Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

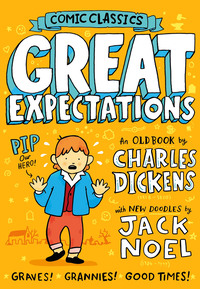

Buch lesen: "Comic Classics: Great Expectations"

With thanks/apologies to Charles Dickens

ORIGINAL STORY BY CHARLES DICKENS ABRIDGED BY LIZ BANKES DESIGNED AND ILLUSTRATED BY JACK NOEL EDITED BY LIZ BANKES WITH LUCY COURTENAY ART-DIRECTION BY LIZZIE GARDINER WITH MARGARET HOPE PRODUCTION CHARLOTTE COOPER AND TEAM FOREIGN RIGHTS JULIETTE CLARK AND TEAM SALES JAS FYFE, DAN DOWNHAM AND TEAM PUBLISHER ALI DOUGAL AGENT CLAIRE WILSON WITH MIRIAM TOBIN AT RCW SPECIAL THANKS TO CHARLOTTE KNIGHT

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Egmont UK Limited

2 Minster Court, 10th floor, London EC3R 7BB

Text and illustrations copyright © 2020 Jack Noel

The moral rights of the author and illustrator have been asserted

First e-book edition 2020

ISBN 978 1 4052 9404 1

Ebook ISBN 978 1 4052 9405 8

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at the time of going to print. However, Egmont is not responsible for content hosted by third parties. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are supervised when using the internet.

Egmont takes its responsibility to the planet and its inhabitants very seriously. We aim to use papers from well-managed forests run by responsible suppliers.

CONTENTS

Cover

Dedication and Copyright

Title Page

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

CHAPTER XV

CHAPTER XVI

CHAPTER XVII

CHAPTER XVIII

CHAPTER XIX

CHAPTER XX

Back series promotional page

MY FATHER’S FAMILY name being Pirrip, and my Christian name Philip, my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than PIP.

So, I called myself Pip, and came to be called PIP.

I never saw my father or my mother, and never saw any likeness of either of them (for their days were long before the days of photographs).

My first ideas regarding what they were like were unreasonably derived from their tombstones.

The shape of the letters on my father’s tombstone gave me an odd idea that he was a square, stout, dark man, with curly black hair.

From my mother’s, I drew a childish conclusion that she was freckled and sickly.

AND SO MY STORY BEGINS

It was a memorable raw afternoon towards evening.

This bleak place overgrown with nettles was the churchyard;

where

PHILIP PIRRIP,

late of this parish,

and also

GEORGIANA

wife of the above,

were dead

and buried.

The dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes.

The low leaden line beyond was the river;

and that the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing was the sea.

And the small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry, was PIP.

A man with no hat, and with broken shoes, and with an old rag tied round his head. A man who had been soaked in water, and smothered in mud, and lamed by stones, and cut by flints, and stung by nettles, and torn by briars; who limped, and shivered, and glared, and growled; and whose teeth chattered in his head as he seized me by the chin.

“Tell us your name!” said the man. “QUICK!”

“Pip, sir.”

“Once more,” said the man, staring at me.

“Pip. Pip, sir.”

I pointed to where our village lay, a mile or more from the church.

“Who d’ye live with . . . supposin’ I LET you live, which I haven’t made up my mind about?”

“I live with my sister, sir – Mrs Joe Gargery – wife of Joe Gargery, the blacksmith, sir.”

said he. And looked down at his leg.

Then he came closer, took me by both arms, and tilted me back as far as he could hold me. “NOW LOOKEE HERE,” he said,

“You know what a FILE is?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And you know what WITTLES is?”

“Yes, sir.”

After each question he tilted me over a little more.

I said that I would get him the file, and I would get him what broken bits of food I could, and bring them to him early in the morning.

I said so, and he put me down.

He hugged his shuddering body in both his arms, as if to hold himself together, and limped towards the low church wall.

As I saw him go, picking his way among the nettles and among the brambles, he looked as if he were avoiding the hands of the dead people,

But now I was frightened again, and I ran home without stopping.

MY SISTER, MRS Joe Gargery, was more than twenty years older than I, and had established a great reputation with herself and the neighbours because she had brought me up ‘by hand’. Not knowing what the expression meant, and knowing her to have a hard and heavy hand, and to be much in the habit of laying it upon her husband as well as upon me, I supposed that Joe Gargery and I were both brought up BY HAND.

Joe Gargery was a mild, good-natured, sweet-tempered, easy-going, foolish, dear fellow, a sort of Hercules in strength, and also in weakness.

