Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "The Monsters and the Critics"

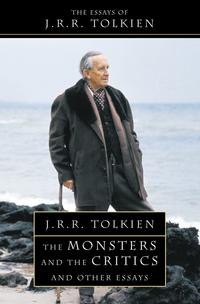

THE MONSTERS AND THE CRITICS

and Other Essays

J.R.R. Tolkien

Edited by Christopher Tolkien

CONTENTS

Title Page

Foreword

Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics

On Translating Beowulf

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

On Fairy-Stories

English and Welsh

A Secret Vice

Valedictory Address to the University Of Oxford

Footnotes

Also by J.R.R. Tolkien

Copyright

About the Publisher

FOREWORD

With one exception, all the ‘essays’ by J. R. R. Tolkien collected together in this book were in fact lectures, delivered on special occasions; and while all were on specific topics, literary or linguistic, the whole audience on those occasions could in no case (save perhaps that of the Valedictory Address) be presumed to have more than a general knowledge of or interest in the subjectfn1 – and the one piece in this collection that was not a lecture, On Translating Beowulf, was not addressed to experts in the study of the poem. It is this common quality that is the basis of this book (other published writings of my father’s deriving from his studies in early English were articles, not lectures, and were written with a specialized readership in mind); but indeed I think it will be found that all seven papers, though covering a period of nearly thirty years, and on quite different subjects, nonetheless constitute a unity.

In addition to the five pieces that have been previously published I have ventured to include two that have not, though both were publicly delivered. One of these, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, was my father’s principal pronouncement on the poem to which he devoted so much thought and study. The other, A Secret Vice, is unique, in that only on this one occasion, as it seems, did the ‘invented world’ appear publicly and in its own right in the ‘academic world’ – and that was some six years before the publication of The Hobbit and nearly a quarter of a century before that of The Lord of the Rings. It is of great interest in the history of the invented languages, and this seems a good opportunity and a suitable context for its publication: for it touches on themes developed in later essays in this book.

The first piece in this collection, Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics, was the Sir Israel Gollancz Memorial Lecture to the British Academy, read on 25 November 1936, and was published in volume XXII of the Proceedings of the Academy (from which copies of the lecture are available). I acknowledge with thanks the permission of the British Academy, owners of the copyright, to reprint it here; and also permission to use the title of the lecture in the title of this book.

On Translating Beowulf was contributed, as ‘Prefatory Remarks on Prose Translation of “Beowulf”’, to a new edition (1940) by Professor C. L. Wrenn of Beowulf and the Finnesburg Fragment, A Translation into Modern English Prose, by John R. Clark Hall (1911).

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight was the W. P. Ker Memorial Lecture in the University of Glasgow, delivered on 15 April 1953. Of this there seems to exist now only one text, a typescript made after the delivery of the lecture (which possibly suggests an intention to publish it), as appears from the statement (See here) ‘Here the temptation-scenes were read aloud in translation.’ My father’s translation of Sir Gawain into alliterative verse in modern English had then been very recently completed. This translation was broadcast in dramatized form by the BBC in December 1953 (repeated in the following year), and the introduction to the poem which I included in the volume of translations (Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo, 1975) was taken from the radio talk which followed the broadcasts: this, though very brief, is closely related to the lecture printed here.

There are some minor matters concerning its presentation which must be mentioned. Despite my father’s statement (See here) that ‘where quotation is essential I will use a translation which I have just completed’, he did not in fact do so throughout, several substantial quotations being given in the original. There does not seem to be any significance in this, however, and I have therefore substituted the translation in such cases. Moreover the translation at that time differed in many details of wording from the revised form published in 1975; and in all such differences I have substituted the latter. I have not inserted the ‘temptation scenes’ at the point where my father recited them when delivering the lecture, because if these are given in full they run to some 350 lines, and there is no indication in the text of how he reduced them. And lastly, since some readers may wish to refer to the translation rather than to the original poem (edited by J. R. R. Tolkien and E. V. Gordon, second edition revised by N. Davis, Oxford 1967), but the former gives only stanza-numbers and the latter only line-numbers, I have given both: thus 40.970 means that line 970 is found in the 40th stanza.

