Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "I Am Heathcliff: Stories Inspired by Wuthering Heights"

Copyright

The Borough Press

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

In the compilation and introductory material © Kate Mosse 2018

Terminus © Louise Doughty; Anima © Grace McCleen; A Bird, Half-Eaten © Nikesh Shukla; Thicker Than Blood © Erin Kelly; One Letter Different © Joanna Cannon; The Howling Girl © Laurie Penny; Five Sites, Five Stages © Lisa McInerney; Kit © Juno Dawson; My Eye Is a Button on Your Dress © Hanan al-Shaykh; The Cord © Alison Case; Heathcliffs I Have Known © Louisa Young; Amulet and Feathers © Leila Aboulela; How Things Disappear © Anna James; The Wildflowers © Dorothy Koomson; Heathcliff Is Not My Name © Michael Stewart; Only Joseph © Sophie Hannah

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

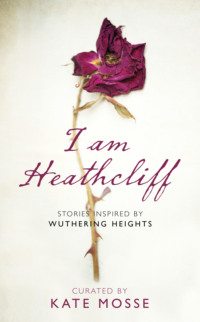

Jacket design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Jacket photographs © Sally Mundy/Trevillion Images, © Shutterstock.com petals

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

These stories are entirely works of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in them, while at times based on historical events and figures, are the works of the authors’ imaginations.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008257439

Ebook Edition © July 2018 ISBN: 9780008257453

Version: 2018-06-25

Dedication

For EB, in whose

footsteps we walk

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword by Kate Mosse

Terminus – Louise Doughty

Anima – Grace McCleen

A Bird, Half-Eaten – Nikesh Shukla

Thicker Than Blood – Erin Kelly

One Letter Different – Joanna Cannon

The Howling Girl – Laurie Penny

Five Sites, Five Stages – Lisa McInerney

Kit – Juno Dawson

My Eye Is a Button on Your Dress – Hanan al-Shaykh

The Cord – Alison Case

Heathcliffs I Have Known – Louisa Young

Amulet and Feathers – Leila Aboulela

How Things Disappear – Anna James

The Wildflowers – Dorothy Koomson

Heathcliff Is Not My Name – Michael Stewart

Only Joseph – Sophie Hannah

Footnotes

Notes on the Contributors

A Note on Emily Brontë

About the Publisher

FOREWORD BY KATE MOSSE

‘My love for Linton is like the foliage in the woods: time will change it, I’m well aware, as winter changes the trees. My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath: a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I am Heathcliff! He’s always, always in my mind: not as a pleasure, any more than I am always a pleasure to myself, but as my own being.’

THERE IS A HANDFUL of books that exist beyond their time and space, beyond the circumstances of their invention: novels that are significant, novels that are beloved. Familiar friends. Their characters step off the pages of the novel and into the real world, into a public conscience to be used ever after as shorthand for a certain sort of person. Archetypes, I suppose. Stories that seem bigger than the books that contain them. Wuthering Heights is such a book. Cathy and Heathcliff are such characters.

Published in 1847, Wuthering Heights is a novel that changes its character and colour with every reading, yet remains uniquely and absolutely itself. It is variously a Gothic novel of obsession and revenge; a story of ghosts and bad dreams; a novel of opposites – light and shade, wild Nature versus taming civilisation, storm versus calm, violence versus tenderness, revenge versus forgiveness, the North versus the South; a novel of race and class, of the powerlessness of women’s and children’s lives; a novel about poverty, property, and wealth; a novel about how the sins of the fathers (and dead or powerless mothers) are visited on the next generation; a story of two houses – Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange – on the Yorkshire Moors; a story of the shifting of time and how the land goes about its business indifferent to human emotions; a novel of order and disorder; of violence and the consequences of violence, of hate and the consequences of hate. Most of all, of course, it is held up as the most epic of love stories. But is it? It is a novel of obsession and all-devouring emotion, certainly, and about the nature and endurance of love, but romance it is not.

