Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Antkind: A Novel"

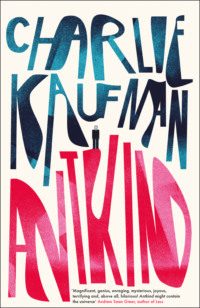

ANTKIND

A Novel

Charlie Kaufman

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020

Copyright © Charlie Kaufman, 2020

Cover design by Jack Smyth

Charlie Kaufman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This story collection is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008319533

Ebook Edition © July 2020 ISBN: 9780008319496

Version: 2020-06-09

Epigraph

It is so American, fire. So like us.

Its desolation. And its eventual, brief triumph.

—LARRY LEVIS, “My Story in a Late Style of Fire”

Smoke gets in your eyes

Smoke gets in your eyes

Smoke gets in your eyes

Smoke gets in your eyes

—“Smoke Gets in Your Eyes”

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Chapter 84

Chapter 85

Chapter 86

Chapter 87

Chapter 88

Chapter 89

Chapter 90

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Publisher

IT LANDS WITH a thunk, from nowhere, out of time, out of order, thrown from the future or perhaps from the past, but landing here, in this place, at this moment, which could be any moment, which means, you guess, it’s no moment.

It appears to be a film.

HERBERT AND DUNHAM RIDE BICYCLES (1896)

HERBERT ’N’ ME is ridin’ bi-cycles over to Anastasia Island. They got that new bridge now. It’s November 30, 1896, and almost dark but not just yet. I don’t know ’zactly the weather because they don’t got records this far back, but it’s Florida, so it’s probably warm, no matter when. Anyways, we’s yippin’ an’ hollerin’ and whatnot, the things young boys do, on account of us being just that, and full of beans to boot. I’m about to tell a tall tale to Herbert about a ghost on account of I know he spooks easy and it’s always fun to try ’n’ get a rise outta him. Herbert an’ me, we met on account of the Sisters taking us both in when we was real little cuz we was orphan babies that got found right in the Tolomato grave yard, no lie, which is itself pretty spooky, if ya think about it. So the Sisters, they took us in and that’s how we met, and now we’re both adopted by the Widow Perkins, who is old and lonesome and she wanted some boys around to make her feel young again an’ not so alone, she says. But that’s not here nor there as we ride our bi-cycles toward Crescent Beach on account of the fishin’ is good there for croakers. It’s still not dark and we grab our poles and leave our bi-cycles and make our way down to the water.

“What’s that?” says Herbert.

I don’t rightly know, but since I been plannin’ on spookin’ him anyways, I say, “Maybe a spook, Herbert.”

Now, Herbert wants to hightail it back to town when he hears that, so I tell him I’m only just foolin’ and t’ain’t no such thing as a spook in truth, and that seems to convince him it might could be worthwhile to get closer and investigate.

Herbert agrees with some trepidatiousness to proceed to the lump, for that’s what it appears to be, a lump.

Well, sir, it is large! I’m no measurin’ expert, but I’m guessin’ it has to be twenty feet long and ten feet wide. It has four arms. It’s white and feels rubbery hard like the soles of the Colchester athletic shoes Widow Perkins bought me for my last birthday at which I was ten. Herbert won’t touch the thing, but I can’t keep my hands off it.

“What do you s’pose it is?” Herbert says.

“I don’t know, Herbert,” I say. “What has the mighty sea thrown up to us? Who can know what lurks in the inky dark, black murkiness of the sea? It’s kind of like a, what do you call it, metaphor for the human mind in all its unknowability.”

Herbert nods, bored. He’s heard this all before. Even though we’re close as real brothers, we are very different. Herbert is not interested in matters of the spirit or mind. One might say he’s more of a pragmatis’, truth be told. But he puts up with my speculatin’, and I love him for indulgin’ me. So I continue: “The Bible that the Sisters learnt us at the orphanage is chock-full of fish symbolism, and from what I heared, there’s fish in almost all mythological traditions, be they from the Orient or otherwise. Fact, from what I been told, there’s a young Swizzerland feller name of Carl Young, who believes fish is symbolic of the unconscious—is it unconscience or unconscious? I can never remember.”