The fourth essay, On Fairy-Stories, was originally an Andrew Lang lecture given at the University of St Andrews on 8 March 1939.fn2 It was first published in the memorial volume Essays Presented to Charles Williams (Oxford 1947), and reissued (first in 1964) together with the story Leaf by Niggle under the title Tree and Leaf. For this some minor alterations were made, and it is this later text that is given here (with the correction of some errors that go back to the 1964 reprinting).

English and Welsh was an O’Donnell Lecture given at Oxford on 21 October 1955 (the day after the publication of The Return of the King, as noted by Humphrey Carpenter in his Biography, p. 223). These lectures were established in the Universities of Oxford, Edinburgh, and Wales to treat of ‘the British or Celtic element in the English language and the dialects of English Counties and the special terms and words used in agriculture or handicrafts and the British or Celtic element in the existing population of England’; and English and Welsh was the opening lecture of a series given at Oxford. It was published in a collection entitled Angles and Britons: O’Donnell Lectures (University of Wales Press 1963); the copyright is owned by the University of Oxford, whose permission to publish it in this book I acknowledge with thanks.

A Secret Vice exists in a single manuscript without date or indication of the occasion of its delivery; but that the audience was a philological society is evident, and the Esperanto Congress in Oxford, referred to at the beginning of the essay as having taken place ‘a year or more ago’, was held in July 1930. Thus the date can be fixed as 1931. The manuscript was later hurriedly revised here and there, apparently for a second delivery of the paper long after – the words ‘more than 20 years’ (See here) were changed to ‘almost 40 years’; and I have adopted some of these revisions in the text printed. The ironic title in the manuscript itself is A Hobby for the Home (with a later note: ‘In other words: home-made or invented languages’), but my father referred to it in 1967 by a different title: ‘The amusement of making up languages is very common among children (I once wrote a paper on it, called A Secret Vice)’ (The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, p. 374). The words ‘a secret vice’ occur in the essay; and I have adopted this title. At the end I have given a much later version of one of the ‘Elvish’ poems included in the text, since it is one of the major pieces of Quenya (and incidentally upholds the now well-established tradition that all my father’s writings have appendices).

The last piece in the book is the Valedictory Address delivered in Oxford on 5 June 1959, at the end of my father’s last term as Merton Professor of English Language and Literature. This has been previously published in J. R. R. Tolkien, Scholar and Storyteller, edited by Mary Salu and Robert T. Farrell, Cornell University Press 1979; but there are many copies of this lecture, and since I made available the text for that volume I have come upon another to which my father made a good many alterations (without in any way changing the argument); these changes are incorporated in the text printed here. Whether they were made before or after the Valedictory Address was delivered I cannot say.

Only in the case of the previously unpublished pieces is this book in any sense an ‘edition’; to those previously published I have added no annotation of any kind, save for a few explanations of detail in the Valedictory Address. The unpublished pieces, being derived from the author’s own texts which are not in altogether final form, are on a different footing, but here also my notes are kept to a minimum and largely restricted to references and textual details.

I wish to thank Rayner Unwin for much help and advice in the planning of the book.

CHRISTOPHER TOLKIEN

BEOWULF: THE MONSTERS AND THE CRITICS

In 1864 the Reverend Oswald Cockayne wrote of the Reverend Doctor Joseph Bosworth, Rawlinsonian Professor of Anglo-Saxon: ‘I have tried to lend to others the conviction I have long entertained that Dr Bosworth is not a man so diligent in his special walk as duly to read the books … which have been printed in our old English, or so-called Anglosaxon tongue. He may do very well for a professor.’1 These words were inspired by dissatisfaction with Bosworth’s dictionary, and were doubtless unfair. If Bosworth were still alive, a modern Cockayne would probably accuse him of not reading the ‘literature’ of his subject, the books written about the books in the so-called Anglo-Saxon tongue. The original books are nearly buried.

