Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

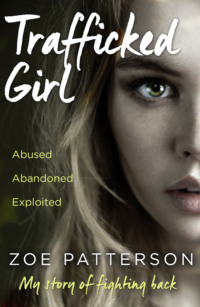

Buch lesen: "Trafficked Girl: Abused. Abandoned. Exploited. This Is My Story of Fighting Back."

Copyright

Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the family’s privacy.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperElement 2018

FIRST EDITION

© Zoe Patterson and Jane Smith 2018

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photograph (posed by a model) © Alexander Vinogradov/Trevillion

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Zoe Patterson and Jane Smith assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

Source ISBN: 9780008148041

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780008157586

Version: 2018-01-30

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Definition

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

About the Authors

About the Publisher

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

Definition

Care: (1) the provision of what is necessary for the health, welfare, maintenance, and protection of someone or something; (2) serious attention or consideration applied to doing something correctly or to avoid damage or risk.

Prologue

For many years, I believed that what happened to me when I was a little girl was my fault. I suppose if you tell someone almost anything over and over again from a very young age, they’ll grow up with it hardwired into their brain as a ‘fact’. Later, when they’re old enough to think for themselves, and if the fact has an objective or scientific basis, they might be able to disprove it. But that isn’t so easy to do if it’s something more subjective, particularly if it subsequently seems to be confirmed by other people and by apparently unconnected events.

The ‘fact’ I was told by my mother throughout my childhood and into adulthood was that I was to blame for all the horrible things that were done to me – many of which she actually did herself. So I was glad, although very scared, when the day came that I was taken into care. Maybe now, I thought, the bad stuff will stop happening, and then one day I’ll be able to live the sort of life I’ve always wanted to live – the sort of life my mum always said I didn’t deserve.

As things turned out, however, I was one of the unlucky ones for whom the care part of ‘being taken into care’ didn’t match any dictionary definition. In fact, what happened to me while I was living at Denver House was even worse than anything that had happened to me at home. Which made me think that maybe Mum had been right all along and I really was living the life I deserved.

Chapter 1

I had just woken up and was crossing the narrow landing at the top of the stairs when Mum came out of her bedroom. For some children, home is the only place they feel safe. For others, it’s the one place they know they aren’t. So when Mum took a step towards me, I felt the muscles in my body tense as I instinctively leaned away from her.

I was four years old, and I’d known since I was old enough to understand anything that I didn’t have to have done something wrong – or, at least, nothing I was aware of – for my mum to be angry with me. On this particular morning, however, instead of shouting at me and slapping me or pulling my hair, she just stood in the doorway of her bedroom and smiled.

It wasn’t a nice smile, the way I’d seen other mums smile at their kids when they came to pick them up from school. It was more like a nasty sneer, as if she knew something bad that I didn’t know and was relishing the prospect of telling me what it was. She didn’t say anything though, as I hovered on the landing, trying to decide whether my own anxious, tentative smile would annoy or appease her. She waited for me to take two hesitant steps down the stairs and then she pushed me.

‘Oh dear, grab the handrail,’ Mum called. But the concern in her voice was exaggerated and insincere, and she laughed out loud when I stumbled and fell, smacking my head into the wall at the bottom of the stairs.

I was still lying on the worn carpet in the hallway, shocked and disorientated, when Dad ran out of the living room and crouched down beside me.

‘Jesus Christ, Maggie,’ he shouted at Mum, who was standing smirking halfway down the stairs. ‘What happened? And what’s so funny? She’s hurt herself.’

‘Well, don’t blame me.’ Mum put her hands on her hips and glared angrily at us both. ‘It’s not my fault she’s clumsy and stupid. She tripped.’

For a moment I was forgotten as they shouted and swore at each other. So I sat up, touched the painful bump on the side of my head very gently with my fingertips, then examined the red mark on my elbow that I knew would soon develop into a bruise. It felt as though someone was pounding on the inside of my skull with something very heavy, and as the sound of my parents’ angry voices filled the air above me, I could feel tears stinging my eyes. But I was determined not to cry.

‘What happened, Zo?’ Dad put his hands under my arms and lifted me to my feet.

‘I told you, she tripped. Didn’t you?’ Mum was smiling the nasty smile again, although less broadly this time, maybe because she didn’t want Dad to see it as he guided me into the living room, where he sat me down in her chair saying, ‘I’ll get you some juice. That’ll make you feel better.’

