Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Hold: An Observer New Face of Fiction 2018"

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2018

Copyright © Michael Donkor 2018

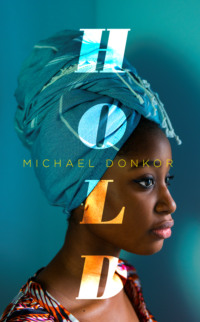

Cover photograph © Plainpicture/R. Mohr

Cover design by Jack Smyth

Michael Donkor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

‘Michicko Dead’ from The Great Fires: Poems, 1982–1992 by Jack Gilbert, copyright © 1994 by Jack Gilbert. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008280345

Ebook Edition © July 2018 ISBN: 9780008280369

Version: 2018-06-07

Dedication

For Patrick Netherton and Grace Opoku

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Twi terms, phrases and expressions

December 2002

SPRING

1

2

3

SUMMER

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

AUTUMN

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

WINTER

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Twi terms, phrases and expressions

Aane – Yes

Aba! – Exclamation of annoyance, disdain or disbelief

Aboa! – You beast!

Abrokyrie – Overseas

Abrokyriefoɔ – Foreigners

Abusuafoɔ – Extended family

Adɛn? – Why?

Adjei! – Exclamation of surprise or shock

Agoo? – May I come in?

Akwaaba – Welcome

Akwada bone! – Naughty child!

Amee – Please enter

Ampa – It’s true

Ewurade – God

Ɛfɛ paaa – Very nice

Fri hɔ! – Go away!

Gyae – Stop

Gye nyame – Traditional symbol meaning ‘only God’

Hwɛ – Look

Hwɛ w’anim! – Look at your face!

Kwadwo besia – An ‘effeminate’ man

Maame – Miss/Mistress

Me ba – I am coming

Me boa? – I lie?

Me da ase – I thank you

Me nua – My sibling

Me pa wo kyew/me sroe – Please (I beg you)

Me yare – I am sick

Nananom – Elders

Oburoni – White person

Oburoni wawu – Second-hand clothes (‘the white man is dead’)

Paaa – Sign of emphasis

Sa? – Really?

Wa bo dam! – You are mad!

Wa te? – Do you hear?

Wa ye adeɛ – Well done

Wo se sɛn? – What did you say?

Wo wein? – Where are you?

Wo ye … – You are …

Won sere? – You won’t laugh?

Yere – Wife

December 2002

The coffin was like a neat slice of wedding cake. Looping curls of silver and pink, fussy like best handwriting, wound around the box. It waited by the gashed earth that the men would rest it in. The mourners admired, clucking. Belinda made herself look at it. Her phone vibrated in her handbag but she let it rumble on. She brought her ankles together, fixed her head-tie and straightened her dress so that it was less bunched around her breasts. She passed her hand over her puffy face and then saw that eyeliner had rubbed onto her palm in streaks.

Belinda’s inspection of her messy hands was interrupted by the shouting of the young pallbearers on the opposite side of the grave. They stripped off and swirled the cloths that had been draped over their torsos moments before, then called for hammers. Three little boys, perhaps six or seven years old, flitted back with tools heavier than their tiny limbs. The children hurried off with handfuls of sweet chin chins, nearly falling into the hole not meant for them and only laughing light squeals at how narrowly they had avoided an accident. Belinda wondered if she had ever laughed like that when she was their age.

The men started to thud away the casket’s handles, eager for the shiniest decorations, the ones that would fetch the highest prices in the market. She knew it was what always happened at funerals, and that the bashing and breaking was no worse than anything else she had seen in the last few hours – but as the men’s blows against the handles kept on coming, the sound became a hard hiccupping against Belinda’s skull. Her chin jutted forward like it was being pulled and her whole body tightened. Belinda tapped the heel of her court shoe into the red earth, matching her galloping blood. Soon, wrenched free of its metal, the coffin’s surfaces were all marked with deep black gouges.

Someone tried to move Belinda with a shove. She remained where she stood. The pallbearers strutted and touched their muscles. Some yelped for the crowd to cheer. There were whines from older mourners about sharing, relatives and fairness.

