Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

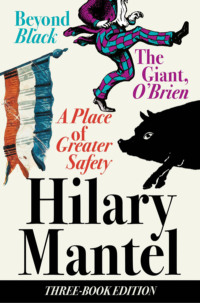

Buch lesen: "Three-Book Edition: A Place of Greater Safety; Beyond Black; The Giant O’Brien"

Hilary Mantel

Three-Book Edition

A Place of Greater Safety

Beyond Black

The Giant, O’Brien

About the Author

Hilary Mantel is the author of thirteen books, including A Place of Greater Safety, Beyond Black, and the memoir Giving Up the Ghost. Her two most recent novels, Wolf Hall and its sequel Bring Up the Bodies, have both been awarded the Man Booker Prize. Bring Up the Bodies also won the Costa Book of the Year.

Also by Hilary Mantel

Bring Up the Bodies

Wolf Hall

Beyond Black

Every Day is Mother’s Day

Vacant Possession

Eight Months on Ghazzah Street

Fludd

A Place of Greater Safety

A Change of Climate

An Experiment in Love

The Giant, O’Brien

Learning to Talk

Non-fiction

Giving Up the Ghost

Table of Contents

Title Page

About the Author

Also by Hilary Mantel

A Place of Greater Safety

Beyond Black

The Giant, O’Brien

Excerpt from Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

Copyright

About the Publisher

A Place of Greater Safety

Hilary Mantel

A Place of Greater Safety

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Author’s Note

Cast of Characters

Map of Revolutionary Paris

PART ONE

I. Life as a Battlefield (1763–1774)

II. Corpse-Candle (1774–1780)

III. At Maître Vinot’s (1780)

PART TWO

I. The Theory of Ambition (1784–1787)

II. Rue Condé: Thursday Afternoon (1787)

III. Maximilien: Life and Times (1787)

IV. A Wedding, a Riot, a Prince of the Blood (1787–1788)

V. A New Profession (1788)

VI. Last Days of Titonville (1789)

VII. Killing Time (1789)

PART THREE

I. Virgins (1789)

II. Liberty, Gaiety, Royal Democracy (1790)

III. Lady’s Pleasure (1791)

IV. More Acts of the Apostles (1791)

PART FOUR

I. A Lucky Hand (1791)

II. Danton: His Portrait Made (1791)

III. Three Blades, Two in Reserve (1791–1792)

IV. The Tactics of a Bull (1792)

V. Burning the Bodies (1792)

PART FIVE

I. Conspirators (1792)

II. Robespierricide (1792)

III. The Visible Exercise of Power (1792–1793)

IV. Blackmail (1793)

V. A Martyr, a King, a Child (1793)

VI. A Secret History (1793)

VII. Carnivores (1793)

VIII. Imperfect Contrition (1793)

IX. East Indians (1793)

X. The Marquis Calls (1793)

XI. The Old Cordeliers (1793–1794)

XII. Ambivalence (1794)

XIII. Conditional Absolution (1794)

Note

Dedication

To Clare Boylan

Author’s Note

THIS IS A NOVEL about the French Revolution. Almost all the characters in it are real people and it is closely tied to historical facts – as far as those facts are agreed, which isn’t really very far. It is not an overview or a complete account of the Revolution. The story centres on Paris; what happens in the provinces is outside its scope, and so for the most part are military events.

My main characters were not famous until the Revolution made them so, and not much is known about their early lives. I have used what there is, and made educated guesses about the rest.

This is not, either, an impartial account. I have tried to see the world as my people saw it, and they had their own prejudices and opinions. Where I can, I have used their real words – from recorded speeches or preserved writings – and woven them into my own dialogue. I have been guided by a belief that what goes on to the record is often tried out earlier, off the record.

There is one character who may puzzle the reader, because he has a tangential, peculiar role in this book. Everyone knows this about Jean-Paul Marat: he was stabbed to death in his bath by a pretty girl. His death we can be sure of, but almost everything in his life is open to interpretation. Dr Marat was twenty years older than my main characters, and had a long and interesting pre-revolutionary career. I did not feel that I could deal with it without unbalancing the book, so I have made him the guest star, his appearances few but piquant. I hope to write about Dr Marat at some future date. Any such novel would subvert the view of history which I offer here. In the course of writing this book I have had many arguments with myself, about what history really is. But you must state a case, I think, before you can plead against it.

The events of the book are complicated, so the need to dramatize and the need to explain must be set against each other. Anyone who writes a novel of this type is vulnerable to the complaints of pedants. Three small points will illustrate how, without falsifying, I have tried to make life easier.

