Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Something Wholesale"

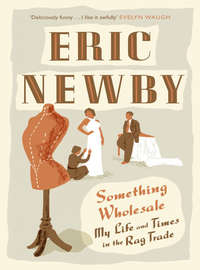

ERIC NEWBY

Something Wholesale

My Life and Times in the Rag Trade

Dedication

To My Father

Splendid in Defeat

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

1. A Short History of the Second World War

2. An Afternoon at Throttle and Fumble

3. Life with Father and Mother

4. Old Mr Newby

5. Back to Normal

6. In the Mantles

7. All Bruised

8. Sir No More

9. George’s Boy

10. A Day in the Showroom

11. Export or Die

12. Something Wholesale

13. Hi! Taxi!

14. A Nice Bit of Crêpe

15. North with Mr Wilkins

16. Caledonia Stern and Wild

17. On the Beach

18. A Night at Queen Charlotte’s

19. A Man Called Christian

20. Birth of an Explorer

21. Lunch with Mr Eyre

22. The End of Lane and Newby

23. Model Buyer

Epilogue – The Last Time I Saw Paris

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface

The hero of this book, if it has one, is the man who, during the years it describes, was head of the dressmaking firm of Lane and Newby – in other words my father. But this was my father in old age. We were separated by a great gulf of years, and when I was old enough to appreciate him the world which he knew and of which he was a part had passed away.

What do I know of my father as a young man? Practically nothing. His father came from the East Riding of Yorkshire and he acquired a stepmother at an early age. I know that with her his life was not very happy. It was one of the few things that when he spoke of it moved him to tears.

I look at photographs of him in our family albums taken when he was twenty or so – great group photographs of men and girls upriver, perhaps, after an outing or a regatta – and wonder what he and his companions were really like. He was very handsome, this is obvious – with a fine, well-tended moustache – and he was elegant, either in a negligent manner with a silk handkerchief knotted round his neck and a panama hat with the brim turned up in the front or else more formally in a dark suit with a watch chain and a straw hat with a black band.

The girls are dressed to the nines with fichus of lace and hats like great presentation baskets of fruit from Fortnums.

They must be upriver. In the background of the particular picture of which I am thinking there is a white clap-boarded house. It is probably a club-house or it might be a mill and beyond it the woods are thick and green, like the Quarry Woods at Marlow, only the house is not at Marlow.

Where is it? I wish I knew. There is no one left to ask. Perhaps, somewhere, one or two of those young men and women are left alive, but they would be very old now.

Some of the girls must have been beautiful but one must make an effort of will to believe it. Their clothes makes them seem older than they really were. And the way in which the photographer took his pictures endows them with too much chin, or else no chin at all. They look absurdly young or else like maiden aunts. The effort of keeping still for the photographer on that warm summer’s day and looking into the sun was too much for them, particularly for the men. Some of them are squinting, some are out of focus, some have an air of being slightly insane. It is gratifying to see that in all these groups my father took the precaution of seating himself next to the most good-looking girl available. I would like to know how they spoke, these friends of my father; the idioms they used; the things that made them laugh; but I shall never know, more’s the pity and neither will my children.

There are more rural scenes. Photographs taken not by a professional but by one of my father’s companions when they were camping, in the doorway of a tent, early in the morning with the mist still rising from the meadows. They look dishevelled, as if none of them had slept well, perhaps there were horses in the field. One of them is smoking a meerschaum pipe with a Turk’s head carved on it. In the foreground there is a large black cooking pot, suspended from a metal tripod, simmering over a wood fire. All the cooking equipment is tremendously heavy. How did they get it there? They must have used a horse-drawn vehicle. It is a pity that there is no picture of it.