The telling of the story is complicated, and, though any reader picking up this collection will know the bare bones of it, it’s worth spending a moment thinking about the architecture of the novel. Wuthering Heights starts at the end – in 1801 – when a southern gentleman, Lockwood, calls upon his landlord and ‘solitary neighbour’, Heathcliff. The old farmhouse, Wuthering Heights, sits isolated and exposed to all elements of wind and weather, in sharp contrast to the comfortable, well-appointed Thrushcross Grange where Lockwood has come to recover from an unsuccessful love affair. Confused by the household he finds at Wuthering Heights on his first visit, he is drawn back. Trapped by a snowstorm, and obliged to stay the night, he finds a sequence of names – Catherine Earnshaw, Catherine Heathcliff, Catherine Linton – scratched into the paint of the windowsill. When he falls into uneasy sleep, his dreams are haunted by the ghost of Cathy trying to get in at the window. In one of the most violent scenes in the novel, Lockwood drags her white wrist across the broken glass to force her to let him go. Heathcliff distraught and wild and desperate into the chamber.

This is the brilliant framing device that whets the reader’s appetite and sets the narrative in motion.

When Lockwood returns to Thrushcross Grange the following morning, his head full of questions, he persuades the housekeeper, Ellen – Nelly – Dean, to tell him the story of Heathcliff and Catherine Earnshaw. Explain the connection between the two houses and families, going back a generation, Nelly speaks of the ‘dirty, ragged, black-haired child’ brought into the Earnshaw household and given the name Heathcliff; of the six-year-old Cathy and her jealous, bullying brother Hindley, of the growing affection between Cathy and Heathcliff, and of the very different household of Edgar Linton and his sister Isabella at Thrushcross Grange.

The fragment of dialogue from Chapter IX between Cathy and Nelly Dean quoted above – and which gives our collection its title – is at the heart of the novel. For Wuthering Heights is not a love story as we know it – or certainly as Victorian readers might have considered it – but rather a novel about the nature of love, of what happens when love is thwarted or distorted or traduced, of what happens when like and unalike come together. Cathy is thinking aloud, imagining herself married to either Edgar or to Heathcliff, in the same way she once scratched the three different names – the versions of herself – on the painted sill of her window at Wuthering Heights. Heathcliff overhears only the first part of her statement – that it would degrade her to marry him – and storms away devastated, so does not hear the second and most fundamental part of what Cathy believes.

He does not hear her say: ‘Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same.’ He does not hear her say that she loves him.

Heathcliff is gone for years, and, when he returns a wealthy man, is governed by revenge rather than love. He has killed the best part of himself, the part of himself that is Cathy. Tenderness is gone, leaving only cold self-interest. He finds Cathy married to Edgar Linton, and, in spite, marries Isabella. The first part of Wuthering Heights ends with the death of Cathy, having given birth to a daughter, and Heathcliff’s grief at losing her for ever.

The story of the second generation – the children of Heathcliff and Cathy – is less well known (and, in adaptations, often ignored altogether), but it is what gives the novel its unity, its balance. Heathcliff mourns Cathy, yet plots against her daughter. It is not until he abandons hate and only love remains, that they can be reconciled. Finally, the line between the living and the dead is blurred, and all that remains is peace. It is left to Nelly Dean, when Lockwood returns to Yorkshire in 1802, to recount the story of Heathcliff’s recent death, and bring the novel to a close. The final words are given – as are the first – to the outsider narrator, Lockwood, as he looks down upon the three headstones on the ‘slope next the Moor’: Cathy’s is ‘grey, and half buried in heath’; Edgar Linton’s is ‘only harmonised by the turf and moss creeping up its foot’; Heathcliff’s is ‘still bare’.

