Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Money in the Morgue"

Copyright

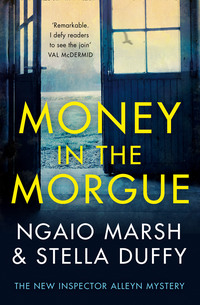

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by Collins Crime Club 2018

Copyright © Stella Duffy and the Estate of Ngaio Marsh 2018

Cover design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photographs © Ingrid Michel/Arcangel Images and Shutterstock.com (front), Simon Bradfield/Getty images (back)

Stella Duffy and Ngaio Marsh assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008207106

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780008207120

Version: 2019-01-07

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Cast of Characters

Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Acknowledgements and Author’s Note

About the Authors

The Inspector Alleyn Mysteries

Also by Stella Duffy

About the Publisher

CAST OF CHARACTERS

| Mr Glossop | A payroll delivery clerk |

| Matron Ashdown | The Matron of Mount Seager Hospital |

| Sister Comfort | A Sister at Mount Seager Hospital |

| Father O’Sullivan | The local vicar |

| Sarah Warne | The hospital Transport Driver |

| Sydney Brown | The grandson of old Mr Brown |

| Rosamund Farquharson | A hospital clerk |

| Private Bob Pawcett | A convalescent soldier |

| Corporal Cuthbert Brayling | A convalescent soldier |

| Private Maurice Sanders | A convalescent soldier |

| Dr Luke Hughes | Doctor at Mount Seager Hospital |

| Roderick Alleyn | Chief Detective Inspector, CID |

| Old Mr Brown | A dying man |

| Will Kelly | The night porter |

| Sergeant Bix | A Sergeant in the New Zealand Army |

| Duncan Blaikie | A local farmer |

| Various patients—convalescent soldiers and civilians | |

| Several night nurses, nurse aides and VADs |

Map

Mount Seager Hospital and the surrounding area

CHAPTER ONE

At about eight o’clock on a disarmingly still midsummer evening, Mr Glossop telephoned from the Transport Office at Mount Seager Hospital to his headquarters twenty miles away across the plains. He made angry jabs with his blunt forefinger at the dial—and to its faint responsive tinkling an invisible curtain rose upon a series of events that were to be confined within the dark hours of that short summer night, bounded between dusk and dawn. So closely did these events follow the arbitrary design of a play that the temptation to represent Mr Glossop as an overture cannot be withstood.

The hospital, now almost settling down for the night, had assumed an air of enclosed and hushed activity. Lights appeared behind open windows and from the yard that ran between the hospital offices and the wards one could see the figures of nurses on night duty moving quietly about their business. Mingled with the click of the telephone dial was the sound of distant tranquil voices and, from the far end of the yard, the very occasional strains of music from a radio in the new army buildings.

The window of the Records Office stood open. Through it one looked across the yard to Wards 2 and 3, now renamed Civilian 2 and Civilian 3 since the military had taken over Wards 4–6 and remade them as Military 1, 2, and 3. Those in Military 3 were still very ill, those in Military 1, their quarantine and spirits up, were well into the restlessly bored stage of their recuperation. Each ward had a covered porch, and a short verandah at the rear linking it to the next ward. Before each verandah stood a rich barrier of climbing roses. The brief New Zealand twilight was not quite at an end but already the spendthrift fragrance of the roses approached its nightly zenith. The setting, in spite of itself, was romantic. Mr Glossop, however, was not conscious of romance. He was cross and anxious and when he spoke into the telephone his voice held overtones of resentment.

‘Glossop speaking,’ he said. ‘I’m still at Mount Seager Hospital. If I’ve said it once I’ve said it a hundred times, they ought to do something about that van.’ He paused. A Lilliputian voice reaching him from a small town twenty miles away quacked industriously in the receiver. ‘I know, I know,’ said Mr Glossop resentfully, ‘and it’s my digestion that’s had to take it. Here I am with the pay-box till Gawd knows when and I don’t like it. I said I don’t like it. It’s OK, go and tell him. Go and tell the whole bloody Board. I want to know what I’m meant to do now.’

