Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "The Ice Princess"

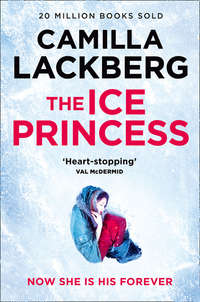

CAMILLA LACKBERG

The Ice Princess

Translated from the Swedish by

Steven T. Murray

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2008

Copyright © Camilla Lackberg 2004

Published by agreement with Bengt Nordin Agency, Sweden

English translation © Steven T. Murray 2007

Cover design by Heike Schüssler © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © Aleah Ford/Arcangel (woman); Shutterstock (ice)

Fjällbacka map by Andrew Ashton © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2008

Camilla Lackberg asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007416189

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2009 ISBN: 9780007313693

Version: 2017-08-03

Dedication

For Wille

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

The Preacher

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

1

The house was desolate and empty. The cold penetrated into every corner. A thin sheet of ice had formed in the bathtub. She had begun to take on a slightly bluish tinge.

He thought she looked like a princess lying there. An ice princess.

The floor he was sitting on was ice cold, but the chill didn’t bother him. He reached out his hand and touched her.

The blood on her wrists had congealed long ago.

His love for her had never been stronger. He caressed her arm, as if he were caressing the soul that had now left her body.

He didn’t look back when he left. It was not ‘good-bye’, it was ‘until we meet again’.

Eilert Berg was not a happy man. His breathing was strained and his breath came out of his mouth in little white puffs, but his health was not what he considered his biggest problem.

Svea had been so gorgeous in her youth, and he had hardly been able to stand the wait before he could get her into the bridal bed. She had seemed tender, affectionate, and a bit shy. Her true nature had come out after a period of youthful lust that was far too brief. She had put her foot down and kept him on a tight leash for close to fifty years. But Eilert had a secret. For the first time, he saw an opportunity for a little freedom in the autumn of his years and he did not intend to squander it.

He had toiled hard as a fisherman all his life, and the income had been just enough to provide for Svea and the children. After he retired they had only their meagre pensions to live on. With no money in his pocket there was no chance of starting his life over somewhere else, alone. Now this opportunity had appeared like a gift from above, and it was laughably easy besides. But if someone wanted to pay him a shameless amount of money for a few hours’ work each week, that wasn’t his problem. He wasn’t about to complain. The banknotes in the wooden box behind the compost heap had piled up impressively in only a year, and soon he would have enough to be able to move to warmer climes.

He stopped to catch his breath on the last steep approach to the house and massaged his arthritic hands. Spain, or maybe Greece, would thaw the chill that seemed to come from deep inside him. Eilert reckoned that he had at least ten years left before it would be time to turn up his toes, and he intended to make the most of them, so he’d be damned if he’d spend them at home with that old bitch.

His daily walk in the early morning hours had been his only time spent in peace and quiet; it also meant that he got some much-needed exercise. He always took the same route, and people who knew his habits would often come out and have a chat. He particularly enjoyed talking with the pretty girl in the house farthest up the hill by the Håkebacken school. She was there only on weekends, always alone, but she was happy to take the time to talk about the weather. Miss Alexandra was interested in Fjällbacka in the old days as well, and this was a topic that Eilert enjoyed discussing. She was nice to look at too. That was something he still appreciated, even though he was old now. Of course there had been a good deal of gossip about her, but once you started listening to women’s chatter you wouldn’t have much time for anything else.

About a year ago, she had asked him whether he might consider stopping in at the house as long as he was passing by on Friday mornings. The house was old, and both the furnace and the plumbing were unreliable. She didn’t like coming home to a cold house on the weekends. She would give him a key, so he could just look in and see that everything was in order. There had been a number of break-ins in the area, so he was also supposed to check for signs of tampering with the doors and windows.

