Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

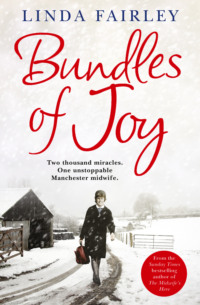

Buch lesen: "Bundles of Joy: Two Thousand Miracles. One Unstoppable Manchester Midwife"

Copyright

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the author’s experiences. In order to protect privacy, names, identifying characteristics, dialogue and details have been changed or reconstructed.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

and HarperElement are trademarks of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

First published by HarperElement 2012

FIRST EDITION

© Linda Fairley with Rachel Murphy 2012

All images and material © the author, except where stated. Associated Press extract and Tameside Hospital NHS Foundation Trust article reproduced with permission.

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of the material produced herein and secure permission to use it, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any future edition of this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Linda Fairley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN 9780007457144

Ebook Edition © October 2012 ISBN: 9780007457151

Version 2016-10-21

ALSO BY LINDA FAIRLEY

The Midwife’s Here!

For Peter,

who told me I could do this.

He would be very proud.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Also by Linda Fairley

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter One

‘I’d love to hear some good news’

Chapter Two

‘Please God, look after Mrs Sully this time’

Chapter Three

‘W-w-what did I do wrong?’

Chapter Four

‘I think I’ve eaten far too much turkey’

Chapter Five

‘Help me! I’m boiling me ’ead off!’

Chapter Six

‘Mind if I have a ciggie, only I’m really nervous?’

Chapter Seven

‘What an impatient little boy you are!’

Chapter Eight

‘Oh Christ, the head is coming out!’

Chapter Nine

‘The bigger the medallion, the harder they fall’

Chapter Ten

‘I haven’t felt the baby move’

Chapter Eleven

‘I was hoping to apply for a community post’

Chapter Twelve

‘Shoo you great oaf!’

Chapter Thirteen

‘Honestly, you could have been killed!’

Chapter Fourteen

‘Linda, I’ve got some terrible news’

Chapter Fifteen

‘It wasn’t how I’d envisaged the birth at all!’

Chapter Sixteen

‘Now we have four midwives!’

Epilogue

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

‘Go, and do thou likewise.’

Prologue

‘She’s on the bathroom floor!’ Sarah’s husband puffed as he flung open the front door and ushered me inside the house. ‘Come in,’ he said urgently, giving me a grateful smile. ‘You must be frozen.’ Turning his head towards the stairs, he shouted up to his wife, ‘The midwife’s here! Love, the midwife’s here!’

Robin Heywood then turned on his heel and charged upstairs. I hastily pulled off my Wellington boots and winter coat and followed him, dripping water all over the carpet as I did so.

It was just before Christmas 2002 and I’d driven and trudged through deep snow to get here. Sarah Heywood hadn’t planned a home birth and when her waters broke her husband had called an ambulance in the hope they could make it to Tameside Hospital, where she was booked in to have her baby.

Snow was already thick on the ground and still falling fast when I received the call at my home in Mottram, asking me to head up to their house in the Glossop hills, some three miles away. In situations like this it’s standard practice to send an ambulance as well as two community midwives, in case it’s too late to get the patient to hospital. One of my colleagues would also have had a call to provide me with back-up, though she was not here yet.

It was past 10 p.m. when my phone rang in my sitting room. I wasn’t actually on duty, but as I drove a 4 x 4 and lived closest, I agreed to help. I must admit I wasn’t entirely thrilled about this. My husband Peter and I were watching television and I had been feeling very cosy, cuddled up on the settee, drinking hot tea and warming my toes in front of the fire. We’d spent the evening wrapping presents and I’d baked a batch of mince pies, which filled our home with a wonderful festive smell.

‘What a night to be called out,’ I grumbled as I went to get changed into my uniform.

‘Well, you won’t be complaining about wearing trousers on a night like this, that’s for sure,’ Peter commented as he looked out at the wintry night.