A footfall, firm and crisp, sounded on the asphalt yard. In a moment the stream of light from the office door was intercepted. The old wooden steps gave the slightest creak and in the doorway stood a short compact woman dressed in white with a veil on her head and a scarlet cape about her shoulders. Mr Glossop made restless movements with his legs and changed the colour of his voice. He smiled in a deprecating manner at the newcomer and he addressed himself to the telephone. ‘That’s right,’ he said with false heartiness. ‘Still we mustn’t grumble. Er—Matron suggests I get a tow down with the morning bus … Transport Driver … No, it’s—it’s,’ Mr Glossop swallowed, ‘it’s a lady,’ he said. The Lilliputian voice spoke at some length. ‘Well, we hope so,’ said Mr Glossop with a nervous laugh.

‘You will be quite safe, Mr Glossop,’ the woman in the doorway said. ‘Miss Warne is an experienced driver.’

Mr Glossop nodded and smirked. ‘An experienced driver,’ he echoed, ‘Matron says, an experienced driver.’

The telephone uttered a metallic enquiry. ‘How about the pay-box?’ it asked sharply.

Mr Glossop lowered his voice. ‘I’ve paid out, here,’ he said cautiously. ‘Nowhere else. I should have been at the end of the rounds by now. Tonight, I’ll watch it,’ he added fretfully.

‘Tell him,’ the Matron said tranquilly, ‘that I shall lock it in my safe.’ She came into the office and sat at one of the two desks. She was a stocky woman with watchful eyes and a compassionate mouth.

Mr Glossop finished his conversation in a hurry, hung up the receiver and got to his feet. His tremendous circumference rose above the edge of the table and was rotated to face the Matron. He passed his hand over his face, glanced at it and pulled out a handkerchief. ‘Warm,’ he said.

‘Very,’ said the Matron. ‘Nurse!’

‘Yes, Matron?’ A very small figure in a blue uniform and white cap rose from behind the second desk where she had been studiously avoiding overhearing Mr Glossop’s telephone call.

‘Hasn’t Miss Farquharson got back yet?’

‘No, Matron.’

‘Then I’m afraid you must stay on duty until either she or Miss Warne returns. I wish to speak to Miss Farquharson when she comes in.’

‘Yes, Matron,’ said the small nurse in a very small voice.

‘I’m extremely annoyed with her. And now I want you to telephone Mr Brown’s grandson. Mr Sydney Brown. The number’s on the desk there. Mr Brown has asked for him again. He could come out on the next bus but it would be quicker if he used his own car, and possibly safer as there’s every chance we’ll have a storm to break this weather before the evening’s out. Tell him, as plainly as you can, that his grandfather is adamant he sees him, and time is not on his side. I really do think young Mr Brown ought to have visited before now.’

‘Yes, Matron.’

‘Somebody very sick?’ asked Mr Glossop, opening his eyes wide and drawing down the corners of his mouth.

‘Possibly dying. It must be said, we have expected this for weeks and the gentleman seems to rally every time. It cannot go on though, and it’s very important to the old man that he sees his grandson,’ said the Matron crisply before turning back to the nurse and adding, ‘Father O’Sullivan is cycling over from visiting a local parishioner to sit with old Mr Brown, make sure he finds me as soon as he arrives, will you? He arranged this visit a few days ago, but I’d like to update him on the old gentleman’s condition first. Now come along with me, Mr Glossop, we’d better lock up that money of yours. Is there much?’

‘It’s all in the box,’ he said, and lifted a great japanned case from the floor. ‘Should have been empty by now, you know. Four more staffs are paid off after I leave here. As it is—’

‘Mount Seager Hospital speaking,’ said the little nurse into the telephone. ‘I have another message for Mr Sydney Brown, please.’

‘Just on a thousand,’ said Mr Glossop behind his hand.

‘God bless my soul, of course I understood you were carrying payrolls for several locations, but that is an enormous responsibility,’ rejoined the Matron.

‘Exactly what I’m always telling Central Office,’ Mr Glossop replied, glad to have the Matron’s understanding.

