Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine"

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Gail Honeyman 2017

Cover design: Holly MacDonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Jacket photography © Plain Picture / Hanka Steidle

Extract of The Lonely City (2016) by Olivia Laing reproduced by permission from Canongate Books Ltd

Gail Honeyman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008172114

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008172138

Version: 2020-01-23

Praise for Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine

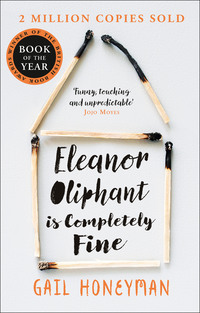

‘Eleanor Oliphant is a truly original literary creation: funny, touching, and unpredictable. Her journey out of dark shadows is expertly woven and absolutely gripping’

Jojo Moyes, Me Before You

‘A highly readable but beautifully written story that’s as perceptive and wise as it is funny and endearing … warm, funny and thought-provoking’

Observer

‘At times dark and poignant, at others bright and blissfully funny … a story about loneliness and friendship, and a careful study of abuse, buried grief and resilience. A debut to treasure’

Gavin Extence, The Universe Versus Alex Woods

‘Gail Honeyman’s Eleanor Oliphant is a woman scarred by profound loneliness, and the shadow of a harrowing childhood she can’t even bear to remember. Deft, compassionate and deeply moving – Honeyman’s debut will have you rooting for Eleanor with every turning page’

Paula McClain, The Paris Wife

‘So powerful – I completely loved Eleanor Oliphant’

Fiona Barton, The Widow

‘An absolute joy, laugh-out-loud funny but deeply moving’

Daily Express

‘One of the most eagerly anticipated debuts of 2017 … heartbreaking’

Bryony Gordon, Mad Girl

‘Unusual and arresting’

Rosie Thomas, The Kashmir Shawl

‘Warm, quirky and fun with a real poignancy underneath.’

Julie Cohen, Falling

‘Dark, funny and brave. I loved being with Eleanor as she found her voice’

Ali Land, Good Me Bad Me

‘A roaring success. Readers will fall in love with this quirky, yet loveable character and celebrate as life turns out a little differently than she anticipated’

Instyle.co.uk

Dedication

For my family

Epigraph

‘… loneliness is hallmarked by an intense desire to bring the experience to a close; something which cannot be achieved by sheer willpower or by simply getting out more, but only by developing intimate connections. This is far easier said than done, especially for people whose loneliness arises from a state of loss or exile or prejudice, who have reason to fear or mistrust as well as long for the society of others.

‘… the lonelier a person gets, the less adept they become at navigating social currents. Loneliness grows around them, like mould or fur, a prophylactic that inhibits contact, no matter how badly contact is desired. Loneliness is accretive, extending and perpetuating itself. Once it becomes impacted, it is by no means easy to dislodge.’

Olivia Laing, The Lonely City

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine

Dedication

Epigraph

Good Days

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Bad Days

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Better Days

Chapter 41

Bonus Content

Acknowledgements

Transcript

About the Author

About the Publisher

1

WHEN PEOPLE ASK ME what I do – taxi drivers, dental hygienists – I tell them I work in an office. In almost nine years, no one’s ever asked what kind of office, or what sort of job I do there. I can’t decide whether that’s because I fit perfectly with their idea of what an office worker looks like, or whether people hear the phrase work in an office and automatically fill in the blanks themselves – lady doing photocopying, man tapping at a keyboard. I’m not complaining. I’m delighted that I don’t have to get into the fascinating intricacies of accounts receivable with them. When I first started working here, whenever anyone asked, I used to tell them that I worked for a graphic design company, but then they assumed I was a creative type. It became a bit boring to see their faces blank over when I explained that it was back office stuff, that I didn’t get to use the fine-tipped pens and the fancy software.