Of none is this so true as of The Beowulf, as it used to be called. I have, of course, read The Beowulf, as have most (but not all) of those who have criticized it. But I fear that, unworthy successor and beneficiary of Joseph Bosworth, I have not been a man so diligent in my special walk as duly to read all that has been printed on, or touching on, this poem. But I have read enough, I think, to venture the opinion that Beowulfiana is, while rich in many departments, specially poor in one. It is poor in criticism, criticism that is directed to the understanding of a poem as a poem. It has been said of Beowulf itself that its weakness lies in placing the unimportant things at the centre and the important on the outer edges. This is one of the opinions that I wish specially to consider. I think it profoundly untrue of the poem, but strikingly true of the literature about it. Beowulf has been used as a quarry of fact and fancy far more assiduously than it has been studied as a work of art.

It is of Beowulf, then, as a poem that I wish to speak; and though it may seem presumption that I should try with swich a lewed mannes wit to pace the wisdom of an heep of lerned men, in this department there is at least more chance for the lewed man. But there is so much that might still be said even under these limitations that I shall confine myself mainly to the monsters – Grendel and the Dragon, as they appear in what seems to me the best and most authoritative general criticism in English – and to certain considerations of the structure and conduct of the poem that arise from this theme.

There is an historical explanation of the state of Beowulfiana that I have referred to. And that explanation is important, if one would venture to criticize the critics. A sketch of the history of the subject is required. But I will here only attempt, for brevity’s sake, to present my view of it allegorically. As it set out upon its adventures among the modern scholars, Beowulf was christened by Wanley Poesis – Poeseos Anglo-Saxonicæ egregium exemplum. But the fairy godmother later invited to superintend its fortunes was Historia. And she brought with her Philologia, Mythologia, Archaeologia, and Laographia.2 Excellent ladies. But where was the child’s name-sake? Poesis was usually forgotten; occasionally admitted by a side-door; sometimes dismissed upon the door-step. ‘The Beowulf’, they said, ‘is hardly an affair of yours, and not in any case a protégé that you could be proud of. It is an historical document. Only as such does it interest the superior culture of today.’ And it is as an historical document that it has mainly been examined and dissected. Though ideas as to the nature and quality of the history and information embedded in it have changed much since Thorkelin called it De Danorum Rebus Gestis, this has remained steadily true. In still recent pronouncements this view is explicit. In 1925 Professor Archibald Strong translated Beowulf into verse;3 but in 1921 he had declared: ‘Beowulf is the picture of a whole civilization, of the Germania which Tacitus describes. The main interest which the poem has for us is thus not a purely literary interest. Beowulf is an important historical document.’4

I make this preliminary point, because it seems to me that the air has been clouded not only for Strong, but for other more authoritative critics, by the dust of the quarrying researchers. It may well be asked: why should we approach this, or indeed any other poem, mainly as an historical document? Such an attitude is defensible: firstly, if one is not concerned with poetry at all, but seeking information wherever it may be found; secondly, if the so-called poem contains in fact no poetry. I am not concerned with the first case. The historian’s search is, of course, perfectly legitimate, even if it does not assist criticism in general at all (for that is not its object), so long as it is not mistaken for criticism. To Professor Birger Nerman as an historian of Swedish origins Beowulf is doubtless an important document, but he is not writing a history of English poetry. Of the second case it may be said that to rate a poem, a thing at the least in metrical form, as mainly of historical interest should in a literary survey be equivalent to saying that it has no literary merits, and little more need in such a survey then be said about it. But such a judgement on Beowulf is false. So far from being a poem so poor that only its accidental historical interest can still recommend it, Beowulf is in fact so interesting as poetry, in places poetry so powerful, that this quite overshadows the historical content, and is largely independent even of the most important facts (such as the date and identity of Hygelac) that research has discovered. It is indeed a curious fact that it is one of the peculiar poetic virtues of Beowulf that has contributed to its own critical misfortunes. The illusion of historical truth and perspective, that has made Beowulf seem such an attractive quarry, is largely a product of art. The author has used an instinctive historical sense – a part indeed of the ancient English temper (and not unconnected with its reputed melancholy), of which Beowulf is a supreme expression; but he has used it with a poetical and not an historical object. The lovers of poetry can safely study the art, but the seekers after history must beware lest the glamour of Poesis overcome them.

