Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

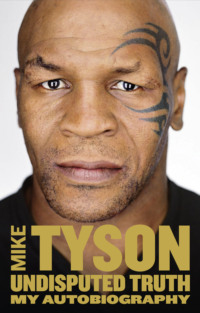

Buch lesen: "Undisputed Truth: My Autobiography"

Title Page

Dedication

PROLOGUE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

EPILOGUE

POSTSCRIPT TO THE EPILOGUE

A NOTE ON LEXICON

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

PHOTO CREDITS

PICTURE SECTION

Copyright

About the Publisher

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO ALL THE OUTCASTS –

EVERYONE WHO HAS EVER BEEN MESMERIZED,

MARGINALIZED, TRANQUILIZED, BEATEN DOWN,

AND GOTTEN THE WRONG END OF THE STICK.

AND INCAPABLE OF RECEIVING LOVE.

I spent most of the six weeks between my conviction for rape and sentencing traveling around the country romancing all of my various girlfriends. It was my way of saying good-bye to them. And when I wasn’t with them, I was fending off all the women who propositioned me. Everywhere I’d go, there were some women who would come up to me and say, “Come on, I’m not going to say that you raped me. You can come with me. I’ll let you film it.” I later realized that that was their way of saying “We believe you didn’t do it.” But I didn’t take it that way. I’d strike back indignantly with a rude response. Although they were saying what they said out of support, I was in too much pain to realize it. I was an ignorant, mad, bitter guy who had a lot of growing up to do.

But some of my anger was understandable. I was a twenty-five-year-old kid facing sixty years in jail.

My promoter, Don King, had kept assuring me that I would walk from these charges. He had hired Vince Fuller, the best lawyer that a million-dollar fee could buy. But I knew from the start that I was in trouble. I wasn’t being tried in New York or Los Angeles; we were in Indianapolis, Indiana, historically one of the strongholds of the Ku Klux Klan. My judge, Patricia Gifford, was a former sex crimes prosecutor and was known as “the Hanging Judge.” I had been found guilty by a jury of my “peers,” two of whom were black. Another black jury member had been excused by the judge after a fire in the hotel where the jurors were staying.

But in my mind, I had no peers. I was the youngest heavyweight champion in the history of boxing. I was a titan, the reincarnation of Alexander the Great. My style was impetuous, my defenses were impregnable, and I was ferocious. It’s amazing how a low self-esteem and a huge ego can give you delusions of grandeur. But after the trial, this god among men had to get his black ass back in court for his sentencing.

But first I tried some divine intervention. Calvin, my close friend from Chicago, told me about some hoodoo woman who could cast a spell to keep me out of jail.

“You piss in a jar, then put five hundred-dollar bills in there, then put the jar under your bed for three days and then bring it to her and she’ll pray over it for you,” Calvin told me.

“So the clairvoyant broad is gonna take the pissy pile of hundreds out of the jar, rinse them off, and then go shopping. If somebody gave you a hundred-dollar bill they pissed on, would you care?” I asked Calvin. I had a reputation for throwing around money but that was too much even for me.

Then some friends tried to set me up with a voodoo priest. But they brought around this guy who had a suit on. The guy didn’t even look like a drugstore voodoo guy. This asshole needed to be in the swamp; he needed to have on a dashiki. I knew that guy had nothing. He didn’t even have a ceremony planned. He just wrote some shit on a piece of paper and tried to sell me on some bullshit I didn’t do. He wanted me to wash in some weird oil and pray and drink some special water. But I was drinking goddamn Hennessy. I wasn’t going to water down my Hennessy.

So I settled on getting a Santeria priest to do some witch doctor shit. We went to the courthouse one night with a pigeon and an egg. I dropped the egg on the ground as the bird was released and I yelled, “We’re free!” A few days later, I put on my gray pin-striped suit and went to court.