There is a series of photographs taken off the East Coast in a yacht with a hired man. ‘He was a real old salt,’ my father told me. In these pictures he and his friends are all wearing black and white striped trousers rolled up to the knees and stockinette caps. In the background of one of them there is a light-ship and close to it a barquentine, deep-loaded, running before the wind. Whoever took the photograph had difficulty with it because the horizon goes rapidly downhill! ‘There was a bit of a lop on,’ my father said, wistfully. He had always wanted to be a sailor. And when his father married again he tried to run away to sea but was brought back in a cab. Next in time are the photographs of my mother taken the year before I was born, looking gentle and rather sad, and another of my father looking severe and bristly reclining on a velvet cushion up in the bows of his skiff. I wonder how things went that day. Was she having sculling lessons at that time? Perhaps she wasn’t getting her hands away properly.

The next photographs are of my father partially domesticated, taken on the beach at Frinton. I am on the scene now, large and shiny in a large, shiny pram. I look like an advertisement for some health food. I think my father has just arrived from London on the afternoon train. He is dressed for London. Looking at the photograph now I almost convince myself that I remember the moment when it was taken. But who took it? I seem to remember a nurse with starched cuffs and dark rings under her eyes who used to have assignations with old men in the local cemetery when she was supposed to be giving me an airing, and was summarily fired for it. Perhaps she took the picture.

There are pictures on Sark. I am sitting on my father’s head as he wades through the bracken. It was an enchanting spot in the Twenties. There are a lot of photographs of the Twenties. My mother in a cloche hat at Deauville. Scenes at Branscombe in Devonshire of two sisters, both store buyers, Lolly and Polly, friends of my parents, identical in long jerseys and strings of beads, surrounded by a whole pack of Pekinese.

Lolly was the best suit buyer in London. She was extremely good-hearted but could be extremely autocratic. On one occasion a customer had a suit on approval and, thinking that she would not be detected, wore it at the Royal Military Meeting at Sandown Park, where she was seen by Lolly, who was mad about racing.

On the following Monday the customer returned to the store and complained that the suit which she was wearing had some imperfection in it and demanded a reduction in price.

‘If there’s something wrong with it,’ said Lolly, ‘then you shan’t bloody well have it.’

She made her take it off in a fitting-room. ‘Now bloody well go home without it!’ she said.

Eventually the customer had to buy another suit in order to leave the building, one that was even more expensive than the original, which Lolly promptly marked-down in price and appropriated to her own use, having wanted it for herself in the first place.

There is a whole gallery of memorable characters in these albums. Captain and Mrs Buckle – Mrs Buckle smoked a hundred cigarettes a day. ‘Gaspers’ she used to call them, and her voice was reduced to a hollow croak. Ivor – a young man who had an open Vauxhall with a boat-shaped body and used to drive to Devonshire in silk pyjamas after parties in London. He inherited a fortune when he was twenty-one, got through it in a year and became a bus driver. He used to wave to my mother when he drove the number nines over Hammersmith Bridge. And there is another buyer called Phyll – who lived in sin with someone called Uncle Fred, who wasn’t an uncle. At Christmas time Auntie Phyll’s flat resembled a robber’s cave with presents from manufacturers piled high in it. Those were days when a fashion buyer was expected to feather her nest (nobody else was going to do it for her) and many a buyer was able to retire to a riverside cottage on the proceeds of the toll she exacted from the manufacturers on every dress that went into her department. On one occasion a disgruntled manufacturer informed the management that Auntie Phyll was taking a percentage in this way but was nonplussed when he was told by the Managing Director that they didn’t care what bribes she received providing that the clothes she bought were as well chosen and as cheap as those of their competitors.

And there is a whole supporting cast of rural characters from the village where we had taken a cottage for the summer. Photographs of the innkeeper, who was having a violent affair with the barmaid under the nose of his wife; photographs of his wife and the barmaid, who looks very innocent in a velvet dress, and pictures of village children with whom I used to float paper boats down an open sewer; and the policeman’s son who taught me to say bloody. Once for a bet I drank the water from the sewer. The results were not what normal medical experience would lead one to expect. Instead of contracting dysentery I had a complete stoppage of the bowels that lasted for more than a week.

And there is the last photograph I have of my father. He is sitting with my mother in an umpire’s launch on the river at Hammersmith. It is the summer of the year he died. He has shrunk with the years, but with his white club cap he looks for all the world like a mischievous schoolboy.