When I am describing pre-revolutionary Paris, I talk about ‘the police’. This is a simplification. There were several bodies charged with law enforcement. It would be tedious, though, to hold up the story every time there is a riot, to tell the reader which one is on the scene.

Again, why do I call the Hôtel de Ville ‘City Hall’? In Britain, the term ‘Town Hall’ conjures up a picture of comfortable aldermen patting their paunches and talking about Christmas decorations or litter bins. I wanted to convey a more vital, American idea; power resides at City Hall.

A smaller point still: my characters have their dinner and their supper at variable times. The fashionable Parisian dined between three and five in the afternoon, and took supper at ten or eleven o’clock. But if the latter meal is attended with a degree of formality, I’ve called it ‘dinner’. On the whole, the people in this book keep late hours. If they’re doing something at three o’clock, it’s usually three in the morning.

I am very conscious that a novel is a cooperative effort, a joint venture between writer and reader. I purvey my own version of events, but facts change according to your viewpoint. Of course, my characters did not have the blessing of hindsight; they lived from day to day, as best they could. I am not trying to persuade my reader to view events in a particular way, or to draw any particular lessons from them. I have tried to write a novel that gives the reader scope to change opinions, change sympathies: a book that one can think and live inside. The reader may ask how to tell fact from fiction. A rough guide: anything that seems particularly unlikely is probably true.

Cast of Characters

PART I

In Guise:

Jean-Nicolas Desmoulins, a lawyer

Madeleine, his wife

Camille, his eldest son (b. 1760)

Elisabeth, his daughter

Henriette, his daughter (died aged nine)

Armand, his son

Anne-Clothilde, his daughter

Clément, his youngest son

Adrien de Viefville

Jean-Louis de Viefville} their snobbish relations

The Prince de Condé, premier nobleman of the district and a client of Jean-Nicolas Desmoulins

In Arcis-sur-Aube:

Marie-Madeleine Danton, a widow, who marries

Jean Recordain, an inventor

Georges-Jacques, her son (b. 1759)

Anne Madeleine, her daughter

Pierrette, her daughter

Marie-Cécile, her daughter, who becomes a nun

In Arras:

François de Robespierre, a lawyer

Maximilien, his son (b. 1758)

Charlotte, his daughter

Henriette, his daughter (died aged nineteen)

Augustin, his younger son

Jacqueline, his wife, née Carraut, who dies after giving birth to a fifth child

Grandfather Carraut, a brewer

Aunt Eulalie

Aunt Henriette} François de Robespierre’s sisters

In Paris, at Louis-le-Grand:

Father Poignard, the principal – a liberal minded man

Father Proyart, the deputy principal – not at all a liberal-minded man

Father Herivaux, a teacher of classical languages

Louis Suleau, a student

Stanislas Fréron, a very well-connected student, known as ‘Rabbit’

In Troyes:

Fabre d’Églantine, an unemployed genius

PART II

In Paris:

Maître Vinot, a lawyer in whose chambers Georges-Jacques Danton is a pupil

Maître Perrin, a lawyer in whose chambers Camille Desmoulins is a pupil

Jean-Marie Hérault de Séchelles, a young nobleman and legal dignitary

François-Jérôme Charpentier, a café owner and Inspector of Taxes

Angélique (Angelica) his Italian wife

Gabrielle, his daughter

Françoise-Julie Duhauttoir, Georges-Jacques Danton’s mistress

At the rue Condé:

Claude Duplessis, a senior civil servant

Annette, his wife

Adèle

Lucile} his daughters

Abbé Laudréville, Annette’s confessor, a go-between

In Guise:

Rose-Fleur Godard, Camille Desmoulins’s fiancée

In Arras:

Joseph Fouché, a teacher, Charlotte de Robespierre’s beau

Lazare Carnot, a military engineer, a friend of Maximilien de Robespierre

Anaïs Deshorties, a nice girl whose relatives want her to marry Maximilien de Robespierre

Louise de Kéralio, a novelist: who goes to Paris, marries François Robert and edits a newspaper

Hermann, a lawyer, a friend of Maximilien de Robespierre

The Orléanists:

Philippe, Duke of Orléans, cousin of King Louis XVI

Félicité de Genlis, an author – his ex-mistress, now Governor of his children

Charles-Alexis Brulard de Sillery, Comte de Genlis – Félicité’s husband, a former naval officer, a gambler

Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, a novelist, the Duke’s secretary