Herbert shrugs.

“Anyhow,” I continue, “makes me think of that feller Jonah from the Jew Bible. He gets himself swallowed by a giant fish on account of he’s shirkin’ what God wants of him. After a spell, God has that fish vomit him out on the shore. Now we have this fish vomited out here on our shore. Is this the opposite of Jonah? Did God have some giant human feller swallow this fish just to throw him up here? I know the Bible is not s’posed to be read literal-like but more like, what do you call it, allegorical and what have you. But here we are with a giant mysterious fish-thing. And it has four arms! Like a fish dog. Or half a octopus. Or two-thirds a ant. It’s mysterious!”

I look at Herbert. He’s absently poking the monster with a stick.

“C’mon,” I say. “Let’s tie it to our bi-cycles with seaweed strands and pull it to town.”

Now, Herbert likes a task as much as anyone, so his eyes light up and we set to work. Once the whole thing is secured, we get on our bi-cycles and try to ride away. The seaweed snaps pretty quick, causing Herbert and me to fly off our bi-cycles into a ditch, which tells me the sea monster is heavier than we originally figgered. I’m no expert on weights or measurements, as I told you.

It’s Herbert’s idea to go an’ get Doc Webb from town. He’s the educatedest man in St. Augustine and an expert in the workings of the natural world. He’s also the doctor at the Blind and Deef School, and that’s where we find him, taking the temperchers of two little boys with no eyes.

“What’s up, fellas?” he asks, to us, not the blind boys, which I guess he already knows the answer to.

“We thought you might wanna know we discovered a sea monster just now on the Crescent Beach,” I say, all puffed up and such.

“Is this true, Herbert?” Doc Webb asks Herbert.

Herbert nods, then adds, “We believe it’s from the Jew Bible and such.”

This isn’t exactly true, but I’m surprised Herbert heared even that much.

“Well, I can’t investigate till tomorrow. There’s an entire dormitory of eyeless children whose vital signs need measuring and recording. Not to mention the earless children across campus.”

An’ as Doc Webb hurries off to attend to his duties, sumthin’ strikes me an’ it strikes me so hard it damn near knocks me off my feet.

“Herbert,” I say. “What if that mound of stuff was us?”

“Like how?” asks Herbert.

“Like, say there was many of us—”

“Of you and me?”

“Yes. You and me, but ’cept babies of us from the future, that get all jammed up together in their travel back in time to now, all jammed together into one, single unholy monstrosity of flesh. So that maybe it ain’t no sea monster on the beach at all, but just us?”

“You and me?”

“Just a notion. But it makes a feller wonder.”

CHAPTER 1

MY BEARD IS a wonder. It is the beard of Whitman, of Rasputin, of Darwin, yet it is uniquely mine. It’s a salt-and-pepper, steel-wool, cotton-candy confection, much too long, wispy, and unruly to be fashionable. And it is this, its very unfashionability, that makes the strongest statement. It says, I don’t care a whit (a Whitman!) about fashion. I don’t care about attractiveness. This beard is too big for my narrow face. This beard is too wide. This beard is too bottom-heavy for my bald head. It is off-putting. So if you come to me, you come to me on my terms. As I’ve been bearded thusly for three decades now, I like to think that my beard has contributed to the resurgence of beardedness, but in truth, the beards of today are a different animal, most so fastidious they require more grooming than would a simple clean shave. Or if they are full, they are full on conventionally handsome faces, the faces of faux woodsmen, the faces of home brewers of beer. The ladies like this look, these urban swells, men in masculine drag. Mine is not that. Mine is defiantly heterosexual, unkempt, rabbinical, intellectual, revolutionary. It lets you know I am not interested in fashion, that I am eccentric, that I am serious. It affords me the opportunity to judge you on your judgment of me. Do you shun me? You are shallow. Do you mock me? You are a philistine. Are you repulsed? You are … conventional.

