Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "The Girl in the Mirror"

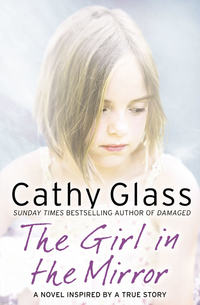

The Girl in the Mirror

A NOVEL INSPIRED BY A TRUE STORY

Cathy Glass

SUNDAY TIMES BESTSELLING AUTHOR

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Author’s Note

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Also by Cathy Glass

Copyright

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

Most families have secrets – skeletons in the closet that are never spoken of. Sometimes the secret is so painful, and buried so deep, that it becomes ‘forgotten’ by the family.

This is the story of Mandy, who wasn’t aware she held the key to her family’s dreadful secret until a crisis unlocked it.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Attitudes to the administering of pain relief are slowly changing.

Prologue

‘I’m sorry,’ Mandy said, stopping Adam’s hand from going any further. ‘I’m sorry. I can’t. Not now.’

‘It’s OK,’ he said a little too quickly, moving away. ‘I could do with an early night.’

She watched him cross her bedsitting room to the chair where he’d left his jacket. Throwing his jacket over his shoulder he continued to walk away from her – to the door. Stop him, now, Mandy told herself. Stop him before it’s too late. ‘Adam?’ she said.

He turned. ‘Yes?’

She hesitated, and then shrugged. ‘Nothing. I’ll see you tomorrow?’

He gave a non-committal half-nod. ‘I’ll phone.’

She watched helplessly as he let himself out. Idiot! she cursed herself. Go after him and try to explain. You’ve done this once too often. It’ll serve you right if he makes it the last time and you lose him for good. But even if she went after him what could she say? She didn’t understand why she behaved as she did, so how could she possibly explain it to him?

Tears stung the back of her eyes. She stood up, moved away from the bed and slowly crossed to the easel propped against the far wall. She stared at the canvas on it. It was entirely blank: an added testament to her failure. Failure as an artist; failure as a lover; failure as a daughter; failure even as a person. Her life was one long failure. She picked up the paintbrush and, deep in thought, stood for a moment holding it at either end, absently flexing the wood. It bent, and then snapped in two. The sound of splintering, cracking wood was satisfying in its finality. It was broken and could never be repaired.

One

Mandy woke with a start. The room was not as it should be; she could sense it. Something had woken her – something close and imminent. Something wrong? She raised her head and looked around. The room was empty, as it should be. Adam had gone and although he had a key he would never use it without asking her first.

Yet something had disturbed her. It was too early for her to wake naturally. The room wasn’t properly light yet, and even the weakest of suns came through the thin and faded curtains. And the street noise filtering through the ill-fitting Victorian sash windows of her bedsitting room suggested very early morning. Mandy turned on to her side and reached over the edge of the bed for her phone. Bringing it to her eyes she peered at the time: 6.29 a.m.

What sounded like hailstones landed against the window and she guessed it was the hail that had woken her. Another wet day, she thought, and to make it worse she’d argued with Adam. She closed her eyes again and hoped the day would go away. No rain followed the hail. She heard a car door slam and the engine start, and a lone police siren in the distance. Then another blast of hail.

A pattern of sound began to emerge as Mandy lay enfolded in her duvet, eyes closed, trying to keep the day at bay. A blast of hail, sand-like against the window, then silence, then another blast of hail. It gradually occurred to her in the half-light of her thoughts and consciousness that the pattern of noise was too regular, too neatly spaced to be hail. She decided it was more likely to be Nick from the attic flat, having locked himself out. As he’d done once before he was now throwing gravel against her window to wake her to let him in, rather than pressing the main doorbell and incurring the wrath of the whole house – six residents in self-contained bedsits, or studio flats as the landlord liked to call them.

Why Nick didn’t secrete a spare front-door key in the garden, as she had done, Mandy didn’t know, but would shortly ask. She knew he had a spare key for the door to his room hidden not very imaginatively under the mat outside his door, but that key was obviously useless if he couldn’t get in the outer door first. It crossed her mind to leave him there a while longer to teach him a lesson. But Nick had been helpful in the past – changing a light-bulb for her which had rusted into its socket, and disposing of a large spider lodged in a crevice of the window and out of her reach. Living this semi-communal existence had one advantage, she thought: they helped each other; that, and it went with the bohemian lifestyle she’d chosen to try and make it as an artist.

With a sigh Mandy left the warmth of her duvet and felt the cold air bite as she crossed the room to the bay window. One of the disadvantages of this lifestyle, she quickly acknowledged, was that feeding the electricity meter for heating had to be discretionary – almost a luxury. Easing back one of the curtains she looked down on to the front path to check it was Nick and not their local down-and-out hoping for a hot drink and a bed, as had happened once before. From her first-floor room she had a clear view over the front garden and path. The only place she couldn’t see was the porch – where Nick must now be, for the path and garden were empty.