He was right. In these conditions the only saving grace, if you could call it that, was that I no longer had to wear a dress to work. My NHS uniform had changed in 2000 to navy trousers and a matching cotton tunic, which I wasn’t sure about at first. I remember that, not long before trousers came in, I’d been called out very urgently to a delivery, and for the first time ever I’d rushed out in my own clothes to save time changing. I found this was a big mistake. Even though the delivery went very well, I just didn’t feel right at all.

Without my uniform I didn’t actually feel like ‘Linda the midwife’. I was just Linda, the person I am when I am off duty and, though I’m sure it didn’t show, I felt somehow unprofessional. I vowed never to do that again, but when the modern trouser suit uniform was first unveiled I had my misgivings. It seemed so far removed from the days when I wore long skirts, starched cuffs and stockings and suspenders during my nurse’s training in the 1960s, and I wondered if I would feel suitably attired and ready for action.

In fact, my fears were unfounded. The trousers proved to be very smart and practical, and on nights like this they were an absolute godsend.

A colleague at the hospital had informed me that Sarah had gone into labour with her first baby on her due date but had been too afraid to venture out in the snow, for fear of getting stuck and having to have the baby in the car.

I shivered as I stepped out onto my driveway, crisp new flakes of snow crunching under the soles of my black shoes. Peter always helped me start my car in the winter. He was a gem at times like this, and as he cleared the snow off the windscreen I began to check my A–Z as I didn’t recognise the name of the road despite having worked in Glossop for many years. With this not being a scheduled home birth I had never visited Sarah before. I had not seen her at antenatal clinic, either, but that was not unusual as I typically shared a case load of about 80 ladies at any given time with the two other community midwives in my team, Helen and Angela. I realised as soon as I studied the route that I might have difficulty reaching the address, because it was in a remote part of Glossop, well off the beaten track.

As I navigated the near-empty roads taking me out of Mottram and towards Glossop, thick, icy snowflakes were bearing down on the windscreen of my Honda CRV. I had the heating on full blast, but I could still feel the bitter cold penetrating the fogged-up windows. It was 10.15 p.m. by now, and visibility was poor. Every road I drove down seemed to be darker and quieter than the last. The sky felt very low above me, crowding in on me as it deposited a relentless barrage of snowflakes on the roof of the car. Only the occasional flash of fairy lights blinking from a porch, or the twinkling of a Christmas tree in a window broke up the white landscape stretching and deepening around me.

I turned on the radio and was heartened to hear some Christmas carols tinkling out of the car speakers. I might have been reluctant to leave my warm and cosy house, but deep down I felt pleased to be helping a pregnant woman in her hour of need, sharing this precious night with her.

It took me about twenty minutes to reach Hathersage Drive, a main road on the east side of Glossop, which runs parallel to the picturesque Derbyshire Level and close to a golf course. I was used to seeing rolling hills and green grass from here, but everything was white except for the blue flashing light from a parked ambulance that now came into view.

Sarah’s house was down a narrow lane leading off Hathersage Drive, but I knew as soon as I saw the ambulance parked up at the top of the lane that it was not possible to drive any closer. I pulled up behind the ambulance, had a quick word with the driver, who confirmed I was at the right address, and headed down the lane, delivery pack in hand.

I was wearing a jacket and gloves, and Peter had made sure I had my Wellington boots with me, but I hadn’t expected to have to walk such a distance. It was several hundred yards down the lane and the snow was so deep in places that I could feel the cold and wet going down inside my boots and through my trousers. I’d never seen such deep snow, in fact, and I had to take big, wading strides to get through it. I wanted to phone ahead, but when I pressed the buttons on my mobile phone with my cold fingers, I found I had no signal.

More snow began to fall at this point, which stuck in my hair and coated my clothing. I gritted my teeth and ploughed on, telling myself I was very nearly there and to keep going. I was panting and breathless, and probably looked like a snowman when I finally reached Sarah’s door.

The relieved and grateful look on Robin’s face when he saw me standing there was one I had seen many times before. It didn’t matter a jot that I looked like a snowman. I was a midwife underneath the snowflakes, and that was all the expectant dad could see in that moment.

Thank goodness Sarah had not delivered the baby before I arrived. This was not an ideal scenario, as Sarah had wanted to give birth in hospital, but as a community midwife I was well used to walking into situations where you simply had to make the best of things.