Agnès de Buffon, the Duke’s mistress

Grace Elliot, the Duke’s ex-mistress, a spy for the British Foreign Office

Axel von Fersen, the Queen’s lover

At Danton’s chambers:

Jules Paré, his clerk

François Deforgues, his clerk

Billaud-Varennes, his part-time clerk, a man of sour temperament

At the Cour du Commerce:

Mme Gély, who lives upstairs from Georges-Jacques and Gabrielle Danton

Antoine, her husband

Louise, her daughter

Catherine

Marie} the Dantons’ servants

Legendre, a master butcher, a neighbour of the Dantons

François Robert, a lecturer in law: marries Louise de Kéralio, opens a delicatessen, and later becomes a radical journalist

René Hébert, a theatre box-office clerk

Anne Théroigne, a singer

In the National Assembly:

Antoine Barnave, a deputy: at first a radical, later a royalist

Jérôme Pétion, a radical deputy, later called a ‘Brissotin’

Dr Guillotin, an expert on public health

Jean-Sylvain Bailly, an astronomer, later Mayor of Paris.

Honoré-Gabriel Riquetti, Comte de Mirabeau, a renegade aristocrat sitting for the Commons, or Third Estate

Teutch, Mirabeau’s valet

Clavière

Dumont

Duroveray} His ‘slaves’, Genevan politicans in exile

Jean-Pierre Brissot, a journalist

Momoro, a printer

Réveillon, owner of a wallpaper factory

Hanriot, owner of a saltpetre works

De Launay, Governor of the Bastille

PART III

M. Soulès, temporary Governor of the Bastille

The Marquis de Lafayette, Commander of the National Guard

Jean-Paul Marat, a journalist, editor of the People’s Friend

Arthur Dillon, Governor of Tobago and a general in the French army; a friend of Camille Desmoulins

Louis-Sébastien Mercier, a well-known author

Collot d’Herbois, a playwright

Father Pancemont, a truculent priest

Father Bérardier, a gullible priest

Caroline Rémy, an actress

Père Duchesne, a furnace-maker: fictitious alter ego of René. Hébert, box-office clerk turned journalist

Antoine Saint-Just, a disaffected poet, acquainted with or related to Camille Desmoulins

Jean-Marie Roland, an elderly ex-civil servant

Manon Roland, his young wife, a writer

François-Léonard Buzot, a deputy, member of the Jacobin Club and friend of the Rolands

Jean-Baptiste Louvet, a novelist, Jacobin, friend of the Rolands

PART IV

At the rue Saint-Honoré:

Maurice Duplay, a master carpenter

Françoise Duplay, his wife

Eléonore, an art student, his eldest daughter

Victoire, his daughter

Elisabeth (Babette), his youngest daughter

Charles Dumouriez, a general, sometime Foreign Minister

Antoine Fouquier-Tinville, a lawyer; Camille Desmoulins’s cousin

Jeanette, the Desmoulins’s servant

PART V

Politicians described as ‘Brissotins’ or ‘Girondins’:

Jean-Pierre Brissot, a journalist

Jean-Marie and Manon Roland

Pierre Vergniaud, member of the National Convention, famous as an orator

Jérôme Pétion

François-Léonard Buzot

Jean-Baptiste Louvet

Charles Barbaroux, a lawyer from Marseille and many others

Albertine Marat, Marat’s sister

Simone Evrard, Marat’s common-law wife

Defermon, a deputy, sometime President of the National Convention

Jean-François Lacroix, a moderate deputy: goes ‘on mission’ to Belgium with Danton in 1792 and 1793

David, a painter

Charlotte Corday, an assassin

Claude Dupin, a young bureaucrat who proposes marriage to Louise Gély, Danton’s neighbour

Souberbielle, Robespierre’s doctor

Renaudin, a violin-maker, prone to violence

Father Kéravenen, an outlaw priest

Chauveau-Lagarde, a lawyer: defence council for Marie-Antoinette

Philippe Lebas, a left-wing deputy: later a member of the Committee of General Security, or Police Committee; marries Babette Duplay

Vadier, known as ‘the Inquisitor’, a member of the Police Committee

Implicated in the East India Company fraud:

Chabot, a deputy, ex-Capuchin friar

Julien, a deputy, former Protestant pastor

Proli, secretary to Hérault de Séchelles, and said to be an Austrian spy

Emmanuel Dobruska and Siegmund Gotleb, known as Emmanuel and Junius Frei: speculators

Guzman, a minor politician, Spanish-born

Diedrichsen, a Danish ‘businessman’