Nearly all the censure, and most of the praise, that has been bestowed on The Beowulf has been due either to the belief that it was something that it was not – for example, primitive, pagan, Teutonic, an allegory (political or mythical), or most often, an epic; or to disappointment at the discovery that it was itself and not something that the scholar would have liked better – for example, a heathen heroic lay, a history of Sweden, a manual of Germanic antiquities, or a Nordic Summa Theologica.

I would express the whole industry in yet another allegory. A man inherited a field in which was an accumulation of old stone, part of an older hall. Of the old stone some had already been used in building the house in which he actually lived, not far from the old house of his fathers. Of the rest he took some and built a tower. But his friends coming perceived at once (without troubling to climb the steps) that these stones had formerly belonged to a more ancient building. So they pushed the tower over, with no little labour, in order to look for hidden carvings and inscriptions, or to discover whence the man’s distant forefathers had obtained their building material. Some suspecting a deposit of coal under the soil began to dig for it, and forgot even the stones. They all said: ‘This tower is most interesting.’ But they also said (after pushing it over): ‘What a muddle it is in!’ And even the man’s own descendants, who might have been expected to consider what he had been about, were heard to murmur: ‘He is such an odd fellow! Imagine his using these old stones just to build a nonsensical tower! Why did not he restore the old house? He had no sense of proportion.’ But from the top of that tower the man had been able to look out upon the sea.

I hope I shall show that that allegory is just – even when we consider the more recent and more perceptive critics (whose concern is in intention with literature). To reach these we must pass in rapid flight over the heads of many decades of critics. As we do so a conflicting babel mounts up to us, which I can report as something after this fashion.5 ‘Beowulf is a half-baked native epic the development of which was killed by Latin learning; it was inspired by emulation of Virgil, and is a product of the education that came in with Christianity; it is feeble and incompetent as a narrative; the rules of narrative are cleverly observed in the manner of the learned epic; it is the confused product of a committee of muddleheaded and probably beer-bemused Anglo-Saxons (this is a Gallic voice); it is a string of pagan lays edited by monks; it is the work of a learned but inaccurate Christian antiquarian; it is a work of genius, rare and surprising in the period, though the genius seems to have been shown principally in doing something much better left undone (this is a very recent voice); it is a wild folk-tale (general chorus); it is a poem of an aristocratic and courtly tradition (same voices); it is a hotch-potch; it is a sociological, anthropological, archaeological document; it is a mythical allegory (very old voices these and generally shouted down, but not so far out as some of the newer cries); it is rude and rough; it is a masterpiece of metrical art; it has no shape at all; it is singularly weak in construction; it is a clever allegory of contemporary politics (old John Earle with some slight support from Mr Girvan, only they look to different periods); its architecture is solid; it is thin and cheap (a solemn voice); it is undeniably weighty (the same voice); it is a national epic; it is a translation from the Danish; it was imported by Frisian traders; it is a burden to English syllabuses; and (final universal chorus of all voices) it is worth studying.’

It is not surprising that it should now be felt that a view, a decision, a conviction are imperatively needed. But it is plainly only in the consideration of Beowulf as a poem, with an inherent poetic significance, that any view or conviction can be reached or steadily held. For it is of their nature that the jabberwocks of historical and antiquarian research burble in the tulgy wood of conjecture, flitting from one tum-tum tree to another. Noble animals, whose burbling is on occasion good to hear; but though their eyes of flame may sometimes prove searchlights, their range is short.

None the less, paths of a sort have been opened in the wood. Slowly with the rolling years the obvious (so often the last revelation of analytic study) has been discovered: that we have to deal with a poem by an Englishman using afresh ancient and largely traditional material. At last then, after inquiring so long whence this material came, and what its original or aboriginal nature was (questions that cannot ever be decisively answered), we might also now again inquire what the poet did with it. If we ask that question, then there is still, perhaps, something lacking even in the major critics, the learned and revered masters from whom we humbly derive.