‘Thank God,’ Sarah blurted as soon as she saw me. She was wrapped in a pink cotton dressing gown and lying uncomfortably on the bathmat.

An ambulanceman was standing by, hovering beside the bathroom door. ‘Well done. I think you’ve made it in the nick of time,’ he said quietly to me as I dashed in and knelt at Sarah’s side. As he spoke the patient let out a rip-roaring scream. ‘Jesus Christ! It’s killing me! Make it stop!’

I pulled on a pair of rubber gloves as hurriedly as I could, though my fingers were still numb with cold. ‘I’m going to have a little look,’ I told Sarah. ‘Just keep breathing and panting as you are, that’s good …’

‘Jesus! Your hands are freezing!’

‘I’m really sorry. But let’s see … oh, that’s good. You’ve done ever so well here.’

Water was trickling from my hair, leaving big wet blobs on Sarah’s dressing gown. ‘Sorry, again,’ I apologised, wiping my face with the back of my forearm.

Sarah was ready to push, and I tried to soothe her with this good news. ‘Just give me a moment while I get my instruments out. I’m going to tell you when to push, and I think your baby is going to be here very soon.’

‘Will you hurry up?!’ she said, which prompted her husband to let out an embarrassed laugh.

‘There we are. Give me a nice big push right on your next breath … I can see baby’s head. Lovely, lovely. You are doing really well …’

‘Jesus. Jesus,’ she cursed. Robin was holding one hand and Sarah thrashed about for something to grab hold of with the other. The nearest thing to hand was a toilet roll holder, which she squeezed for all it was worth.

Moments later I guided one small shoulder out, then the next. The atmosphere suddenly felt incredibly calm as the baby girl arrived very gracefully, slowly emerging into my hands. There was a brief moment of perfect silence in the room, and then the little girl let out a piercing cry. It was an absolutely beautiful delivery.

‘There’s nothing wrong with her lungs!’ Robin gasped with relief.

‘You can say that again. And she’s not crying because I have cold hands,’ I smiled. ‘I’ve warmed up a bit now!’

Sarah burst into tears when she took hold of her baby daughter. ‘Aren’t you just perfect?’ she told her. ‘You’re gorgeous!’

The new mum was propped up against the side of the bath by now, and someone had fetched a pillow for her to lean back on, but from the ecstatic expression on Sarah’s face, any thoughts of being uncomfortable on the bathroom floor were not important right now. I could see snow falling outside the bathroom window, and the scene before me of mother and daughter sharing their first precious moments warmed my heart. This really was what life is all about.

Later, Sarah, baby Kate and proud new dad Robin invited me to sit with them around a roaring fire they had going in the lounge, which was decked out with a beautiful Christmas tree that filled the room with the smell of fresh pine needles. Robin made me a steaming mug of hot chocolate and we sat there chatting while I dried my clothes out. At about 2.30 a.m., when I was satisfied Sarah and Kate were both well, Robin drove me back down the lane in his Range Rover and made sure I could drive away safely, which, thankfully, I could. I had been told that the second midwife dispatched to the address had not made it through the snow and had had to turn back, so I was very grateful for Robin’s help.

‘Don’t thank me,’ he said. ‘It’s Sarah and I who are very grateful to you. I don’t know what we would have done without you.’

I don’t remember the cold or the bleakness all around me on my slow journey home. I was just thrilled to have played a part in Kate’s safe arrival, and the adrenaline was still flowing through my body, all the way back to Mottram.

A decade on, I still have a very clear image in my mind of that brand new little family huddled together in front of the flickering fire. They looked a picture of happiness. Sarah’s cheeks were flushed pink and she had a wonderful glow about her. Robin was beaming so brightly he practically had sparks of pride bouncing off him, and little Kate looked blissfully content, wrapped in a beautiful white fleece blanket as she slept soundly in her mother’s arms.

It is one of the many births I will never forget in my forty-two years as a midwife. I have delivered more than 2,200 babies and I still have my heart in my mouth each and every time I report for duty. I never know what might take my breath away next, and that is why I continue to do the job I love.

Chapter One

‘I’d love to hear some good news’

‘Is there anything I can do to help, Nurse?