So, what makes Wuthering Heights – published the year before Emily Brontë’s own death – the powerful, enduring, exceptional novel it is? Is it a matter of character and sense of place? Depth of emotion or the beauty of her language? Epic and Gothic? Yes, but also because it is ambitious and uncompromising. Like many others, I have gone back to it in each decade of my life and found it subtly different each time. In my teens, I was swept away by the promise of a love story, though the anger and the violence and the pain were troubling to me. In my twenties, it was the history and the snapshot of social expectations that interested me. In my thirties, when I was starting to write fiction myself, I was gripped by the architecture of the novel – two narrators, two distinct periods of history and storytelling, the complicated switching of voice. In my forties, it was the colour and the texture, the Gothic spirit of place, the characterisation of Nature itself as sentient, violent, to be feared. Now, in my fifties, as well as all this, it is also the understanding of how utterly EB changed the rules of what was acceptable for a woman to write, and how we are all in her debt. This is monumental work, not domestic. This is about the nature of life, love, and the universe, not the details of how women and men live their lives. And Wuthering Heights is exceptional amongst the novels of the period for the absence of any explicit condemnation of Heathcliff’s conduct, or any suggestion that evil might bring its own punishment.

What of today? Will a new generation of teenagers, of readers, be introduced to Cathy and Heathcliff by teachers at school, or librarians, or be inspired to seek the novel out by collections like this? I think so. I think their reactions will be much as my own more than forty years ago, for, despite changes in our lives and expectations – the frantic pace of life, the banishment of boredom, and the lack of solitude – the confusion of first loves and deciding which of our selves we might be (as Cathy does when trying to decide between Heathcliff and Edgar Linton), these emotions are as commonplace now as then. Even if the language and style of the novel might seem to belong to another era, the conflict and story do not.

The history behind the novel and its author is also well known, and has grown a little shabby with retelling. For the most part, over-attention on the biography of a writer is a way of diminishing the power or the uniqueness of her or his imagination. But, in the case of EB (and indeed Charlotte and Anne), there is some justification. Her sense of indifferent or careless Nature comes in part, surely, from the terrible losses they suffered: the early death of their mother and their two older sisters – Maria and Elizabeth – dying as a consequence of neglect and ill treatment at their school. The remaining four children, three girls and a boy, were then tutored at home and, taking refuge in writing and their imaginations, created a secret language and magical universes filled with stars and fantasy. Penning stories and poems on tiny fragments of paper. The freedom and claustrophobia of walking around and around the dining-room table in Haworth at night when the household had gone to bed, the sisters reading passages aloud to one another. The relentless ticking of the clock, the creaking of the wooden floorboards, the wind wuthering in the trees in the graveyard in front of the parsonage. The death of their aunt, and the increasingly dissolute behaviour of their brother Branwell, disappointed and drowning in drink and opiates, and debts. And then, in 1847, three novels published under the pen names of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. Astonishing novels that spoke of the iniquities of the world, of the position of women without income, of violence and passion and of landscape.

Reactions to Wuthering Heights at the time were mixed. Dante Gabriel Rossetti described it as a ‘fiend of a book – an incredible monster’; Atlas as a ‘strange, inartistic story’; and Grantham’s Lady Magazine as ‘a compound of vulgar depravity and unnatural horrors.’ Douglas Jerrold’s Weekly Newspaper said: ‘Wuthering Heights is a strange sort of book – baffling all regular criticism; yet, it is impossible to begin and not finish it; and quite as impossible to lay it aside afterwards and say nothing about it.’ However in the years after Emily Brontë’s death, the novel’s reputation took root: Lord David Cecil considered it the greatest of all Victorian novels, and Matthew Arnold said: ‘For passion, vehemence, and grief she has had no equal since Byron.’

In modern times, critics – such as the great Elaine Showalter, Sandra Gilbert, and Susan Gubar – as well as novelists and poets, from Daphne du Maurier, Helen Oyeyemi, and Margaret Drabble to Sylvia Plath have all admired, considered, been inspired by Brontë’s ‘fiend of a book’. Playwrights and choreographers, artists and composers too, in print, in opera, and song, in ballet, and plays, on screens large and small.