It was rare for anyone to be kind to me at home, and although the memory of it makes me sad when I think about it today, I was too scared at the time to appreciate Dad’s concern for me, because I knew that as soon as he’d gone to work, Mum would find a way of making me pay for his attention.

I think Dad knew about some of the things she did to me, which was why he sometimes got angry with her, like he did that day. He certainly wasn’t aware of all of them though, as she was careful to hide her treatment of me, particularly when I was very young, and I didn’t ever say anything because I knew that if I did, my parents would shout and maybe fight with each other for a while, then Dad would go out and I’d be left alone with Mum.

So that time when she pushed me down the stairs is one of only very few occasions I can remember when Dad stood up for me. And although he did sometimes say nice things to me when I was a little girl, Mum always seemed to be standing behind him whenever he did, looking at me over his shoulder with a spiteful expression on her face that said quite clearly, ‘Just you wait until he’s gone to work.’

Some of the very few good memories I have of my early childhood are of standing at the front door waving to my dad as he left the house in the mornings. The happy feeling was always short-lived, however, and it would disappear as soon as the door closed, because I knew that, for the next few hours, it would just be Mum and me.

I loved both my parents when I was a little girl. Although my mum treated me very badly and I was afraid of her, I thought it was my fault she didn’t seem to love me and I desperately wanted her affection. With my dad it was different, and despite the fact that he very rarely actually did anything nice for me, he sometimes stood up for me, didn’t hit me and wasn’t nasty to me the way Mum was. So I really did love him, in the years before I learned to be frightened of him too.

I can’t recall one single instance of Mum ever being nice to me. She had only two sides to her when it came to her dealings with me – stern or nasty – and she could be very violent. In fact, the only time she ever touched me when I was a little girl was when she was pulling my hair or slapping, pinching, punching or kicking me, beating me with her fists or hitting me with the heel of her shoe, a book or, on one occasion, a baking tray. She didn’t ever hug me, or put her hands on me for any other reason except in anger. And it seemed that she was always angry with me, however hard I tried not to do anything that might irritate or antagonise her. It wasn’t until much later that I realised I didn’t really do anything to justify her cruel mind-games and vicious physical attacks. To my mum, I was simply a scapegoat, someone to blame for all the problems she had, many of which must have resulted from her own damaging childhood, although I didn’t find out about that until much later, when it was almost too late for me to be able to understand and accept the truth, which was that I had never really been the problem at all.

She would sometimes throw things at Dad too, or smash ornaments when they were fighting. But she never did to him – or to my brothers – any of the vicious things she did to me, I suppose for the same reason most bullies don’t pick fights with people who can fight back.

Fortunately, when I was alone in the house with her before I started going to nursery, when Dad was at work and my older brothers were at school, she spent almost all day every day in the kitchen. I don’t know whether she was already drinking at that time, but I think she probably was. So maybe that’s what she was doing in there while I was in the living room, trapped at a distance from her by the baby gate that blocked the doorway.

It was during that period of my childhood that Mum started refusing me access to the potty, and later to the toilet. I don’t know if she did it out of spite, to humiliate me, or if it was simply another way of exercising control over me. The baby gate was just a piece of wood my granddad had cut to size and attached across the doorway, but I wasn’t allowed to touch it, and never tried to again after the first time, when Mum beat me and shouted at me. So when I needed to use the potty, I would stand close to it and cry, while Mum either ignored me or watched me from the kitchen, impassively at first, then with increasing amusement when my discomfort turned to pain as I tried to hold it in. Then, when I soiled myself, as I always inevitably did, she would shout in my face and hit me, which made me believe that it really was my fault, however long she’d made me wait.

Sometimes, when I was a bit older and the baby gate had been removed, she would leave a tin plate in the middle of the kitchen floor for me to use as a toilet, as though I was a dog or a cat rather than a human child. I was probably four when she started doing it, and perfectly able to use the potty or go to the toilet by myself, but it was difficult doing it on a plate, particularly when she was watching me, as she often did, and I knew that if I misjudged it and let even the smallest drop spill over on to the floor, she would hit me.

Dad did shifts in a factory at that time and when he was working at night she’d quite often drink herself into a stupor, then fall asleep on the sofa. My brothers, Jake and Ben, who are nine and seven years older than me respectively, were old enough to put themselves to bed by the time I was born. But between the ages of three and five, I was often left downstairs on those nights and although I suppose I must have got some sleep, I don’t know when or where. I just remember wandering around the house in the dark, then seeing the sun shining in through a window and knowing that it was morning again. Mum would always make me get dressed quickly on those mornings, before my brothers woke up, and as she pulled my hair and hit me with her hairbrush she would warn me, ‘Don’t you dare tell Ben or Jake, or your dad, that you haven’t been to bed.’