They went out to the steps. The little nurse’s voice followed them: ‘Yes, I’m afraid so. Not long, Matron says … Yes, he’s asked for you again.’

‘Just along here,’ said the Matron.

Mr Glossop followed her down the yard that formed a wide lane, flanked on one side by offices, each with its distinguishing notice, and on the other by the wards set at intervals in sun-scorched plots, their utility gloriously interspersed by the roses which so recklessly floundered over the barb wire fences in front of the connecting verandahs. From the covered porch of each ward came a glow of diffused light. The asphalt lane was striped with warmth. The usual tang of mountain air was missing in the sultry evening and the subdued reek of hospital disinfectants seemed particularly strong to Glossop’s sensitive nose.

As they drew level with Military 1, the porch door slammed open and in a moment a heavy figure in nurses’ uniform flounced into the yard. A chorus of raucous voices yelled in unison: ‘And don’t let it occur again.’

The nurse advanced upon Mr Glossop and the Matron. Her face was in shadow, but her glasses caught a gleam of reflected light. A badge of office which she wore on the bosom of her uniform was agitated and her veil quivered. She took two or three short steps and stopped, clasping her hands behind her back. In the ward the raucous voices continued in a falsetto chorus: ‘Temperatures normal! Pulses normal! Bowels moved! Aren’t we lucky?’

‘Matron!’ said the stout nurse in an agitated whisper. ‘May I speak to you?’

‘Yes, Sister Comfort, what is it?’

‘Those men—in there—it’s disgraceful. This entire notion of allowing them leeway now that they’re recuperating—’

‘Is a well-proven method for speeding up recovery. Rest and silence, Sister Comfort, is the old-fashioned way, the men benefit tremendously when we give them something to think about that is neither their illness nor their return to the war. Distraction is a nurse’s best ally. However, I do agree there’s far too much noise,’ the Matron nodded. ‘Will you excuse us, Mr Glossop?’

Mr Glossop moved away.

‘Now, Sister,’ said Matron.

‘It’s disgraceful,’ Sister Comfort repeated in a grumbling voice. ‘I’ve never been treated like it in my life before. The impertinence!’

‘What are they up to?’

‘Temperatures normal! Pulses normal! Bowels moved! Aren’t we lucky?’

‘Just because I happened to pass the remark when I’d been round the ward,’ Sister Comfort said breathlessly. ‘They turn everything I say into ribaldry. There’s no other word. I can’t speak without them calling after me like parrots. And another thing, three of them are still out.’

‘Which three, Sister?’

‘Sanders, Pawcett and Brayling, of course. They had leave to go as far as the bench at the main gate.’ Sister Comfort’s voice trailed away on a note of nervousness. There was a brief silence broken only by the Matron.

‘I thought I had made it quite clear,’ Matron said, ‘that they were all to be in bed by seven. Distraction by day, rest by night, you know the rules.’

‘But, I can’t help it. They won’t obey orders,’ complained Sister Comfort.

‘They’re getting better,’ Matron said, ‘and they’re bored.’

‘But how can I keep order? Almost ninety soldiers and hardly any trained nurses. The VADs are not to be trusted. I know, Matron. I’ve seen what goes on. It’s disgusting.’

‘Nurse! Come over here and hold my hand,’ sang the patients.

‘There!’ cried Sister Comfort. ‘And the girls go and do it. I’ve seen them. And not only that—that Farquharson girl in the Records Office—’

‘Nursey, Nursey, going to get worsey.’

‘Come and hold my hand.’

‘Where is Sergeant Bix?’ asked the Matron.

‘Several of the men are due to be discharged this weekend coming and he has a huge amount of paperwork to get through before he can let them go. He’s not much use anyway, Matron, in my opinion, far too warm with the men. They’re the worst lot of patients we’ve ever had. Never in my life have I been spoken to—’

‘I’ll report you to Matron,’ said an isolated falsetto. ‘Call yourselves gentlemen? Well!’

‘Did you hear that?’ Sister Comfort demanded. ‘Did you hear it?’

