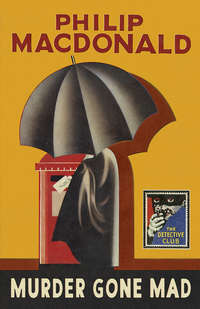

Buch lesen: "Murder Gone Mad"

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published for The Crime Club by W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1931

Copyright © Estate of Philip MacDonald 1931

Introduction © L. C. Tyler 2017

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008216351

Ebook Edition © December 2016 ISBN: 9780008216368

Version: 2016-11-23

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Footnote

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTIONS, like prologues, are often best skipped. They are not, after all, what you have bought the book for and few good stories really need an explanation.

And yet, readers of this volume may welcome a short account of Philip MacDonald and his work, if only because after his death in 1980 his books quickly slipped from public view and information on him can be surprisingly difficult to find and sometimes contradictory. Even the year of MacDonald’s birth has for some reason become veiled in mystery. 1896, 1899, 1900 and 1901 are all quoted by reliable sources.

The question of his birth can be quickly cleared up. Census records show that he was born on 5 November 1900 into a family that was very much part of the British literary establishment. His grandfather was the Scottish novelist and poet, George MacDonald, whose pioneering fantasy writing influenced many other writers, including J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and indeed G.K. Chesterton. His father was the playwright and novelist Ronald MacDonald and his mother the actress Constance Robertson. At the time of his birth the family was living (with one servant) at 9 Rossetti Mansions, Chelsea. Later they moved (gaining an additional servant on the way) to 25 St Margaret’s Road, Twickenham, from where MacDonald attended St Paul’s School. During the First World War, he served in Mesopotamia, though again details are hard to come by. His publisher after the war claimed he had served as a trooper in a ‘famous cavalry regiment’ but never thought to say which one and, to the best of my knowledge, nobody has subsequently identified it for certain. (It may have been the Machine Gun Corps Cavalry.) Whichever regiment it was, and whatever action he saw, MacDonald made good use of his experience in one of his earliest novels, Patrol (1927), in which a cavalry troop finds itself lost in the desert. It is told very much from the point of view of the ordinary soldier—the only officer is already dead at the start of the tale, having failed to impart to his second-in-command their current location or the object of the mission. Only the bravery and common sense of the troopers can see them through to possible safety—it is apparent where in the military hierarchy MacDonald’s sympathies lay.

His earliest publication was the perhaps unfortunately named Ambrotox and Limping Dick (1920), written jointly with his father under the pen name Oliver Fleming. He would later write variously as Anthony Lawless, Martin Porlock, W.J. Stewart and Warren Stewart. The first book under his own name however was The Rasp, which was published by Collins in 1924 and introduced his main series protagonist, gentleman detective and scholar Colonel Anthony Ruthven Gethryn. The Rasp was an immediate success and was later made into a film. Other crime novels followed in rapid succession. In 1931 MacDonald published no fewer than seven: four under his own name, two as Lawless and one as Porlock. In the same year he moved to Hollywood with his new wife, the author F. Ruth Howard, and started a career as a screenwriter, both adapting his own work and writing original film scripts. These last included contributions to popular series such as Charlie Chan and Mr Moto. He also adapted Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca and Agatha Christie’s short story ‘Philomel Cottage’ (as Love from a Stranger).

Though MacDonald maintained the flow of crime fiction novels during the 1930s, film work and later television increasingly dominated his output. He did however win two Edgar Allan Poe Awards for his short stories in the ’50s and his final Gethryn novel, The List of Adrian Messenger, published in 1959, is arguably the finest that he ever wrote.

What characterises MacDonald’s output, in addition to the remarkable speed with which he produced it, is its inventiveness. At the same time that Agatha Christie was experimenting with storyline, producing one classic plot after another, MacDonald was consciously experimenting with the form of the detective novel. The Maze (1932), another of his best works, dispenses with a detective almost completely. The reader is presented with transcripts of the evidence given by witnesses at a coroner’s court. Only at the very end does Anthony Gethryn appear to confirm or refute the reader’s solution. Rynox (1930) begins with an epilogue, ends with a prologue and is interrupted by a series of sardonic comments from the author—MacDonald acting as a sort of Greek chorus in his own book, foreshadowing future developments. ‘All is not well’ we are told ‘with RYNOX. RYNOX is at that point where one injudicious move, one failure of judgment, one coincidental piece of bad luck will wreck it …’ Like most Greek choruses, he’s spot on. There is a metafictional side to his work as well. Having, in another book, discovered a body in the study, Gethryn remarks to the policeman: ‘Ever read detective stories, Boyd? They’re always killed in their studies. Always! Ever notice that?’ MacDonald also uses humour well and produces some lovely quotable lines. One of my favourites (from Adrian Messenger) is: ‘That winter, like all California winters, was unusual.’