That it conceals a port-wine stain stretching from my upper lip to my sternum is tertiary, secondary at most. This beard is my calling card. It is the thing that makes me memorable in a sea of sameness. It is the feature in concert with my owlish wire-rim glasses, my hawkish nose, my sunken blackbird eyes, and my bald-eagle pate that makes me caricaturable, both as a bird and as a human. Several framed examples from various small but prestigious film criticism publications (I refuse to be photographed for philosophical, ethical, personal, and scheduling reasons) adorn the wall of my home office. My favorite is an example of what is commonly known as the inversion illusion. When hung upside down, I appear to be a Caucasian Don King. As an inveterate boxing enthusiast and scholar, I am amused by this visual pun and indeed used the inverted version of this illustration as the author photo for my book The Lost Religion of Masculinity: Joyce Carol Oates, George Plimpton, Norman Mailer, A. J. Liebling, and the Sometimes Combative History of the Literature of Boxing, the Sweet Science, and Why. The uncanny thing is that the Don King illusion works in reality as well. Many’s the time, after I perform sirsasana in yoga class, that the hens circle, clucking that I look just like that “awful boxing man.” It’s their way of flirting, I imagine, these middle-aged, frivolous creatures, who traipse, yoga mat rolled under arm or in shoulder-holster, announcing their spiritual discipline to an uncaring world—from yoga to lunch to shopping to loveless marriage bed. But I am there only for the workout. I don’t wear a special outfit or listen to the mishmash Eastern religion sermon the instructor blathers beforehand. I don’t even wear shorts and a T-shirt. Gray dress pants and a white button-down shirt for me. Belt. Black oxfords on feet. Wallet packed thickly into rear right pocket. I believe this makes my point. I am not a sheep. I am not a faddist. It’s the same outfit I wear if on some odd occasion I find myself riding a bicycle in the park for relaxation. No spandex suit with logos all over it for me. I don’t need anyone thinking I am a serious bicycle rider. I don’t need anyone thinking anything of me. I am riding a bike. That is it. If you want to think something about that, have at it, but I don’t care. I will admit that my girlfriend is the one who has gotten me on a bike and into the yoga classroom. She is a well-known TV actress, famous for her role as a wholesome but sexy mom in a 1990s sitcom and many television movies. You would certainly know who she is. You might say I, as an older, intellectual writer, am not “in her league,” but you’d be mistaken. Certainly when we met at a book signing of my prestigious small-press critical biography of—

Something (deer?) dashes in front of my car. Wait! Are there deer here? I feel like I’ve read that there are deer here. I need to look it up. The ones with fangs? Are there deer with fangs? I think there is such a thing—a deer with fangs—but I don’t know if I’ve imagined it, and if I haven’t, I don’t know why I associate them with Florida. I need to look it up when I arrive. Whatever it was, it is long gone.

I AM DRIVING through blackness toward St. Augustine. My mind has wandered into the beard monologue, as it so often does on long car trips. Trips of any kind. I’ve delivered it at book signings, at a lecture on Jean-Luc Godard at the 92nd Street Y Student Residence Dining Hall Overflow Room. People seem to enjoy it. I don’t care that they do, but they do. I’m just sharing that piece of trivia because it’s true. Truth is my master in all things, if I can be said to have a master, which I cannot. Ninety degrees, according to the outside temperature gauge on my car. Eighty-nine percent humidity, according to the perspiratory sheen on my forehead (at Harvard, I was affectionately known as the Human Hygrometer). A storm of bugs in the headlights, slapping the windshield, smeared by my wipers. My semiprofessional guess is a swarm of the aptly named lovebug—Plecia nearctica—the honeymoon fly, the double-headed bug, so called because they fly conjoined, even after the mating is complete. It is this kind of postcoital cuddling I find so enjoyable with my African American girlfriend. You would recognize her name. If the two of us could fly through the Florida night together thusly, I would in a second agree to it, even at the risk of splattering against some giant’s windshield. I find myself momentarily lost in that sensual and fatal scenario. An audible splat wakes me from this diversional road trip reverie, and I see that a particularly large and bizarre insect has smashed into the glass, smack in the center of what I estimate is the northwest quadrant of the windshield.