CHAPTER ONE A Short History of the Second World War

One morning in August 1940 ‘A’ Company, Infantry Wing, was on parade outside the Old Buildings at the Royal Military College, Camberley. Company Sergeant-Major Clegg, a foxy looking Grenadier, was addressing us ‘… THERE WILL BE NO WEEKEND LEAF,’ he screamed with satisfaction. (There never had been.) ‘That means no women for Mr Pont, Mr Pont (there were two Mr Ponts – cousins). Take that smile off your face Mr Newby or you’ll be inside. Wiring and Demolition Practice at 1100 hours is cancelled for Number One Platoon. Instead there will be Bridging Practice. Bridging Equipment will be drawn at 1030 hours. CUMPNEE … CUMPNEEEE … SHAAH!’

‘Heaven,’ said the Ponts as we doubled smartly to our rooms to change for P.T. ‘There’s nothing more ghastly than all that wire.’

I, too, was glad that there was to be no Wiring and Demolition. Both took place in a damp, dark wood. Wiring was hell at any rate and Demolition for some mysterious reason was conducted by a civilian. It always seemed to me the last thing a civilian should have a hand in and I was not surprised when, later in the war, he disappeared in a puff of smoke, hoist by one of his own petards.

In June 1940, after six months of happy oblivion as a private soldier, I had been sent to Sandhurst to be converted into an officer.

Pressure of events had forced the Royal Military College to convert itself into an O.C.T.U., an Officer Cadet Training Unit, and the permanent staff still referred meaningfully in the presence of the new intakes to a golden age ‘when the gennulmen cadets were ’ere’.

‘’Ere’ we learned to drill in an impressive fashion and our ability to command was strengthened by the Adjutant, magnificent in breeches and riding boots from Maxwell, who had us stationed in pairs on the closely mown lawns that sloped gently to the lake. A quarter of a mile apart, he made us screech at one another, marching and countermarching imaginary battalions by the left, by the right and by the centre until our voices broke under the strain and whirred away into nothingness.

Less well we carried out a drill with enormous military bicycles as complex as the evolutions performed by Lippizanas at the Spanish Riding School. On these treadmills which each weighed between sixty and seventy pounds, we used to wobble off into the surrounding pine plantations, which we shared uneasily with working parties of lunatics from the asylum at Broadmoor, for T.E.W.T.s – Tactical Exercises Without Troops.

Whether moving backwards or forwards the T.E.W.T. world was a strange, isolated one in which the lunatics who used to wave to us as we laid down imaginary fields of fire against an imaginary enemy might have been equally at home. In it aircraft were rarely mentioned, tanks never. We were members of the Infantry Wing. There was an Armoured Wing for those who were interested in such things as tanks and armoured cars and the authorities had no intention of allowing the two departments to mingle. Gradually we succumbed to the pervasive unreality.

‘I want to bring home to you the meaning of this war,’ said a visiting General. ‘In four months those of you who are not R.T.U.’d – Returned to your Units – will be platoon commanders. In six months’ time most of you will be dead.’

And we believed him. Our numbers were already depleted by a mysterious outbreak of bed-wetting – an R.T.U.-able offence. In a military trance we imagined ourselves waving ashplants, charging machine-gun nests at the head of our men. The Carrara marble pillars, which supported the roof of the chapel in which we carried out our militant devotions, were scarcely sufficient to contain the names of all those other ‘gennulmen’ who, in the earlier war, had died in the mud at Passchendaele and among the wire on the forward slopes of the Hohenzollern Redoubt. They had sat where we were sitting and their names were set out in neat columns on the pillars like debit entries in some terrible ledger.

This dream of Death or Glory affected our leisure. Most of us had passed our formative years in the outer suburbs. Now, to make ourselves more acceptable to our employers we took up beagling (the College had the Eton Beagles for the duration); ordered shirts we couldn’t afford from expensive shirt-makers in Jermyn Street and drank Black Velvet in the Hotel. The snugger pubs were out of bounds for fear we might meet a barmaid who ‘did it’. No one but a maniac would have wanted to do it with the one at the Hotel.

