Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Come Away with Me"

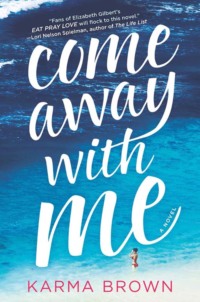

An unexpected journey leads one woman to discover that life after loss is possible, if only you can find the courage to let go…

One minute, Tegan Lawson has everything she could hope for: an adoring husband, Gabe, and a baby on the way. The next, a patch of black ice causes a devastating accident that will change her life in ways she never could have imagined.

Tegan is consumed by grief—not to mention her anger toward Gabe, who was driving on the night of the crash. But just when she thinks she’s hit rock bottom, Gabe reminds her of their Jar of Spontaneity, a collection of their dream destinations and experiences, and so begins an adventure of a lifetime.

From the bustling markets of Thailand to the flavors of Italy to the ocean waves in Hawaii, Tegan and Gabe embark on a journey to escape the tragedy and search for forgiveness. But they soon learn that grief follows you no matter how far away you run, and that acceptance comes when you least expect it. Heartbreaking, hopeful and utterly transporting, Come Away with Me is an unforgettable debut and a luminous celebration of the strength of the human spirit.

Come Away with Me

Karma Brown

Praise for Come Away with Me

“One woman’s journey through grief becomes the journey of a lifetime… This emotional love story will stick with you long after you’ve turned the final page.”

—Colleen Oakley, author of Before I Go

“[A] heartbreaking yet hopeful tale… Karma Brown is a talented new voice in women’s fiction.”

—Lori Nelson Spielman, author of The Life List

“Full of lush locations [and] memorable characters…nothing short of jaw-dropping.”

—Taylor Jenkins Reid, author of Forever, Interrupted and After I Do

“[A] beautifully written story of love and loss…Come Away with Me had me smiling through my tears.”

—Tracey Garvis Graves, New York Times bestselling author of On the Island

KARMA BROWN is an award-winning journalist and freelance writer who probably spends too much time on her laptop in coffee shops. When not writing, she can be found running with her husband, coloring (outside the lines) with her daughter or baking yet another batch of banana muffins. Karma lives just outside Toronto with her family. Come Away with Me is her first novel.

For Adam & Addison, the greatest loves of my life.

And to anyone who has been handed the proverbial lemons of life and made lemonade with them, this book is also for you.

Contents

Cover

Back Cover Text

Title Page

Praise

About the Author

Dedication

Quote

one

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

two

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

three

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

four

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

five

57

58

59

60

six

61

Acknowledgments

Reader’s Guide

Questions for Discussion

A Conversation with Karma Brown

Copyright

Death leaves a heartache no one can heal, love leaves a memory no one can steal.

—From a headstone in Ireland

one

Chicago

1

Even now, the smell of peppermint still makes me cry...

2

We drive the dark streets a little too fast for the weather. Beside me, Gabe crunches a candy cane and drums his thumbs against the steering wheel, singing along to his favorite holiday tune on the radio.

He reaches for the second half of the candy cane with one hand and uses the other to turn up the radio. I tell him to keep his hands on the wheel, but I’m not sure he hears me above the music.

If only he listened, if only I said it louder.

It’s 6:56 p.m. I watch the clock nervously...6:57 p.m. We’re going to be late, and my mother-in-law hates it when we’re late.

At this hour the sky has already turned black, a particularly depressing fact about winter in Chicago. But the twinkling Christmas lights that wind around the lampposts almost make up for it. On vacation from the law firm, with a whole six days of freedom, Gabe is in a feisty and festive mood. Plus, it’s Christmas Eve and we have so many reasons to celebrate this year. He crunches the candy cane enthusiastically, too impatient to savor it. The candy’s sweet, refreshing scent fills the car.

“Your mom is going to lose it,” I say, eyeing the Jetta’s dashboard clock. “We’re going to be so late.”

“Five minutes. Ten tops,” Gabe says. “She’ll live.”