The other side of the coin of this remarkable flow of witty and innovative books was however a tendency to ignore detail in a way that less brilliant, more conventional writers would never have dared to do. Julian Symons described MacDonald as ‘a restless but careless experimenter’. There are times when you feel that MacDonald is so caught up in his own cleverness that he misses, or can’t be bothered with, the obvious. On at least one occasion the reader is left wondering why it didn’t occur to the police to look for fingerprints, which would have shortened their investigations by a couple of hundred pages. But the pace is such that it probably doesn’t occur to the reader either until long after they have finished the book.

Murder Gone Mad, the third of MacDonald’s books to be republished in this series, encapsulates many of the strengths outlined above. It is one of the earliest books to make use of the serial killer. (It also incidentally anticipates the invention of CCTV as a means of detecting crime.) It works splendidly as a ‘fair play’ detective story. But at the same time it is a very clever satire on the British class system. Holmdale, the scene of the murders, is a new town, painfully conscious of its image. It does not like to be referred to as ‘Holmdale Garden City’, with the lower middle class undertones that the name carries, and certainly does not like the bad publicity created by a series of grizzly murders. The killer seems determined to lower the tone of things still further, their invoice-like communications to the police, one following each killing, smacking very much of ‘trade’:

My Reference ONE

R.I.P.

Lionel Frederick Colby,

died Friday 23rd November

THE BUTCHER

When a report is produced by the police examining the murders to date, the victims are listed under ‘clerical class’, ‘leisured class’, ‘labouring class’ and ‘skilled workman class’—a fairly nuanced series of distinctions. But, the police report concludes, the murderer ‘must belong to the clerical or governing class’ to have the opportunity to mix with all classes of the community—a member of the working classes simply wouldn’t have the contacts. When Dr Reade is suspected, somebody who knows him protests: ‘Blasted rot, my dear fellow! What I mean: a chap, a decent chap like Reade, the sort of chap who’s always good for a hand of Bridge and that sort of thing; the sort of chap one has dinner with and all that … he can’t possibly be this Butcher.’ But, of course, we all know that he or any of the citizens of Holmdale could be the killer. MacDonald also anticipates Nancy Mitford’s popularisation of U and non-U language by putting the word ‘lounge’ firmly in quotation marks.

All classes are however united in their horror at the unremitting succession of killings. ‘Is our city to be another Düsseldorf?’ asks the local paper, somewhat enigmatically—not just lower middle class then but, worse still, German?

The Düsseldorf references are almost certainly inspired by the case of Peter Kürten, the so-called Vampire of Düsseldorf or Düsseldorf Monster, who during the 1920s murdered at least nine people, mainly (like The Butcher) by stabbing, and who was executed the year Murder Gone Mad was published. It took the German police over a year to catch him—something that does not impress the British officers seeking the Holmdale murderer, though initially they do little better than their Düsseldorf counterparts—perhaps because Gethryn is, we learn, injured and unavailable. This time it is Superintendent Arnold Pike, a character from earlier books, who leads the investigation and eventually makes the arrest under what prove to be trying circumstances. Thus it all ends in precisely the way a detective story is supposed to end, with the reader having been given a fair chance to guess which suspect Pike will apprehend at the conclusion.

Murder Gone Mad, originally published in MacDonald’s annus mirabilis of 1931, is one of his most successful, most satisfying books. John Dickson Carr listed it as one of the ten best detective novels ever written. Its reprinting in the revived Detective Club series will hopefully introduce it to a new generation of crime fans and help re-establish MacDonald’s reputation as one of the most original and most readable writers of the Golden Age.

L.C. TYLER

September 2016

CHAPTER I

I

THERE had been a fall of snow in the afternoon. A light, white mantle still covered the fields upon either side of the line. The gaunt hedges which crowned the walls of the cutting before Holmdale station were traceries of white and black.

The station-master came out on to the platform from his little overheated room. He shivered and blew upon his hands. The ringing click-clock of the ‘down’ signal arm dropping came hard to his ears on the cold air.

‘Harris!’ called the station-master. ‘Six-thirty’s coming!’

A porter came out from behind the bookstall. He was thrusting behind a large and crimson ear a recently pinched-out end of a cigarette.