My sister had such a prevailing redness of skin that I sometimes used to wonder whether it was possible she washed herself with a nutmeg-grater instead of soap.

Joe’s forge adjoined our house, which was a wooden house. When I ran home from the churchyard, the forge was shut up, and Joe was sitting alone in the kitchen.

“and what’s worse, she’s got TICKLER with her.”

“She sat down,” said Joe, “and she got up, and she made a grab at Tickler, and she RAMPAGED out. That’s what she did,” said Joe. “She RAMPAGED OUT, PIP.”

“Has she been gone long, Joe?”

“Well,” said Joe, glancing up at the clock, “she’s been on the Rampage, this last spell, about five minutes, Pip.

SHE’S A COMING! Get behind the door, old chap.”

My sister, throwing the door wide open, and finding an obstruction behind it, immediately applied Tickler to its further investigation. She concluded by throwing me at Joe, who passed me on into the chimney and quietly fenced me up there with his great leg.

repeated my sister.

“If it warn’t for me you’d have been to the churchyard long ago, and stayed there.

WHO BROUGHT YOU UP BY HAND?”

“You did,” said I.

“And why did I do it, I should like to know?” exclaimed my sister.

I whimpered, “I don’t know.”

“I don’t!” said my sister. “I’d never do it again! I know that. It’s bad enough to be a blacksmith’s wife without being your mother.”

I looked at the fire. The fugitive out on the marshes with the ironed leg, the file, the food, and the dreadful pledge I was under, rose before me in the avenging coals.

“Hah!” said Mrs Joe, restoring Tickler to his station.

| Joe was about to take another bite, when his eye fell on me, and he saw that my bread and butter was gone. |  |

| “What’s the matter now?” said my sister, smartly, as she put down her cup. |

| Joe shook his head. |  |

| “What’s the matter now?” repeated my sister, more sharply than before. |

She pounced on Joe while I sat, looking guiltily on. “Now, perhaps you’ll mention what’s the matter,” said my sister, out of breath,

“YOU STARING GREAT STUCK PIG.”

Joe looked at her in a helpless way, then took a helpless bite, and looked at me again.

“Been bolting his food, has he?” cried my sister.

She made a dive at me, and fished me up by the hair, saying nothing more than the awful words,

The guilty knowledge that I was going to rob Mrs Joe almost drove me out of my mind.

Then, as the marsh winds made the fire glow and flare, I thought I heard the voice outside, of the man with the iron on his leg, declaring that he must be fed NOW.

It was Christmas Eve, and I had to stir the pudding for next day, with a copper-stick, from seven to eight by the clock.

“Hark!” said I, when I had done my stirring, and was taking a final warm in the chimney corner before being sent up to bed.

“There was a convict escaped last night,” said Joe. “And they fired warning of him. And now it appears they’re firing warning of another.”

interposed my sister, frowning at me, “what a questioner he is.

Ask no questions, and you’ll be told no lies.”

Joe opened his mouth very wide, and to put it into the form of a word that looked to me like ‘SULKS’.

Therefore, I pointed to my sister, and mouthed, “her?”

“From the HULKS!” exclaimed my sister.

“Oh-H!” said I, looking at Joe. “Hulks!”

Joe gave a reproachful cough, as much as to say, “Well, I told you so.”

“And please, what’s Hulks?” said I.

“That’s the way with this boy!” exclaimed my sister. “Answer him one question, and he’ll ask you a dozen directly. Hulks are prison-ships, right across the marshes.”

| “Who’s put into prison-ships, and why are they put there?” said I, with quiet desperation. It was too much for Mrs Joe, who immediately rose. “I didn’t bring you up BY HAND to badger people’s lives out. |  |

| People are put in the Hulks because they MURDER, |  |

| and because they ROB, |

| and FORGE, |  |

and do all sorts of BAD; and they always begin by ASKING QUESTIONS.

I went upstairs in the dark, with my head tingling from Mrs Joe’s last words. I was clearly on my way to the hulks. I had begun by asking questions, and I was going to rob Mrs Joe . . .

I was afraid to sleep for I knew that at the first faint dawn of morning I must rob the pantry.

I got up and went downstairs; every floorboard upon the way, and every crack in every board calling after me.

In the pantry, I had no time to spare.

There was a door in the kitchen to the forge; I unlocked and unbolted that door, and got a file from among Joe’s tools. Then I put the fastenings as I had found them, opened the door at which I had entered when I ran home last night, shut it, and ran for the misty marshes.