I’m nearly thirty years old now and I’ve been working here since I was twenty-one. Bob, the owner, took me on not long after the office opened. I suppose he felt sorry for me. I had a degree in Classics and no work experience to speak of, and I turned up for the interview with a black eye, a couple of missing teeth and a broken arm. Maybe he sensed, back then, that I would never aspire to anything more than a poorly paid office job, that I would be content to stay with the company and save him the bother of ever having to recruit a replacement. Perhaps he could also tell that I’d never need to take time off to go on honeymoon, or request maternity leave. I don’t know.

It’s definitely a two-tier system in the office; the creatives are the film stars, the rest of us merely supporting artists. You can tell by looking at us which category we fall into. To be fair, part of that is salary-related. The back office staff get paid a pittance, and so we can’t afford much in the way of sharp haircuts and nerdy glasses. Clothes, music, gadgets – although the designers are desperate to be seen as freethinkers with unique ideas, they all adhere to a strict uniform. Graphic design is of no interest to me. I’m a finance clerk. I could be issuing invoices for anything, really: armaments, Rohypnol, coconuts.

From Monday to Friday, I come in at 8.30. I take an hour for lunch. I used to bring in my own sandwiches, but the food at home always went off before I could use it up, so now I get something from the high street. I always finish with a trip to Marks and Spencer on a Friday, which rounds off the week nicely. I sit in the staffroom with my sandwich and I read the newspaper from cover to cover, and then I do the crosswords. I take the Daily Telegraph, not because I like it particularly, but because it has the best cryptic crossword. I don’t talk to anyone – by the time I’ve bought my Meal Deal, read the paper and finished both crosswords, the hour is almost up. I go back to my desk and work till 5.30. The bus home takes half an hour.

I make supper and eat it while I listen to The Archers. I usually have pasta with pesto and salad – one pan and one plate. My childhood was full of culinary contradiction, and I’ve dined on both hand-dived scallops and boil-in-the-bag cod over the years. After much reflection on the political and sociological aspects of the table, I have realized that I am completely uninterested in food. My preference is for fodder that is cheap, quick and simple to procure and prepare, whilst providing the requisite nutrients to enable a person to stay alive.

After I’ve washed up, I read a book, or sometimes I watch television if there’s a programme the Telegraph has recommended that day. I usually (well, always) talk to Mummy on a Wednesday evening for fifteen minutes or so. I go to bed around ten, read for half an hour and then put the light out. I don’t have trouble sleeping, as a rule.

On Fridays, I don’t get the bus straight after work but instead I go to the Tesco Metro around the corner from the office and buy a margherita pizza, some Chianti and two big bottles of Glen’s vodka. When I get home, I eat the pizza and drink the wine. I have some vodka afterwards. I don’t need much on a Friday, just a few big swigs. I usually wake up on the sofa around 3 a.m., and I stumble off to bed. I drink the rest of the vodka over the weekend, spread it throughout both days so that I’m neither drunk nor sober. Monday takes a long time to come around.

My phone doesn’t ring often – it makes me jump when it does – and it’s usually people asking if I’ve been mis-sold Payment Protection Insurance. I whisper I know where you live to them, and hang up the phone very, very gently. No one’s been in my flat this year apart from service professionals; I’ve not voluntarily invited another human being across the threshold, except to read the meter. You’d think that would be impossible, wouldn’t you? It’s true, though. I do exist, don’t I? It often feels as if I’m not here, that I’m a figment of my own imagination. There are days when I feel so lightly connected to the earth that the threads that tether me to the planet are gossamer thin, spun sugar. A strong gust of wind could dislodge me completely, and I’d lift off and blow away, like one of those seeds in a dandelion clock.

The threads tighten slightly from Monday to Friday. People phone the office to discuss credit lines, send me emails about contracts and estimates. The employees I share an office with – Janey, Loretta, Bernadette and Billy – would notice if I didn’t turn up. After a few days (I’ve often wondered how many) they would worry that I hadn’t phoned in sick – so unlike me – and they’d dig out my address from the personnel files. I suppose they’d call the police in the end, wouldn’t they? Would the officers break down the front door? Find me, covering their faces, gagging at the smell? That would give them something to talk about in the office. They hate me, but they don’t actually wish me dead. I don’t think so, anyway.