‘Sister!’ an excitable man said, pushing a brassy knob towards Belinda. She let it fall from his grasp and roll at her feet. It was not enough.

SPRING

1

Daban, Kumasi – March 2002

Belinda fidgeted in the dimness. She sat up, drawing her knees and the skimpy bedsheets close to her chest. Outside, the Imam’s rising warble summoned the town’s Muslims to prayer. The dawn began to take on peaches and golds and those colours spread through the blinds, across the whitewashed walls and over the child snuffling at Belinda’s side.

All those months ago, on the morning that they had started working in Aunty and Uncle’s house, Belinda and Mary had been shown the servants’ quarters and were told that they would have to share a bed. To begin with, Belinda had found it uncomfortable: sleeping so close to a stranger, sleeping so close to someone who was not Mother. But, as with so many other things about the house, Belinda soon adapted to it and even came to like the whistling snore Mary often made. On that bed, each and every night, Mary slept in exactly the same position; with her small body coiled and her thumb stopping her mouth. Now Belinda watched Mary roll herself up even more tightly and chew on something invisible. She thought about shifting the loosened plait that swept across Mary’s forehead.

Belinda turned from Mary and moved her palms in slow circles over her temples. The headache came from having to think doubly: once for Mary, once for herself; a daily chore more draining than the plumping of Aunty and Uncle’s tasselly cushions, the washing of their smalls, the preparing of their complicated breakfasts.

Dangling her legs down and easing herself to the floor, Belinda quietly made her way to the bathroom. She stepped around the controller for the air con they never used and around the remains from the mosquito coil. She brushed by the rail on which their two tabards were hung. Belinda remembered the first time Aunty had said it – ‘tabard’ – and how confused Mary’s expression had become because of the oddness of the word and the oddness of the flowery uniform Aunty insisted they wear when they cleaned. Belinda would miss that about Mary’s face: how quickly and dramatically it could change.

Under the rusting showerhead, Belinda scrubbed with the medicinal bar of Neko. Steam rose and water splashed. In her mind Belinda heard again the sentences Aunty had promised would win Mary round. She yanked at a hair sprouting from her left, darker nipple, pulling it through bubbles. The root gathered into a frightened peak. She liked the sensation.

Returning to the bedroom, in the small mirror she was ridiculous: the heaped towel like a silly crown. For a moment, she forgot the day’s requirements, and flicking her heels she pranced across the thin rug. Would Amma like that? Might jokes help heal that broken London girl? Or perhaps Belinda would be too embarrassed.

Mary shot up from beneath the covers and launched herself at Belinda’s chest. Belinda pushed her off and Mary lost her balance, fell onto the bed.

‘What is this? Are you a –? Are you a stupid –’ Belinda lifted the towel higher. ‘Grabbing for whatever you want, eh?’

‘What you worried for?’ Mary arched an eyebrow. ‘I have seen all before. Nothing to be ashamed for. And we both knowing there is gap beneath shower door and I’m never pretending to be quiet about my watchings neither. You probably heard me while I was doing my staring. Even maybe you seen my tiny eye looking up,’ Mary squinted hard, ‘and you’ve never said nothing about nothing. So I think you must relax now. I only’ – Mary tilted her head left, right, left – ‘wanted to see how yours are different from mine.’ She pulled up her vest and Belinda quickly rolled it down. A ringing quietened in Belinda’s ears.

‘And, and here is me ready to speak about treats for you,’ Belinda began.

‘You mean what? Miss Belinda?’ Mary folded her arms. ‘Adjei! You standing there in a silence to be so unfair. Adɛn? I want to hear of this my special thing. Tell of it!’

‘Less noise, Mary! You know Aunty and Uncle they have not yet woken.’

‘Then tell the secret and I will use my nicest, sweet voice.’

Belinda headed towards the mirror and adjusted its angle slightly. ‘Number one is that we have a day off.’

‘Wa bo dam! Day off?!’

‘Aane.’

‘Day. Off. Ewurade. When, when have they ever given us one of those?’ Mary rubbed her hands together. ‘Today no getting them nasty stringy things from the drain in the dishwasher? No scrubbing the coffee stain on Uncle’s best shirt again, even though everyone knows the mark is going to live there forever and ever amen!’