The highway is empty, the nothingness on either side of me interrupted by an occasional fluorescent fast-food joint, open but without customers. No cars in the parking lots. The names are unfamiliar: Slammy’s. The Jack Knife. Mick Burger. Something sinister about these places isolated in the middle of nothing. Who are they feeding? How do they get their supplies? Do frozen-patty trucks come here from some Slammy’s warehouse somewhere? Hard to imagine. Probably a mistake to drive here from New York. I thought it would be meditative, would give me time to think about the book, about Marla, about Daisy, about Grace, about how far I seem to be from anything I’d ever envisioned for myself. How does that happen? Can I even know who I was before the world got its hands on me and turned me against myself into this … thing?

Anyway, it’s ancient history, to quote every schmo and his brother. There is no way to know. Random speculation after a meager archaeological dig. Where does this anger come from? Why am I crying? Why do I love that woman at Whole Foods? Even after they were acquired by Amazon, I still love her, even though I know Amazon is all that is wrong with this world. Well, not all. Bezos is still working on all. What am I trying to prove? What the fuck am I trying to prove? And I move further into the future, further from when this cracked clay vessel was new, when its purpose was clear, when it was designed to hold a specific long-forgotten thing. What hurt was it made to hold? What embarrassment? What loss? What, dare I speculate, joy? What unmet need forever put away? Here I am on the far side of fifty with no hair on my head and an unkempt gray beard, driving through the night to research a book about gender and cinema, a book that will pay me nothing and be read by no one. Is this what I want to be doing? Am I who I want to be? Do I really want this ridiculous face, which, according to the wags, I deserve? No. And yet, here it is. What I want is to be whole. I want to not hate myself. I want to be pretty. I want my parents to love me a million years ago in ways that they probably didn’t. Maybe they did. I think they did, but I can find no other explanation for this constant need, this unfillable hole, this conviction that I am repulsive, pathetic, disgusting. I search every face for some indication to the contrary. Pleadingly. I want them to look at me the way I look at those women, the ones who walk by not seeing me. Haughty and autonomous. Maybe this is why I have the beard. It is protesting too much. It says, I don’t need you to love me, to be attracted to me, and here’s how I will demonstrate that. I will look like a ridiculous intellectual. I will look dirty, as if perhaps I smell. When I was younger, I held out some hope that I would transform into something attractive. The ugly duckling lie they force-feed sad, unattractive children the way they force-feed corn to the pâté geese. I went to the gym. I ran. I bought some hip clothing. Wide belts were in fashion. I bought the widest belts I could find. I had to go all the way to Lindenhurst to procure them. I had my loops specially enlarged by a tailor in Weehawken who did similar work for David Soul. But the hair disappeared and the face got old and there was no point in denying it, so I went the other way. Maybe I could look wise. Maybe my rheumy eyes behind thick magnifying lenses would appear thoughtful and even kind. This was the best I could hope for. And it certainly got me seen. No doubt there were snickers behind my back, but my persistence illustrated my defiance of the standard model, my independence.