She continued to look down, waiting for Nick to reappear. A moment later a man stepped from the porch and stooped to pick up more gravel. It wasn’t Nick but her father!

‘What!’ Mandy exclaimed out loud, and tapped on the window to catch his attention. Whatever was he doing here?

Arrested half into the act of picking up another handful of gravel, her father looked up and, seeing her, straightened. He mouthed something she didn’t understand, then he pointed to the front door and she nodded.

Dropping the curtain, she crossed the room and pulled her kimono dressing gown from the top of the dressing screen. What the hell? she thought again as she tied the kimono over her pyjama shorts and T-shirt. Her parents hadn’t been anywhere near her bedsit (or her bohemian lifestyle, come to that) since she’d taken a year off from teaching art to follow her dream of becoming an artist and paint full time. Now, here was her father, throwing gravel at her window to wake her at 6.30 a.m.! Shrugging off the last of her sleep she realized with a stab of panic something had to be wrong, badly wrong. And given it was her father who was here and not her mother, something must have happened to her mother!

Mandy’s heart raced as she ran down the threadbare carpet of the wide Victorian staircase. Arriving in the hall she turned the doorknob and heaved open the massive oak front door. ‘Mum?’ she gasped, searching his face. His expression seemed to confirm her worst fears.

‘No, your mother’s fine,’ he said sombrely. ‘I’m afraid it’s your grandpa, Amanda. He’s taken a turn for the worse.’

‘Oh…’

‘He has left hospital and has gone to your aunt’s. I am going there now.’

‘Oh, oh, I see,’ she said, relief that her mother was safe and well quickly turning to anxiety that dear Grandpa was very ill.

‘I thought, as you’re not working, you’d like to come with me,’ her father continued. ‘Your mother prefers not to go while Grandpa’s staying at your aunt’s.’

This came as no surprise to Mandy for, while her mother got on well with her in-laws, ten years previously there’d been what her father had called ‘a situation’, which had resulted in her parents severing all contact with Aunt Evelyn, Mandy’s father’s sister, and Evelyn’s family. Now, ten years on, and with no contact in the interim, her father was going to his estranged sister’s house! Mandy knew he would never have gone had his father not been ill and staying there; and her mother was still refusing to go.

‘Yes, I’ll come,’ Mandy said quickly. ‘I’d like to. I didn’t realize Grandpa was so ill.’

‘Neither did I. Your aunt phoned late last night.’

As he came in and Mandy closed the door behind him, she tried to picture the stilted conversation that must have taken place between her father and his sister – their first conversation in ten years. She wondered if her mother had spoken to her sister-in-law and decided probably not.

‘Is Grandpa very ill?’ she asked once they were in her room.

‘Your aunt said so,’ her father said stiffly.

‘So why is he at Evelyn’s and not in hospital?’

‘He was in hospital but your aunt had him discharged. She said she could look after him better at her home than the hospital could. Your gran agreed. She’s staying at your aunt’s too.’

‘I see, and what have the doctors said?’ Mandy felt fear creeping up her spine.

‘I’m not sure; we’ll find out more today.’ He thrust his hands into his trouser pockets and shrugged. ‘I don’t know, perhaps your mother was right and Evelyn is being hysterical, but I have to go and see him just in case…’

Mandy decided to make do with a quick wash rather than her normal shower so she turned on the hot tap, which produced its usual meagre trickle of lukewarm water. ‘Sit down, Dad,’ she said. ‘You haven’t seen my bedsit before. What do you think?’

In the mirror above the basin she saw him cast a gaze over the 1950s furniture, which had clearly given good service. He gave a reserved nod. ‘Is all this yours?’

‘No, it came with the room. Apart from that Turkish rug. And I bought a new mattress for the bed.’ She squeezed out the flannel and ran it over her face and neck. ‘Would you like coffee?’

‘No, thank you. I had one before I left.’

Taking the towel from the rail, she patted her face and neck dry and then crossed to the chest of drawers where she took out clean underwear, trainer socks and T-shirt. Collecting her jeans from where she’d dropped them on the floor the night before, she disappeared behind the Japanese-style dressing screen. In one respect it was just as well Adam had gone off in a huff the night before, Mandy thought. It would have been embarrassing if her father had come in to find him in her bed. But she was sorry she’d behaved as she had and if Adam didn’t phone as he said he would she’d phone him – and apologize.

‘Is Mum OK?’ she asked from behind the screen.