Mary laughed but soon stopped to count her stubby fingers. ‘You said number one. And you said treats not treat. I know the thing called plurals. You speak as if we also having two and three and four and even more. So you have to complete please, Miss Belinda. What else?’

‘Many great gifts from Aunty, Uncle and their guests Nana and Doctor Otuo. Many. But, but I will let them know they should change their minds and their plan. Because why should a naughty little girl get good things?’

‘That question is too easy. Nasty people get nice all the time. Look at Uncle. He is farting in the night and afternoon, and then blaming it on Gardener or anyone else passing.’ Mary threw up her arms. ‘But he still got treasures from the UK and this massive palace he lives in with his own generator, own two housegirls in me and you and all kinds of rich visitors coming in.’

‘Ah-ah! Your Uncle never, never farted! Take that one back.’

‘What else is my treat?’

‘Wait and see,’ Belinda said.

2

Later that morning, under the fierce sun, for what felt to Belinda like hours they waited at the end of a long line outside Kumasi Zoo’s gates. They stood behind three nurses who had powerful bottoms and who passed the time by repeatedly humming the old hymn about the force of God’s constant love. Mary played with the green baubles Belinda had tied into her hair after she had promised to never again spy on Belinda showering. As they continued to queue, Mary crunched shards of dead banana leaves under her sandals and chattered away. Belinda tuned into and out of that overexcited flow of words: one of the larger clouds above, Mary was convinced, was shaped just like a fat man bending to touch his toes.

When they reached the stewardess in the crumbling admission booth, Belinda peeled and counted out cedis from the bundle of notes Nana and Aunty had given her. As Belinda paid, she became aware that Mary’s talking had stopped. Belinda watched Mary stare at the stewardess. The cool seriousness of Mary’s gaze made her seem much older than eleven. The little girl’s grave eyes moved; to the young woman’s hands that rested on a stack of brochures, to the polished things on the stewardess’ shoulder pads, finally stopping on the stewardess’ cap.

‘Madam,’ Mary said, suddenly beaming, ‘I have to tell you, this your hat is very fine and well. So smart and proper. I like this golden edge it has a lot. Big congratulations on wearing it.’

‘This is a most righteous praise.’ The stewardess leaned forward, and with her face now poking out of the booth’s shadows, her features were more visible to Belinda; the unusual fineness of the nose and cheekbones, the glossiness of her weave. ‘What a polite and best-mannered young lady we have on our grounds this pleasant day. Wa ye adeɛ.’

Mary stood tall. ‘The hat it looks like they made from a very beautiful and special material. Is it true? Can I please have one touch? I will not do any damages on it.’

‘Aba!’ Belinda tugged Mary’s shirt. ‘We not coming here to cause a nuisance or distraction for this officer. Let us go, please.’

‘Is not a problem. I see no other visitors behind you at this time,’ the stewardess offered.

‘See, is not a problem.’ Mary imitated the stewardess’ casualness perfectly, shrugged and reached out. Belinda saw how much the hat’s stiffness and texture seemed to please Mary. Mary began asking the stewardess how long she had had a job at the zoo, and what her favourite and worst things about working there were and which animals were the most annoying. Belinda jiggled her shoulders and pulled at the silly flouncy dress Nana and Aunty said she should wear because it was an important occasion. But even though she knew there were things to be done and things that she wanted done quickly, Belinda let Mary carry on. It seemed only fair.

The stewardess removed her fancy hat and placed it on Mary’s head at an angle. The hat was far too big. The two of them found this very amusing. Now the stewardess whistled and called for one of her colleagues – a thin man with a square afro and sore patches around his mouth – to replace her in the booth, and she then offered to give the girls a tour. Mary did a wiggling dance of joy before marching forward. Belinda pulled at her dress again but stopped herself in case she ripped it.