I suppose those sleepless nights were the reason why I often fell asleep during the day when I started nursery school, and later in the reception class at primary school. In fact, I can remember on one occasion waking up in a state of near-panic when my teacher threw her shoe at me, then told me off for sleeping in class.

Mum did sometimes carry me up to bed when I’d fallen asleep. And sometimes she would drop me, then shout at me as I was tumbling down the stairs, ‘That was your fault,’ before stamping down to where I was lying in a crumpled heap, grabbing me by the arm and dragging me up to my bedroom, where she would almost throw me on to my bed. And on those occasions too, I would be determined not to cry, although I came very close to it whenever she said, in a spooky, sneering voice, ‘Watch out for wandering hands in your bed tonight.’ Then I would hear her laughing as she closed the door, shutting out all the light as she stomped back down the stairs.

I wasn’t allowed to get out of bed for any reason without Mum’s permission. So when I woke up from a nightmare, as I often did, I sometimes wet myself. The first time it happened, I cried and screamed for my mum, but no one came. So I lay for the rest of the night on the wet mattress and waited fearfully for the morning. She must have heard me whenever I called out in the night because she always seemed to know when she came into my room the next morning that the mattress would be wet, and after she’d yanked me out of bed, she’d drag me around the room by my hair, slapping me and shouting that I was worthless and stupid and did nothing but cause trouble for everyone. Then she would strip the wet sheet off my bed, take it downstairs and show it to my brothers, who would laugh with her and make fun of me.

We had a washing machine, so it wasn’t a huge deal having to wash a wet sheet, although perhaps it seemed like it to her, because when I finally stopped wetting the bed at the age of seven, she only ever washed my bedding once a year.

Mum never took me anywhere and she’d be angry on the rare occasions that Dad ever did, like the day when he got home after working the night shift and decided to take me with him to the supermarket. I think I was four years old, and I don’t know if I’d asked to go, or why Mum kept insisting on him leaving me at home. But the more she argued with him, the more determined he became, until eventually he shouted, ‘I’m taking her,’ then pushed me ahead of him out of the house before slamming the front door behind him.

Maybe their argument would have ended there if I hadn’t fallen asleep on the bus on the way back from the supermarket, and if Dad hadn’t told Mum it was her fault I was so tired and accused her – with more justification than I think he realised at the time – of not looking after me properly. So then they had a huge fight, while I tried to shut out the sound of their angry, hate-filled voices and not see what they were doing to each other.

I don’t think Mum’s reaction was because she was jealous. I think she just didn’t want me to have any positive experiences at all. And in the end she got her way, as she almost always did.

The only place Mum ever took me – and then only on very rare occasions – was to the supermarket. I certainly didn’t ever go to a cinema, a bowling alley or a park with her, and although my brothers had regular check-ups at the dentist, I never did. Even when I needed a haircut or new school uniform, it was my brother Ben who took me into town and paid for it with money Dad would give him. In fact, I only ever went to a playground once when I was a child.

It was on another occasion when Dad had taken me with him to the supermarket and we were on the way back that he said, ‘Come on, Zoe. Let’s go to the park.’ It was only a five-minute walk from our house, but although he’d been there many times with Jake and Ben when they were young, he’d never taken me. So I was very excited, and because I didn’t want him to change his mind, I didn’t ask him the question I was asking myself, which was, ‘What will Mum say if she finds out?’

When we got to the park, Dad took a white hankie out of his pocket and laid it carefully on the seat of the swing – ‘So that you don’t get your clothes dirty,’ he told me, which made me feel very special, like a princess. Then he pushed me, gently at first, until I got more confident and started shouting, ‘Higher! Higher!’

As all princesses know, however, there’s a wicked witch in every fairy tale and ours was waiting for us when we got home. Dad had only just opened the front door when she started shouting at him, asking what took us so long and demanding to know where we’d been. ‘We went to the fucking park,’ he told her, just before she hit him. Then he hit her and the row quickly escalated into a full-blown physical fight.

Whereas Dad had to be sober for at least a few hours every day when he was working at the factory, Mum had no such constraint and was eventually drinking more or less from the moment she woke up in the morning until the moment she fell asleep at night. And the more they both drank, the more frequent and violent their arguments became. So I spent many hours of my childhood listening to them shouting and hitting each other, and hearing Mum scream, ‘No! Stop it!’ when Dad lay on top of her and did something that made her struggle as she tried to push him off, which made me feel protective towards her, and guilty because I knew I couldn’t do anything to make him stop.