After the verdict had been delivered, my defense team had put together a presentence memorandum on my behalf. It was an impressive document. Dr. Jerome Miller, the clinical director of the Augustus Institute in Virginia and one of the nation’s leading experts on adult sex offenders, had examined me and concluded that I was “a sensitive and thoughtful young man with problems more the result of developmental deficits than of pathology.” With regular psychotherapy, he was convinced that my long-term prognosis would be quite good. He concluded, “A term in prison will delay the process further and more likely set it back. I would strongly recommend that other options with both deterrent and treatment potential be considered.” Of course, the probation officers who put together their sentencing document left that last paragraph out of their summary. But they were eager to include the prosecution’s opinion, “An assessment of this offense and this offender leads the chief investigator of this case, an experienced sex crimes detective, to conclude that the defendant is inclined to commit a similar offense in the future.”

My lawyers prepared an appendix that contained forty-eight testimonials to my character from such diverse people as my high school principal, my social worker in upstate New York, Sugar Ray Robinson’s widow, my adoptive mother, Camille, my boxing hypnotherapist, and six of my girlfriends (and their mothers), who all wrote moving accounts of how I had been a perfect gentleman with them. One of my first girlfriends from Catskill even wrote the judge, “I waited three years before having sexual intercourse with Mr. Tyson and not once did he force me into anything. That is the reason I love him, because he loves and respects women.”

But of course, Don being Don, he had to go and overdo it. King had the Reverend William F. Crockett, the Imperial First Ceremonial Master of the Ancient Egyptian Arabic Order Nobles Mystic Shrine of North and South America, write a letter on my behalf. The Reverend wrote, “I beseech you to spare him incarceration. Though I have not spoken to Mike since the day of his trial, my information is that he no longer uses profanity or vulgarity, reads the Bible daily, prays and trains.” Of course, that was all bullshit. He didn’t even know me.

Then there was Don’s personal heartfelt letter to the judge. You would have thought that I had come up with a cure for cancer, had a plan for peace in the Middle East, and nursed sick kittens back to health. He talked about my work with the Make-A-Wish Foundation visiting with sick kids. He informed Judge Gifford that every Thanksgiving we gave away forty thousand turkeys to the needy and the hungry. He recounted the time we met with Simon Wiesenthal and I was so moved that I donated a large sum of money to help him hunt down Nazi war criminals.

This went on for eight pages, with Don waxing eloquently about me. “It is highly unusual for a person his age to be concerned about his fellow man, let alone with the deep sense of commitment and dedication that he possesses. These are God-like qualities, noble qualities of loving, giving and unselfishness. He is a child of God: one of the most gentle, sensitive, caring, loving, and understanding persons that I have ever met in my twenty years’ experience with boxers.” Shit, Don should have delivered the closing arguments instead of my lawyer. But John Solberg, Don’s public relations man, cut right to the chase in his letter to Judge Gifford. “Mike Tyson is not a scumbag,” he wrote.

I might not have been a scumbag, but I was an arrogant prick. I was so arrogant in the courtroom during the trial that there was no way they were going to give me a break. Even in my moment of doom, I was not a humble person. All those things they wrote about in that report – giving people money and turkeys, taking care of people, looking out for the weak and the infirm – I did all those things because I wanted to be that humble person, not because I was that person. I wanted so desperately to be humble but there wasn’t a humble bone in my body.

So, armed with all my character testimonials, we appeared in Judge Patricia Gifford’s court on March 26, 1992, for my sentencing. Witnesses were permitted and Vince Fuller began the process by calling to the stand Lloyd Bridges, the executive director of the Riverside Residential Center in Indianapolis. My defense team was arguing that instead of jail time, my sentence should be suspended and I should serve my probation term at a halfway house where I could combine personal therapy with community service. Bridges, an ordained minister, ran just such a program and he testified that I would certainly be a prime candidate for his facility.

But the assistant prosecutor got Bridges to reveal that there had been four escapes recently from his halfway house. And when she got the minister to admit that he had interviewed me in my mansion in Ohio and that we had paid for his airfare, that idea was dead in the water. So now it was only a matter of how much time the Hanging Judge would give me.

Fuller approached the bench. It was time for him to weave his million-dollar magic. Instead, I got his usual two-bit bullshit. “Tyson came in with a lot of excess baggage. The press has vilified him. Not a day goes by that the press doesn’t bring up his faults. This is not the Tyson I know. The Tyson I know is a sensitive, thoughtful, caring man. He may be terrifying in the ring, but that ends when he leaves the ring.” Now, this was nowhere near Don King hyperbole, but it wasn’t bad. Except that Fuller had just spent the whole trial portraying me as a savage animal, a crude bore, bent solely on sexual satisfaction.