The six-thirty came in with much hissing of steam and a whistling grind of brakes. The six-thirty reached the whole length of Holmdale’s long platform. The six-thirty looked like a row of gaily-lighted, densely-populated little houses. The six-thirty’s engine, for some reason known only to itself and its attendants, let off steam in a continuous and teeth-grating shriek. The doors of the six-thirty all along the six-thirty’s flank began to swing open. Holmdale was the six-thirty’s first stop since leaving St Pancras, now forty miles and forty-five minutes behind it.

The station-master stood by the foot of the steps leading up to the bridge. He opened a square and bearded mouth and chanted his nightly chant, quite unintelligibly, of what was going to happen to the train. He should properly have walked up and down the train with his chant, but he knew only too well that to walk at all against this tide which now covered the platform like a moving carpet of black, huge locusts, was impossible.

The six-thirty’s engine ceased its hissing. There was a great slamming of doors which sounded under the station’s iron roof like big guns heard in the distance. There were indistinguishable cries from one end of the train to the other. The guard held up his lantern, green-shaded. The six-thirty settled down to her work. The little lighted houses, most of them now untenanted, began once more their rolling march … The six-thirty was gone.

But, as yet, only the very first trickles of the black flood were over the bridge and outside Holmdale station. They were so tight packed, the units which went to the making of this flood, that speed, however passionately each unit undoubtedly desired it, was impossible. They surged up the stairs. At the head of the stairs they split into two streams, one flowing right and east and the other left and west. Two streams flowed across the bridge and down other stairs. At the foot of each staircase stood a harassed porter snatching such tickets as offered themselves and glancing, like a distracted nursemaid, at hundreds of green, square pieces of pasteboard marked ‘Season’.

The left-hand staircase leads into the main booking hall of Holmdale station and this hall is lighted. As the flood, after the first trickling, really surges into the hall, it is possible for the first time fully to realise that not only are the component parts of the flood human, but that these humans are not uniform. Look, and you will see that there are women where at first you would have been prepared to take oath that there had been nothing save men. Look again, and you will see that all the hats are not, as you first supposed, bowler hats and from the same mould, but that every here and there a rebellious head flaunts cap or soft hat. Look again, and you will see that the men and the women are of different height, different feature and perhaps, even, different habit. But you will look in vain for man or woman who does not carry a small, square, flat case.

The flood pours through the booking hall and out through the double doors into the clear, cold night. In the gravelled, white-fenced, semi-circular forecourt to the station, wait, softly chugging, two bright-lighted omnibuses looking like distorted caravans. Each of these omnibuses is meant to hold—as he who peers may read—twenty-seven passengers. Each, not less than two minutes after the flood has begun to break about their wheels, grinds off through the night with fifty at least. The rest of the flood, thinning gradually into trickles and then, at last, into units, goes off walking and talking. Their voices carry a little shrill on the cold, dark air and the sound of their boot-soles rings on the smooth iron road. Between the forecourt and the station is a dark expanse edged at its far sides by little squares of yellow light where the houses begin.

II

‘Coo!’ said Mr Colby. ‘Sorry we couldn’t get the bus, ol’ man!’

‘Not a bit. Not a bit,’ mumbled Mr Colby’s friend, turning up the rather worn velvet collar of his black coat.

‘Not,’ said Mr Colby, ‘that I mind myself. Personally, Harvey, I rather look forward to a nice, crisp trudge. Seems somehow to blow away the cobwebs.’

‘Yes,’ said Mr Harvey. ‘Quite.’

Mr Colby, having shifted his umbrella and attaché-case to his right hand, took Mr Harvey’s arm with his left.

‘It’s only a matter,’ said Mr Colby, ‘of a mile and a bit. Give us all the more appetite for our supper, eh?’

‘Quite,’ said Mr Harvey.

‘I wish,’ said Mr Colby, ‘that it wasn’t so dark. I’d have liked you to have seen the place a bit. However, you will tomorrow morning.’

Mr Harvey grunted.

‘There are two ways to get to my little place,’ said Mr Colby. ‘One’s across the fields and the other’s up here through Collingwood Road. Personally, I always go over the fields but I think we’ll go by Collingwood Road tonight. The field’s a bit rough for a stranger if he doesn’t know the ground.’ Mr Colby broke off to sniff the cold air with much and rather noisy appreciation. ‘Marvellously bracing air here,’ said he. ‘Didn’t you feel it as you got out of the train? You know we’re nearly five hundred feet up and really right in the middle of the country. Yes, Harvey, five hundred feet!’

‘Is that,’ said Mr Harvey, ‘so?’

‘Yes, five hundred feet. Why, since we’ve been here, my boy’s a different lad. When we came, a year ago, his mother—and his old dad too, I can tell you—were very worried about Lionel. You know what I mean, Harvey, he was sort of sickly and a bit undersized and now he’s a great big lad. Well, you’ll see him yourself … Here we are at Collingwood Road.’

