Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "The Teacher at Donegal Bay"

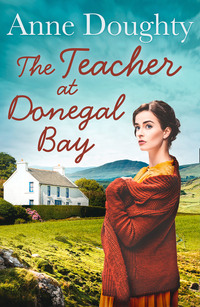

ANNE DOUGHTY is the author of A Few Late Roses, which was nominated for the longlist of the Irish Times Literature Prizes. Born in Armagh, she was educated at Armagh Girls’ High School and Queen’s University, Belfast. She has since lived in Belfast with her husband.

Also by Anne Doughty

The Girl from Galloway

The Belfast Girl on Galway Bay

Last Summer in Ireland

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published as A Few Late Roses in 1997

This edition published in Great Britain by HQ, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2019

Copyright © Anne Doughty 2019

Anne Doughty asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 9780008328818

Praise for Anne Doughty

‘This book was immensely readable, I just couldn’t put it down’

‘An adventure story which lifts the spirit’

‘I have read all of Anne’s books - I have thoroughly enjoyed each and every one of them’

‘Anne is a true wordsmith and manages to both excite the reader whilst transporting them to another time and another world entirely’

‘A true Irish classic’

‘Anne’s writing makes you care about each character, even the minor ones’

For Peter

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Also by Anne Doughty

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Dear Reader...

Keep Reading...

About the Publisher

Prologue

OCTOBER, 1995

My mother never talked about the past. What happened long ago was over and done with, water under the bridge, as far as she was concerned. She was wrong, of course. You can’t ignore the past. It always remains part of you. It shapes your present and your future and if you do try to ignore it, you could well end up as she did, bitter and disappointed and so out of love with herself and the whole world that she cast a dark shadow all around her.

That was how she nearly ruined my life.

Even in her dying my mother managed one final, bitter act. The morning after she died, my brother remembered the sealed envelope she had deposited with him some years earlier. He assumed it was a copy of her will, the provisions of which she’d quoted so many times we already knew them off by heart. It was indeed her will. But with it was a document he had not expected, a letter of instruction, handwritten in her own firm and well-formed copperplate.

‘Jenny dear, what in the name o’ goodness are we gonna do? Shure I had it all arranged with her own man and the undertaker down the road from the home. Hasn’t she upset the whole applecart?’

I knew he was badly shaken the moment I snatched up the phone in the bedroom where I was already packing. The steady, well-rounded tones that made him such a success with the patients in his Belfast consulting rooms had disappeared. I hadn’t heard Harvey sound like this since we were both children.

‘What d’ye think, Sis?’

I wasn’t surprised he’d had arrangements already made. For two years she’d been bedridden and almost immobile. She’d been at death’s door so many times that the kind-hearted staff at the nursing home became embarrassed about calling us yet once more to the bedside.

‘What exactly does it say, Harvey?’ I asked.

‘“I wish to be interred with my own family in the Hughes apportionment situated in Ballydrennan Churchyard, County Antrim, and not with my deceased husband George Erwin in the churchyard adjacent to Balmoral Presbyterian Church on the Lisburn Road.”’

He read it slowly and precisely, so that I could imagine her penning it, her lips tight, her shoulders squared. The more angry and bitter she was about something, the more formal the language she would use. In a really bad mood, she’d end up sounding like a legal document as she piled up words of sufficient weight and moment to serve her purposes. Consistent to the very end, I thought, as I listened.

‘And there’s a bit about the flowers,’ he added dismissively.

‘Oh, what does she say about flowers?’

‘She wants flowers. She says this idea of asking people to send money to some charity or other is a lot o’ nonsense and quite inappropriate.’

‘She would, wouldn’t she?’ I laughed wryly. ‘Shall we send a pillow of red roses, Harvey? Or one of those big square wreaths that say “Mum”, like the Kray brothers’, when they were let out of prison for their mother’s funeral?’

I heard him expostulate and made an effort to collect myself.

‘Sorry, Harvey, I’m not quite myself at the moment. I just can’t believe she’s gone. I’m all throughother, as she might say. In fact, when you rang I was standing here with one arm as long as the other when I’m supposed to be packing.’