The task didn’t seem particularly burdensome, and once a month there was an envelope with his name on it waiting in her letter-box, containing what was, to him, a princely sum. He also thought it was nice to feel useful. It was so hard to go around idle after he had worked his whole life.

The gate hung crookedly and it groaned when he pushed on it, swinging it in towards the garden path, which had not yet been shovelled clear of snow. He wondered whether he ought to ask one of the boys to help her with that. It was no job for a woman.

He fumbled with the key, careful not to drop it into the deep snow. If he had to get down on his knees, he’d never be able to get up again. The steps to the front porch were icy and slick, so he had to hold on to the railing. Eilert was just about to put the key in the lock when he saw that the door was ajar. In astonishment, he opened it and stepped into the entryway.

‘Hello, is anybody at home?’

Maybe she’d arrived a bit early today. There was no answer. He saw his own breath coming out of his mouth and realized that the house was freezing cold. All at once he didn’t know what to do. There was something seriously wrong, and he didn’t think it was just a faulty furnace.

He walked through the rooms. Nothing seemed to have been touched. The house was as neat as always. The VCR and TV were where they belonged. After looking through the entire ground floor, Eilert went upstairs. The staircase was steep and he had to grab on hard to the banister. When he reached the upper floor, he went first to the bedroom. It was feminine but tastefully furnished, and just as neat as the rest of the house. The bed was made and there was a suitcase standing at the foot. Nothing seemed to have been unpacked. Now he felt a bit foolish. Maybe she’d arrived a little early, discovered that the furnace wasn’t working, and gone out to find someone to fix it. And yet he really didn’t believe that explanation. Something was wrong. He could feel it in his joints, the same way he sometimes felt an approaching storm. He cautiously continued looking through the house. The next room was a large loft, with a sloping ceiling and wooden beams. Two sofas faced each other on either side of a fireplace. There were some magazines spread out on the coffee table, but otherwise everything was in its place. He went back downstairs. There, too, everything looked the way it should. Neither the kitchen nor the living room seemed any different than usual. The only room remaining was the bathroom. Something made him pause before he pushed open the door. There was still not a sound in the house. He stood there hesitating for a moment, realized that he was acting a bit ridiculously, and firmly pushed open the door.

Seconds later, he was hurrying to the front door as fast as his age would permit. At the last moment, he remembered that the steps were slippery and grabbed hold of the railing to keep from tumbling headlong down the steps. He trudged through the snow on the garden path and swore when the gate stuck. Out on the pavement he stopped, at a loss what to do. A little way down the street he caught sight of someone approaching at a brisk walk and recognized Tore’s daughter Erica. He called out to her to stop.

She was tired. So deathly tired. Erica Falck shut down her computer and went out to the kitchen to refill her coffee cup. She felt under pressure from all directions. The publishers wanted a first draft of the book in August, and she had hardly begun. The book about Selma Lagerlöf, her fifth biography about a Swedish woman writer, was supposed to be her best, but she was utterly drained of any desire to write. It was more than a month since her parents had died, but her grief was just as fresh today as when she received the news. Cleaning out her parents’ house had not gone as quickly as she had hoped, either. Everything brought back memories. It took hours to pack every carton, because with each item she was engulfed in images from a life that sometimes felt very close and sometimes very, very far away. But the packing couldn’t be rushed. Her flat in Stockholm had been sublet for the time being, and she reckoned she might as well stay here at her parents’ home in Fjällbacka and write. The house was a bit out of town in Sälvik, and the surroundings were calm and peaceful.

Erica sat down on the enclosed veranda and looked out over the islands and skerries. The view never failed to take her breath away. Each new season brought its own spectacular scenery, and today it was bathed in bright sunshine that sent cascades of glittering light over the thick layer of ice on the sea. Her father would have loved a day like this.

She felt a catch in her throat, and the air in the house all at once seemed stifling. She decided to go for a walk. The thermometer showed fifteen degrees below zero, and she put on layer upon layer of clothing. She was still cold when she stepped out the door, but it didn’t take long before her brisk pace warmed her up.