Here, just a few examples: Genesis’s 1976 album Wind and Wuthering and Kate Bush’s chart-topping ‘Wuthering Heights’ released two years later, both of which use direct quotations from the novel itself; the all-female Japanese opera company Takarazuka Revue, and the Northern Ballet Company; Hotbuckle Productions Theatre Company, and The John Godber Company, in a version adapted and directed by Jane Thornton; the leading Asian touring company, Tamasha, with a piece set in the deserts of Rajasthan.

And, of course, film. The earliest known screen adaptation was filmed in England in 1920, though the most famous is the 1939 black-and-white starring Laurence Olivier and Merle Oberon (and David Niven as Edgar). It omitted the second generation’s story, but was firmly situated on the Yorkshire Moors, as was Andrea Arnold’s 2011 adaptation. Luis Buñuel’s 1954 Spanish-language adaptation, Abismos de Pasión, was set in Catholic Mexico, and Yoshishige Yoshida’s 1988 version was set in medieval Japan.

The sheer ingenuity and range of work inspired by Wuthering Heights is testament to the power of the ideas within the novel, the depth of characterisation, and the emotional intention of the story. As technologies change what can be achieved on screen and stage, there will be ever-new interpretations of the text, shaped and refashioned, keeping the passion for the story alive in new generations of audiences all over the world.

Now, here is this collection, published to celebrate the bicentenary of Emily Brontë’s birth in 1818. I won’t spoil the surprise of the stories that follow by summarising the work of the wonderful writers who have contributed, except to say that the pieces are wide-ranging and clever, moving and thought-provoking. Interestingly, a majority are set in modern times, rather than in the period of the novel or indeed EB’s own time. Some are about what we would call – in modern terms – violent and toxic relationships; others about the collision of grief and identity; some are visceral and savage, and others infused with the emotion and beauty of Wuthering Heights. There is even the promise of a school musical! What the stories have in common is that, despite their shared moment of inspiration, they are themselves, and their quality stands testament both to our contemporary writers’ skills, and the timelessness of Wuthering Heights. For, though mores and expectations and opportunities alter, wherever we live and whoever we are, the human heart does not change very much. We understand love and hate, jealousy and peace, grief and injustice, because we experience these things too – as writers, as readers, as our individual selves.

I’ll end where we began, with Emily Brontë’s words – and what is surely one of the most beautiful closing paragraphs in all of literature – as Lockwood looks down on the graves of Heathcliff, Linton, and Cathy. It’s a magnificent full-stop of a sentence.

‘I lingered round them, under the benign sky; watched the moths fluttering among the heath and the harebells, listened to the soft wind breathing through the grass, and wondered how any one could ever imagine unquiet slumbers for the sleepers in that quiet earth.’

TERMINUS

LOUISE DOUGHTY

TWO YOUNG WOMEN ARE standing in a hotel lobby, on either side of a polished-wood reception desk. They are staring at each other.

It is a Tuesday in February. Outside the hotel, lorries bump and thump along a dual carriageway. Beyond the dual carriageway, there is a wide esplanade, and beyond the esplanade a beach, where grey and brown waves chop against the pebbles, and a red warning flag furls and corrugates in the wind before straightening with a snap.

‘Do you have any form of identification?’ the young woman behind the desk asks politely, lightly enough, but the thick ticking of the clock on the wall behind her makes the query sound emphatic.

The hotel lobby is empty, apart from the two women. Victorian-era, once very grand, it has a vaulted ceiling and curving staircase, but the carpet is frayed now, the furniture worn. From the bar and restaurant on the other side of the lobby comes the faint smell of disinfectant and cabbage, even though no one has cooked cabbage in this hotel for over fifty years.

The reception desk is shiny oak; the brass clock ticks loudly; the walls are painted a leaden green colour that hints at a sanatorium. At the end of the reception desk is a white plastic orchid in a brown plastic pot.