He laughed shortly, but seemed comforted.

‘You’re the boss, Harvey. You backed me when Daddy died,’ I said gently. ‘If you want to go ahead with the Lisburn Road as planned, I’ll not object. We’re the only ones concerned, let’s face it.’

‘You’re shure, Jenny?’ he went on, a trace of relief already audible in his voice.

I stared round the disordered bedroom where two cases sat open and small piles of panties, Y-fronts, shirts and blouses were already lined up. I sat down abruptly, sweat breaking on my forehead.

‘No, no, I’m not sure, Harvey,’ I said weakly. ‘The minute I spoke, I knew it wouldn’t be right. Isn’t it silly? Can’t we even get free of her when she’s dead?’

In different circumstances, a countrywoman wanting to be buried with her family in the place where she was born could be a matter of sentiment. But there was no question of that with our mother. She’d never gone back to Ballydrennan after her father died, not even to visit her sister Mary who lived with her family only a few miles away. What was more, she’d never had a good word to say about the place. No, there was no question of sentiment. Only of spite.

Daddy had done all he could to give her what she wanted while he lived. When he died, he’d left her with a house, a car and a decent income. Now, one last time, she was rejecting him in the most public way possible. But something at the back of my mind told me we had to go through with it.

‘Harvey, I’m sorry, but I think we’ve got to do it. I can’t give you a single good reason why we should, but I have to be honest,’ I confessed. ‘I’m not being much help to you,’ I ended up lamely.

‘Yes, you are, Jenny. Being honest’s the only way. Took me a long time to see you’n Mavis were right about that. But you were. I’m much beholden to you, as they say,’ he added, with a slight, awkward laugh.

‘Maybe there has to be one last time, Harvey,’ I said quickly. ‘But it’ll make a lot of extra work for you.’

‘Don’t worry about that, Jenny,’ he replied easily. ‘Ring me when you’ve got your flight time and I’ll pick you up at Aldergrove.’

Two days later, in the crowded farm kitchen of our only remaining Antrim relatives, I took a large glass of whisky from the roughened hand of one of the McBride cousins and wondered how I could add a good measure of water without attracting attention. Before I could move, a huge figure embraced me.

‘Ach, my wee cousin.’

Jamsey McBride had always seemed large to me. When he’d carried me about on his shoulders as a little girl, he’d been like a great friendly bear, his remarkable physical strength offset by a surprising gentleness of manner.

‘Jamsey!’ I replied as the whisky sloshed in my glass.

‘Ach, shure Jenny, how are ye? Begod, shure I haven’t laid eyes on ye since your poor fader went. God rest his sowl, he was the best atall, the best atall. That mus’ be neer twenty year ago now. Dear aye, ye’ll see some changes in this place since last ye wor here. Aye, changes an’ heartbreak too.’

His eyes misted and I looked down into my glass to give him time to recover. Jamsey’s eldest son had been killed by paramilitaries early in the eighties and he still couldn’t speak of it without distress.

‘Now drink up, woman dear,’ he urged me after a moment. ‘Shure ye’ll be skinned down at the groun’. Yer fader usta say that wee hill the church stan’s on was the caulest place in the nine glens.’

So I drank my whisky as obediently as a child and listened to the ring of his Ulster Scots and tried to keep the tears from springing to my own eyes. No, it was not sorrow. Not tears for my mother or her passing, or even for Jamsey’s son, whom I had barely known, but tears of regret for the world I once knew, the people and places of my childhood.

Standing there in the large modern house that had replaced the low thatched cottage where my aunt and uncle began their married life, I mourned my links with the land and that part of my family who still lived closest to it. For these were people my mother had no time for, people whose hard-working lives she despised, whose successes and failures she treated with indifference or contempt.

A red-faced figure appeared at my elbow, the neck of a bottle of Bushmills aimed at my glass.

‘No, Patrick, no,’ I protested, laughing. ‘If I have any more, I won’t be able to stand up in church, never mind kneel down.’

He laughed aloud, clutched me by the arm and turned me to look across the crowded kitchen.