Belinda wished having fun was more natural for her. When Nana and Aunty had called her out to the veranda earlier in the week to have the conversation that had started everything, the two women told her her face was too long. Nana and her husband Doctor Otuo had been staying at the house for a fortnight. Throughout their visit Belinda had been intrigued by the novelty of their preferences, how happy they were when tea was the exact ‘right’ temperature. But, as Belinda stood at the end of the veranda on that Tuesday evening, holding her hands behind her back, she was more confused than intrigued by Nana’s advice that she ‘be more lightened up’. Belinda saw no reason to relax: usually, once Belinda and Mary had taken the dinner plates away and cleaned down the kitchen’s granite and marble, Aunty dismissed them. Then they had two uninterrupted hours of recreation time before lights out. Belinda had never been asked to return to the table after the evening meal was over. So she assumed she had made a mistake: perhaps the egusi stew had not been seasoned properly.

Waiting to hear her fate, a little dazzled by the stars decorating the sky and the candles she and Mary had placed everywhere at Aunty’s request, Belinda had tried her best to be more at ease. She placed her arms at her sides loosely and tilted her head. In response, Aunty and Nana did sharp laughs at one another. Their chunky bracelets clattered and their wicker chairs creaked. They took sips of Gulder before falling silent. Every now and again, Belinda watched the oleanders in the garden as they trembled in the breeze, but then she worried that might seem rude so she focused on the two women as much as she could. Aunty complimented Belinda’s hard work and effort, which made Belinda’s tabard feel less restricting.

Nana nodded, her indigo headscarf wobbling a little as she did so. ‘You doing really very well here, that’s true. I have seen your greatness for myself during our holidaymaking here. Even before I came to this place you should hear how your Aunty she praised you in every email she sent from her iBook PC, telling me of how she doesn’t even have to lift one tiny finger ever, and of how you show a fine honour in all you do, how you making their retirement so beautiful and wonderful. I am so pleased for my dearest friend.’

‘Me da ase,’ Belinda said softly.

Aunty invited Belinda to sit, so Belinda did.

Nana went on, ‘Especially the way you are with Mary. This sensible, calm way. I think that is really very good. You guiding her and caring for her. Is a blessed thing to watch.’

‘Is so very nice to hear this. I thank God for all the blessings we receive in this house. Aunty and Uncle have shown a big kindness to me. And to Mary also. Is miracle my mother saw the small card for this job in Adum Post Office. Miracle paaa. I believe the Almighty helped them choose me.’ When she finished speaking, Belinda felt breathless. Even the briefest reference to Mother could make her throat dry and strange.

For a time, no one spoke. Aunty flicked her Gulder’s bottle-top. Belinda sucked in her lower lip. Eventually Nana tossed a napkin onto the table like it had offended her. ‘Belinda. I will talk to you as a grown woman. Is that OK? No beating on bushes, wa te? I have to come direct to you because is the way of our people and will always be our way, wa te?’

‘Aane.’

‘Me I have a daughter in London. Amma. She is seventeen, very close to your own age. Maybe your Aunty has spoken of her. She is my one and only.’ Nana unclasped her earrings and rattled them in her palm like dice. ‘Let me tell you; she is very beautiful girl and the book-smartest you will ever find in the UK. Ewurade! Collecting only gold stars and speaking of all these clever ideas I haven’t the foggiest. They even put her in South London Gazette once because of her brains!’ Nana shook her head in disbelief. ‘And when she has a break from doing her homeworks or doing paintings, we shop together in H&M and have nice chats. And she makes her father very proud so he doesn’t even mind that he lacks a son and he never moans of how dear the private school fees are for his bank balance.’

Belinda took the napkin and folded it into quarters. ‘Daznice,’ she said. ‘Sounds very nice for you.’

‘It used to be nice.’ Nana sighed, put down her Gulder. ‘Past. We have to use past tense because is now lost and gone, you get me? As if in the blinking of a cloud of some smoke she has just become possessed. Not talking. Grumpy. Using just one word, two words for communication. As if she is carrying all of the world on her shoulders. Me, I am always trying to understand and asking her questions to work out what is happening to her, but I get nothing back. Only some rude cheekiness.’

‘Madam. I am very sorry for this one.’

Nana hissed. ‘And every stupid person in the world keeps talking to me about her hormones, hormones, hormones, but is more than this. I feel it. A mother knows. And her pain is paining me.’ Aunty patted Nana’s shoulder in the encouraging way that Belinda often did to Mary.