Mrs Sheridan’s well-fed son Simon was fast asleep in the plastic cot beside her bed, and she could see that I was run off my feet on the busy new postnatal ward.

‘Actually, yes, that’s very kind of you,’ I replied gratefully. ‘Would you mind wheeling Tina in her pram?’

Baby Tina was a fragile little girl who had been born small for dates and was always hungry, which made her unsettled.

‘It would be my pleasure,’ Mrs Sheridan beamed. ‘Poor little mite, I don’t mind one bit.’

Baby Tina’s mother was a seventeen-year-old girl who had decided to put her daughter up for adoption as soon as she was born. The young mother had discharged herself a few days earlier, leaving Tina in our care until the authorities were able to place her with a foster parent.

All the new mothers on this ward understood the situation, and a few had pitched in over the last day or two to give Tina a cuddle or a ride in her pram, whenever their own babies were sleeping soundly in their cots.

I directed Mrs Sheridan to the nursery, where Tina lay.

‘Call one of the other midwives if Simon wakes up and you need to leave Tina, if she is not settled.’

‘Don’t worry, Nurse,’ she smiled. ‘I can manage, no bother.’

It was Thursday 3 February 1972, and local dignitaries were gathered downstairs, in the entrance to Ashton General Hospital’s Maternity Unit, for the official opening ceremony. I had been told to try to attend the event, and so I slipped away, leaving the staff nurse in charge of the ward.

I quickly took the lift down to the ground floor, hoping to catch a glimpse of the historic moment when Sir John Peel, President of the International Federation of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, would unveil a plaque on the wall, declaring the unit officially open.

I was a junior sister now and, as I stood at the back of the foyer that day, I allowed myself a moment of reflection and self-congratulation. My husband Graham, proud as ever, had bought me an antique silver buckle to attach to my red belt. I now wore a navy blue dress instead of a pale blue one and I had the ‘frillies’ on the cuffs of my short sleeves.

In becoming a sister in January 1972, one year after qualifying as a staff midwife, I had reached another milestone in my career. I felt a great sense of achievement as I watched the brass plaque being unveiled and listened to a succession of local dignitaries applauding our new 142-bed, £2 million maternity unit.

Sir John spoke of the tremendous advances in obstetrics, and of how modern techniques had combated the once high mortality rate amongst newborns. The Department of Health had achieved its national target of ensuring 70 per cent of births took place in hospital, he said, and in the Manchester Hospital Region the figure exceeded 80 per cent. This meant that our new unit was much needed.

I smiled warmly as a beaming Mrs Randle, the mother of the first baby to be born in the new unit in December 1971, was presented with a silver cup while her son Jarrod slept in her arms, oblivious to his starring role in the proceedings. Lord Wright, Chairman of the Ashton and Hyde Hospital Management Committee, declared triumphantly: ‘We are proud of this unit and we should take pride in seeing the happy, smiling faces of the mothers in the unit!’ The local press turned out to cover the event and, as photographs were taken for posterity, I thought it was a day I would not forget.

Afterwards I returned to the postnatal ward with a real spring in my step. We had this whole five-storey unit all to ourselves, and I loved working in it. Gone were the days when the maternity unit was housed inside the old Ashton General Hospital. We still shared the same grounds, but now our new facility stood alone, a state-of-the-art 1970s steel-framed block, clad with contemporary concrete panels.

I’d excitedly watched the building work progress throughout 1970. I remembered peeping inside as the unit slowly began to take shape, excitedly imagining what it would be like to have ultra-modern plastic cots instead of old-fashioned cloth cribs, shiny store cupboards stocked with luxuries like disposable syringes and razors, and even paper caps and plastic aprons to replace our starched cotton ones. Now, I was actually working here – and as a junior ward sister, no less!

Stepping back inside the ward, I went straight over to Mrs Sheridan, who was rocking a very satisfied-looking Tina tenderly in her arms while her son Simon continued to sleep soundly in his cot. If Lord Wright were to walk in here now, I thought, he’d be delighted to see how well these new wards were working out, and he would indeed see the ‘happy, smiling faces’ he had talked so animatedly about. The atmosphere here was friendly, just as it was on the big open-plan Nightingale wards at the old maternity unit, yet there was a more intimate and peaceful feel to these smaller wards, too, as they were divided into rooms with four beds in each. I liked them very much.

