Wasting Light. The last time I talked with Dave was on 3 July 2011, minutes after his band performed in front of 65,000 people for a second consecutive evening at the National Bowl in Milton Keynes, England. That was a special night, a night for celebration, but also one which felt like the beginning of a whole new chapter for this most resolute of musicians. That future is unwritten; this is the story so far.

Paul Brannigan

London, July 2011

Learn to Fly

A big rock ’n’ roll moment for me was going to see AC/DC’s Let There Be Rock movie. That was the first time I heard music that made me want to break shit. That was maybe the first moment where I really felt like a fucking punk, like I just wanted to tear that movie theatre to shreds watching this rock ’n’ roll band …

Dave Grohl

In 1980, in a song named after their Los Angeles hometown, the punk band X sang of a female acquaintance who had lost her way, lost her innocence and lost her patience with the City of Angels, a friend desperate to flee the squalid, druggy Hollywood scene and unforgiving streets where ‘days change at night, change in an instant’. But even as Farrah Fawcett Minor was dying to get out, get out, one young punk on the East Coast was dreaming of heading in the opposite direction.

As a child, Dave Grohl had a recurring dream, one that stole into his head in the hours of darkness ‘a thousand fucking times’. In this dream, he was riding a tiny bike from his home in Springfield, Virginia to Los Angeles, cruising slowly along the side of the highway as cars whizzed past with horns blaring and tail pipes smoking. Generations of bored, restless suburban kids have harboured similar fantasies of escaping suffocating small-town life for the glister of Hollywood. Deep in the national psyche LA remains synonymous with freedom, opportunity and boundless glamour, and the city’s entertainment industries, both legal and less legal, have grown fat feasting upon the wide-eyed ingénues who spill daily from incoming Greyhound coaches and Amtrak trains, but young Grohl’s imagination was fired less by the shimmering promises of the Golden State than by the excitement of whatever swerves and undulations might have to be negotiated on his westward odyssey.

In September 2009 I had lunch with Foo Fighters’ frontman at West Hollywood’s chic Sunset Marquis hotel. As he picked at a Caesar salad, Grohl, modern rock’s most convincing renaissance man, described the early days of his life’s journey as being informed by a ‘sense of adventure’, of ‘not knowing what lay ahead’.

‘In that dream I had so far to go,’ he said, ‘and I was going so slow, but I was moving.’

Los Angeles is a city which holds memories both good and bad for Grohl. A decade ago he would tell anyone who’d listen that he hated this town, hated the Hollywood lifestyle, and hated pretty much everyone he met here:

‘It’s kinda funny for a while,’ he conceded, ‘then annoying, then depressing, finally it gets terrifying because you start wondering if these people are rubbing off on you. It’s like one giant frenzy of aspiration and lies.’

But now Los Angeles, or more specifically Encino, 15 miles northwest of Sunset Boulevard’s celebrity haunts, and a neighbourhood Grohl once defined as a place where ‘porn stars become grocery clerks and rock stars come to die’, is his home. Here, overlooking the San Fernando Valley, Dave Grohl literally has Los Angeles at his feet.

Grohl bought his house, a tasteful four-bedroom 1950s villa set on almost 4,000 square feet of prime Californian real estate, for $2.2 million in April 2003; four months later, surrounded by friends and family, he married MTV producer Jordyn Blum on the tennis court at the rear of the property. And it was here that Grohl elected to record Foo Fighters’ seventh studio album Wasting Light in autumn 2010, eschewing digital studio technology in favour of tracking to analogue tape, a process largely viewed as antiquated within the modern recording industry.

From the outset, it seemed like a curious move, verging on the perverse: Grohl has his very own state-of-the-art recording complex, Studio 606, in Northridge, California, not ten minutes’ drive from his home, and though his house in Encino also contains a compact home studio built around a 24-track mixing desk, the set-up is very much that of a family home, not some rock star bolthole. In contrast to houses in Los Angeles’ more fashionable zip codes, there are no high fences surrounding the Grohl residence, no signs warning of armed security guards patrolling the perimeters: a plaque on the left-hand side of the driveway simply reads The Grohls. When you step inside the front door there are no gold or platinum discs on the hallway walls, no framed magazine covers, no posed portraits with celebrity friends, nothing to signpost the road Dave Grohl has travelled to get here: instead there are family snapshots and brightly coloured crayon-drawn abstract artwork tacked to the walls, the work of artists-in-residence Violet Maye Grohl and Harper Willow Grohl, Dave and Jordyn’s young daughters.