The bridging equipment was housed in a low, sinister-looking shed near the lake on which we were to practise. This was not the ornamental lake in front of the Old Buildings on which, in peace time, playful cadets used to float chamber pots containing lighted candles – a practice now forbidden by the blackout regulations. It was an inferior lake, little more than a pond; from it rose a dank smell of rotting vegetation.

Inside the shed there were a number of small decked-in pontoons and strips of heavy teak grating which were intended to form the footway. Blocks and tackle hung in great swathes from the roof; presumably they were to hold the bridge steady in a swiftly flowing stream. Everything seemed unnecessarily heavy, as though it was part of the gear of a wooden ship-of-the-line.

There was every sign that the bridge had not been used for years – if at all. The custodian, a grumpy old pensioner rooted out of his cottage to open the door, confirmed this.

‘What yer think yer going to do with it, cross the Channel?’ he croaked.

The Staff Sergeant detailed to instruct us in the use of the bridge was uneasy. He had never seen anything like it before. It bore no resemblance to any kind of bridge that he had encountered.

‘It’s not an ISSUE BRIDGE,’ he kept repeating, plaintively. ‘Gennulmen, you must help me.’ We were deaf to him. The Army had seldom been kind to us; it was too late to call us gentlemen.

Finally, after rooting in the darkness he discovered a battered manual hanging on a nail behind the door. It confirmed our suspicions that the bridge had been constructed at the time of the Boer War. No surprise at the Royal Military College where a whole literature of the same period – text books filled with drawings of blockhouses with corrugated-iron roofs; men with droopy moustaches peering through loopholes; and armoured trains that I associated with the early life of Mr Winston Churchill – were piled high on the tops of cupboards in the lecture rooms and had obviously only recently fallen into disuse.

With the manual in his hand the Sergeant was once more on familiar ground – if one can use such an expression in connection with a bridge. His spirits rose still further when he discovered that there was a drill laid down for assembling the monstrous thing.

‘On the command “One” the even numbers of the front ranks will about turn, grasp the Caissons with both hands and advance into the water. On the command “Two” the odd numbers of the front rank will peg out the Guys, Retaining Caisson. On the command “Three” the even numbers of the rear rank will pick up the Sections, Decking’ … and so on.

On the command ‘One’ the Caisson Party, of which I was one, moved gingerly into the water, which was surprisingly warm. Some of the more frivolous cadets began to splash one another, but were rebuked by the Sergeant. After some twenty minutes all the Caissons were in position, secured by block and tackle.

‘Caisson Party, about turn, quick march!’ To the accompaniment of weird sucking noises we squelched ashore.

‘Decking Party, advance!’ The Decking Party staggered forward under its appalling load. Standing on the bank, with the water streaming from the bottoms of our trousers, we watched them go.

‘It all seems rather pointless when we’ve already walked across,’ someone said.

‘Quiet!’ said the Sergeant. ‘The next cadet who speaks goes on a charge.’ He was looking at his watch, apprehensively.

‘Decking Party and Caisson Party will retire and unpile arms,’ he went on. We had already performed the complicated operation of piling arms. It was one of the things we really knew how to do. ‘Now then, get a move on.’

We had just completed the unpiling when Sergeant-Major Clegg appeared on the far side of the lake, stiff as a ramrod, jerkily propelling one of our gigantic bicycles. Dismounted, standing half-hidden in the undergrowth, he looked more foxy than ever.

He addressed us and the world in that high-pitched sustained scream that even now, when I recall it at dead of night twenty years later, makes me come to attention even when lying in my bed.

‘SAAAAN ALUN!’

‘SAAAAH!’

‘DOZEEEE … DOZEEEE … GET THOSE DOZY, IDUL GENNULMEN OVER THE BRIDGE … AT … THER … DUBBOOOOL!’

‘SAAAAH!’ shrieked Sergeant Allen and wheeled upon us with a face bereft of all humanity. ‘PLATOOOON, PLATOOOON WILL CROSS THE BRIDGE AT THER DUBOOL – DUBOOOOL!’