‘Yes, though she’s worried about your grandpa, obviously. She sends her love.’

‘And how are Evelyn and John?’

There was a pause. ‘Your aunt didn’t say much really.’

‘I guess it was a difficult call for her to make.’

Through the gap between the panels of the hinged dressing screen, Mandy could see her father. He was sitting in the faded leather captain’s chair, hunched slightly forward, with a hand resting on each knee and frowning.

‘By the way Evelyn spoke,’ he said indignantly, ‘you’d have thought I hadn’t seen my father in years. I told her I’d have visited him in hospital again if he’d stayed.’ Mandy heard the defensiveness and knew the peace between her father and his sister was very fragile indeed and only in place to allow them to visit Grandpa.

Dressed in jeans and T-shirt, she stepped from behind the dressing screen and crossed the room. She threw her kimono and pyjamas on to the bed and went to the fridge. ‘I’m nearly ready, I just need a drink. Are you sure you don’t want something?’

‘No thanks.’ He shook his head.

The few glasses she possessed were in the ‘kitchen’ sink, and to save time, and also because she could in her own place, she drank the juice straight from the carton. ‘Ready,’ she said, returning the juice to the fridge. She wiped her mouth on a tissue and threw it in the bin.

Her father stood and followed her to the door. ‘Have you painted many pictures?’ he asked, nodding at the empty easel.

Mandy saw the broken paintbrush and wondered if he’d seen it too. ‘Yes,’ she lied. She took her bag from the hook behind the door and threw it over her shoulder. ‘Yes, it was the right decision to give up work. I have all the time in the world to paint.’ Which was true, but what she couldn’t tell him or Adam – indeed could barely admit to herself – was that in the seven months since she’d given up work she’d painted absolutely nothing, and her failure in this had affected all other aspects of her life. So much so that she’d lost confidence in her ability to do anything worthwhile, ever again.

Two

Checking her mobile, Mandy got into her father’s car. There was no message from Adam but he would only just be up. She fastened her seatbelt as her father got in. On a weekday Adam left his house at 7.30 a.m. to catch a train into the City. Her heart stung at the thought of how she’d rejected him and she now longed for the feel of his arms around her. Bringing up a blank text she wrote: Im rly rly sorry. Plz 4giv me. Luv M, and pressed Send. She sat with the phone in her lap; her father started the engine and they pulled away. A minute later her phone bleeped a reply: U r 4given. C u l8r? A x. Thank God, she thought. She texted back: Yes plz. Luv M. Returning the phone to her bag, she relaxed back and looked at the road ahead.

It felt strange sitting beside her father in the front of the car as he drove. Despite the worry of Grandpa being ill, it felt special – an occasion – an outing. Mandy couldn’t remember the last time she’d sat in the front of a car next to her father. When she’d travelled in the car as a child her place had always been in the back, and later it had been her mother who’d taken her to and collected her from university. When she’d started work she’d bought a car of her own which she’d sold to help finance her year out. No, this was definitely a first, she thought. I don’t think I’ve ever sat in the front next to Father.

‘The hospital was pretty grim,’ her father said, breaking into her thoughts. ‘Apparently it’s a brand-new building, but staffed by agency nurses. Your aunt said there was no continuity of care and your grandfather was left unattended. She suggested they paid for him to go into a private hospital but your grandfather wouldn’t hear of it.’

Mandy smiled. ‘That’s my grandpa!’ Like her father, he was a man of strong working-class principles and would have viewed going private as elitist or unfair. She noticed her father referred to his sister as ‘your aunt’ rather than using her first name, which seemed to underline the distance which still separated them.

‘I expect he wanted to be out of hospital,’ Mandy added. ‘It’s nice to be with your family if you’re ill.’

‘Perhaps,’ he said. ‘As long as he’s getting the medical care he needs.’

She nodded.

‘It’s good weather for the journey,’ he said a moment later, changing the subject. ‘Not a bad morning for March.’

March, she thought. She was over halfway through her year out – five months before the money ran out and she would have to return to the classroom.

‘Does Sarah still live at home?’ Mandy asked presently as the dual carriageway widened into motorway.

‘I don’t know, your aunt didn’t say.’

‘It would be nice to see her again after all these years. I wonder what she’s doing now.’

Mandy saw his hands tighten around the steering wheel and his face set. She hadn’t intended it as a criticism, just an expression of her wish to see Sarah again, but clearly he had taken it as one. When her father had fallen out with his sister ten years ago and all communication between the two families had ceased, Mandy had been stopped from seeing her cousin Sarah, which had been very sad. They were both only children and had been close, often staying at each other’s houses until ‘the situation’ had put a stop to it.