‘Collingwood Road, eh?’ said Mr Harvey.

Mr Colby nodded emphatically. In the darkness, his round, bowler-hatted head looked like a goblin’s.

‘We don’t live in Collingwood Road, of course. We’re right at the other side of the place. More on the edge of the country. Our bedroom and the room you’re sleeping in tonight, ol’ man, look out right across the fields and woods. In the spring, as Mrs Colby was saying to me only the other day, it’s as pretty as a picture.’

Mr Harvey unburdened himself of a remark. ‘A good idea,’ said Mr Harvey approvingly, ‘these Garden Cities.’

‘Holmdale,’ said Mr Colby with some sternness, ‘is not a Garden City. You don’t find any long-haired artists and such in Holmdale. Not, of course, that we don’t have a lot of journalists and authors live here, but if you see what I mean, they’re not the cranky sort. People don’t walk about in bath-gowns and slippers the way I’ve seen them at Letchworth. No, sir, Holmdale is Holmdale.’

Perhaps the unwonted exercise—they were walking at nearly four miles an hour—coupled with the cold and bracing air of Holmdale—had induced an unusual belligerence in Mr Harvey. ‘I always understood,’ said Mr Harvey argumentatively, ‘that the place’s name was Holmdale Garden City.’

‘When you said was,’ said Mr Colby, ‘you are right. The place’s name is Holmdale, Harvey. Holmdale pure and Holmdale simple. At the semi-annual general meeting of the shareholders—Mrs Colby and I have got a bit tucked away in this and go to all the meetings—the one held last July, it was decided that the words Garden City should be done away with. I supported the motion strongly; very, very strongly! And fortunately it was carried.’ Mr Colby laughed a reassuring, friendly laugh and once more put his left hand upon Mr Harvey’s right arm. ‘So you see, Harvey,’ said Mr Colby, ‘that if you want to get on in Holmdale you mustn’t call it Holmdale Garden City.’

‘I see,’ said Mr Harvey. ‘Quite.’

They were now at the end of Collingwood Road—a long sweep, flanked by small, neat, undivided gardens and small, neat-seeming, shadowy houses. Beneath a street lamp—a curious and most ingeniously un-street-lamplike lamp—which was only the third that they had passed in the whole of their three-quarter mile walk, Mr Colby stopped to look at his watch.

‘Very good time,’ said Mr Colby. ‘Harvey, you’re a bit of a walker! I always take my time here and I find I’ve beaten last night’s walk by fully half a minute. Now we haven’t far to go. We shall soon be toasting our toes and perhaps having a drop of something.’

‘That,’ said Mr Harvey warmly, ‘will be very nice.’

They crossed the narrow, suddenly rural width of Marrowbone Lane and so came to the beginning of Heathcote Rise.

‘At the top here,’ said Mr Colby, ‘we turn off to the right and then we’re home.’

‘Ah!’ said Mr Harvey.

‘The only thing about this walk,’ said Mr Colby glancing about him in the darkness with the air of one who knows the place so well that clear vision is not required, ‘the only thing about this walk that I don’t like, is this bit. Of course you can’t see it, Harvey, but I assure you Heathcote Rise isn’t—well—isn’t, as you might say, worthy of the rest of Holmdale. I don’t think anyone could call me snobbish, but I must say that I think it rather extraordinary of the authorities to let this row of labourers’ cottages go up here. They ought to have kept that sort of thing for The Other Side.’

‘The other side,’ said Mr Harvey, ‘of what?’

‘The railway, of course,’ said Mr Colby. ‘You see, the idea is to have what you might call an industrial quarter one side of the railway and a—well—a superior residential quarter on this side of the railway. Very good notion, don’t you think, ol’ man?’

‘Splendid!’ said Mr Harvey.

‘Round here. Round here,’ Mr Colby, with increasing jocularity, swung Mr Harvey to his left. They entered the dark and box-hedged mouth of what seemed to be a narrow passage. They came out after ten yards of this into a small rectangle. So far as Mr Harvey was able to see, this rectangle was composed of small and uniform houses all ‘attached’ and all looking out upon a lawn dotted with raised flower beds. Round the lawn were small white posts having a small white chain swung between them. All the square ground-floor windows showed pinkly glowing lights. Mr Harvey wondered for a moment whether all the housewives of The Keep—he knew his friend’s address to be No. 4, The Keep—had chosen their curtains together.