‘I heard,’ said Matron grimly. The chorus was renewed. She folded her hands lightly at her waist and with an air of composure walked through the porch doors into the ward. The chorus faded away in three seconds. The isolated voice bawled a final line and died out in a note of exquisite embarrassment. Mr Glossop, who had hung off and on in the doorway to Matron’s office, approached Sister Comfort.

‘She’s knocked them,’ he said. ‘She’s a corker, isn’t she?’ He waited for a reply and getting none added with an air of roguishness: ‘It’s a wonder she hasn’t made some lucky chap very happy, isn’t it?’

With a brusque movement Sister Comfort twisted her head so that the light from Matron’s office fell across her face. Mr Glossop took a step backwards and then checked as if in surprise at himself.

‘What is the matter?’ asked Sister Comfort harshly.

‘Nothing, I’m sure,’ Mr Glossop stammered. ‘Nothing at all. You looked a little pale, that’s all.’

‘I’m tired out. The work in that ward’s enough to kill you. It’s the lack of discipline. They want military police.’

‘Matron’s fixed them for you,’ said Mr Glossop, and recovering from whatever effect he had experienced he added in his fat and unctuous voice: ‘Yes, she’s a beautiful woman, you know. Not appreciated.’

‘I appreciate her,’ said Sister Comfort loudly. ‘We’re very friendly, you know. Of course, in public we have to be formal—Matron and Sister and all that—but away from here she’s quite different. Quite different.’

‘You’re privileged,’ Mr Glossop murmured and cleared his throat.

‘Well, I think I am,’ Sister Comfort agreed, more amiably.

The Matron returned and with a brisk nod to Mr Glossop led the way into her office. After they had left her, Sister Comfort stood stock-still in the yard, her head bent down as if she listened attentively to some distant, almost inaudible sound. Presently, however, she turned into Military I but went no further than the porch; standing there in a dark corner and looking out obliquely across the yard at the Records Office. A few moments later a VAD scurried out of the ward. She experienced what she afterwards described as one hell of a jolt when she saw Sister Comfort’s long heavy-jowled face staring at her out of the shadow.

‘Doing the odd spot of snooping, that’s what she was up to, the old stinker,’ said the VAD. ‘She’s got a mind like a sink. And anyway,’ the VAD added complacently, ‘my fiancé’s in the air force.’

CHAPTER TWO

Matron took a key from her pocket and opened the safe.

Mr Glossop hesitated and she looked to him, ‘Yes?’

‘Are you quite sure you don’t have a single spare tyre out here, Matron?’

‘As I told you earlier, Mr Glossop, on both occasions that you asked, we do not. There are two spare tyres for the transport bus, that’s all. You know as well as I do that the bus is far bigger than your van, the tyres simply won’t fit. We’ve all had to make sacrifices for the war, up-to-the-minute repairs and plenty of extras in stock being just two of them.’

‘If you say so,’ he grumbled.

She looked at Glossop’s pay-box, sizing it up with a practised eye. ‘I’m afraid that great case of yours is too big,’ she said. ‘Try.’

Mr Glossop approached the japanned box to the safe. It was at least three inches too long.

‘Oh, Lord!’ he said. ‘Things have been like that with me all day.’

‘We shall have to find something else, that’s all.’

‘It’ll be all right. I won’t let it out of my sight, Matron. You bet I won’t.’

‘It’ll be out of your sight when you’re asleep, Mr Glossop.’

‘I won’t—’

Matron shook her head. ‘No. I can’t take the responsibility. We’ll give you a shake-down in the anteroom to the Surgery. I don’t expect you’ll be disturbed, but we can’t have the door locked, our medicines are stored in there and I can’t guarantee something won’t be needed in the night. The money’s done up in separate lots, isn’t it?’

‘It is, yes. I’ve got it down to a system. Standardized rates of pay, you know. I could lay my hand on anybody’s pay with my eyes shut. Each lot in a separate envelope. My system.’

‘In that case,’ said Matron briskly, ‘a large canvas bag will do nicely.’