Then Fuller changed the subject to my poverty-stricken childhood and my adoption by the legendary boxing trainer Cus D’Amato.

“But there is some tragedy in this,” he intoned. “D’Amato only focused on boxing. Tyson, the man, was secondary to Cus D’Amato’s quest for Tyson’s boxing greatness.” Camille, who was Cus’s companion for many years, was outraged at his statement. It was like Fuller was pissing on the grave of Cus, my mentor. Fuller went on and on, but he was as disjointed as he had been for the entire trial.

Now it was my time to face the court. I got up and stood behind the podium. I really hadn’t been prepared properly and I didn’t even have any notes. But I did have that stupid voodoo guy’s piece of paper in my hand. And I knew one thing – I wasn’t going to apologize for what went on in my hotel room that night. I apologized to the press, the court, and the other contestants of the Miss Black America pageant, where I met Desiree, but not for my actions in my room.

I can’t repeat everything because I am limited in my ability to comment on my own trial owing to U.K. law. Then the judge asked me a few questions about being a role model for kids. “I was never taught how to handle my celebrity status. I don’t tell kids it’s right to be Mike Tyson. Parents serve as better role models.”

Now the prosecution had their say. Instead of the redneck Garrison, who argued against me during the trial, his boss, Jeffrey Modisett, the Marion County prosecutor, stepped up. He went on for ten minutes saying that males with money and fame shouldn’t get special privileges. Then he read from a letter from Desiree Washington. “In the early morning hours of July 19, 1991, an attack on both my body and my mind occurred. I was physically defeated to the point that my innermost person was taken away. In the place of what has been me for eighteen years is now a cold and empty feeling. I am not able to comment on what my future will be. I can only say that each day after being raped has been a struggle to learn to trust again, to smile the way I did and to find the Desiree Lynn Washington who was stolen from me and those who loved me on July 19, 1991. On those occasions when I became angry about the pain that my attacker caused me, God granted me the wisdom to see that he was psychologically ill. Although some days I cry when I see the pain in my own eyes, I am also able to pity my attacker. It has been and still is my wish that he be rehabilitated.”

Modisett put the letter down. “From the date of his conviction, Tyson still doesn’t get it. The world is watching now to see if there is one system of justice. It is his responsibility to admit his problem. Heal this sick man. Mike Tyson, the rapist, needs to be off the streets.” And then he recommended I do eight to ten years of healing behind bars.

It was Jim Voyles’s turn to speak on my behalf. Voyles was the local attorney hired by Fuller to act as local counsel. He was a great guy, compassionate, smart, and funny. He was the only attorney from my side that I related to. Besides all that, he was a friend of Judge Gifford’s and a down-home guy who could appeal to the Indianapolis jury. “Let’s go with this guy,” I told Don at the beginning of my trial. Voyles would have gotten me some play. But Don and Fuller made a fool out of him. They didn’t let him do anything. They shut him down. Jim was frustrated too. He described his role to one friend as “one of the world’s highest-paid pencil carriers.” But now he was finally arguing in court. He spoke passionately for rehabilitation instead of incarceration but it fell on deaf ears. Judge Gifford was ready to make her decision.

She began by complimenting me on my community work and my treatment of children and my “sharing” of “assets.” But then she went into a rant about “date rape,” saying it was a term she detested. “We have managed to imply that it is all right to proceed to do what you want to do if you know or are dating a woman. The law is very clear in its definition of rape. It never mentions anything about whether the defendant and victim are related. The ‘date,’ in date rape, does not lessen the fact that it is still rape.”

“I feel he is at risk to do it again because of his attitude,” the judge said and stared at me. “You had no prior record. You have been given many gifts. But you have stumbled.” She paused.

“On count one, I sentence you to ten years,” she said.

“Fucking bitch,” I mumbled under my breath. I started to feel numb. That was the rape count. Shit, maybe I should have drank that special voodoo water, I thought.