‘Here we are! Here we are! Here we are!’ said Mr Colby in a sudden orgy of exuberance. He had stopped before a small and crimson door over which hung by a bracket a very shiny brass lantern. He released the arm of Mr Harvey and fumbled for his key chain, but before the keys were out the small red door opened.

‘Come in, do!’ said Mrs Colby. ‘You must both be starved!’

They came in. The small hall was suddenly packed with human bodies.

‘This,’ said Mr Colby looking at his wife and somehow edging clear, ‘is Mr Harvey. Harvey, this is Mrs Colby.’

‘Very pleased,’ said Mr Harvey, ‘to meet you.’

‘So am I, I’m sure,’ said Mrs Colby. She was a plump and pleasant and bustling little person who yet gave an impression of placidity. Her age might have been anywhere between twenty-eight and forty. She was pretty and had been prettier. She stood looking from her husband to her husband’s friend and back again.

Mr Colby, whose christian name was George, was forty-five years of age, five feet five and a half inches in height, forty-one and a half inches round the belly and weighed approximately ten stone and seven pounds. He had pleasing and kindly blue eyes, a good forehead and a moustache which seemed, although really it was not out of hand, too big for his face.

Mr Harvey was forty years old, six feet two inches in height, thirty inches round the chest and weighed, stripped, nine stone and eleven pounds. Mr Harvey was clean-shaven. He was also bald. His face, at first sight rather a stern, harsh, hatchet-like face, was furrowed with a myopic frown and two deep-graven lines running from the base of his nose to the corners of his mouth. When Mr Harvey smiled, however, which was quite frequently, one saw, as just now Mrs Colby had seen, that he was a man as pleasant and even milder natured than his host.

‘This,’ said Mr Colby throwing open the second door in the right-hand wall, ‘is the sitting-room. Come in, Harvey, ol’ man.’

Mr Harvey squeezed his narrowness first past his hostess and then his host.

‘You coming in, dear?’ said Mr Colby.

His wife shook her head. ‘Not just now, father. I must help Rose with the supper.’

‘Where’s the boy?’ said Mr Colby.

‘Upstairs,’ said the boy’s mother, ‘finishing his home lessons. It’s the Boys’ Club Meeting after supper and he wants to get the work done first.’

‘If we might,’ said Mr Colby with something of an air, ‘have a couple of glasses …’

Mrs Colby bustled away. Mr Colby went into the sitting-room with his friend. Mr Colby impressively opened a cupboard in the bottom of the writing desk and took from the cupboard a black bottle and a syphon of soda water. Mrs Colby entered with a tray upon which were two tumblers. She set the tray down upon the side table. She raised the forefinger of her right hand; shook it once in the direction of her husband and once, a little less roguishly, at Mr Harvey.

‘You men!’ said Mrs Colby.

Mr Colby and his guest lay back in their chairs, their feet stretched before the fire. In each man’s hand was a tumbler. They were very comfortable, a little pompous and entirely happy. To them, when the glasses were nearly empty, entered Master Lionel Colby; a boy of eleven years, well-built and holding himself well; a boy with an engaging round face and slightly mischievous, wondering blue eyes which looked straight into the eyes of anyone to whom he spoke. Lionel obviously combined in his person, and also probably in his mind, the best qualities of his parents. He shook hands politely with Mr Harvey. He reported, with some camaraderie but equal politeness, his day’s doings to his father.

‘Homework done?’ said Mr Colby.

Lionel shook his head. ‘Not quite all, daddy. I came down because mother told me to come and say how-do-you-do to Mr Harvey.’

Mr Colby surveyed his son with pride. ‘Better run up and finish it, son. Then come down again. What are you going to do at the Boys’ Club tonight?’

The round cheeks of Lionel flushed slightly. Lionel’s blue eyes glistened. ‘Boxing,’ said Lionel.

The door closed gently behind Lionel.

‘That,’ said Mr Harvey with genuine feeling, ‘is a fine boy, Colby!’

Mr Colby made those stammering, slightly throaty noises which are the middle-class Englishman’s way when praised for some quality or property of his own.

‘A fine boy!’ said Mr Harvey again.

‘A good enough lad,’ said Mr Colby. His tone was almost offensively casual. ‘Did I happen to tell you, Harvey, that he was top of his class for the last three terms and that the headmaster, Dr Farrow, told me himself that Lionel is one of the best scholars he’d had in the last twenty years? Not, mind you, Harvey, that he isn’t good at games. He’s captain of the second eleven and they tell me he’s going to be a very good boxer. I must say—although it isn’t really for me to say it—that a better, quieter, more loving lad it’d be difficult to find in the length and breadth of Holmdale.’

‘A fine boy!’ said Mr Harvey once more.

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.