In November 2010 I was invited to the Grohl family home to interview Foo Fighters about their work-in-progress. I arrived to find the man of the house in his garage, holding up scuffed album sleeves and fingerprint-smudged CD cases from his personal record collection to a webcam delivering images for a 24/7 live stream on Foo Fighters’ website. Among them were Bad Brains’ Rock for Light, Metallica’s Master of Puppets, AC/DC’s Back in Black, Thin Lizzy’s Live and Dangerous, Ted Nugent’s Cat Scratch Fever, Pixies’ Trompe Le Monde and Led Zeppelin’s Houses of the Holy, each album a strand of Grohl’s musical DNA, each one a part of the soundtrack of his life. Behind him, producer Butch Vig stood splicing two-inch analogue tape on a 24-track Studer A800 reel-to-reel tape machine. In the room next door, eighteen of Grohl’s guitars stood erect in flight cases, tuned and ready for use. In the adjoining garage, usually reserved for Grohl’s Harley Davidson motorcycles, Taylor Hawkins’s drum kit sat encircled by mic stands.

‘It gets fucking loud in there,’ said Grohl, closing the door with a smile.

Upstairs in the studio control room, band members Pat Smear, Chris Shiftlet, Nate Mendel and Hawkins sat sharing cartons of take-away food. Around them Grohl strode animated, enthusing about his belief that Wasting Light would be Foo Fighters’ definitive work. And as he spoke, his decision to record here began to make sense, indeed began to look inspired.

‘It only seemed like a good idea to do it here,’ Grohl insisted. ‘I wasn’t nervous about it at all. What we’re doing here is in some ways making sense of everything we’ve done for the last fifteen years.

‘It all came together as one big idea. Let’s work with Butch, but let’s not use computers, let’s only use tape. Let’s not do it at 606, let’s do it in my garage. And let’s make a movie that tells the history of the band as we’re making the new album, so that somehow it all makes sense together in the grand scheme of things. I feel like you can actually hear the whole process in the album.’

For Grohl, the notion of time, its passing, its deathless march and the value and importance of seizing precious moments, is central to Wasting Light. But later that night, as I played back the cassette recording of the day’s conversations, it struck me that the process unfolding in Encino was perhaps more personal than Dave Grohl would care to acknowledge explicitly: as he spoke of garage demos and life-changing albums, of collaborations with heroes and friends, of teenage desires and adult responsibilities, it seemed that in making Foo Fighters’ seventh album Dave Grohl was seeking not merely to define his band’s career, but also to make sense of his own life to date. And who could blame him? For his has been a journey more dramatic than that adolescent dreamer back in Virginia could ever have imagined.

Between 1880 and 1920 almost 24 million immigrants arrived in the United States, the majority of them from Southern and Eastern European nations. Pursuing his own dreams, Dave Grohl’s great-grandfather was among their number.

Born in Slovakia, then a part of the powerful Austro-Hungarian Empire, John Grohol was admitted to America in 1886, the same year in which the Statue of Liberty was erected on Bedloe’s Island in New York Harbor. Like the vast majority of Slovaks who boarded dangerously overcrowded, unsanitary steamer ships for the twelve-day voyage to America’s eastern seaboard, Grohol was an economic migrant: without a trade to his name when he arrived in the USA, he was drawn to the state of Pennsylvania by the promise of unskilled labour in the region’s coalfields and steel mills. The state was a popular destination for Slovak immigrants: when Grohol made his home in the small town of Houtzdale in Clearfield County, he was just one of approximately 250,000 Slovaks to put down roots within the borders of the Keystone State between 1880 and 1920. This influx of new labour engendered a certain amount of tension in the region.

Racist attitudes towards the settling Eastern European community were laid out in the bluntest terms by a report commissioned by the US Immigration Commission, published in 1911. Presented to Congress by the Republican Senator for Vermont, William P. Dillingham, Volume 16 of the Reports of the Immigration Commission: Immigrants in Industries dealt with studies into communities built around ‘Copper Mining and Smelting; Iron Ore Mining; Anthracite Coal Mining; [and] Oil Refining’ in Michigan, Minnesota and Pennsylvania, and concluded that white, American-born workers were being displaced by ‘the more recent settlers of the community’, referred to elsewhere in the report as ‘the ignorant foreigner’.