So Nana started to explain, drinking a little more and fussing whenever mosquitos came near her. When Nana spoke, she kept saying ‘if’ a lot, and saying it very slowly, as though Belinda had a choice to make. Nana talked and talked of her daughter’s need for a good, wise, supportive friend like Belinda to help her. Smiling with excellent, gapless teeth, Nana listed the opportunities Belinda would enjoy if she came over to London to stay with them, said that Belinda could improve her education in a wonderful London school and get a future; said that, like Aunty and Uncle had, she and Doctor Otuo would send Mother a little money each month to help her because they knew Mother’s shifts at the bar didn’t pay enough. The talking about Mother’s job at the chop bar, the thickness of Nana’s perfume, the idea of moving again – all of it made Belinda feel weightless and sick; like her chest was full of strange, drifting bubbles.

For a moment, Nana turned to Aunty. The two women held hands, their rings clicking against each other and their bracelets jangling again. ‘Belinda,’ Aunty exhaled, ‘is a total heartbreak and pain for me to let you go. Feels too soon. Like you have been here some matter of days, and already –’

‘Six months and some few weeks.’

‘What?’

‘Mary and I have been here six months and maybe two weeks in addition.’

‘Yes,’ Aunty said, now touching the papery skin at her throat. ‘And that is a heartbreak. But this is what my great friend says she needs and what Amma needs. So, out of a loyalty and from a care, I let you go.’

Belinda traced the silver pattern marking the napkin’s edge. The cicadas played their long, dull tune. She had so many questions but found that her mouth only asked one: ‘You mentioning just me. What of Mary? She stays here?’

‘Yes,’ Nana said without eye contact, ‘she stays here.’

‘Oh. Oh.’ Belinda concentrated on the napkin again but its busy design became too much for her.

Nana and Aunty behaved like everything would be easy. Belinda worried it would not be. Even so, she nodded along then got down on her knees to thank them because she knew her role and place, understood how things should be. And, at their feet, she bowed her head and gave praise in quiet phrases because getting further away from what she had left in the village was more of a blessing than either Nana or Aunty could understand.

It was decided that Belinda should take Mary out for a day trip to tell her the news. Let her have a bit of sugar to help swallow the pill. It was decided that a visit to the zoo would be just right. It was decided that they had struck on a great plan. And so, in a voice faraway and unlike her own, Belinda told them Mary would like the zoo, especially seeing the monkeys, because Mary loved the cleverness of their tails.

But now, as Belinda and Mary stopped at a water fountain near the snakes’ enclosure to wait for the stewardess to take a gulp, Mary seemed much more interested in ostriches than monkeys.

‘So, where are they hiding?’ Mary demanded, pointing at a grainy picture of the birds in the brochure.

The stewardess wiped her mouth and admired the lushness in front of them, a wooden stick clutched under her arm. Belinda studied the view too. Sighing, Mary snapped away with the tiny camera borrowed from Aunty. The zoo was beautiful, rich with orchids shooting from dark bushes like eager hands, thickening the air with sweetness. Cashew trees were everywhere, loaded with leathery fruit. Even the lizards here seemed different, striped with hotter colour. Small streams cut across the land, flickering with unknown fish. Every now and again, the tops of trees rang with cries.

‘The ostriches?’ Mary asked firmly.

‘If you revise your memory of the noticeboard encountered on your entry, you will recall that we have sadly to inform you of this suspension of this ostriches. They have been removed from our care due to budget cut. Me, I’m not supposed to be revealing to you such. I’m to declare this ostriches has been loan to a Washington Zoo, in United States of America, so it gives us a prestige and you feel proud your nation’s zoo-oh, giving its animals to the West.’ The stewardess pushed the sweaty licks of hair from her eyes. ‘Sorry. Is lie. We have sold our ostriches. Sold. Because how can you be keeping grand big birds in country like this when too many here still have no simple reading, writing and such things?’

‘Cro-co-diles here!’ Mary pointed to the words on a sun-bleached arrow. Belinda’s arm swung as Mary released her grip and skipped up a dirt track.

‘Careful, oh! He come from the Northern region – and we have left him unfed for some four days – budget cuts!’ The stewardess headed in Mary’s direction.