Who are you?

Good question.

The other young woman, the one in front of the desk, is called Maria. Maria has never been asked for identification at a hotel before, but then she has never shown up like this, walking in off the street with no luggage, a small backpack, and a stare in her eyes. A beanie hat is pulled low over her black curls, and there are shadows beneath that stare. The receptionist is slender, with a neat navy jacket, and fair hair in an immaculate ponytail. Her skin is very fine, the only make-up she wears is a slick of pale lipstick. Maria knows how she looks to this young woman. They are each other’s inverse.

Maria reaches into the backpack and hands over a driving licence. The receptionist glances at it and hands it back. She doesn’t write anything down. Maria scans the receptionist’s face for signs of suspicion or hostility, but her expression is a calm, professional blank. Maria thinks how habituated she now is to interpretation, how experienced at watching a face.

In high season the room the receptionist offers – a deluxe double with a sea view – would be over two hundred pounds a night, but it’s a Tuesday in February, and Maria gets it for eighty-five. Breakfast is included.

‘Would you like to pay now or at checkout?’ the receptionist asks.

Maria has two credit cards that she has never used: when she applied for the mortgage on her flat three years ago, the broker told her it would be good for her credit rating to have a couple of cards, or even a small loan, as long as she made the repayments on time. The mortgage companies liked evidence of an ability to service debt. This amused Maria at the time, the idea of a company thinking that being in debt already made her a more attractive proposition. She never uses the cards, and, as she pulls one out of her purse, she takes a quick look to check that she has even bothered to sign on the back. She hands it over. That’s how easy it is, she thinks. She can’t use the joint account, but she has the credit cards. The bill won’t arrive for a month.

Why didn’t I think of this before?

The deluxe room is medium-sized and has mushroom-coloured walls. There is a huge sash window, almost floor to ceiling, that looks straight out over a narrow ornamental balcony with rusting ironwork, across the dual carriage-way to the sea. Maria drops her backpack, sits on the bed, and stares at a distant oil rig, blurred against the horizon, the brown-and-grey water still chopping and falling, the red flag furling and snapping repeatedly. After a while, she closes her eyes, begins to breathe deeply, and falls into a short but intense sleep.

When she wakes it is still daylight: just. She rises from the bed, switches the kettle on, makes a cup of tea, and returns to the bed, sitting upright and sipping the tea while she stares at the flag, the oil rig, the rearing waves. She thinks to herself, quite distinctly, So this is what it feels like, a breakdown. She thinks, To get the full benefit, I must not attempt any decisions, not even small ones.

She sips her tea. She watches the flag.

After a while, she needs the loo. The small bathroom also has a huge sash window looking out to sea, with a net curtain. She thinks, I can watch the sea while I pee, and feels a disproportionate amount of pleasure at this unexpected bonus. She thinks, In the short time I have been in this room, I have become obsessed with watching the water. I never want to take my eyes off it.

She lowers her jeans and sits. The bruise on the front of her right upper thigh has spread and altered: it’s now the size of a side plate, the centre of it still purple but fading to red, almost lacy, at the edges. By tomorrow, she knows, it will be tinged with yellow and green. She finishes on the loo, pulls up her jeans with haste, returns to the bed without washing her hands. She sits there, then, staring at the sea until the light fades and the beach darkens and the flag and oil rig become invisible and there are only the sounds in her head: the blur and blare of traffic beneath the window; the crashing of the waves that peaks above the cars and lorries intermittently; the occasional tinkle of something blowing against a nearby balcony – just the sounds, the lift and fall of them in the dark, that’s all there is. She cannot move.