She took one, folded neatly, from the back of the safe. ‘There you are. I’ll get you to put it in that and you’d better watch me lock it up.’

With an air of sulky resignation, Mr Glossop emptied one after another of the many compartments in his japanned box, snapping rubber bands round each group of envelopes before he stowed them in the bag. The Matron watched him, controlling any impatience that may have been aroused by the slow coarse movements of his hands. In the last and largest compartment lay a wad of pound notes held down by a metal clip.

‘I haven’t made these up yet,’ Mr Glossop said. ‘Ran out of envelopes.’

‘You’d better count them, hadn’t you?’

‘There’s a hundred, Matron, and five pounds in coins.’ He wetted his thumb disagreeably and flipped the notes over.

‘Dirty things,’ said the Matron unexpectedly.

‘They look lovely to me,’ Mr Glossop rejoined and gave a stuttering laugh.

He fastened the notes, dropped them in the bag and shovelled the coins after them. Matron tied the neck of the bag with a piece of string from her desk. ‘Wait a moment,’ she said. ‘There’s a stick of sealing-wax in the top right-hand drawer. Will you give it to me?’

‘You are particular,’ sighed Mr Glossop.

‘I prefer to be business-like. Have you a match?’

He gave her his box of matches and whistled between his teeth while she melted the sealing-wax and sealed the knot. ‘There!’ she said. ‘Now put it in the safe, if you please.’

Mr Glossop with difficulty compressed himself into a squatting posture before the safe. The light from the office lamp glistened upon his tight greasy curls and along the rolls of fat at the back of his neck and the bulging surface of his shoulders and arms. As he pushed the bag into the lower half of the safe he might have been a votary of some monetary god. Grunting slightly he slammed the door. Matron, with sharp bird-like movements, locked the safe and returned the key to her pocket. Mr Glossop struggled to his feet. ‘Now we needn’t worry ourselves,’ said Matron.

As she turned to leave, the little nurse from the Records Office appeared in the doorway. ‘Yes?’ Matron said. ‘Do you want me?’

‘Father O’Sullivan has come, Matron.’

Beyond the nurse stood a priest with a nakedly pink face and combed-back silver hair. He carried a small case and appeared impatient to see the Matron.

‘Excuse me, Mr Glossop, this is quite urgent, you know. I’ll send someone to fetch you to the Surgery anteroom,’ Matron said, and folding her hands at her waist walked out into the yard leaving Mr Glossop wiping his brow at the exertion he had just endured. He heard their voices die away as they moved off in the direction of Mr Brown’s private room.

‘… not long …’

‘… Ah … such a time … Is he …?’

‘… Very. Failing rapidly, but then he does keep rallying. It can’t possibly go on, of course. I’m not one to believe in miracles, although with the storm …’

The telephone in the Records Office pealed and the little nurse hurried back to answer it. To Mr Glossop her voice sounded like an echo: ‘… Mr Brown’s condition is very low,’ she was saying. ‘Yes, I’m afraid so … failing rapidly.’

Mr Glossop gazed vacantly across the yard at Military 1. His attention was arrested by something white that shifted in the porch entrance. He moved a little closer and then, since he was of a curious disposition and extremely short-sighted, several paces closer still. He was profoundly disconcerted to find himself staring up into Sister Comfort’s rimless spectacles.

‘Beg pardon, I’m sure,’ he stammered. ‘I didn’t know—getting dark, isn’t it? My mistake!’

‘Not at all,’ said Sister Comfort. ‘I could see you quite clearly. Good night.’

She stalked off, down the steps and along the yard, no doubt to harangue yet another benighted soldier, and Mr Glossop turned away with elephantine airiness.

‘Now what the hell,’ he wondered, ‘is that old cow up to?’