“Wonder if we will.” I give him a wry glance. After eight years of being part of the Lawson family, there are three things I can count on. One, they love to eat, and dropping by for lunch generally means a six-course meal, prepared from scratch by his Italian mother. Two, Gabe inherited his love of life and unwavering positivity from his dad, which I am grateful for. And three, you never, ever, show up late to a Lawson family event...or without a good bottle of red wine.

“You need to relax, my love.” Gabe takes his right hand off the wheel and rests it on my knee briefly, before sliding it up my thigh. His calloused palm—rough from sanding the antique cradle he’s been refinishing, the one I slept in as a baby—scratches against my tights as it works its way along my thigh. The bottle of wine tumbles off my lap.

“Gabe!” I laugh and playfully swat at him. I right the wine bottle and place it between my suede winter boots on the floor. “Get your hand back on the wheel. If this bottle breaks, you’re done for.”

But he keeps his hand where it is. “Trust me,” he murmurs, his smile widening. “This will do the trick.”

“We’re almost there,” I protest, pressing my hand down hard on his, temporarily stopping its climb. “Let’s save this for later, okay? When we’re not late and you’re not driving.”

“Don’t worry, I’m an expert one-handed driver,” he says, inching his hand higher despite my efforts. “Besides, I don’t want you going into my parents’ house all wound up. You know how my mom smells fear.” He turns and winks at me, and I melt. Like always.

His fingers hook the thick waistband of my tights, which sit just underneath my newly swelling belly, and I stop protesting.

Rockin’ around the Christmas tree...have a happy holiday...

My breath catches as Gabe’s fingers work their way past the waistband and into my not sexy, but quite practical, maternity underwear. I look over at him but he stares straight ahead, a smile playing on his lips. I close my eyes and lean my head against the headrest, as Gabe’s hand moves lower...

Then, suddenly, too much movement in all the wrong directions. Like riding a roller coaster with closed eyes, unable to figure out which turn is coming next. Except there’s no exhilaration—only panic at the realization Gabe no longer has control over the car. The tires lose their grip on the road and Gabe’s fingers wrench from between my legs. I gasp out his name and brace my hands against the edges of my seat. We fishtail side to side, and for a moment it seems as though Gabe is back in control. I allow myself a split second of relief. One quick thought that being late to dinner isn’t the worst thing that could happen, after all. An instant to contemplate how lucky we are.

Then, with a sickening lurch, the car swerves. The momentum is so great it tosses me sideways like a rag doll, and my head cracks against the window. Stars explode behind my eyes, mingling with the lampposts’ twinkle lights and creating a dizzying kaleidoscope. I feel like I’m watching a lit Ferris wheel, spinning high in the night sky.

As our car smashes into the lamppost, steel meets steel and everything slows down. I wonder if the bottle of wine will be okay. I think that at least now we have a good excuse for being late for dinner. And I’m amazed the radio continues playing, as if nothing has changed.

After the impact comes the shriek of metal as our sturdy car rips practically in two. And still, the music plays. When the airbag explodes into my face and chest I worry I may suffocate. But then a rush of pain, deep and frightening, crushes my belly—where the most important thing to both of us is nestled—and it takes my breath away.

Seconds later, everything goes quiet.

I try to call out for Gabe, but have no air left to make a sound. With my left hand I reach out, hoping to feel him beside me. I need to tell him something is wrong. My head hurts terribly.

He’ll know what to do.

But there’s nothing beside me except cold, empty space.

Then I realize it’s snowing inside the car.

We will not be lucky this time.

3

The biscotto shatters into a million pieces, the butter knife clanging against the fine china plate I’d planned to use for Christmas dinner. Back when I was looking forward to Christmas. Or to anything. Staring into the crumbs, I realize how closely they resemble my life. No one piece big enough to be satisfying; too many that even if you try to gather them all, a few will be left behind. Lost forever in the cracks.

“I don’t know why you insist on trying to cut that stuff.” Gabe leans against the doorjamb between our kitchen and the hallway.

“Because I only want half,” I say. “Why do they have to make them so damn long?”

“So you don’t burn your fingers when you dip them in your coffee,” he replies, shrugging. Obviously, his expression adds, though he doesn’t say anything out loud.