The chief points with which I feel dissatisfied I will now approach by way of W. P. Ker, whose name and memory I honour. He would deserve reverence, of course, even if he still lived and had not ellor gehworfen on Frean wœre upon a high mountain in the heart of that Europe which he loved: a great scholar, as illuminating himself as a critic, as he was often biting as a critic of the critics. None the less I cannot help feeling that in approaching Beowulf he was hampered by the almost inevitable weakness of his greatness: stories and plots must sometimes have seemed triter to him, the much-read, than they did to the old poets and their audiences. The dwarf on the spot sometimes sees things missed by the travelling giant ranging many countries. In considering a period when literature was narrower in range and men possessed a less diversified stock of ideas and themes, one must seek to recapture and esteem the deep pondering and profound feeling that they gave to such as they possessed.

In any case Ker has been potent. For his criticism is masterly, expressed always in words both pungent and weighty, and not least so when it is (as I occasionally venture to think) itself open to criticism. His words and judgements are often quoted, or reappear in various modifications, digested, their source probably sometimes forgotten. It is impossible to avoid quotation of the well-known passage in his Dark Ages:

A reasonable view of the merit of Beowulf is not impossible, though rash enthusiasm may have made too much of it, while a correct and sober taste may have too contemptuously refused to attend to Grendel or the Fire-drake. The fault of Beowulf is that there is nothing much in the story. The hero is occupied in killing monsters, like Hercules or Theseus. But there are other things in the lives of Hercules and Theseus besides the killing of the Hydra or of Procrustes. Beowulf has nothing else to do, when he has killed Grendel and Grendel’s mother in Denmark: he goes home to his own Gautland, until at last the rolling years bring the Fire-drake and his last adventure. It is too simple. Yet the three chief episodes are well wrought and well diversified; they are not repetitions, exactly; there is a change of temper between the wrestling with Grendel in the night at Heorot and the descent under water to encounter Grendel’s mother; while the sentiment of the Dragon is different again. But the great beauty, the real value, of Beowulf is in its dignity of style. In construction it is curiously weak, in a sense preposterous; for while the main story is simplicity itself, the merest commonplace of heroic legend, all about it, in the historic allusions, there are revelations of a whole world of tragedy, plots different in import from that of Beowulf, more like the tragic themes of Iceland. Yet with this radical defect, a disproportion that puts the irrelevances in the centre and the serious things on the outer edges, the poem of Beowulf is undeniably weighty. The thing itself is cheap; the moral and the spirit of it can only be matched among the noblest authors.6

This passage was written more than thirty years ago, but has hardly been surpassed. It remains, in this country at any rate, a potent influence. Yet its primary effect is to state a paradox which one feels has always strained the belief, even of those who accepted it, and has given to Beowulf the character of an ‘enigmatic poem’. The chief virtue of the passage (not the one for which it is usually esteemed) is that it does accord some attention to the monsters, despite correct and sober taste. But the contrast made between the radical defect of theme and structure, and at the same time the dignity, loftiness in converse, and well-wrought finish, has become a commonplace even of the best criticism, a paradox the strangeness of which has almost been forgotten in the process of swallowing it upon authority.7 We may compare Professor Chambers in his Widsith, p. 79, where he is studying the story of Ingeld, son of Froda, and his feud with the great Scylding house of Denmark, a story introduced in Beowulf merely as an allusion.

Nothing [Chambers says] could better show the disproportion of Beowulf which ‘puts the irrelevances in the centre and the serious things on the outer edges’, than this passing allusion to the story of Ingeld. For in this conflict between plighted troth and the duty of revenge we have a situation which the old heroic poets loved, and would not have sold for a wilderness of dragons.

I pass over the fact that the allusion has a dramatic purpose in Beowulf that is a sufficient defence both of its presence and of its manner. The author of Beowulf cannot be held responsible for the fact that we now have only his poem and not others dealing primarily with Ingeld. He was not selling one thing for another, but giving something new. But let us return to the dragon. ‘A wilderness of dragons.’ There is a sting in this Shylockian plural, the sharper for coming from a critic, who deserves the title of the poet’s best friend. It is in the tradition of the Book of St Albans, from which the poet might retort upon his critics: ‘Yea, a desserte of lapwyngs, a shrewednes of apes, a raffull of knaues, and a gagle of gees.’