I went to the doctor yesterday. It feels like aeons ago. I got the young doctor this time, the pale chap with the red hair, which I was pleased about. The younger they are, the more recent their training, and that can only be a good thing. I hate it when I get old Dr Wilson; she’s about sixty, and I can’t imagine she knows much about the latest drugs and medical breakthroughs. She can barely work the computer.

The doctor was doing that thing where they talk to you but don’t look at you, reading my notes on the screen, hitting the return key with increasing ferocity as he scrolled down.

‘What can I do for you this time, Miss Oliphant?’

‘It’s back pain, Doctor,’ I told him. ‘I’ve been in agony.’ He still didn’t look at me.

‘How long have you been experiencing this?’ he said.

‘A couple of weeks,’ I told him.

He nodded.

‘I think I know what’s causing it,’ I said, ‘but I wanted to get your opinion.’

He stopped reading, finally looked across at me.

‘What is it that you think is causing your back pain, Miss Oliphant?’

‘I think it’s my breasts, Doctor,’ I told him.

‘Your breasts?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘You see, I’ve weighed them, and they’re almost half a stone – combined weight, that is, not each!’ I laughed. He stared at me, not laughing. ‘That’s a lot of weight to carry around, isn’t it?’ I asked him. ‘I mean, if I were to strap half a stone of additional flesh to your chest and force you to walk around all day like that, your back would hurt too, wouldn’t it?’

He stared at me, then cleared his throat.

‘How … how did you …?’

‘Kitchen scales,’ I said, nodding. ‘I just sort of … placed one on top. I didn’t weigh them both, I made the assumption that they’d be roughly the same weight. Not entirely scientific I know, but—’

‘I’ll write you a prescription for some more painkillers, Miss Oliphant,’ he said, talking over me and typing.

‘Strong ones this time, please,’ I said firmly, ‘and plenty of them.’ They’d tried to fob me off before with tiny doses of aspirin. I needed highly efficient medication to add to my stockpile.

‘Could I also have a repeat prescription for my eczema medication, please? It does seem to become exacerbated at times of stress or excitement.’

He did not grace this polite request with a response but simply nodded. Neither of us spoke as the printer spat out the paperwork, which he handed to me. He stared at the screen again and started typing. There was an awkward silence. His social skills were woefully inadequate, especially for a people-facing job like his.

‘Goodbye then, Doctor,’ I said. ‘Thank you so very much for your time.’ My tone went completely over his head. He was still, apparently, engrossed in his notes. That’s the only downside to the younger ones; they have a terrible bedside manner.

That was yesterday morning, in a different life. Today, after, the bus was making good progress as I headed for the office. It was raining, and everyone else looked miserable, huddled into their overcoats, sour morning breath steaming up the windows. Life sparkled towards me through the drops of rain on the glass, shimmered fragrantly above the fug of wet clothes and damp feet.

I have always taken great pride in managing my life alone. I’m a sole survivor – I’m Eleanor Oliphant. I don’t need anyone else – there’s no big hole in my life, no missing part of my own particular puzzle. I am a self-contained entity. That’s what I’ve always told myself, at any rate. But last night, I’d found the love of my life. When I saw him walk on stage, I just knew. He was wearing a very stylish hat, but that wasn’t what drew me in. No – I’m not that shallow. He was wearing a three-piece suit, with the bottom button of his waistcoat unfastened. A true gentleman leaves the bottom button unfastened, Mummy always said – it was one of the signs to look out for, signifying as it did a sophisticate, an elegant man of the appropriate class and social standing. His handsome face, his voice … here, at long last, was a man who could be described with some degree of certainty as ‘husband material’.

Mummy was going to be thrilled.

2

AT THE OFFICE, THERE was that palpable sense of Friday joy, everyone colluding with the lie that somehow the weekend would be amazing and that, next week, work would be different, better. They never learn. For me, though, things had changed. I had not slept well, but despite that, I was feeling good, better, best. People say that when you come across ‘the one’, you just know. Everything about this was true, even the fact that fate had thrown him into my path on a Thursday night, and so now the weekend stretched ahead invitingly, full of time and promise.