I sigh, tucking a stringy piece of dark hair behind my ear. “Why are you still here anyway?” It’s two o’clock in the afternoon on a Wednesday, the middle of a workday. It’s been a long time since I went to work, nearly three months. I pick up a small chunk of the broken biscotto and dip it in my coffee, appreciating the hot liquid’s burn against my skin. Physical pain is good. It dulls the ache that won’t leave my chest.

Gabe moves into the kitchen and sits on the empty stool beside me at the island. “I live here,” he says, his tone purposefully light. He’s trying to bring a smile to my face, I know, like he used to so easily.

The soggy corner of the cookie falls from my fingers and disappears below the surface of the coffee. “Besides, you need me,” he adds with a resigned sigh. “I’m not going anywhere.”

I look back into my mug, oily dots popping to the surface, and grab another piece of biscotto. My mother-in-law, Rosa, brought it over earlier, a whole tray’s worth, because she believes eating dilutes grief. But the cookies are Gabe’s favorite, not mine. To be honest, I don’t much care for them although I didn’t have the heart to tell his mom. Especially not now.

I put the thick, crusty cookie on the plate and pick up the knife again. Gabe raises an eyebrow but I ignore him, cutting the piece in half, once again unsuccessfully.

My mother bustles into the kitchen and I glance up at the stack of tiny folded blankets, covered in green turtles and fuzzy brown teddy bears, she holds in her arms. “What would you like me to do with these?” She looks uncomfortable to be asking the question, even though I’ve asked her here specifically to help pack up the nursery—something Gabe and I are incapable of facing alone.

“Get rid of them, please,” I say as if I’m talking about tomato soup cans in our trash bin. “Give them away or something.”

My mom opens her mouth, then closes it as she fingers the fine, muslin blanket on top of the pile—the one I imagined swaddling our son in before rocking him to sleep. “I could just put them in storage, until you’re sure.”

“No,” I say, shaking my head. The air in the kitchen is charged with tension. No one knows how to deal with me these days; I can’t say I blame them. If I could escape my body and mind, I wouldn’t look back. “Give them away. Or throw them out. I don’t really care, as long as they’re gone.”

“Are you sure?” Gabe asks. He looks sad. But I’m sure I look worse. I tuck my hair behind my ear again, smelling how long it’s been since my last shower.

My mom hasn’t moved. She’s standing on the other side of the island and staring down at the blankets, sweeping her hands across the top one to try and straighten out the wrinkles. It occurs to me she imagined wrapping her grandson in that blanket, too.

“Get rid of them,” I say with an edge this time. But I keep my eyes on Gabe, who has gotten up and is now standing beside my mom. I’m challenging him to argue. “Please don’t make me say it again.”

“Okay, hon, okay,” Mom says, looking apologetic before leaving us to finish the conversation I don’t want to have.

“I’m sorry, Tegan.” Gabe’s voice carries a sadness I understand but don’t want to deal with.

I pick up another biscotto and put it on the plate full of broken cookie pieces. “I know,” I reply, setting the knife directly in the middle of the cookie. I press down firmly and a large chunk of the biscotto flies off the plate, still intact. Finally. “But it doesn’t really matter anymore, does it?”

4

“I’ve never seen you look more beautiful.” Gabe is beside me on our couch. I’m looking at the collection of photos on my lap that have yet to make it to a scrapbook or album. I shuffle through the photos, stopping at one of Gabe and me in Millennium Park, in front of Cloud Gate, or what Chicagoans call “the Bean.” In it Gabe kisses my cheek, my one foot kicked up and my hands holding the dress’s frothy layers of material in a sashay move. Our image is reflected back in the Bean’s smooth, shiny steel surface, along with the Chicago skyline and a slew of strangers, now part of our memories. A day I’ll never forget.

“Aside from the tinge of green on my face,” I say. Remembering. It’s only been six months, but feels like a lifetime.

We were married at dusk, during an early September heat wave. The ceremony was on the rooftop of the Wit hotel under the glass roof, which, along with the potted magnolia bushes that were somehow in bloom despite the season, made it feel as though we were inside a terrarium. Glowing lanterns lined the aisle and guests sat on low, white couches that would later become seating for the reception. It was all much more than we could afford, me a kindergarten teacher and Gabe just out of law school. But his well-off parents insisted—and paid—so the Wit it was.