One excerpt of Dillingham’s report stated:

The social and moral deterioration of the community through the infusion of a large element of foreign blood may be described under the heads of the two principal sources of its evil effects: (a) The conditions due directly to the peculiarities of the foreign body itself; and (b) those which arise from the reactions upon each other of two non-homogeneous social elements – the native and the alien classes – when brought into close association. Among the effects under the first-named class may be enumerated the following:

A lowering of the average intelligence, restraint, sensitivity, orderliness, and efficiency of the community through the greater deficiency of the immigrants in all of these respects.

An increase of intemperance and the crime resulting from inebriety due to the drink habits of the immigrants.

An increase of sexual immorality due to the excess of males over females …

Baldly put, the ‘new immigrants’ were regarded as a dangerous breed of subhumans.

The Dillingham Commission concluded that immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe posed a significant threat to American society and should in the future be greatly reduced. These findings were used to justify a series of new laws in the 1920s which served to place restrictions on immigration, and which also served to place a veneer of legitimacy on increasingly hostile, often blatantly discriminatory employment practices towards foreign-born workers.

Faced with such widespread attitudes and beliefs, it’s understandable that when John Grohol and his wife Anna, herself a Slovakian immigrant, started their own family, their four sons – Joseph, John, Alois and Andrew – were encouraged to adopt the less obviously Slovakian, more Americanised surname Grohl in order to better assimilate into the prevailing culture.

Ethnic conflict was not, however, confined to the United States. Tensions were also running high in Europe, with questions of sovereignty, race and national self-determination causing division and toxic discord. The 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, by Yugoslav nationalist Gavrilo Princip acted as the catalyst for a breakdown in international diplomacy in the Balkans, a situation which ultimately led to the outbreak of the First World War.

By the time America entered the Great War in April 1917, the Grohol family themselves had crossed state lines and moved to Canton, Ohio, setting up home at 116 Rowland Avenue, in the north-east of the city.

Canton was a hard, working-class town, built around its steel mills, which had embarked upon massive recruitment drives required to accommodate the increased productivity needed for the war effort. As his second eldest boy, John Stephen, enlisted in the United States army, John Grohol senior took up a position as a hammerman in one such factory. During this period Canton’s population swelled significantly – the 1920 census recorded the town as being home to 90,000 residents, a leap of almost 40,000 from figures collated just a decade previously – but among this new influx of citizens were less savoury elements, attracted by the town’s increased prosperity.

By the mid 1920s Canton had acquired the unwanted nickname ‘Little Chicago’ in recognition of the growth of underworld gangs busying themselves with organised prostitution, bootlegging and gambling operations in the town’s newly established red-light districts. Suspicious of the local police force’s apparent unwillingness to crack down on such illicit activities, newspaper editor Donald Ring Mellet conducted his own investigations, exposing the collusion between gangsters and police in a series of searing articles published in the Canton Daily News. Mellet paid a high price for his crusading efforts: on 16 July 1926 the journalist was shot dead at his home in a cold-blooded execution which sent shockwaves through the local community. This was not the American Dream as John Grohol had envisaged it. It was time for his family to move on once more. They headed north-east, this time for Ohio’s industrial heartland.

Residents of Warren, Ohio refer to their hometown as ‘The Festival City’ in recognition of the various celebrations of heritage, culture and art held throughout the year for the local community. In the summer of 2009, one such event – the inaugural Music Is Art festival – attracted thousands of music fans to the city’s downtown Courthouse Square. On display from 26 July to the first day of August were no less than 48 acts, a rich variety of musicians and artists. But on the afternoon of 1 August there was little debate as to the festival’s headline attraction.

‘Is this the most beautiful day of your life?’ Dave Grohl asked the crowd gathered on the lawn of the Trumbull County Courthouse as he was presented with the key to the city on the Music Is Art stage. ‘Because it is mine.’