Abbé d’Espanac, a crooked army contractor

Basire

Delaunay} deputies

Citizen de Sade, a writer, formerly a marquis

Pierre Philippeaux, a deputy: writes a pamphlet against the government during the Terror

Some members of the Committee of Public Safety:

Saint-André

Barère

Couthon, a paraplegic, a friend of Robespierre

Robert Lindet, a lawyer from Normandy, a friend of Danton

Etienne Panis, a left-wing deputy, a friend of Danton

At the trial of the Dantonists:

Hermann (once of Arras), President of the Revolutionary

Tribunal

Dumas, his deputy

Fouquier-Tinville, now Public Prosecutor

Fleuriot

Liendon} prosecution lawyers

Fabricius Pâris, Clerk of the Court

Laflotte, a prison informer

Henri Sanson, public executioner

Map of Revolutionary Paris

PART ONE

LOUIS XV is named the Well-Beloved. Ten years pass. The same people believe the Well-Beloved takes baths of human blood…Avoiding Paris, ever shut up at Versailles, he finds even there too many people, too much daylight. He wants a shadowy retreat…

In a year of scarcity (they were not uncommon then) he was hunting as usual in the Forest of Sénart. He met a peasant carrying a bier and inquired, ‘Whither he was conveying it?’ ‘To such a place.’ ‘For a man or a woman?’ ‘A man.’ ‘What did he die of?’ ‘Hunger.’

Jules Michelet

I. Life as a Battlefield (1763–1774)

NOW THAT THE DUST has settled, we can begin to look at our situation. Now that the last red tile has been laid on the roof of the New House, now that the marriage contract is four years old. The town smells of summer; not very pleasant, that is, but the same as last year, the same as the years to follow. The New House smells of resin and wax polish; it has the sulphurous odour of family quarrels brewing.

Maître Desmoulins’s study is across the courtyard, in the Old House that fronts the street. If you stand in the Place des Armes and look up at the narrow white façade, you can often see him lurking behind the shutters on the first floor. He seems to stare down into the street; but he is miles away, observers say. This is true, and his location is very precise. Mentally, he is back in Paris.

Physically, at this moment, he is on his way upstairs. His three-year-old son is following him. As he expects the child to be under his feet for the next twenty years, it does not profit him to complain about this. Afternoon heat lies over the streets. The babies, Henriette and Elisabeth, are asleep in their cribs. Madeleine is insulting the laundry girl with a fluency and venom that belie her gravid state, her genteel education. He closes the door on them.

As soon as he sits down at his desk, a stray Paris thought slides around his mind. This happens often. He indulges himself a little: places himself on the steps of the Châtelet court with a hard-wrung acquittal and a knot of congratulatory colleagues. He gives his colleagues names and faces. Where is Perrin this afternoon? And Vinot? Now he goes up twice a year, and Vinot – who used to discuss his Life Plan with him when they were students – had walked right past him in the Place Dauphine, not knowing him at all.

That was last year, and now it is August, in the year of Grace 1763. It is Guise, Picardy; he is thirty-three years old, husband, father, advocate, town councillor, official of the bailiwick, a man with a large bill for a new roof.

He takes out his account books. It is only two months ago that Madeleine’s family came up with the final instalment of the dowry. They pretended – knowing that he could hardly disabuse them – that it was a kind of flattering oversight; that a man in his position, with steady work coming in, would hardly notice the last few hundred.

This was a typical de Viefville trick, and he could do nothing about it. They hammered him to the family mast while, quivering with embarrassment, he handed them the nails. He’d come home from Paris at their behest, to set things up for Madeleine. He hadn’t known that she’d be turned thirty before her family considered his situation even half-way satisfactory.

What de Viefvilles do, they run things: small towns, large legal practices. There are cousins all over the Laon district, all over Picardy: a bunch of nerveless crooks, always talking. One de Viefville is Mayor of Guise, another is a member of that august judicial body, the Parlement of Paris. De Viefvilles generally marry Godards; Madeleine is a Godard, on her father’s side. The Godards’ name lacks the coveted particle of nobility; for all that, they tend to get on in life, and when you attend in Guise and environs a musical evening or a funeral or a Bar Association dinner, there is always one present to whom you can genuflect.

The ladies of the family believe in annual production, and Madeleine’s late start hardly deters her. Hence the New House.