Outside it was gloriously quiet. There were no other people about. The only sound she heard was her own breathing. This was a stark contrast to the summer months when the town was teeming with life. Erica preferred to stay away from Fjällbacka in the summertime. Although she knew that the survival of the town depended on tourism, she still couldn’t shake the feeling that every summer the place was invaded by a swarm of grasshoppers. A many-headed monster that slowly, year by year, swallowed the old fishing village by buying up the houses near the water, which created a ghost town for nine months of the year.

Fishing had been Fjällbacka’s livelihood for centuries. The unforgiving environment and the constant struggle to survive, when everything depended on whether the herring came streaming back or not, had made the people of the town strong and rugged. Then Fjällbacka had become picturesque and began to attract tourists with fat wallets. At the same time, the fish lost their importance as a source of income, and Erica thought she could see the necks of the permanent residents bend lower with each year that passed. The young people moved away and the older inhabitants dreamed of bygone times. She too was among those who had chosen to leave.

She picked up her pace some more and turned left towards the hill leading up to the Håkebacken school. As Erica approached the top of the hill she heard Eilert Berg yelling something she couldn’t really make out. He was waving his arms and coming towards her.

‘She’s dead.’

Eilert was breathing hard in small, short gasps, a nasty wheezing sound coming from his lungs.

‘Calm down, Eilert. What happened?’

‘She’s lying in there! Dead.’

He pointed at the big, light-blue frame house at the crest of the hill, giving her an entreating look at the same time.

It took a moment before Erica comprehended what he was saying, but when the words sank in she shoved open the stubborn gate and plodded up to the front door. Eilert had left the door ajar, and she cautiously stepped over the threshold, uncertain what she might expect to see. For some reason she didn’t think to ask.

Eilert followed warily and pointed mutely towards the bathroom on the ground floor. Erica was in no hurry. She turned to give Eilert an enquiring glance. He was pale and his voice was faint when he said, ‘In there.’

Erica hadn’t been in this house for a long time, but she had once known it well, and she knew where the bathroom was. She shivered in the cold despite her warm clothing. The door to the bathroom swung slowly inward, and she stepped inside.

She didn’t really know what she had expected from Eilert’s curt statement, but nothing had prepared her for the blood. The bathroom was completely tiled in white, so the effect of the blood in and around the bathtub was even more striking. For a brief moment she thought that the contrast was pretty, before she realized that a real person was lying in the tub.

In spite of the unnatural interplay of white and blue on the body, Erica recognized her at once. It was Alexandra Wijkner, née Carlgren, daughter of the family that owned this house. In their childhood they had been best friends, but that felt like a whole lifetime ago. Now the woman in the bathtub seemed like a stranger.

Mercifully, the corpse’s eyes were shut, but the lips were bright blue. A thin film of ice had formed around the torso, hiding the lower half of the body completely. The right arm, streaked with blood, hung limply over the edge of the tub, its fingers dipped in the congealed pool of blood on the floor. There was a razor blade on the edge of the tub. The other arm was visible only above the elbow, with the rest hidden beneath the ice. The knees also stuck up through the frozen surface. Alex’s long blonde hair was spread like a fan over the end of the tub but looked brittle and frozen in the cold.

Erica stood for a long time looking at her. She was shivering both from the cold and from the loneliness exhibited by the macabre tableau. Then she backed silently out of the room.

Afterwards, everything seemed to happen in a blur. She rang the doctor on duty on her mobile phone, and waited with Eilert until the doctor and the ambulance arrived. She recognized the signs of shock from when she got the news about her parents, and she poured herself a large shot of cognac as soon as she got home. Perhaps not what the doctor would order, but it made her hands stop shaking.