And it worked in some small ways. My current girlfriend, the one who ended my marriage, is an actress, beautiful, the star of a nineties sitcom, you’d definitely know her. I believe she was attracted to my rebellious, intellectual look. And to my last book. She is African American, not that that’s important, but I certainly never expected it to happen. I never imagined there’d be any interest in me from an African American woman. I am in no way, shape, or form a supermasculine menial, and she is quite beautiful and fifteen years my junior. She read my book on William Greaves and his film Symbiopsychotaxiplasm. She wrote a fan letter. You’d know who she is. She’s very beautiful. I won’t say her name. We met, and suddenly my difficult marriage became an unbearable one. This African American woman was everything I had ever wanted and didn’t think possible. She’s been in several movies as well. Movies I’ve explored in my own writings. Movies in which I’ve given her favorable mention. She is obviously well-read. She is funny, and our conversation is like lightning: witty, intense, emotionally naked. Often we talk through the night, fueled by coffee, cigarettes (which I gave up years ago but inexplicably find myself smoking when with her), and sex. I didn’t know I could get erections like this anymore. The first night I couldn’t get it up because I imagined she was comparing me to the stereotypical African American man’s anatomy and I was self-conscious and ashamed. But we talked through that. She explained to me that she’d been with both meagerly and well-endowed black men, that there was something inherently racist about my assumption, that I needed to investigate it straight on. She went on to say that size is not important anyway. It is how a man uses his penis, his mouth, his hands. It is the love with which he engages that is the ultimate aphrodisiac, she explained. She ended by saying I needed to check my privilege, which did not seem to be the issue at hand, but about that she was undoubtedly correct. She is a wise African American woman and exceedingly sensual. Everything she does in the world, from tasting, to bathing, to looking, to sex, is done with the most immediacy I’ve ever witnessed from another human. I have much to learn from her.

Over the decades, I have erected walls that must be torn down. She’s told me this, and I am trying. I’m taking yoga with her and I always make sure to position myself behind her so I can watch her amazing African American ass. It’s hard to believe I get to touch that. And she’s enrolled us in some sort of tantric weekend retreat, which happens in July and about which I am nervous. Ejaculatory mastery is important, but I’m not certain how comfortable I will be engaging tantrically with strangers. My girlfriend has participated in this workshop before and says it is life-changing, but I am not comfortable being naked among strangers. It is not only my penis-size issue, which I’m working on (that is to say, I’m working on my concern), but it is my body-hair issue. It is not considered attractive these days for men (or women, let’s not get started on that sexist double standard, on that adult-woman-pretending-to-be-prepubescent societal nightmare) to have body hair at all, let alone excessive body hair. I refuse to participate in the culture of waxing or depilation. I view it as vain and unmanly, so consequently I am left self-conscious. My girlfriend says the workshop will do wonders for our sex life and that is a good thing, but I can’t help thinking this means she is dissatisfied. She says she is not, that this is about spiritual communion and freedom from fear, and I guess I accept that. It’s just this relationship means the world to me due to its newness and, I admit, its exotic nature. There’s a lot to think about and the lovebugs keep slapping the windshield. The wipers don’t seem to be working anymore. They just spread the bugs around. I look for a gas station or even a Slammy’s where I could get some water and a napkin. But there is nothing. Just blackness.

Tell me how it begins.

In a car. I am driving. Me but not me. You know what I mean? Night. Dark. Black, really. An empty black highway lined with black trees. Constellations of moths and hard-shelled insects in my headlights smack the windshield, leave their insides. I fiddle with the radio dial. I’m nervous, jittery. Too much coffee? First Starbucks, then Dunkin’ Donuts. Of course Dunkin’ Donuts makes the better coffee. Starbucks is the smart coffee for dumb people. It’s the Christopher Nolan of coffee. Dunkin’ Donuts is lowbrow, authentic. It is the simple, real pleasure of a Judd Apatow movie. Not showing off. Actual. Human. Don’t compete with me, Christopher Nolan. You will always lose. I know who you are, and I know I am the smarter of us. Nothing on the dial for a long span. Then staticky Cuban pop. My fingers tap the wheel. Out of my control. Everything is moving, alive. Heart pounding, blood coursing. Sweat beading on brow, sliding. Then a preacher: “You will keep on hearing but not understand, and you will keep on seeing but not perceive.” Then nothing. Then the preacher. Then nothing. Bugs continue to splat in the staticky nothing. Then the preach—I turn off the preacher. The tires hum. It is so dark. Starting to drizzle. How is that done? How does he make the rain fall? A miracle of craft. Another illusion. The beauty of the world created through practice, over decades, through trial and error. Up ahead, a fluorescent blast of light. Fast-food joint. Slammy’s. Slammy’s in the middle of nothing. In the middle of nowhere. In the middle of drizzle and windshield wipers and bugs and black. Slammy’s. The parking lot is empty; the restaurant is empty. Open but empty. I’ve never heard of Slammy’s in the real world. There’s something disquieting about unfamiliar fast-food places. They’re like off-brand canned goods on a supermarket shelf. Neelon’s Genuine Tuna Fish scares me whenever I see it. I never get used to it. I can never bring myself to buy Neelon’s Genuine Tuna Fish, even though it promises it’s line caught, dolphin safe, canned in spring water, new and improved texture. There have been several of these mystery fast-food places along this road: The Jack Knife. Morkus Flats. Ipp’s. All empty. All glowing. Who eats there? Maybe these restaurants are less foreboding during daylight.