“On count two, I sentence you to ten years.” Don King and my friends in the courtroom audibly gasped. That count was for using my fingers. Five years for each finger. “On count three, I sentence you to ten years.” That was for using my tongue. For twenty minutes. It was probably a world record, the longest cunnilingus performed during a rape.

“The sentences will run concurrently,” she continued. “I fine you the maximum of thirty thousand dollars. I suspend four of those years and place you on probation for four years. During that time you will enter into a psychoanalytic program with Dr. Jerome Miller and perform one hundred hours of community work involving youth delinquency.”

Now Fuller jumped up and argued that I should be allowed to be free on bail while Alan Dershowitz, the celebrated defense attorney, prepared my appeal. Dershowitz was there in the courtroom, observing the sentencing. After Fuller finished his plea, Garrison, the redneck cowboy, took the floor. A lot of people would later claim that I was a victim of racism. But I think guys like Modisett and Garrison were just in it for the shine more than anything else. They didn’t really care about the ultimate legal outcome; they were just consumed with getting their names in the papers and being big shots.

So Garrison got up and claimed I was a “guilty, violent rapist who may repeat. If you fail to remove the defendant, you depreciate the seriousness of the crime, demean the quality of law enforcement, expose other innocent persons, and allow a guilty man to continue his lifestyle.”

Judge Gifford agreed. No bail. Which meant that I was heading straight to prison. Gifford was about to gavel the proceedings to an end when there was a commotion in the courtroom. Dershowitz had bolted up, gathered his briefcase, and loudly rushed out of the courtroom, muttering, “I’m off to see that justice is done.” There was some confusion but then the judge banged her gavel on her table. That was it. The county sheriff came over to take me into custody. I stood up, removed my watch, took off my belt and handed them, along with my wallet, to Fuller. Two of my female friends in the first row of spectators were crying uncontrollably. “We love you, Mike,” they sobbed. Camille got up and made her way to our defense table. We hugged good-bye. Then Jim Voyles and I were led out of the courtroom through the back door by the sheriff.

They took me downstairs to the booking station. I was searched, fingerprinted, and processed through. There was a mob of reporters waiting outside, surrounding the car that would take me to prison.

“When we leave, remember to keep your coat over your handcuffs,” Voyles advised me. Was he for real? Slowly the numbness was leaving me and my rage was kicking in. I should be ashamed to be shown with handcuffs? That’s my badge of honor. If I hide the cuffs, then I’m a bitch. Jim thought that hiding my cuffs would stop me from experiencing shame, but that would have been the shame. I had to be seen with that steel on me. Fuck everybody else, the people who understand, they have got to see me with that steel on. I was going to warrior school.

We exited the courthouse and made our way to the car, and I proudly held my cuffs up high. And I smirked as if to say, “Do you believe this shit?” That picture of me made the front page of newspapers around the world. I got into the police car and Jim squeezed next to me in the backseat.

“Well, farm boy, it’s just you and me,” I joked.

They took us to a diagnostic center to determine what level prison I would be sent to. They stripped me naked, made me bend down and did a cavity search. Then they gave me some pajama-type shit and some slippers. And they shipped me off to the Indiana Youth Center in Plainfield, a facility for level-two and -three offenders. By the time I got to my final destination, I was consumed with rage. I was going to show these motherfuckers how to do time. My way. It’s funny, but it took me a long time to realize that that little white woman judge who sent me to prison just might have saved my life.

We were beefing with these guys called the Puma Boys. It was 1976 and I lived in Brownsville, Brooklyn, and these guys were from my neighborhood. At that time I was running with a Rutland Road crew called The Cats, a bunch of Caribbean guys from nearby Crown Heights. We were a burglary team and some of our gangster friends had an altercation with the Puma Boys, so we were going to the park to back them up. We normally didn’t deal with guns, but these were our friends so we stole a bunch of shit: some pistols, a .357 Magnum, and a long M1 rifle with a bayonet attached from World War I. You never knew what you’d find when you broke into people’s houses.