One of the designers was finishing up today – as usual, we’d be marking the occasion with cheap wine and expensive beer, crisps dumped in cereal bowls. With any luck, it would start early, so I could show my face and still leave on time. I simply had to get to the shops before they closed. I pushed open the door, the chill of the air-con making me shudder, even though I was wearing my jerkin. Billy was holding court. He had his back to me, and the others were too engrossed to notice me slip in.

‘She’s mental,’ he said.

‘Well, we know she’s mental,’ Janey said, ‘that was never in doubt. The question is, what did she do this time?’

Billy snorted. ‘You know she won those tickets and asked me to go to that stupid gig with her?’

Janey smiled. ‘Bob’s annual raffle of crap client freebies. First prize, two free tickets. Second prize, four free tickets …’

Billy sighed. ‘Exactly. Total embarrassment of a Thursday night out – a charity gig in a pub, starring the marketing team of our biggest client, plus various cringeworthy party pieces from all their friends and family? And, to make it worse, with her?’

Everyone laughed. I couldn’t disagree with his assessment; it was hardly a Gatsbyesque night of glamour and excess.

‘There was one band in the first half – Johnnie something and the Pilgrim Pioneers – who weren’t actually that bad,’ he said. ‘They mostly played their own stuff, some covers too, classic oldies.’

‘I know him – Johnnie Lomond!’ Bernadette said. ‘He was in the same year as my big brother. Came to our house for a party one night when Mum and Dad were in Tenerife, him and some of my brother’s other mates from Sixth Year. Ended up blocking the bathroom sink, if I remember right …’

I turned away, not wishing to hear about his youthful indiscretions.

‘Anyway,’ said Billy – he did not like being interrupted, I’d noticed – ‘she absolutely hated that band. She just sat there frozen; didn’t move, didn’t clap, anything. Soon as they finished, she said she needed to go home. So she didn’t even make it to the interval, and I had to sit there on my own for the rest of the gig, like, literally, Billy No-Mates.’

‘That’s a shame, Billy; I know you were wanting to take her for a drink afterwards, maybe go dancing,’ Loretta said, nudging him.

‘You’re so funny, Loretta. No, she was off like a shot. She’d have been tucked up in bed with a cup of cocoa and a copy of Take a Break before the band had even finished their set.’

‘Oh,’ said Janey, ‘I don’t see her as a Take a Break reader, somehow. It’d be something much weirder, much more random. Angling Times? What Caravan?’

‘Horse and Hound,’ said Billy firmly, ‘and she’s got a subscription.’ They all sniggered.

I laughed myself at that one, actually.

I hadn’t been expecting it to happen last night, not at all. It hit me all the harder because of that. I’m someone who likes to plan things properly, prepare in advance and be organized. This came out of nowhere; it felt like a slap in the face, a punch to the gut, a burning.

I’d asked Billy to come to the concert with me, mainly because he was the youngest person in the office; for that reason, I assumed he’d enjoy the music. I heard the others teasing him about it when they thought I was out at lunch. I knew nothing about the concert, hadn’t heard of any of the bands. I was going out of a sense of duty; I’d won the tickets in the charity raffle, and I knew people would ask about it in the office.

I had been drinking sour white wine, warm and tainted by the plastic glasses the pub made us drink from. What savages they must think us! Billy had insisted on buying it, to thank me for inviting him. There was no question of it being a date. The very notion was ridiculous.

The lights went down. Billy hadn’t wanted to watch the support acts, but I was adamant. You never know if you’ll be bearing witness as a new star emerges, never know who’s going to walk onto the stage and set it alight. And then he did. I stared at him. He was light and heat. He blazed. Everything he came into contact with would be changed. I sat forward on my seat, edged closer. At last. I’d found him.