Looking back on it now, I’m glad Dad took me to the park that day, because although it ended in him and Mum having a horrible fight, he didn’t ever take me again. So at least I have that good memory of him pushing me on a swing before his attitude towards me began to change and it stopped being just Mum’s beatings that made me afraid to be in my own home.

Chapter 2

Jake and Ben used to bully me a lot when I was a child. But whereas Ben was sometimes nice to me, Jake never was, and he would often beat me and call me names like bitch, slag and slut, which I was too young to understand. I think he probably would have treated me the same way even if he hadn’t been encouraged by the fact that whenever Mum heard him tormenting me, she would laugh and join in, calling me ‘thunder thighs’ or saying I was ugly and fat, or that I had a hideous smile and a pig’s nose. I was just four years old when she bought me a pair of pig slippers – ‘Because they look just like you.’

The fact that Jake was nine and Ben was seven when I was born meant that by the time I was old enough to do anything, they were already leading their own lives and I had very little contact with either of them during my childhood, particularly with Jake. But although Mum was almost always angry with me, she rarely was with my brothers. So I believed her when she said there was something wrong with me and that I was the cause of all the rows and everything else that was stressful in her life. Everyone else did too, particularly when they saw how differently she treated my brothers, who were included as an integral part of the family and given pretty much free rein to do whatever they wanted whenever they wanted. What other explanation could there be of why a mother would love two of her children and so vehemently hate the other one?

Then, not long before I was due to start school, Mum had another baby.

I sometimes wonder what would have happened if my little brother Michael had been a girl – whether Mum would have hated her the way she hated me, or whether a little sister would have been included in the family the way Michael was when he was born. I often wonder if the physical contact I had with him when Mum wasn’t well and I used to have to give him his bottle was what made me able to identify and empathise with other people later, when I grew up, because he was the only human being I ever cuddled and hugged.

Mum had more or less recovered from her illness by the time I started school, so I was glad to have somewhere to escape to. I hadn’t ever played with other children before going to nursery – my older brothers only ever teased or bullied me – but despite having no experience of socialising, I got on well with the other kids and really enjoyed school, for the first few years at least, until what was happening at home made it difficult for me to cope with anything.

Despite being abused and excluded by my family, I accepted everything that happened at home as being normal. I think I was about ten years old by the time I even thought to compare my life and my brothers’ with any sense that the difference might be unfair. It was just the way things were: my brothers sat in the living room watching television and eating their meals with our parents, while I sat alone in my bedroom.

I spent many, many hours of my childhood on my own, sitting on the floor in the middle of my room staring at the walls. I wasn’t allowed to sit on the bed, move the furniture or play with any of the toys Mum arranged strategically on a shelf so that she’d know if I’d touched anything. I wasn’t even allowed to open the wardrobe or drawers until I was at least 11. Mum used to give me some clothes every morning and say, ‘This is what you’re wearing today.’ It was all about control, although obviously I didn’t realise that at the time. All I knew was that if I got so bored of just sitting there doing nothing that I managed to convince myself I’d be able to put something back exactly as I’d found it, she always knew. Then she’d shout at me and beat me, often with a half-smile on her face that reflected the enjoyment I think she got from punishing me.

There must have been many reasons for Mum’s behaviour, some of which I partially understand now, and some of which will, I’m sure, be locked away forever in the murky depths of her own psyche. One thing I did eventually become aware of is that she has obsessive-compulsive disorder, which got worse over the years, but which was already apparent in many of the things she did when I was a small child – although again, I didn’t realise that at the time. Some indications of it included the way she used to line things up on the bathroom windowsill – bottles and plastic containers of make-up all placed just so, and woe betide anyone who moved them – and the fact that, later, she always chose a cake bar and crisps to put in my school lunchbox that had a colour-matched wrapper and packet, which I used to think was an indication of the fact that she did care about me after all. Even today, she puts what she calls ‘traps’ around her house – an ornament or rug positioned at a particular angle, for example, or little stones lined up by her wheelie bin so that she’ll know if anyone has moved it, although I’m not sure why anyone would.

Not allowing me to sit on the bed after she’d made it, move anything or play with the few toys I had in my bedroom might have been aspects of OCD, if it hadn’t been for the fact that there were no such restrictions on my brothers. So I do think it was more of a control thing with me.