I was horribly sick at the wedding, throwing up most of the day—including right after the picture at the Bean, in a bag Gabe wisely tucked in his suit pocket, “just in case”—and only five minutes before I walked down the lantern-lit aisle. Luckily my best friend and maid of honor, Anna, grabbed a wine bucket just in time. My mother-in-law blamed the catering from the rehearsal dinner the night before, which my parents had organized. My mom, bristling at Gabe’s mother’s implication, suggested it was nerves, telling all who would listen I’d always had a weak stomach when I was nervous. As a child that was quite true. I did my fair share of vomiting before important school exams, anytime I had to public speak and, most unfortunately, onstage when I was one of the three little pigs in the school play. But I had outgrown my “nervous stomach,” and figured I’d just caught a bug from school. When you teach five-and six-year-olds all day you spend a good part of the year ill.

Gabe was so sweet that morning. Sending me a prewedding gift of a dozen yellow roses, a bottle of pink bismuth for my stomach and a card that read:

You’ve always looked good in green—ha-ha. You are my forever.

G xo

Even sick, it was the best day of my life.

We found out a week later it had nothing to do with food poisoning, or nerves, or a virus. I was pregnant. I’d never seen Gabe happier than when he opened the envelope I gave him, telling him it was a leftover wedding card previously misplaced. When he pulled out the card, which had a baby rattle and “Congratulations” printed on its front, at first he looked confused. Then I handed him the pregnancy test stick, with a bright pink plus sign, and he burst into tears. He grabbed me and spun me around, laughing and hollering with joy, until I couldn’t see straight. There is nothing like being able to give your husband, the man you’ve loved since the day you laid eyes on him, a dream come true.

We met at Northwestern in our first year, during frosh week. My dorm was having an unsanctioned floor crawl. Gabe, who had been invited by a friend who lived in my dorm, had backed into me coming out of the Purple Jesus room, his giant Slurpee-sized cup of grape Kool-Aid mixed with high-proof vodka spilling all over both of us. Shocked at the cold, rubbing-alcohol-scented drink sopping into my white T-shirt and shorts, I simply stared at him, my mouth open. But then we burst out laughing, and he offered to help clean me up in the women’s washroom, which also happened to be the orgasm shooter room for the night.

“How apropos,” Gabe said, wiggling his eyebrows at me and handing me a shot glass. I laughed again, tossing back the sickly sweet shooter.

“Thanks,” I said. “That was the best one I’ve ever had.”

While we’d been together for so many years after that, our lives intertwined, the day we were married was the day it all really began. If only we’d had more time to bask in that happiness. There was a carton of orange juice in our fridge that had lasted nearly as long.

I stack the photos back together, not bothering to wipe away my tears.

“Teg, please don’t cry.” Gabe shifts closer to me, but I can barely feel his touch. I’m so numb.

“Do you think I’ll ever be happy again?” I close the lid on the box of photos. Saving them for the same time tomorrow night. “I mean, really happy?”

“I know it,” he says. “You’re just not ready yet, love.”

I touch my necklace, still trying to get used to it. It’s a white-gold, round pendant, about the size of a quarter and a half-inch thick. It hangs from a delicate chain. And while the pendant was hollow when the necklace arrived, via a white-and-orange FedEx box nowhere near special enough for its cargo, it’s now filled with the ashes of a broken dream.

I chose the necklace off the internet shortly after I was released from the hospital, one late night when sleep was impossible. I considered an urn, but somehow it felt wrong. That’s how my grandma had kept Gramps’s ashes, in an ornate brass urn on her kitchen windowsill. “Where we can still kiss him every day, the sun and me,” she liked to say.

In truth, twenty-six felt too young to keep—or need, for that matter—an urn of any kind. I casually mentioned the idea of something a little more intimate to Anna, hoping she’d tell me wearing a necklace filled with ashes wasn’t at all weird, but her frown and pinched look suggested otherwise. Gabe hadn’t been much help, either. None of us wanted to deal with the horror, but I didn’t have that luxury because it was my body that was now hollow. Empty, like my gold necklace used to be.