Now that fate had unfurled my future, I simply had to find out more about him; the singer, the answer. Before I tackled the horror that was the month-end accounts, I thought I’d have a quick look at a few sites – Argos, John Lewis – to see how much a computer would cost. I suppose I could have come into the office during the weekend and used one, but there was a high risk that someone else would be around and ask what I was doing. It’s not like I’d be breaking any rules, but it’s no one else’s business, and I wouldn’t want to have to explain to Bob how I’d been working weekends and yet still hadn’t managed to make a dent in the huge pile of invoices waiting to be processed. Plus, I could do other things at home at the same time, like cook a trial menu for our first dinner together. Mummy told me, years ago, that men go absolutely crazy for sausage rolls. The way to a man’s heart, she said, is a homemade sausage roll, hot flaky pastry, good quality meat. I haven’t cooked anything except pasta for years. I’ve never made a sausage roll. I don’t suppose it’s terribly difficult, though. It’s only pastry and mechanically recovered meat.

I switched on the machine and entered my password, but the whole screen froze. I turned the computer off and on again, and this time it didn’t even get as far as the password prompt. Annoying. I went to see Loretta, the office manager. She has overinflated ideas of her own administrative abilities, and in her spare time makes hideous jewellery, which she then sells to idiots. I told her my computer wasn’t working, and that I hadn’t been able to get hold of Danny in IT.

‘Danny left, Eleanor,’ she said, not looking up from her screen. ‘There’s a new guy now. Raymond Gibbons? He started last month?’ She said this as though I should have known. Still not looking up, she wrote his full name and telephone extension on a Post-it note and handed it to me.

‘Thank you so much, you’ve been extremely helpful as usual, Loretta,’ I said. It went over her head, of course.

I phoned the number but got his voicemail: ‘Hi, Raymond here, but also not here. Like Schrödinger’s cat. Leave a message after the beep. Cheers.’

I shook my head in disgust, and spoke slowly and clearly into the machine.

‘Good morning, Mister Gibbons. My name is Miss Oliphant and I am the finance clerk. My computer has stopped working and I would be most grateful if you could see your way to repairing it today. Should you require any further details, you may reach me on extension five-three-five. Thank you most kindly.’

I hoped that my clear, concise message might serve as an exemplar for him. I waited for ten minutes, tidying my desk, but he did not return my call. After two hours of paper filing and in the absence of any communication from Mr Gibbons, I decided to take a very early lunch break. It had crossed my mind that I ought to ready myself physically for a potential meeting with the musician by making a few improvements. Should I make myself over from the inside out, or work from the outside in? I compiled a list in my head of all of the appearance-related work which would need to be undertaken: hair (head and body), nails (toe and finger), eyebrows, cellulite, teeth, scars … all of these things needed to be updated, enhanced, improved. Eventually, I decided to start from the outside and work my way in – that’s what often happens in nature, after all. The shedding of skin, rebirth. Animals, birds and insects can provide such useful insights. If I’m ever unsure as to the correct course of action, I’ll think, ‘What would a ferret do?’ or, ‘How would a salamander respond to this situation?’ Invariably, I find the right answer.

I walked past Julie’s Beauty Basket every day on my way to work. As luck would have it, they had a cancellation. It would take around twenty minutes, Kayla would be my therapist, and it would cost forty-five pounds. Forty-five! Still, I reminded myself as Kayla led me towards a room downstairs, he was worth it. Kayla, like the other employees, was wearing a white outfit resembling surgical scrubs and white clogs. I approved of this pseudo-medical apparel. We went into an uncomfortably small room, barely large enough to accommodate the bed, chair and side table.

‘Now then,’ she said, ‘what you need to do is pop off your …’ she paused and looked at my lower half ‘… erm, trousers, and your underwear, then pop up onto the couch. You can be naked from the waist down or, if you prefer, you can pop these on.’ She placed a small packet on the bed. ‘Cover yourself with the towel and I’ll pop back in to see you in a couple of minutes. OK?’

I nodded. I hadn’t anticipated quite so much popping.