Usually, she would bring meals up to my room and I’d eat them there on my own, isolated from the rest of the family. I used to sit on the floor in my bedroom for hours, anxiously watching the door, waiting for it to burst open and for Mum to accuse me of doing something wrong, even when I wasn’t doing anything at all. I would sit on the floor in the living room too, on the rare occasions when I was allowed downstairs to watch television with the rest of my family. Sometimes, I’d hide behind the sofa, hoping they’d forget I was there, because I didn’t ever know why or when Mum might launch an attack on me.

In view of the way I was alienated and excluded from the family by my mum at every opportunity, it might seem odd to say that I’ve always had a strong sense of who I am, in some respects at least. The first time I think I ever became consciously aware of ‘me’ was when I was four years old and at nursery school. It was a very hot day and I was pushing a little lad around the playground on a toy tractor when he started pulling off his T-shirt. It seemed an obvious thing to do once he’d done it. So I took mine off too, and was startled when I realised a few seconds later that it was me the teacher was shouting at.

I can still remember how indignant I felt. Why was she picking on me, telling me to put my T-shirt on but not saying anything to the little boy? How was that fair? Although I’d learned not to expect fairness from my mum – and wouldn’t have dreamed of defying her in the same situation – I must have expected it from my teacher, because instead of doing as she told me, I bent down again and was just about to continue pushing the tractor when I saw her grab my T-shirt and start striding purposefully across the playground towards me. I don’t know what the reason was for my uncharacteristic defiance, but before she was halfway across the playground, I had taken to my heels.

Just a few days earlier, I’d watched an old black-and-white film with my brothers in which a man who was being chased slipped into the space between two buildings and his pursuer ran straight past. Although I was beyond the stage of covering my eyes with my hands and thinking no one could see me, I hadn’t quite understood how the incident in the film worked. So, as I was circling the nursery playground with my teacher in hot pursuit, I suddenly darted down the side of the building, flattened myself against the hot bricks and waited for her to run past. Then, a minute or two later, I resumed my game with the little boy, wearing my T-shirt and seething with righteous indignation.

It was an insignificant incident in itself, but I’ve held on to it – and a few similar memories – all these years because sometimes, when I seem to be in danger of forgetting, it reminds me who I am.

I don’t know what my dad was like before he married Mum. Maybe he was a completely different person and just got worn down by her until he began to accept her dysfunctional behaviour as normal. He was several years older than Mum and had been married and widowed for about ten years before they met. I think his first wife died suddenly and unexpectedly in her early twenties, by which time they already had a little boy, who went to live with Dad’s mum, apparently because that’s what his wife requested when she found out she was going to die.

Perhaps the reason Dad didn’t look after the little boy himself was because he wasn’t a very reliable parent even before he met my mum. Or maybe his wife knew he would fall apart when she died, because I know he found it really difficult trying to deal with her death and was still working long hours so that he didn’t have to face it ten years later, when he met Mum. Perhaps that also explained why he made what turned out to be the huge mistake of ignoring the warning ‘marry in haste, repent at leisure’ and married her just two weeks later. She was still living with her parents at the time, so for her it was a means of escaping, which I now know she had good reason to want to do.

I don’t know how often Dad saw his first son, Ian, after he and Mum got married, but she more or less put a stop to any contact they did have when Jake was born – and with the rest of his family too, who we rarely saw when I was growing up.

Dad used to love singing karaoke at the pub and one day he came home with a karaoke machine he’d bought for a few pounds when they were throwing it out. Mum just sat there scowling when he took it into the living room and plugged it in, and after he’d sung a couple of songs himself, he told me to sing some of the nursery rhymes I’d just learnt at nursery school. ‘I’m going to record them,’ he said. ‘Then, when you’re an old lady, you can listen to them and remember what you used to sound like when you were four.’

I was too young to understand the concept of one day being old, like my nan. But I can remember feeling really pleased when Dad said I had a nice voice, then laughed and added, ‘You must have inherited it from me,’ which made Mum scowl even more.

The only other happy childhood memory I have is of another day when I was four and Dad took me to a big garden that was open to the public, where there was a lake and a real elephant that he paid for me to sit on and have my photograph taken. I can still remember how rough the elephant’s skin felt where it touched my bare legs.

Maybe Dad did other things with me on other days as well, but I can’t remember any of them now. I just remember that I loved him and that although he didn’t often do anything positive to make my life better, he wasn’t ever violent or mean to me when I was a little girl.

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.