In any event, I slow and pull into the lot. The bugs on my windshield have almost completely obscured my vision. I see but do not perceive anything—but bugs. I hear but do not understand—bugs. I need napkins and water. An African American teenager in a carnival-colored uniform pokes her head suspiciously out from the kitchen at the sound of my tires on their gravel. I park and make my way toward her. She watches me, heavy-lidded.

“Welcome to Slammy’s,” she says, clearly meaning nothing of the kind. “How may I help you?”

“Hello. I just need to use the facilities,” I say as I head for the head.

I chuckle at my mental play on words. I make a note to use this somewhere, perhaps at my upcoming lecture for the International Society of Antique Movie Projector Enthusiasts (ISAMPE). They’re a fun crowd.

The men’s room is a nightmare. One wonders what people do in public restrooms that results in feces spread on the walls. And it is not an uncommon occurrence. Yet how? The stench is unbearable, and there are no paper towels, only one of those hand-blower machines, which I despise because it means there is no way for me to turn the doorknob without touching the doorknob, which I never want to touch.

I turn it using my left hand’s thumb and pinkie.

“Left thumb and pinkie,” I say, to cement in my brain which fingers I should not rub my eyes with or stick in my mouth or nose until I can find proper soap and water.

“I was just hoping for some water and paper towels. For my windshield,” I say to the African American teenager.

“You gotta purchase something.”

“OK. What do you recommend then?”

“I recommend you gotta purchase something, sir.”

“All right. I’ll have a Coke.”

“Size?”

“Large.”

“Small, Medium, Biggy.”

“Biggy Coke? That’s a thing?”

“Yes. Biggy Coke.”

“Biggy Coke, then.”

“We don’t have Coke.”

“OK. What do you have?”

“Slammy’s Original Boardwalk Cola. Slammy’s Original Boardwalk Root—”

“OK. Cola.”

“What size?”

“Large.”

“Biggy?”

“Yes, Biggy. Sorry.”

“What else?”

I want her to like me. I want her to know I’m not some privileged asshole racist Jew northerner. First of all, I have an African American girlfriend. I want her to know that. I don’t know how to bring it up in the context of this conversation, this early in our relationship. But I feel her loathing and want her to know I’m not the enemy. I also want her to know I am not Jewish. There is an historical tension between the African American and Jewish communities. It has been my curse to look Jewish. It’s why I use my credit card whenever I can. I will use it to buy the Slammy’s cola. Maybe then my wallet can accidentally open to the photo of my African American girlfriend. And she’ll see my last name is Rosenberg. Not a Jewish name. Well, not only a Jewish name. Will she even know that it’s not only? It’s wrong for me to assume she’s uneducated. That’s racist. I need to check my privilege at the door, as my African American girlfriend is fond of saying. Still, I have come across many people of various racial and ethnical makeups who have not known that Rosenberg is not a Jewish name, well, not only. I’ve assumed they knew. But later in conversation, they would bring up the Holocaust or dreidels or gefilte fish, trying to be nice, to connect. And I use that opportunity to tell them that Rosenberg is in fact a German—