Gabe glances at the pendant. “You don’t have to wear it all the time, you know.”

“Yes, I do.”

“Does it...make you feel better?” he asks, shifting sideways so he can face me straight on.

I pause for a moment. “No.” Then I turn my head and look at him before quickly turning away. I don’t like his look. It’s a complex mix of concern, sorrow and frustration.

“I’m worried it’s making things worse, Tegan.”

Anger burns in my belly. The last thing I should have to do is explain myself. Especially after what he’s done to us, to me. “How could anything make this worse?” My voice is low, unsteady.

“You know what I mean,” he says.

“Obviously I don’t.” I slam the box of photos on the coffee table and stand up so quickly I feel woozy.

“Hey, hey, Tegan,” he soothes, and I know if I were still on the couch he’d reach for me. But I’m just out of his grasp, and neither of us tries to close the distance. “I want to understand. I’m just trying to help.”

How do you explain that if you could, you’d cut your chest open and pour the ashes right inside so they could forever lie next to your heart? Like a blanket to smother the chill of sorrow. You can’t, so you don’t.

Gabe and I are the only ones who know exactly what’s in the necklace. Well, us and the funeral director, who filled it at my request. Close to my heart. It’s the only way I can keep breathing.

“I’m going to bed,” I say. My muscles ache as I walk slowly to the bedroom, making the space between us even greater. I’m so fragile these days, paper-thin. Even though I’m only halfway through my twenties, I feel more like a ninety-year-old. Probably because for the past couple of months I’ve done little aside from move in a daze from couch, to bed and back.

I barely remember what it feels like to get up and get ready for work. To enjoy takeout during one of the nature shows Gabe loves to watch, to shop for shoes or bags or the very short dresses Anna likes to fill her closet with, hopeful for date nights. I forget what it’s like to have a purpose that gets me up each morning.

These days I care little about what’s happening beyond my four apartment walls. I don’t remember what fresh air smells like, except for when Mom opens one of the apartment windows, touting fresh air as effective an elixir as anything else. The late winter chill that tickles my senses always feels good, but I don’t want to feel good. Not yet. It has only been seventy-nine days. So I ask her to shut the window and she sighs, but she always does it. That’s the thing about going through something like this. People will do anything to try and make you happy again; they’ll give you whatever you want. Except that the thing you really want you can never have again, and no one can bring it back.

“I’ll come with you,” Gabe says, from behind me.

“You don’t have to,” I reply, although I don’t mean it. As much as I am still so angry with Gabe, still full of rage and blame, I don’t like to sleep alone.

“I want to.”

“Fine,” I say, pushing the door to our bedroom open. As I do, I glance into the guest room to my right. The door is supposed to be closed—I’ve been quite clear about that—but it’s wide-open. Beckoning me.

The pile of baby blankets rests on the dresser, which would have doubled as a change table to save precious space in our not-so-spacious apartment. My mom must have forgotten to close the door when she left. Casting my eyes around the dim room, the bile rises in the back of my throat. Pushed up against one wall, the crib is still covered by a white sheet, with the mobile—plush baseballs and baseball bats, which Gabe had picked out as soon as we found out it was a boy—creating a peak in the sheet’s middle like a circus tent. In another corner I see the cradle, which Gabe had restored beautifully, waiting for a final coat of stain. Even though we still had months to go, we had been ready for our boy’s arrival.

Feeling sick, I turn away and shut the door firmly. Perhaps tomorrow I’ll agree to the crib being taken apart. It will have been eighty days, nearly three months, and I know I’ll soon have to accept no baby will ever sleep here, gazing with wide, curious eyes as the mobile circles soothingly overhead.

As I settle into our bed, pulling the sheets—which smell clean and fresh, thanks to Gabe, or my mom, or someone else who takes care of the things I no longer seem able to—up to my chin, I try to pretend none of it happened.

But the nightmares won’t let me forget, not even while I sleep.