Once the door had closed behind her, I removed my shoes and stepped out of my trousers. Should I keep my socks on? I thought, on balance, that I probably should. I pulled down my underpants and wondered what to do with them. It didn’t seem right to drape them over the chair, in full view, as I’d done with my trousers, so I folded them up carefully and put them into my shopper. Feeling rather exposed, I picked up the little packet that she’d left on the bed and opened it. I shook out the contents and held them up: a very small pair of black underpants, in a style which I recognized as ‘Tanga’ in Marks and Spencer’s nomenclature, and made from the same papery fabric as teabags. I stepped into them and pulled them up. They were far too small, and my flesh bulged out from the front, sides and back.

The bed was very high and I found a plastic step underneath that I used to help me ascend. I lay down; it was lined with towels and topped with the same scratchy blue paper that you find on the doctor’s couch. Another black towel was folded at my feet, and I pulled it up to my waist to cover myself. The black towels worried me. What sort of dirty staining was the colour choice designed to hide? I stared at the ceiling and counted the spotlights, then looked from side to side. Despite the dim lighting, I could see scuff marks on the pale walls. Kayla knocked and entered, all breezy cheerfulness.

‘Now then,’ she said, ‘what are we doing today?’

‘As I said, a bikini wax, please.’

She laughed. ‘Yes, sorry, I meant what kind of wax would you like?’

I thought about this. ‘Just the usual kind … the candle kind?’ I said.

‘What shape?’ she said tersely, then noticed my expression. ‘So,’ she said patiently, counting them off on her fingers, ‘you’ve got your French, your Brazilian or your Hollywood.’

I pondered. I ran the words through my mind again, over and over, the same technique I used for solving crossword anagrams, waiting for the letters to settle into a pattern. French, Brazilian, Hollywood … French, Brazilian, Hollywood …

‘Hollywood,’ I said, finally. ‘Holly would, and so would Eleanor.’

She ignored my wordplay, and lifted up the towel. ‘Oh …’ she said. ‘Okaaaay …’ She went over to the table and opened a drawer, took something out. ‘It’s going to be an extra two pounds for the clipper guard,’ she said sternly, pulling on a pair of disposable gloves.

The clippers buzzbuzzbuzzed and I stared at the ceiling. This didn’t hurt at all! When she’d finished, she used a big, fat brush to sweep the shaved hair onto the floor. I felt panic start to rise within me. I hadn’t looked at the floor when I came in. What if she’d done this with the other clients – were their pubic hairs now adhering to the soles of my polka dot socks? I started to feel slightly sick at the thought.

‘That’s better,’ she said. ‘Now, I’ll be as quick as I can. Don’t use perfumed lotions in the area for at least twelve hours after this, OK?’ She stirred the pot of wax that was heating on the side table.

‘Oh, don’t worry, I’m not much of a one for unguents, Kayla,’ I said. She goggled at me. I’d have thought that staff in the beauty business would have better-developed people skills. She was almost as bad as my colleagues back at the office.

She pushed the paper pants to one side and asked me to pull the skin taut. Then she painted a stripe of warm wax onto my pubis with a wooden spatula, and pressed a strip of fabric onto it. Taking hold of the end, she ripped it off in one rapid flourish of clean, bright pain.

‘Morituri te salutant,’ I whispered, tears pricking my eyes. This is what I say in such situations, and it always cheers me up no end. I started to sit up, but she gently pushed me back down.

‘Oh, there’s a good bit more to go, I’m afraid,’ she said, sounding quite cheerful.

Pain is easy; pain is something with which I am familiar. I went into the little white room inside my head, the one that’s the colour of clouds. It smells of clean cotton and baby rabbits. The air inside the room is the palest sugar almond pink, and the loveliest music plays. Today, it was ‘Top of the World’ by The Carpenters. That beautiful voice … she sounds so blissful, so full of love. Lovely, lucky Karen Carpenter.

Kayla continued to dip and rip. She asked me to bend my knees out to the sides and place my heels together. Like frog’s legs, I said, but she ignored me, intent on her work. She ripped out the hair from right underneath. I hadn’t even considered that such a thing would be possible. When she’d finished, she asked me to lie normally again and then pulled down the paper pants. She smeared hot wax onto the remaining hair and ripped it all off triumphantly.