As for the poem, one dragon, however hot, does not make a summer, or a host; and a man might well exchange for one good dragon what he would not sell for a wilderness. And dragons, real dragons, essential both to the machinery and the ideas of a poem or tale, are actually rare. In northern literature there are only two that are significant. If we omit from consideration the vast and vague Encircler of the World, Miðgarðsormr, the doom of the great gods and no matter for heroes, we have but the dragon of the Völsungs, Fáfnir, and Beowulf’s bane. It is true that both of these are in Beowulf, one in the main story, and the other spoken of by a minstrel praising Beowulf himself. But this is not a wilderness of dragons. Indeed the allusion to the more renowned worm killed by the Wælsing is sufficient indication that the poet selected a dragon of well-founded purpose (or saw its significance in the plot as it had reached him), even as he was careful to compare his hero, Beowulf son of Ecgtheow, to the prince of the heroes of the North, the dragon-slaying Wælsing. He esteemed dragons, as rare as they are dire, as some do still. He liked them – as a poet, not as a sober zoologist; and he had good reason.

But we meet this kind of criticism again. In Chambers’s Beowulf and the Heroic Age – the most significant single essay on the poem that I know – it is still present. The riddle is still unsolved. The folk-tale motive stands still like the spectre of old research, dead but unquiet in its grave. We are told again that the main story of Beowulf is a wild folk-tale. Quite true, of course. It is true of the main story of King Lear, unless in that case you would prefer to substitute silly for wild. But more: we are told that the same sort of stuff is found in Homer, yet there it is kept in its proper place. ‘The folk-tale is a good servant’, Chambers says, and does not perhaps realize the importance of the admission, made to save the face of Homer and Virgil; for he continues: ‘but a bad master: it has been allowed in Beowulf to usurp the place of honour, and to drive into episodes and digressions the things which should be the main stuff of a well-conducted epic.’8 It is not clear to me why good conduct must depend on the main stuff. But I will for the moment remark only that, if it is so, Beowulf is evidently not a well-conducted epic. It may turn out to be no epic at all. But the puzzle still continues. In the most recent discourse upon this theme it still appears, toned down almost to a melancholy question-mark, as if this paradox had at last begun to afflict with weariness the thought that endeavours to support it. In the final peroration of his notable lecture on Folk-tale and History in Beowulf, given last year, Mr Girvan said:

Confessedly there is matter for wonder and scope for doubt, but we might be able to answer with complete satisfaction some of the questionings which rise in men’s minds over the poet’s presentment of his hero, if we could also answer with certainty the question why he chose just this subject, when to our modern judgment there were at hand so many greater, charged with the splendour and tragedy of humanity, and in all respects worthier of a genius as astonishing as it was rare in Anglo-Saxon England.

There is something irritatingly odd about all this. One even dares to wonder if something has not gone wrong with ‘our modern judgement’, supposing that it is justly represented. Higher praise than is found in the learned critics, whose scholarship enables them to appreciate these things, could hardly be given to the detail, the tone, the style, and indeed to the total effect of Beowulf. Yet this poetic talent, we are to understand, has all been squandered on an unprofitable theme: as if Milton had recounted the story of Jack and the Beanstalk in noble verse. Even if Milton had done this (and he might have done worse), we should perhaps pause to consider whether his poetic handling had not had some effect upon the trivial theme; what alchemy had been performed upon the base metal; whether indeed it remained base or trivial when he had finished with it. The high tone, the sense of dignity, alone is evidence in Beowulf of the presence of a mind lofty and thoughtful. It is, one would have said, improbable that such a man would write more than three thousand lines (wrought to a high finish) on matter that is really not worth serious attention; that remains thin and cheap when he has finished with it. Or that he should in the selection of his material, in the choice of what to put forward, what to keep subordinate ‘upon the outer edges’, have shown a puerile simplicity much below the level of the characters he himself draws in his own poem. Any theory that will at least allow us to believe that what he did was of design, and that for that design there is a defence that may still have force, would seem more probable.