Eventually, with a certain effort of will, she goes back to the bathroom, pees again, and brushes her teeth. She removes her shoes and her socks and her jeans – folding and placing them neatly on the chair in the corner for easy access – and gets into bed, pulling the thick duvet with its slightly shiny cover up over her shoulder, tucking it beneath her chin. Decide nothing, think of nothing. She’s hungry, but she can’t order room service, doesn’t even know if they do room service, as she can’t get up to look at the hotel information folder. Just before she falls asleep, she reaches out to the bedside table and checks that her phone is still turned off, as she has done several times an hour since she left her flat that morning. She falls asleep to the crashing of the waves.

In the morning, she wakes gently. She lies still for a while, eyes closed. The sounds are still there, they colour the room like tea leaves steeping in water, and as they do, she is filled with a sensation she realises she hasn’t felt for a long time: calm. She is lying on her side in a foetal position. Very, very slowly, she unfurls.

She makes an instant coffee, pulls back the curtains, watches the sea in the morning light: it, too, is calmer. The sea is me. Or I am the sea.

Eventually, hunger gets the better of metaphor.

Over breakfast in the deserted dining room, which also overlooks the sea, she does some calculations. In the grey light of day, rested, she feels amazed that she has spent eighty-five pounds on a good night’s sleep. View or no view, she thinks, you could get two pairs of shoes for that. Decent shoes. Paying that much long term is out of the question. She can put it on credit for the time being, but sooner or later that bill will roll in, and she has eight hundred and thirty-three pounds of savings. That won’t do ten nights, let alone the rest of her life.

The rest of her life is too large a thought to grasp. She tries, momentarily. She sips her pleasingly hot coffee, which has come in her own little silver pot, pursing her top lip over the white china cup and taking it in in tiny amounts, inhaling it almost. She tries again: but when she looks beyond the next few days, the weeks and months to come, the enormity of what is to be accomplished, it is as if her imagination shudders and baulks like a nervous horse approaching a high fence.

Six hundred and seventy pounds of her savings came from her Uncle Malcolm – her father’s cousin, who lived alone in a council house in Loughborough and always used to say to her, ‘When I’ve gone, all I’ve got is yours.’ Her father had taken the precaution of warning her not to get excited – Uncle Malcolm was a car park attendant for Tesco, and scarcely had a bean. All the same, when he died of lung cancer at the age of seventy-two, Maria felt guiltily excited to inherit a few hundred quid – poor old Uncle Malcolm. It was the first time she had ever inherited or won anything, the first time anything had come her way that wasn’t earned. She was so excited she had put it in a building society account and done nothing with it because she didn’t want it to be gone. ‘That’s right, duck,’ her father said. ‘Save it for a rainy day.’

Maria and her father both believed in rain. Maria’s mother had died of leukaemia when she was fourteen, and her father had heart disease and hadn’t worked for years. Maria had grown used to the idea that orphanhood was looming, had grown into it, and in due course her father died when she was twenty-two, leaving her just enough for the deposit on a one-bedroom flat in a new development on the edge of the Recreation Ground, where, on Sundays, she was woken by the malice-free shouting and swearing of the local five-a-siders and the occasional bump of a football against the boundary fence.

That was one of Matthew’s observations of her, very early on. On their second date, they walked along the canal towpath after dark, and in a tunnel he stopped and pushed her against the wall. They kissed for a long time in the cold and dank. He pressed on her, his weight, the rough cloth of his jacket with its folds of pockets and buttons and zips, and murmured into her hair, ‘Maria, Maria, you’re an orphan, you’re all alone …’ She cried, then, a little drunk from the wine at dinner, and he held her for a long time, until her feet began to go numb inside her thin suede ankle boots. After a while, he pushed the dark, crinkled locks of hair away from her damp face and looked at her, and she closed her eyes then, knowing he was watching her. He bent his head, to kiss the butterfly-fragile skin of her closed lids, one after the other, then her salty face, and said, ‘You’ll never be alone again, now,’ and something inside her melted and let go.

And even now, sitting sipping coffee in this crumbling wedding cake of a hotel, she can feel that warmth, inside, if she thinks about it, how good it felt, the release of it, to give it all up after all those years of being brave.

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.