Following, walking through foliage, Belinda bit her nails, spitting out the red varnish that broke onto her tongue. Belinda wanted the right sort of place: somewhere hidden; theirs for that moment. But visitors busy with their own intimacies occupied all places the path led. An Indian couple wearing matching baseball caps, necks looped with binoculars, sat on a bench. A father near the porcupines opened his briefcase in front of three waiting children. The three nurses from the entry queue unlinked their hooked arms; one stopped to rub her hip. And if that wasn’t bad enough, there were no pockets on Belinda’s dress, and so after Mary got a generous share of the cash Belinda had been given to pay for the day, Belinda squeezed the remaining cedis into her bra, giving herself an uncomfortable, monstrous breast. The high-heels Aunty and Nana said made her feet ‘feminine’ pinched her toes and were more painful than stomach cramps.

‘I face the most severe of high recriminations if the girl comes lost. Akwada bone! Wo wein?’ The stewardess hopped, checked the air around her, shouted in the direction in which Mary had sped off. ‘This crocodile will be bearing the most emptiest of stomachs, small child. He will come, snapping for even your no-meat ankles. You must exact caution!’

Mary jumped up from behind a tree. Belinda leapt with shock.

‘Why does budget cut have to mean bad signs?’ Mary asked the stewardess. ‘I mean how long we have been walking for and have I seen one cro-co-dile? No, Mrs. No even one of them to snap at my size-five feet.’

‘This one has so much lip!’ The stewardess became suddenly playful, extending her hand to Mary.

‘You will take me?’

‘I will take you.’

Mary asked the stewardess her name, then asked if she was married and about being married. Behind, wrestling with the layers of her long gold dress, Belinda remembered what women claimed about fat-cheeked babies who did not cry when they were passed between relatives. ‘Oh, he is such a good boy – he goes to anyone!’ Though she would have hated being compared like that, Mary had that same ease. Belinda wiped away something sticky from her neck, fallen from the canopy above. She considered beginning with reassurances about the smallness of the loss. There would be a new Belinda soon, surely. Another plain girl from some bush-place, come to clean Aunty and Uncle’s fine-fine retirement villa nicely. All Mary needed to do was introduce herself politely, show this housegirl where the towels and things were, and then they could start. It would be easy to go to this new Belinda. Good for Mary, even. Yes. But Belinda knew Mary would ask if she herself was so replaceable; if a new Mary would be found so easily. Belinda could not mention Amma.

Ahead, through the heat’s shimmers, the stewardess ‘Priscilla’ lifted her staff, pushed a curtain of leaves aside and ushered Mary beneath. Belinda stumbled forward. Tired fencing and browning grasses ringed the swamp. Dragonflies and midges rose and fell in the steam. Broken wood and lengths of something like soiled rope drifted across the surface and Belinda understood their slowness. Peaks of mud forced up through the water. A dripping sound worried the silent air and the sickly light.

‘Ladies and no gentleman, I am presenting … Reginald!’

Mary applauded, but soon Belinda saw her face squash when it became obvious that the clapping fell deafly. Cross-legged on the wet soil where Priscilla joined her, Mary said, ‘I don’t like Reginald for a crocodile’s name. Tell me his local one. On, on which day was he born?’

‘He arrived here some three years. Big men brought him in a truck all far from Bolgatanga.’

‘Which. Day. Please?’

‘I believe the delivery came on a Tuesday, so –’

‘So we will say that. Let us call for Kwabena. Come.’ Belinda made her way to them, cursed the shoes, squatted as the other two did, and clapped towards the water. ‘Kwabena?! Aba! Eh? You want to be shy? Adɛn?’

Nothing. Nothing but stillness.

‘There are, erm, tarantulas also for us to show you? Erm.’

‘I hate spiders. And anyway, I have spiders at my house, at my Aunty and Uncle house where I do clean, we do cleaning, Ino be so, Belinda? They, they come into bathroom. They don’t mind the cockroaches. Neither do we.’ Mary shifted her attention between Belinda and Priscilla dizzily and then became strict. ‘They not our real Uncle or Aunty, by the way. But you know how we have to use these words for our elders out of a tradition and respect and I am a 100 per cent respectful child.’