Armed to the teeth, bowed down by gas masks, capes antigas, token anti-tank rifles and 2” mortars made of wood (all the real ones had been taken away from us after Dunkirk), we thundered down the bank and on to the bridge.

The weight of thirty men was too much for it; there was a noise like a succession of pistol shots as the Guys, Retaining Caisson parted, the central span of the bridge surged away and the whole body of us crashed into the water. It was like the end of the Gadarene Swine, the Tay Bridge Disaster and the Crossing of the Beresina reproduced in miniature.

As we came to the surface, ornamented with weed and surrounded by the token wooden weapons which, surprisingly, in spite of their weight, floated, we began to laugh hysterically and what had begun as a military operation ended as a water frolic. The caissons became rafts on which were spread-eagled the waterlogged figures of what had until recently been officer cadets, who now resembled nothing more than a band of lascivious Tritons. People were ducking one another; the Ponts were floating calmly, contemplating the sky as if offshore at noon at Eden Roc …

Gradually the laughter ceased and a terrible silence descended on us. A tall ascetic figure was looking down on us with a mixture of incredulity and disgust from an ornamental bridge in the rustic taste. The Sergeant was saluting furiously; Sergeant-Major Clegg, foxy to the last, had slipped away into the undergrowth – only his bicycle, propped against a tree, showed that he had ever been there. The face on the bridge was a very well-known face.

Without a word General de Gaulle turned on his heel and went off, followed by a train of officers of high rank. His visit had been unannounced at his special request so that he could see us working under natural conditions. What he must have thought is unimaginable. France had just fallen. It must have confirmed his worst suspicions of the British Army. Perhaps the intransigence that was later to become a characteristic was born there on that bright morning beside a steamy little lake in Surrey.

For Sergeant Allen the morning’s work had a more immediate significance. His career seemed blasted.

‘You’ve gone and done me in,’ he said sadly, as we fell in to squelch back to the Old Buildings.

Four years, seven months and twenty-five days after that first abortive amphibious operation amongst the Camberley pines I stood on the dockside at Tilbury, the last of the last boatload of returning prisoners from Oflag 79.

I was much changed since that far-off day when Company Sergeant-Major Clegg had told me to take that smile off my face. Then, at least, I had been a soldier in embryo. Now, wearing a suit of battle dress that had been made for a giant, sprinkled liberally with delousing powder, which the authorities at Brussels had thought necessary before allowing me out to eat an ersatz gooseberry tart on Boulevard Anspach, I resembled nothing human, civil or military.

En masse, my companions and I were not objects of compassion. Ten days of liberty during which we had roamed the countryside of Saxony, searching for food that the local farmers had been too terrified to withhold from us, had so inflated our faces that they resembled grotesque balloons at a carnival, in startling contrast with our emaciated bodies, which were concealed by our uniforms.

Unlike the returned prisoner of popular imagination we were heavily laden: with kitbags stuffed with coats and great rubber riding mackintoshes bought at officers’ shops along the route, and with long woollen underpants that had been pressed upon us by helping organisations. In addition I was encumbered with a number of scientific instruments which I had looted from a German experimental station, under the impression that they would make my fortune, and, heaviest of all to bear, an anxiety neurosis brought on by my failure to complete, before liberation, a petit-point fire screen, one of thousands sent out by the Red Cross with the express purpose of allaying anxiety neurosis. I still have the instruments. No one has ever been able to tell me what they are intended for. I burned the fire screen and felt better for having done so.

It began to rain heavily. ‘Officers this way,’ said a sergeant from the disembarkation staff and we trailed after him under the arc lights, across greasy railway tracks on which tank engines hissed with steam up, to a long, low, wooden hut. Inside the other ranks were already eating bacon and eggs and drinking tea which was being served to them by cheerful, common ATS.

We were given tea by members of a more fashionable volunteer organisation whose roots were deep in S.W.7. They seemed more interested in the effect that they were producing on a number of men, who had not seen an English woman for anything up to five years, than in producing the victuals for which we still craved.

‘Do you know Jamie Stuart Ogilvie-Keir-Gordon in the Scots Guards? I think he was with you.’