‘Good. You managed to settle her?’ I said to Mrs Sheridan, who was looking very relaxed and had clearly had no trouble with either Tina or Simon.

‘She did ever so well,’ Mrs Sheridan replied, giving me a satisfied smile. ‘Hope you don’t mind, Nurse, but I gave her a little breastfeed.’

‘Pardon?’

‘Well, I knew it would be the only breastmilk she would ever get and I thought it would give her a good start. Simon’s doing so well on my milk that Sister Kelly said she thinks I must be producing Gold Top!’

I gasped, feeling absolutely flabbergasted. Breastfeeding had gone out of fashion at the time, and was nowhere near as common as it is today – in fact, midwives had a job convincing most women of its benefits. The majority of women still asked for a course of Stilboestrol, prescribed to suppress their milk, and most opted to bottle-feed from day one. Mrs Sheridan was clearly not one of those women – far from it!

‘Well, you’ve obviously done a very good job,’ I said tactfully, taking a deep breath and lifting the contented baby girl out of her arms, my brain going into overdrive as I wondered how I was going to handle this one.

At that precise moment some of the dignitaries from the opening ceremony appeared in the corridor outside the ward. Miss Sefton, Head of Midwifery, stood in the doorway and began enthusing loudly about the marvellous new facilities.

‘Most of the accommodation is in four-bedded rooms which combine sociability with quietness,’ I heard her say. ‘And I am very pleased to say that the new unit is attracting the highest calibre of midwives. We are very proud of our staff – in fact Sister Buckley over there is the very midwife you may have seen on the posters advertising the new unit across the region …’

I took a deep breath and smiled over at them. I was normally very proud of the fact I was indeed the midwife who had been chosen to promote the new unit, and had had my photograph plastered all over Ashton and its surrounding area in the previous few months.

At that moment, however, I wanted the ground to swallow me up, and I was willing the entourage not to come any closer.

I can’t describe how relieved I was when the assorted ladies and gentlemen smiled back approvingly and then continued their tour, walking away from me, down the corridor.

‘Well, Mrs Sheridan,’ I whispered, trying hard not to appear as flustered as I felt. ‘Of course it’s not really the done thing to breastfeed another woman’s baby, but I know you have done it with the best of intentions. I shall have to tell Sister Kelly what you’ve done, though, I’m sure you’ll understand.’

‘I don’t mind one bit,’ she replied. ‘Why would I?’

I look back today and am still flabbergasted; not simply by what Mrs Sheridan actually did, but by how much society has changed.

Nowadays, of course, no woman would dream of breastfeeding someone else’s child like that. If she did, it wouldn’t just be a question of informing the senior sister on the ward, who would most certainly not react in the way Sister Kelly did that day, which was to simply roll her eyes and say, ‘I’ll make a note, but there’s no harm done, is there now?’

Blood tests would have to be carried out to make sure the baby had not been infected in any way, and the threat of legal action would be very real, but back then HIV was unheard of, and litigation was a word we rarely heard.

That said, what happened with Mrs Sheridan also reminds me how very little things have changed over the years. Mothers, and the depths of their maternal instincts, have never stopped amazing me, from that day to this.

About a month later, in March 1972, I was working a shift in the antenatal clinic when I saw a name I recognised – Mrs Sully – on my list. My gut reaction was that I was delighted to see this lady was pregnant again. In her case, I imagined those deep maternal instincts must have given her the strength and courage needed to try again, as she had lost her first baby in dreadful circumstances the previous summer.

I would never forget her arriving at the labour ward in the old hospital, brimming with hope and excitement, as she did throughout her pregnancy. I vividly remembered how everything had seemed so normal, until the awful moment I realised her baby’s umbilical cord had prolapsed.