So we’re walking through the streets holding our guns and nobody runs up on us, no cops are around to stop us. We didn’t even have a bag to put the big rifle in, so we just took turns carrying it every few blocks.

“Yo, there he goes!” my friend Haitian Ron said. “The guy with the red Pumas and the red mock neck.” Ron had spotted the guy we were after. When we started running, the huge crowd in the park opened up like Moses parting the Red Sea. It was a good thing they did, because, boom, one of my friends opened fire. Everybody scrambled when they heard the gun.

We kept walking, and I realized that some of the Puma Boys had taken cover between the parked cars in the street. I had the M1 rifle and I turned around quickly to see this big guy with his pistol pointed towards me.

“What the fuck are you doing here?” he said to me. It was my older brother, Rodney. “Get the fuck out of here.”

I just kept walking and left the park and went home. I was ten years old.

I often say that I was the bad seed in the family, but when I think about it, I was really a meek kid for most of my childhood. I was born in Cumberland Hospital in the Fort Greene section of Brooklyn, New York, on June 30, 1966. My earliest memories were of being in the hospital – I was always sick with lung problems. One time, to get some attention, I put my thumb in some Drano and then put it in my mouth. They rushed me to the hospital. I remember my godmother gave me a toy gun while I was there, but I think I broke it right away.

I don’t know much about my family background. My mother, Lorna Mae, was a New Yorker but she was born down south in Virginia. My brother once went down to visit the area where my mother grew up and he said there was nothing but trailer parks there. So I’m really a trailer park nigga. My grandmother Bertha and my great-aunt used to work for this white lady back in the thirties at a time when most whites wouldn’t have blacks working for them, and Bertha and her sister were so appreciative that they both named their daughters Lorna after the white lady. Then Bertha used the money from her job to send her kids to college.

I may have gotten the family knockout gene from my grandma. My mother’s cousin Lorna told me that the husband of the family Bertha worked for kept beating on his wife, and Bertha didn’t like it. And she was a big woman.

“Don’t you put your hands on her,” she told him.

He took it as a joke, and she threw a punch and knocked him on his ass. The next day he saw Bertha and said, “Well, how are you doing, Miss Price?” He stopped hitting on his wife and became a different man.

Everybody liked my mom. When I was born, she was working as a prison matron at the Women’s House of Detention in Manhattan, but she was studying to be a teacher. She had completed three years of college when she met my dad. He got sick so she had to drop out of school to care for him. For a person that well educated, she didn’t have very good taste in men.

I don’t know much about my father’s family. In fact, I didn’t really know my father much at all. Or the man I was told was my father. On my birth certificate it said my father was Percel Tyson. The only problem was that my brother, my sister, and I never met this guy.

We were all told that our biological father was Jimmy “Curlee” Kirkpatrick Jr. But he was barely in the picture. As time went on I heard rumors that Curlee was a pimp and that he used to extort ladies. Then, all of a sudden, he started calling himself a deacon in the church. That’s why every time I hear someone referring to themselves as reverend, I say “Reverend-slash-Pimp.” When you really think about it, these religious guys have the charisma of a pimp. They can get anybody in the church to do whatever they want. So to me it’s always “Yeah, Bishop-slash-Pimp,” “Reverend Ike-slash-Pimp.”

Curlee would drive over to where we stayed, periodically. He and my mother never spoke to each other, he’d just beep the horn and we’d just go down and meet him. The kids would pile into his Cadillac and we thought we were going on an excursion to Coney Island or Brighton Beach, but he’d just drive around for a few minutes, pull back up to our apartment building, give us some money, give my sister a kiss, and shake me and my brother’s hands and that was it. Maybe I’d see him in another year.

My first neighborhood was Bed-Stuy in Brooklyn. It was a decent working-class neighborhood then. Everybody knew one another. Things were pretty normal, but they weren’t calm. Every Friday and Saturday, it was like Vegas in the house. My mom would have a card party and invite all her girlfriends, many of whom were in the vice business. She would send her boyfriend Eddie to buy a case of liquor and they’d water it down and sell shots. Every fourth hand of cards the winner had to throw into the pot so the house made money. My mom would cook some wings. My brother remembers that, besides the hookers, there’d be gangsters, detectives. The whole gamut was there.