‘No, I’m afraid not.’

‘Or Binkie Martyn-Sikes?’

‘No!’

‘How very odd that you shouldn’t have known him. He’s my second cousin.’

‘Do you think it would be possible for me to have something to eat?’

‘Oh, how stupid of me. It’s been so interesting talking to you I quite forgot.’

Whilst we were eating a Colonel entered. He was large, with a face as red as the tabs on his lapels.

‘Carry on, gentlemen,’ he said, genially. No one had in fact stopped. His costume was an unconvincing parody of a panoply which I now associated with a long-dead past. Neither breeches nor boots were as those worn by the terrifying but beautiful Eddie, our Adjutant at Sandhurst. Particularly the boots; they were downat-heel as though they had been worn over-much on urban pavements.

He sat himself down on the edge of one of the tables and tapped his awful boots with a little swagger cane.

‘Before you chaps move on from here,’ he said with a bonhomie which we found extremely distasteful, ‘there is just one thing I would like to say to you.

‘We realise here that things have been pretty rough for you on the other side. The Hun’s finished, now it’s our turn. I expect you saw some pretty rotten things – atrocities. I happen to be the Commandant of a P.O.W. Camp at—(he named a place somewhere remote in East Anglia). I’m also,’ he added, surprisingly, ‘a Member of Parliament. If you’ve witnessed any kind of atrocity in the last few years I would like you to report it to me, now. I promise you that whatever you tell me here will be brought home to the men in my camp. They’ll sweat it out.’

It had been a long day. I thought of the journey we had made through Belgium. There had been a shortage of rolling stock and we had entrained in carriages intended for the transportation of German prisoners. The windows were festooned with barbed wire. At the halts, which were numerous, small boys had thrown stones at us under the impression that we were members of the opposition. Who was to blame them? I thought of Germany – how I loathed pine trees and Alsatian dogs. I thought of the camp near Munich: the S.S. stripping Yugoslav men and women, kicking them round the compound in the snow and later singing harmoniously together in their huts, full of gemütlichkeit. I had seen a lot of things and this was too much.

Finally, an officer, who had been captured with the Rifle Brigade at Calais in 1940, got to his feet.

‘Colonel,’ he said, ‘I have two observations to make. The first is that you yourself are, without doubt, the biggest atrocity I have seen in the last five years. Secondly, the sooner there is a by-election in your constituency the better.

‘And in case,’ he went on, ‘you are now thinking of having me placed under arrest I will tell you that I have not yet been medically examined and I am probably quite insane – and that, Colonel, goes for everyone else in this room.’

There was a long, long train journey from Tilbury to Sussex without changing – a tour-de-force only possible in time of total war; the train stopping in the small hours of the morning at a disused platform deep in the bowels of Holborn viaduct.

‘Hasn’t been used since 1918,’ said the guard. He stood on the platform ankle deep in black soot, the accumulation of twenty-seven years, whilst those of us who lived in London argued whether or not to abandon the train and take taxis.

‘Can’t get a taxi in London after midnight – Yanks,’ said a gloomy looking Major with a handlebar moustache and little tufts of ginger hair growing out of his cheeks. ‘Had a letter from m’brother.’ At dawn the train crept into Barnes Station. I lived at Hammersmith Bridge, five minutes away by bus. It seemed ridiculous not to get out. I started assembling my extraordinary luggage. ‘Chap told me at Tilbury,’ the hairy Major said, ‘that they’re giving out special food and clothing coupons at Repatriation Centres.’

The train moved forward with a shattering jerk. Once more the house where I was born receded into the distance.

The Repatriation Centre was two Nissen huts in the middle of a wood somewhere in Sussex. It was staffed entirely by escaped prisoners of war, most of whom we already knew. In one hour dead they had us medically examined, documented and back at the station.

‘You get two months’ leave. Personally I don’t think that anyone will ever want to see you again,’ said the C.O. He had been in the same squad with me at Sandhurst. ‘The thing is,’ he said, slipping effortlessly back into the idiom, ‘you look so very, very idul.’

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.