This child was his eldest, who now crossed the room and scrambled into the window-seat. His first reaction, when the newborn was presented: this is not mine. The explanation came at the christening, from the grinning uncles and cradle-witch aunts: aren’t you a little Godard then, isn’t he a little Godard to his fingertips? Three wishes, Jean-Nicolas thought sourly: become an alderman, marry your cousin, prosper like a pig in clover.

The child had a whole string of names, because the godparents could not agree. Jean-Nicolas spoke up with his own preference, whereupon the family united: you can call him Lucien if you like, but We shall call him Camille.

It seemed to Desmoulins that with the birth of this first child he had become like a man floundering around in a sucking swamp, with no glimmering of rescue. It was not that he was unwilling to assume responsibilities; he was simply overwhelmed by the perplexities of life, paralysed by the certainty that there was nothing constructive to be done in any given situation. The child particularly presented an insoluble problem. It seemed inaccessible to the processes of legal reasoning. He smiled at it, and it learned to smile back: not with the amicable toothless grin of most infants, but with what he took to be a flicker of amusement. Then again, he had always understood that the eyes of small babies did not focus properly, but this one – and no doubt it was entirely his imagination – seemed to look him over rather coolly. This made him uneasy. He feared, in his secret heart, that one day in company the baby would sit up and speak; that it would engage his eyes, appraise him, and say, ‘You prick.’

Standing on the window-seat now, his son leans out over the square, and gives him a commentary on who comes and goes. There is the curé, there is M. Saulce. Now comes a rat. Now comes M. Saulce’s dog; oh, poor rat.

‘Camille,’ he says, ‘get down from there, if you drop out on to the cobbles and damage your brain you will never make an alderman. Though you might, at that; who would notice?’

Now, while he adds up the tradesmen’s bills, his son leans out of the window as far as he can, looking for further carnage. The curé recrosses the square, the dog falls asleep in the sun. A boy comes with a collar and chain, subdues the dog and leads it home. At last Jean-Nicolas looks up. ‘When I have paid for the roof,’ he says, ‘I shall be flat broke. Are you listening to me? While your uncles continue to withhold from me all but the dregs of the district’s legal work, I cannot get by from month to month without making inroads into your mother’s dowry, which is supposed to pay for your education. The girls will be all right, they can do needlework, perhaps people will marry them for their personal charms. We can hardly expect you to get on in the same way.’

‘Now comes the dog again,’ his son says.

‘Do as I tell you and come in from the window. And do not be childish.’

‘Why not?’ Camille says. ‘I’m a child, aren’t I?’

His father crosses the room and scoops him up, prising his fingers away from the window frame to which he clings. His eyes widen in astonishment at being carried off by this superior strength. Everything astonishes him: his father’s diatribes, the speckles on an eggshell, women’s hats, ducks on the pond.

Jean-Nicolas carries him across the room. When you are thirty, he thinks, you will sit at this desk and, turning from your account books to the piffling local business on which you are employed, you will draft, for perhaps the tenth time in your career, a deed of mortgage on the manor house at Wiège; and that will wipe the look of surprise off your face. When you are forty, and greying, and worried sick about your eldest son, I shall be seventy. I shall sit in the sunshine and watch the pears ripen on the wall, and M. Saulce and the curé will go by and touch their hats to me.

WHAT DO WE THINK about fathers? Important, or not? Here is what Rousseau says:

The oldest of all societies, and the only natural one, is that of the family, yet children remain tied to their father by nature only as long as they need him for their preservation…The family may perhaps be seen as the first model of political society. The head of the state bears the image of the father, the people the image of his children.

So here are some more family stories.

M. DANTON had four daughters: younger than these, one son. He had no attitude to this child, except perhaps relief at its gender. Aged forty, M. Danton died. His widow was pregnant, but lost the child.

In later life, the child Georges-Jacques thought he remembered his father. In his family the dead were much discussed. He absorbed the content of these conversations and transmuted them into what passed for memory. This serves the purpose. The dead don’t come back, to quibble or correct.

M. Danton had been clerk to one of the local courts. There was a little money, some houses, some land. Madame found herself coping. She was a bossy little woman who approached life with her elbows out. Her sisters’ husbands came by every Sunday, and gave her advice.

Subsequently, the children ran wild. They broke people’s fences and chased sheep and committed various other rural nuisances. When accosted, they talked back. Children of other families they threw in the river.

‘That girls should be like that!’ said M. Camus, Madame’s brother.

‘It isn’t the girls,’ Madame said. ‘It’s Georges-Jacques. But look, they have to survive.’

‘But this is not some jungle,’ M. Camus said. ‘It is not Patagonia. It is Arcis-sur-Aube.’