The sight of Alex had taken her back to her childhood. It was more than twenty-five years ago that they had been best friends, but even though many people had come and gone in her life since then, Alex was still close to her heart. They were just children back then. As adults they had been strangers to each other. And yet Erica had a hard time reconciling herself to the thought that Alex had taken her own life, which was the inescapable interpretation of what she had seen. The Alexandra she had known was one of the most alive and confident people she could imagine. An attractive, self-assured woman with a radiance that made people turn around to look at her. According to what Erica had heard through the grapevine, life had been kind to Alex, just as Erica had always thought it would be. She ran an art gallery in Göteborg, she was married to a man who was both successful and nice, and she lived in a house as big as a manor on the island of Särö. But something had obviously gone wrong.

Erica felt that she needed to divert her attention, so she punched in her sister’s phone number.

‘Were you asleep?’

‘Are you kidding? Adrian woke me up at three in the morning, and by the time he finally fell asleep at six, Emma was awake and wanted to play.’

‘Couldn’t Lucas get up for once?’

Icy silence on the other end of the line, and Erica bit her tongue.

‘He has an important meeting today, so he needed his sleep. Besides, there’s a lot of turmoil at his job right now. The company is in a critical strategic stage.’

Anna’s voice was getting louder, and Erica could hear an undertone of hysteria. Lucas always had a ready excuse, and Anna was probably quoting him directly. If it wasn’t an important meeting, then he was stressed out by all the weighty decisions he had to make, or his nerves were shot because of the pressure associated with being, in his own words, such a successful businessman. So all responsibility for the children fell to Anna. With a lively three-year-old and a baby of four months, Anna had looked ten years older than her thirty years when the sisters saw each other at their parents’ funeral.

‘Honey, don’t touch that,’ Anna shouted in English.

‘Seriously, don’t you think it’s about time you started speaking Swedish with Emma?’

‘Lucas thinks we should speak English at home. He says that we’re going to move back to London anyway before she starts school.’

Erica was so tired of hearing the words ‘Lucas thinks, Lucas says, Lucas feels that …’ In her eyes her brother-in-law was a shining example of a first-class shithead.

Anna had met him when she was working as an au pair in London, and she was instantly enchanted by the onslaught of attention from the successful stockbroker Lucas Maxwell, ten years her senior. She gave up all her plans of starting at university, and instead devoted her life to being the perfect, ideal wife. The only problem was that Lucas was a man who was never satisfied, and Anna, who had always done exactly as she pleased ever since she was a child, had totally eradicated her own personality after marrying Lucas. Until the children arrived, Erica had still hoped that her sister would come to her senses, leave Lucas, and start living her own life. But when first Emma and then Adrian were born, she had to admit that her brother-in-law was unfortunately here to stay.

‘I suggest that we drop the subject of Lucas and his opinions on child-rearing. What have auntie’s little darlings been up to since last time?’

‘Well, just the usual, you know … Emma threw a tantrum yesterday and managed to cut up a small fortune in baby clothes before I caught her, and Adrian has either been throwing up or screaming non-stop for three days.’

‘It sounds as though you need a change of scene. Can’t you bring the kids with you and come up here for a week? I could really use your help going through a bunch of stuff. And soon we’ll need to tackle all the paperwork too.’

‘Er, well … We were planning to talk to you about that.’

As usual when she had to deal with something unpleasant, Anna’s voice began to quaver noticeably. Erica was instantly on guard. That ‘we’ sounded ominous. As soon as Lucas had a finger in the pie, it usually meant that there was something that would benefit him to the detriment of all others involved.

Erica waited for Anna to go on.

‘Lucas and I have been thinking about moving back to London as soon as he gets the Swedish subsidiary on its feet. We weren’t really planning to bother with maintaining a house here. It’s no fun for you, either, having the hassle of a big country house. I mean, without a family and all …’

The silence was palpable.

‘What are you trying to say?’

Erica twirled a lock of her curly hair around her index finger, a habit she’d had since childhood and reverted to whenever she was nervous.