When my mother had some money, she’d splurge. She was a great facilitator and she’d always have her girlfriends over and a bunch of men too. Everybody would be drinking, drinking, drinking. She didn’t smoke marijuana but all her friends did, so she’d supply them with the drugs. She just smoked cigarettes, Kool 100’s. My mother’s friends were prostitutes, or at least women who would sleep with men for money. No high-level or even street-level stuff. They would drop off their kids at our house before they went to meet their men. When they’d come to pick up their kids, they might have blood on their clothes, so my mom would help them clean up. I came home one day and there was a white baby in the house. What the fuck is this shit? I thought. But that’s just what my life was like.

My brother Rodney was five years older than I was so we didn’t have much in common. He’s a weird dude. We’re black guys from the ghetto and he was like a scientist – he had all these test tubes, was always experimenting. He even had coin collections. I was, like, “White people do this stuff.”

He once went to the chemistry lab at Pratt Institute, a nearby college, and got some chemicals to do an experiment. A few days later when he went out, I snuck into his room, started adding water to his test tubes, and I blew out the whole back window and started a fire in his room. He had to put a lock on his door after that.

I fought with him a lot, but it was just typical brother stuff. Except for the day that I cut him with a razor. He had beaten me up for some reason and then he had gone to sleep. My sister, Denise, and I were watching one of those doctor-type soap operas and they were doing an operation. “We could do that and Rodney could be the patient. I can be the doctor and you can be the nurse,” I told my sister. So we rolled up his sleeve and got to work on his left arm. “Scalpel,” I said, and my sister handed me a razor. I cut him a bit and he started bleeding. “We need the alcohol, nurse,” I said, and she passed it to me and I poured it onto his cuts. He woke up screaming and yelling and chased us around the house. I hid behind my mom. He still has those slices to this day.

We had some good times together too. Once, my brother and I were walking down Atlantic Avenue and he said, “Let’s go to the doughnut factory.” He had stolen some doughnuts from that place before and I guess he wanted to show me he could do it again. So we walked by and the gate was open. He went in and got a few boxes of doughnuts, but something happened and the gate closed and he was stuck in there and the security guards started coming. So he handed me the doughnuts and I ran home with them. My sister and I were sitting on our stoop and cramming down those doughnuts and our faces were white with the powder. Our mom was standing next to us, talking to her neighbor.

“My son aced the test to get into Brooklyn Tech,” she boasted to her friend. “He is such a remarkable student, he’s the best pupil in his class.”

Just then a cop car drove up and Rodney was in it. They were going to drop him off at home, but he heard our mother bragging about what a good son he was and he told the cops to keep going. They took him straight to Spofford, a juvenile detention center. My sister and I happily finished off those doughnuts.

I spent most of my time with my sister Denise. She was two years older than me and she was beloved by everybody in the neighborhood. If she was your friend, she was your best friend. But if she was your enemy, go across the street. We made mud pies; we watched wrestling and karate movies and went to the store with our mother. It was a nice existence, but then when I was just seven years old, our world got turned upside down.

There was a recession and my mom lost her job and we got evicted out of our nice apartment in Bed-Stuy. They came and took all our furniture and put it outside on the sidewalk. The three of us kids had to sit down on it and protect it so that nobody took it while my mother went to find a spot for us to stay. I was sitting there, and some kids from the neighborhood came up and said, “Mike, why is your furniture out here, Mike?” We just told them we were moving. Then some neighbors saw us out there and brought some plates of food down for us.

We wound up in Brownsville. You could totally feel the difference. The people were louder, more aggressive. It was a very horrific, tough, and gruesome kind of place. My mother wasn’t used to hanging around those particular types of aggressive black people and she appeared to be intimidated, and so were my brother and sister and me. Everything was hostile, there was never a subtle moment there. Cops were always driving by with their sirens on; ambulances always coming to pick up somebody; guns always going off, people getting stabbed, windows being broken. One day my brother and I even got robbed right in front of our apartment building. We used to watch these guys shooting it out with one another. It was like something out of an old Edward G. Robinson movie. We would watch and say, “Wow, this is happening in real life.”