While Matron took Father O’Sullivan to minister to Mr Brown, Mr Glossop spent the next twenty minutes fidgeting and worrying in her office. He sat first in the chair opposite Matron’s desk, a lower chair than the one behind her desk, ideal for chastising foolhardy young nurses and miscreant soldiers, he assumed. He loosened his tie still further and rolled up the sleeves of his creased shirt. ‘Too damn hot by half,’ he thought, hoping Matron was right and the storm that had been threatening for days would finally make its way over the mountains tonight, clearing the air. ‘Not too wet though,’ he added to his wishes, ‘that damn bridge is worrisome enough, without the river rising as well.’ The chair creaking beneath his weight, he struggled to his feet and paced several times around Matron’s office. With effort, he bent down and tried the handle on the safe, reassuring himself that it was secure. He looked outside again, across to the row of wards and along the collection of offices hoping that Matron might be on her way back. He wanted someone to sort him out with that cot for the night, he wanted to get some sleep, and above all, he wanted to be on his way with his stack of cash, far too much money to be sitting way the hell out here, locked safe or no.

Wiping his brow and muttering dire imprecations against the weather, the Central Office, the roads and the general state of the nation in wartime, he sat down again, this time in Matron’s own chair. Her desk was covered in papers and he absent-mindedly flicked through them, misplacing the carefully-ordered typed pages of accounts and the hand-written notes.

He shook himself when he realized what he’d done, he’d hate to get in Matron’s bad books and he replaced the sheets carefully one on top of the other, grumbling to himself, ‘If I don’t get away from here at the crack of dawn there’ll be hell to pay, four more rounds to do. Four more and all of them to be paid before Christmas Day with the shops closing up soon enough and turkeys and stuffing and whatnot to cross off the lists. Hell to pay. None of it down to me, not a bit. I told them that old banger had no more in her. If I said it once, I said it a dozen times. I need a new van and hang the expense. Well, now they know the cost.’

Matron checked her watch as she returned to her office. A lovely silver watch, held on an elegant bar, it was given to her by a young man she’d known long ago. He had shyly offered it up just before he left for the last war, the one they had promised would end them all. They had been wrong and the young man had not returned. Not a day passed that she didn’t think of him, and not in a foolish way either, she admitted to herself, standing at the door to her office looking at the dozing irritant that was Mr Glossop, seated in her own chair. With a start, she noticed the papers on her desk had been moved, she crossed to the desk and, making no attempt to keep quiet for the sleeping interloper, she gathered the papers together, settling them once more with a satisfying thump.

‘Well, there we are,’ Glossop woke with a start, pretending he had only closed his eyes for a short while. ‘And how’s it with—you know, the fellow who’s—’

‘Dying?’

‘Yes, yes, that’s the—and the priest chap?’

‘Father O’Sullivan is with him now.’

‘Oh I see,’ Mr Glossop said disapprovingly, ‘All the Catholic doings, smells and bells and that carry on, is it?’

‘Not at all, Father O’Sullivan is an Anglican priest,’ Matron replied, attempting to squash his interest with the look that had her young nurses quaking and, to her chagrin, appeared to further encourage Mr Glossop.

‘Right you are, Matron, I’m sure you’ll tell me when I’m over-stepping bounds. I like a woman who knows her own business.’

Matron decided to ignore him. ‘It’s just gone eight-thirty, Mr Brown’s grandson is coming in on the nine o’clock transport. I hope he makes it in time. You’ll have to excuse me now, Mr Glossop, I’ve work to do.’

Glossop looked at the desk in front of him and realized that the papers he’d been fiddling with had been tidied out of his reach and that he himself was in Matron’s seat.

‘Yes, yes of course. You don’t want a spot of company? Someone to help you go through all those figures? Tricky stuff, numbers, and I’ve a good eye for accuracy, that’s why they gave me the job, of course. You’ve got to have a trusted man on the pay round.’

‘Thank you, but no,’ she cut him off. ‘If you head next door to the Records Office, the young nurse there will take care of you. She knows where the cots are kept and where you’re to sleep and I dare say she’ll be happy to show you to the kitchen. You’ll have to fend for yourself, mind you, our kitchen staff are daily and they left on the last transport back to town. Goodnight, Mr Glossop.’

Knowing himself dismissed, Glossop reluctantly left Matron’s office and went out into the darkening night. And it was still too damn hot by half.