‘It was unavoidable,’ he said defensively. ‘It was impossible for you to visit after…You wouldn’t know, you don’t remember. You were only a child, Amanda. It should never have happened and I blame myself. I vowed we’d never set foot in that house again. If it wasn’t for Grandpa being taken there, I wouldn’t, and I’ve told Evelyn that.’

Mandy felt the air charged with the passion of his disclosure. It was the most he’d ever said about ‘the situation’, ever. Indeed, it had never been mentioned by anyone in the last ten years, not in her presence at least. Now, not only had he spoken of it, but he appeared to be blaming himself, which was news to her. And his outburst – so out of character – and the palpable emotion it contained made Mandy feel uncomfortable, for reasons she couldn’t say.

She looked out of her side window and concentrated on the passing scenery. It was a full ten minutes before he spoke again and then this voice was safe and even once more.

‘There’s snow forecast for next week,’ he said.

‘So much for global warming!’

A few minutes later he switched on Radio 3, which allowed Mandy to take her iPod from her bag and plug in her headphones. It was a compilation – garage, hip-hop, Mozart and Abba; Mandy rested her head back and allowed her gaze to settle through the windscreen. The two-hour journey slowly passed and her thoughts wandered to the trips she’d made to and from her aunt’s as a child. The adults had taken turns to collect and return Sarah and her from their weekend stays. Mandy remembered how they’d sat in the back of the car and giggled, the fun of the weekend continuing during the journey. Then the visits had abruptly stopped and she’d never seen Sarah again. Stopped completely without explanation, and she’d never been able to ask her father why.

They turned off the A11 and Mandy switched off her iPod and removed her earpieces.

‘Not far now,’ her father said.

She heard the tension in his voice and saw his forehead crease. She wasn’t sure how much of his anxiety was due to Grandpa’s illness, and how much by the prospect of seeing his sister again, but Mandy was sure that if she hadn’t agreed to accompany him, or her mother hadn’t changed her mind and come, he would have found visiting alone very difficult indeed. His dependence on her gave him an almost childlike vulnerability, and her heart went out to him.

‘Don’t worry,’ she said lightly. ‘I’m sure Evelyn will be on her best behaviour.’

He smiled and seemed to take comfort in their small conspiracy. ‘We won’t stay too long,’ he reassured her.

They slowed to 30 m.p.h. as they entered the village with its post-office-cum-general-store. Mandy remembered the shop vividly from all the times she’d stayed at her aunt’s. Auntie Evelyn, Sarah and she had often walked to the store, with Sarah’s Labrador Misty. When Sarah and she had been considered old enough, the two of them had gone there alone to spend their pocket money on sweets, ice-cream, or a memento from the display stand of neatly arranged china gifts. It had been an adventure, a chance to take responsibility, which had been possible in the safe rural community where her aunt lived, but not in Greater London when Sarah had stayed with her.

Mandy recognized the store at once – it was virtually unchanged – as she had remembered the approach to the village, and indeed most of the journey. But as they left the village and her father turned from the main road on to the B road for what he said was the last part of the journey, she suddenly found her mind had gone completely blank. She didn’t recall any of it.

She didn’t think it was that the developers had been busy in the last ten years and had changed the contours of the landscape; it was still largely agricultural land, with farmers’ houses and outbuildings dotted in between, presumably as it had been for generations. But as Mandy searched through the windscreen, then her side window, and round her father to his side window, none of what she now saw looked the least bit familiar. She could have been making the journey for the first time for the lack of recognition, which was both strange and unsettling. Swivelling round in her seat, she turned to look out of the rear window, hoping a different perspective might jog her memory.

‘Lost something?’ her father asked.

‘No. Have Evelyn and John moved since I visited as a child?’ Which seemed the most likely explanation, and her father had forgotten to mention it.

‘No,’ he said, glancing at her. ‘Why do you ask?’

Mandy straightened in her seat and returned her gaze to the front, looking through the window for a landmark – something familiar. ‘I don’t recognize any of this,’ she said. ‘Have we come a different way?’

He shook his head. ‘There is only one way to your aunt’s. We turn right in about a hundred yards and their house is on the left.’

Mandy looked at the trees growing from the grassy banks that flanked the narrow road and then through a gap in the trees, which offered another view of the countryside. She looked through the windscreen, then to her left and right, but still found nothing that she even vaguely remembered – absolutely nothing. She heard her father change down a gear, and the car slowed; then they turned right and continued along a single-track lane. Suddenly the tyres were crunching over the gravel and they pulled on to a driveway leading to a house.

‘Remember it now?’ she heard him say. He stopped the car and cut the engine.

Mandy stared at the house and experienced an unsettling stab of familiarity. ‘A little,’ she said, and tried to calm her racing heart.