Arcis is green; the land around is flat and yellow. Life goes on at a steady pace. M. Camus eyes the child, where outside the window he throws stones at the barn.

‘The boy is savage and quite unnecessarily large,’ he says. ‘Why has he got a bandage round his head?’

‘Why should I tell you? You’ll only bad-mouth him.’

Two days ago, one of the girls had brought him home in the early warm dusk. They had been in the bull’s field, she said, playing at Early Christians. This was perhaps the pious gloss Anne Madeleine put on the matter; it was possible of course that not all the Church’s martyrs agreed to be gored, and that some, like Georges-Jacques, went armed with pointed sticks. Half his face was ripped up from the bull’s horn. Panic-stricken, his mother had taken his head in her hands and shoved the flesh together and hoped against hope it would stick. She bandaged it tightly and put another bandage around his head to cover the bumps and cuts on his forehead. For two days, with a helmeted, aggressive air, he stayed in the house and moped. He complained that he had a headache. This was the third day.

Twenty-four hours after M. Camus had taken his leave, Mme Danton stood at the same window and watched – as if in a dazed, dreadful repeating dream – while her son’s remains were manhandled across the fields. A farm labourer carried the heavy body in his arms; she could see how his knees bent under the dead-weight. There were two dogs running after him with their tails between their legs; trailing behind came Anne Madeleine, bawling with rage and despair.

When she reached them she saw that the man had tears in his eyes. ‘That bloody bull will have to be slaughtered,’ he said. They went into the kitchen. There was blood everywhere. It was all over the man’s shirt, the dogs’ fur, Anne Madeleine’s apron and even her hair. It went all over the floor. She cast around for something – a blanket, a clean cloth – on which to lay the corpse of her only son. The labourer, exhausted, swayed against the wall, marking the plaster with a long rust-coloured streak.

‘Put him on the floor,’ she said.

When his cheek touched the cold tiles of the floor, the child moaned softly; only then did she realize he wasn’t dead. Anne Madeleine was repeating the De profundis in a monotone: ‘From the morning watch even until night: let Israel hope in the Lord.’ Her mother hit her across the ear to shut her up. Then a chicken flew in at the door and got on her foot.

‘Don’t strike the girl,’ the labourer said. ‘She pulled him out from under its feet.’

Georges-Jacques opened his eyes and vomited. They made him lie still, and felt his limbs for fractures. His nose was broken. He breathed bubbles of blood. ‘Don’t blow your nose,’ the man said, ‘or your brains will drop out.’

‘Lie still, Georges-Jacques,’ Anne Madeleine said. ‘You gave that bull something to think about. He’ll run and hide when he sees you again.’

His mother said, ‘I wish I had a husband.’

NO ONE HAD LOOKED at his nose much before the incident, so no one could say whether a noble feature had been impaired. But the place scarred badly where the bull’s horn had ripped up his face. The line of damage ran down the side of his cheek, and intruded a purple-brown spur into his upper lip.

The next year he caught smallpox. So did the girls; as it happened, none of them died. His mother did not think that the marks detracted from him. If you are going to be ugly it is as well to be whole-hearted about it, put some effort in. Georges turned heads.

When he was ten years old his mother married again. He was Jean Recordain, a merchant from the town; he was a widower, with one (quiet) boy to bring up. He had a few little eccentricities, but she thought they would do very well together. Georges went to school, a small local affair. He soon found that he could learn anything without the least trouble, so he did not allow school to impinge on his life. One day he was walked on by a herd of pigs. Cuts and bruises resulted, another scar or two hidden by his thick wiry hair.

‘That’s positively the last time I’ll be trampled on by any animal,’ he said. ‘Four-legged or two-legged.’

‘Please God it may be,’ his stepfather said piously.

A YEAR PASSED. One day he collapsed suddenly, with a burning fever, chattering teeth. He coughed sputum stained with blood, and a scraping, crackling noise came from his chest, quite audible to anyone in the room. ‘Lungs possibly not too good,’ the leech said. ‘All those ribs driven into them at frequent intervals. Sorry, my dear. Better fetch the priest.’

The priest came. He gave him the last rites. But the boy failed to die that night. Three days later he still clung to a comatose half-life. His sister Marie-Cécile organized a cycle of prayers; she took the hardest shift, two o’clock in the morning till dawn. The parlour filled up with relations, sitting around trying to say the right thing. There were yawning silences, broken by the desperate sound of everyone speaking at once. News of each breath was relayed from room to room.

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.