‘Well … Lucas thinks we ought to sell the house. It would be hard for us to hold on to it and keep it up. Besides, we want to buy a house in Kensington when we move back, and even though Lucas makes plenty of money, the cash from the sale would make a big difference. I mean, a house on the west coast in that area would go for several million kronor. The Germans are wild about ocean views and sea air.’

Anna kept pressing her argument, but Erica felt she’d heard enough and quietly hung up the phone in the middle of a sentence. Anna had certainly managed to divert her attention, as usual.

She had always been more of a mother than a big sister to Anna. Ever since they were kids she had protected and watched over her. Anna had been a real child of nature, a whirlwind who followed her own impulses without considering the results. More times than she could count, Erica had been forced to rescue Anna from sticky situations. Lucas had knocked the spontaneity and joie de vivre right out of her. More than anything else, that was what Erica could never forgive.

By morning, the events of the preceding day seemed like a bad dream. Erica had slept a deep and dreamless sleep, but still felt as though she’d barely had a catnap. She was so tired that her whole body ached. Her stomach was rumbling loudly, but after a quick peek in the fridge she realized that a trip to Eva’s Mart would be necessary before she was going to get any food to eat.

The town was deserted, and at Ingrid Bergman Square there was no trace of the thriving commerce of the summer months. Visibility was good, without mist or haze, and Erica could see all the way to the outer point of the island of Valö, which was silhouetted against the horizon. Together with Kråkholmen it bordered a narrow passage to the outer archipelago.

She met no one until she had walked halfway up Galärbacken. It was an encounter she would have preferred to avoid, and she instinctively looked for a possible escape route.

‘Good morning.’ Elna Persson’s voice chirped with unabashed sprightliness. ‘Well, if it isn’t our little authoress out walking in the morning sun.’

Erica cringed inside.

‘Yes, I was just on my way down to Eva’s to do a little shopping.’

‘You poor dear, you must be completely distraught after such a horrible experience.’

Elna’s double chins quivered with excitement, and Erica thought she looked like a fat little sparrow. Her woollen coat was shades of green and covered her body from her shoulders to her feet, giving the impression of one big shapeless mass. Her hands had a firm grip on her handbag. A disproportionately small hat was balanced on her head. The material looked like felt, and it too was an indeterminate moss-green colour. Her eyes were small and deeply set in a protective layer of fat. Right now they were fixed on Erica. Clearly she was expected to respond.

‘Yes, well, it wasn’t very pleasant.’

Elna nodded sympathetically. ‘Yes, I happened to run into Mrs Rosengren and she told me that she drove past and saw you and an ambulance outside the Carlgrens’ house, and we knew at once that something horrid must have happened. And later in the afternoon when I happened to ring Dr Jacobsson, I heard about the tragic event. Yes, he told me in confidence, of course. Doctors take an oath of confidentiality, and that’s something one has to respect.’

She nodded knowingly to show how much she respected Dr Jacobsson’s oath of confidentiality.

‘So young and all. Naturally one has to wonder what could be the reason. Personally I always thought she seemed rather overwrought. I’ve known her mother Birgit for years, and she’s a woman who has always been a bundle of nerves, and everyone knows that’s hereditary. She turned all stuck-up, too, Birgit I mean, when Karl-Erik got that big management job in Göteborg. Then Fjällbacka wasn’t good enough for her anymore. No, it was the big city for her. But I tell you, money doesn’t make anyone happy. If that girl had been allowed to grow up here instead of pulling up roots and moving to the big city, things wouldn’t have ended this way. I think they even packed the poor girl off to some school in Switzerland, and you know how things go at places like that. Oh yes, that sort of thing can leave a mark on a person’s soul for the rest of her life. Before they moved away from here, she was the happiest and liveliest little girl one could imagine. Didn’t you two play together when you were young? Well, in my opinion …’

Elna continued her monologue, and Erica, who could see no end to her misery, feverishly began searching for a way to extricate herself from the conversation, which was beginning to take on a more and more unpleasant tone. When Elna paused to take a breath, Erica saw her chance.