‘I was born here, at the hospital just down the street, over at Trumbull Memorial,’ Grohl continued. ‘Most of my family is from the Niles and the Youngstown and the Warren area: my mother went to Boardman High School, my father went to the Academy …’

Standing alongside Grohl’s father James and mother Virginia, Warren Police Sergeant Joe O’Grady felt a surge of pride as he watched the city’s most famous son address his audience. Dave Grohl had perfected the art of speaking to a large group as if he were having an intimate one-to-one conversation with a close friend, and the crowd listened rapt as he spoke in his easy-going, everyman manner of his family’s history in Ohio: about his paternal grandfather Alois Grohl’s work at Republic Steel in Youngstown, his maternal grandfather John Hanlon’s employment as a civil engineer on the Mosquito Dam building project in the 1940s, and his own pride in hailing from the town.

The Music Is Art festival was Sgt Joe O’Grady’s brainchild, and it was his idea too to lobby the city council to rename a downtown street in Dave Grohl’s honour. This tribute, he argued, would bolster civic pride, and in saluting Grohl’s musical achievements the city elders would send an inspirational message to the youth of Warren about fulfilling their own potential. In September 2008 Warren City Council passed O’Grady’s resolution, and Market Street Alley was officially renamed David Grohl Alley.

On the morning of the dedication ceremony, Joe O’Grady walked Dave Grohl through downtown Warren to meet with one young man whose story had become entwined with the police officer’s own vision and passion for the project.

Throughout the summer of 2009, Jacob Robinson, an eighteen-year-old skater and aspiring rapper, had worked long days in David Grohl Alley, sweeping the asphalt street and removing weeds and leaves from every crack in the bordering walls, so that artists from the Trumbull Art Gallery could paint murals along its length. Initially these chores were undertaken as part of a community service programme, after a fracas with a local police officer who’d apprehended him for skateboarding on a public street (a misdemeanour under the city’s penal code).

But as O’Grady explained to Grohl, as Robinson’s involvement in the project deepened so too did the teenager’s sense of self-esteem. In Robinson’s story Grohl heard an echo of his own formative years: himself a self-confessed ‘little vandal’ during adolescence, he saw in Robinson another creative, frustrated, headstrong young man in need of direction. In a log cabin adjacent to Monument Park he spoke with the young skater as he signed his skate deck, telling him, ‘You and I are a lot alike.’

‘When I was your age, I was into skateboarding and I was into music,’ said Grohl. ‘I did my best to be myself and stay out of trouble …’

The sentence was left hanging, but its subtext was clear enough to both Robinson and the listening Joe O’Grady. This was precisely the kind of non-judgemental pep talk to which Robinson could connect, the kind of positive message the progressive policeman would himself repeat in the months and years ahead to other kids who felt both disillusioned and disenfranchised growing up in Warren.

‘A kid who’s fifteen years old doesn’t feel there’s hope,’ O’Grady told a local entertainment website. ‘But just because you’re born here doesn’t mean you’re a nobody.’

David Eric Grohl was born on 14 January 1969 at Trumbull Memorial Hospital in Warren, just one mile from the street that now bears his name. He was James and Virginia Grohl’s second child, and a brother for their daughter Lisa, then still a month shy of her third birthday. Speaking with Nirvana biographer Michael Azerrad in 1993, Grohl described his parents as being positioned ‘pretty much at other ends of the spectrum’: in his eyes, his father was ‘a real conservative, neat, Washington DC kind of man’, his mother ‘a liberal, free-thinking, creative’ type, but in the early years of the couple’s relationship their shared passions evidently eclipsed such ideological divisions.

Virginia Jean Hanlon met James Harper Grohl while working in community theatre in Trumbull County. She was a striking, smart and sassy trainee teacher, he a quick-witted, charming and confident young journalist. Grohl was a classically trained flautist – nothing less than a ‘child prodigy’, according to his son – and a keen jazz buff; Hanlon sang with high school friends in an a cappella vocal group named the Three Belles. The pair also shared a love of poetry and literature, particularly the provocative counter-culture writings of Beat Generation authors Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. In later years, in the company of his son’s more artistic, liberal-minded friends, James Grohl was fond of wheeling out an anecdote about Ginsberg (unsuccessfully) hitting on him when the pair moved in the same bohemian circles, a pointed reminder to his son that he wasn’t always such a strait-laced square.