‘There’s something between my legs,’ Mrs Sully had announced, setting off a heart-breaking chain of events. I had ridden beside Mrs Sully on the trolley as we dashed to theatre for an emergency Caesarean. I could see myself struggling to hold the baby’s head back inside her, desperately trying to stop it crushing the escaped cord, which was hanging outside of the poor lady’s body. I recalled seeing Mrs Sully struggling, too. She was thrashing about on the theatre bed instead of falling quickly asleep under the anaesthetic as we needed her to, in order for the surgeon to perform the Caesarean as quickly as possible.

I remembered the absolute chill that went through my body when I realised that Mrs Sully’s baby son was born too late. He survived for just fifteen minutes, having been starved of oxygen in the womb. It was nobody’s fault, just one of those exceptionally cruel twists of fate that occur so rarely, yet prompt you to wonder if there really is a God.

‘I want a hatful of kids, I do,’ Mrs Sully had said to me this time last year, the very first time I had met her in the old antenatal clinic.

I had hoped and prayed that her wish would still come true despite her dreadful loss, and somehow I believed it would.

‘Good morning, Nurse!’ she smiled at me today.

I was delighted to see that the roses Mrs Sully had had in her cheeks when I first met her had returned. She was blooming again, cradling her tiny bump and looking as pleased as punch to be pregnant once more.

‘Good morning, Mrs Sully,’ I grinned back.

I was so relieved that she was still the positive and optimistic person I remembered. There was clearly no need for me to be apprehensive about seeing her again. Some women may have been reluctant – superstitious, even – to see the same midwife, but not Mrs Sully.

‘I’m glad it’s you,’ she sighed, looking quite relieved. ‘I was worried I might have to talk about what happened, go through everything again …’

I gave a little sigh of relief, too. As a midwife, if anything has not gone to plan, it’s always a great comfort to know that the mother understands it was not your fault. Midwives are not miracle workers; we can only ever do our very best in the circumstances, and sometimes, sadly, that is just not good enough. Therefore, I was very glad to see that Mrs Sully was as happy to see me as I was to see her.

I examined Mrs Sully by palpating her abdomen and listening to her baby’s heartbeat with a Pinard’s stethoscope. Everything seemed in perfect order, and I was pleased to note that she was approximately sixteen weeks pregnant and her baby was due in late August. I was absolutely delighted for her; she certainly deserved some good fortune.

‘That day,’ she said wistfully. ‘That day, I could never have imagined ever feeling happy again. Now it seems such a long time ago.’

‘Doesn’t it just,’ I said, and we smiled at each other.

I had turned twenty-four a few days earlier, on 22 March 1972, and I felt more confident and self-assured than ever in my job. Being a ward sister made me walk just that little bit taller. It seemed such a long time ago that I had begun my training as a pupil midwife at Ashton General after three years of nurses’ training at the Manchester Royal Infirmary. In fact it was just two years on, but so much had happened during my time as a midwife.

I remembered wondering, back in 1970, how I was going to manage to deliver forty babies – the required number for me to complete my ten-month training and qualify as a staff midwife. It had seemed such a huge number, but now it seemed so few.

In my first two years I had delivered over a hundred babies, and this new maternity unit seemed to be getting busier by the day as the Government continued to encourage women to have hospital births, believing them to be safer.

‘I don’t know about all this hospital birth business,’ Mrs Tattersall, my community midwife mentor, had said to me on more than one occasion when I was learning the ropes from her as a pupil midwife out in the district.

‘If you ask me, the best tools a midwife has are her hands. They’re the same tools midwives have used since biblical times, and I have always thought you can’t beat them.’

‘Yes, Mrs Tattersall,’ I agreed with her. ‘But then again it’s reassuring to have the paediatricians and doctors, and the theatre on hand if need be, sometimes.’

‘Granted, Linda,’ she said. ‘But a good community midwife should be able to assess when a home birth is not a safe option. Look at it like this. If you give birth at home, there’s a good chance you’ll have two midwives attending – the community midwife and a pupil midwife. What happens in hospital? Tell me that? The place is always bursting at the seams, with one poor midwife trying to look after four or five labouring women all at the same time. Where’s the sense in that? If you’ve got no complications, I can’t see why any woman would choose to be stuck in hospital. That’s a complication in itself, if you ask me.’

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.