‘It was terribly nice talking to you, but unfortunately I have to get going. There’s a lot to be done. I’m sure you’ll understand.’

She put on her most pathetic expression, hoping to entice Elna onto this sidetrack.

‘But of course, my dear. I wasn’t thinking. All this must have been so hard for you, coming so soon after your own family tragedy. You’ll have to forgive an old woman’s thoughtlessness.’

By this point Elna was almost moved to tears, so Erica merely nodded graciously and hurried to say good-bye. With a sigh of relief she continued walking to Eva’s Mart, hoping to avoid any more nosy ladies.

But luck was not with her. She was grilled mercilessly by most of the excited residents of Fjällbacka, and she didn’t dare breathe freely until her own house was within sight. But one comment she heard stayed with her. Alex’s parents had arrived in Fjällbacka late last night and were now staying with her aunt.

Erica set the bags of groceries on the kitchen table and began putting away the food. Despite all her good intentions, the bags were not as full of staples as she had planned before she walked into the shop. But if she couldn’t buy herself treats on a day as miserable as this, when could she? As if on signal, her stomach started growling. With a flourish, she plopped twelve Weight Watchers points onto a plate in the form of two cinnamon buns. She ate them with a cup of coffee.

It felt wonderful to sit and look at the familiar view outside her window, but she still hadn’t got used to the silence in the house. She had been at home alone before, of course, but it wasn’t the same thing. Back then there had been a presence, an awareness that somebody could walk through the door at any moment. Now it seemed as if the soul of the house had gone.

Pappa’s pipe lay by the window, waiting to be filled with tobacco. The smell still lingered in the kitchen, but Erica thought it was getting fainter each day.

She had always loved the smell of a pipe. When she was little she often sat on her father’s lap and closed her eyes as she leaned against his chest. The smoke from the pipe had settled in all his clothing, and the scent had meant security in the world of her childhood.

Erica’s relationship with her mother was infinitely more complicated. She couldn’t remember a single time when she was growing up that she’d ever received a sign of tenderness from her mother; not a hug, a caress, or a word of comfort. Elsy Falck was a hard and unforgiving woman who kept their home in impeccable order but who never allowed herself to be happy about anything in life. She was deeply religious, and like many in the coastal communities of Bohuslän, she had grown up in a town that was still marked by the teachings of Pastor Schartau. Even as a child she had been taught that life would be endless suffering; the reward would come in the next life. Erica had often wondered what her father, with his good nature and humorous disposition, had seen in Elsy, and on one occasion in her teens she had blurted out the question in a moment of fury. He didn’t get angry. He just sat down and put his arm round her shoulders. Then he told her not to judge her mother too harshly. Some people have a harder time showing their feelings than others, he explained as he stroked her cheeks, which were still flushed with rage. She refused to listen to him then, and she was still convinced that he was only trying to cover up what was so obvious to Erica: her mother had never loved her, and that was something she would have to carry with her for the rest of her life.

Erica decided on impulse to visit Alexandra’s parents. Losing a parent was hard, but it was still part of the natural order of things. Losing a child must be horrible. Besides, she and Alexandra had once been as close as only best friends can be. Of course, that was almost twenty-five years ago, but so many of her happiest childhood memories were intimately associated with Alex and her family.

The house looked deserted. Alexandra’s maternal aunt and uncle lived in Tallgatan, a street halfway between the centre of Fjällbacka and the Sälvik campground. All the houses were perched high up on a slope, and their lawns slanted steeply down towards the road on the side facing the water. The main door was in the back of the house, and Erica did not hesitate before ringing the doorbell. The sound reverberated and then died out. Not a peep was heard from inside, and she was just about to turn and leave when the door slowly opened.