At the time of his son’s birth, James Grohl was a journalist for the Scripps Howard news agency, a division of the multi-platform communications empire built up by the tough-talking Illinois-born media mogul Edward Willis Scripps. With a culture encouraging independent thinking, instincts for social reform and a healthy disrespect for authority, it was a fecund environment for any ambitious young journalist. For James Grohl, this avowed policy of fearless, scrupulous news-gathering was never more important than when he was called upon to cover the student protests at Kent State University in nearby Kent, Ohio in May 1970.

Founded in 1910 as a teacher training college, Kent State was officially accorded university status in 1935; then, as now, the college prided itself upon a commitment to ‘excellence in action’. By 1970 the student body, which included future Pretenders singer Chrissie Hynde, then an eighteen-year-old art student, numbered 21,000 across all programmes. That student body had become enraged when US President Richard Nixon, a man elected two years earlier on a pledge to end the war in Vietnam, announced on 30 April 1970 that US combat forces had invaded neighbouring Cambodia, an act widely interpreted as an escalation of the conflict.

When sporadic rioting broke out in the city in the wake of an anti-war demonstration on the university campus on 1 May, Mayor Leroy Satrom declared a state of emergency, and Ohio Governor James Allen Rhodes sent the National Guard to Kent to quell the disturbances and restore order.

On 4 May, when 2,000 protestors gathered on the university commons for another scheduled protest, they were ordered to disperse. When it became clear that the protestors were not prepared to comply with this injunction, the Guardsmen fired first tear gas, then live ammunition, into their midst. Four students were killed, and nine more injured.

Dubbed ‘the Kent State Massacre’ by the media, the killings galvanised the American anti-war movement. In the wake of the shootings, angry demonstrations were held on college campuses nationwide, and on 9 May an estimated 100,000 people converged upon Washington DC to protest against the Vietnam War and the horrifying events in Ohio. In response, the Nixon administration called upon the military to defend government offices, as the President was secreted from the District of Columbia to Camp David in Maryland for his own safety. White House staffers viewed the tense stand-off with mounting panic: upon seeing armed soldiers in the basement of the executive offices, one Nixon aide later commented, ‘You’re thinking “This can’t be the United States of America. This is not the greatest free democracy in the world. This is a nation at war with itself.”’

James Grohl’s dispatches from Ohio marked him out as a rising star within the Scripps Howard news service. In 1972, while working in Columbus, Ohio, he was asked to consider a move to Washington DC, the nation’s capital and political nerve centre, to develop his career further. For Grohl, the timing was perfect. This was the age of the crusading journalist, with Washington Post reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward being hailed as American heroes for their incisive and explosive investigations into a seemingly trivial burglary at the Watergate Hotel on 17 June 1972, which exposed a botched attempt to bug the offices of the Democratic National Committee offices and uncovered a paper trail all the way to the White House, leading to the resignation of ‘Tricky Dickie’ Nixon on 8 August 1974. What upwardly mobile young reporter wouldn’t wish to join the pair on the frontline in their tenacious pursuit of the truth? It was an opportunity Grohl accepted without reservation.

Like so many other transplants to the DC metropolitan area, he chose to relocate his family not in the District of Columbia itself, but in the outlying suburbs. Springfield, Virginia lay six miles down the I-95, just inside the Capital Beltway, and like the neighbouring towns of Arlington, Annandale and Alexandria it was a popular destination for commuters working in the city or at the nearby Pentagon offices. As with other Northern Virginian towns, it had a transient population, with the shifting dynamics of working on Capitol Hill leading many families to relocate after four or five years in the area. Despite this, residents worked hard to foster and maintain a strong community spirit.

At the dawn of the 1970s the Grohls’ new hometown was a location suited to the patronising sobriquet ‘white-bread’. But, befitting a town ‘15 minutes from chicken farmers, and 15 minutes from the White House’, as Dave Grohl would later describe it, Springfield, VA also had a more schizophrenic character. Here, urbane, moneyed politicos – those ‘fortunate sons’ eviscerated in song by Creedence Clearwater Revival – shared street space with blue-collar Southerners with gun racks on their pickup trucks and Skynyrd and Zeppelin blasting from their Camaros and Ford Mustangs.