‘Jenny, is that yer girl over there forenenst that good-looking dark-haired lad?’

‘Yes, that’s Claire and her brother Stephen,’ I nodded. He winked at me, and pressed his way towards the next refillable glass.

Jamsey watched his brother work his way across the room and was silent for a moment.

‘Gawd Jenny, we’re all gettin’ aul,’ he began, sadly. ‘But that girl of yours is powerful like her granny. In luks, I mane,’ he added quickly.

‘I’m glad you added that, Jamsey,’ I said, laughing. ‘My mother could be a bit sharp.’

‘Ach, say no more, say no more,’ he muttered hastily. ‘Shure, don’t we know well enough she’d no time for the likes of us. But yer Da was a differen’ story. Ye’ve got very like him, Jenny. D’ye know that?’

‘It’s my grey hair, Jamsey. I see it’s in the fashion round here as well.’

‘Ach, away wi’ ye,’ he laughed, dropping a heavy hand on my shoulder. ‘Shure you’ve only a wee wisp or two at the front, an’ me has no hair atall, no moren a moily cow has horns. Tell me, d’ye like England, Jenny? Is it not too fast fer ye? Boys, I go over for Smithfeeld Show ivery year and the traffic gets worser. ’Twould run ye down and niver stop to cast ye aside.’

After the warmth and noise of the big kitchen, the chill of the October day took my breath away when we stepped outside. I shuddered so violently that Claire came and linked her arm through mine. ‘Get Daddy,’ I saw her mouth to Stephen, as the whole party set out on the short drive down one glen and into the next. A little later, the four of us walked up the rough path to the small grey church. Down by the gate, the cars were parked erratically on the grassy verge of the minor road, as if their occupants had gone fishing in a nearby lake or were playing football in someone’s field.

From behind the massed clouds that had threatened rain as we left McBride’s farm the sun suddenly appeared, casting one side of the deep glen into such dark shadow that the whitewashed houses gleamed like beacons. The church was in the light. Beyond its low hill and the curve of the Coast Road, full of the whiz of Saturday afternoon traffic, the white-capped rollers sparkled as they crashed on the rocky shore.

We followed the coffin into the empty, echoing church, its pale, peeling walls dappled with sunlight that fell through the high, undecorated windows. As we filled the first row of dark wooden pews, the undertaker’s men manoeuvred in the tiled space below the pulpit and placed the coffin on trestles so close to us I could have reached out and touched it.

We waited for the minister to appear and ascend to his vantage point. The silence deepened and the damp chill of the air and dead cold of the hard wooden bench began to eat into me. But, as the minister threw up his arms and made his opening flourish, I forgot all about being cold. At the first resounding reminder that we are all born to die, I heard, not the words, but the accent. Sharper and quite different from Jamsey’s slow drawl, his speech and his turn of phrase took me straight back to childhood, just like Jamsey’s had.

I did try to listen to the words from the pulpit but all I could hear were voices from the past, telling jokes and stories. Tears sprang to my eyes and I had to dab them surreptitiously while pretending to blow my nose.

‘She tried to take that away as well,’ I said to myself.

I stared at the wooden casket in disbelief. Yes, it was true. As far back as I could remember, she had tried to stop me visiting our relations in the glens. If it hadn’t been for my father I wouldn’t even have known they existed.

I shivered, tried to concentrate on the sermon, on the carved oak of the pulpit, on the scuffed wooden top of the untenanted harmonium. Anything to keep my mind away from what she had done. I wanted to weep as inconsolably as the child I had once been.

‘Brethren, let us pray.’

I breathed a sigh of relief as we shaded our eyes and bent our heads discreetly forward. It was so long since I’d been to a Presbyterian service I’d forgotten about not kneeling down. I hadn’t even warned Claire or Stephen, but they seemed to be taking it in their stride. I glanced sideways at Claire and found her grey eyes watching me from beneath her shaded brow. She smiled at me encouragingly.

I couldn’t think what on earth she and Stephen were making of the funeral service with its emphasis on repentance and the shortness of our mortal span. Their grandmother had never to my knowledge repented of anything and she had lived to the ripe old age of eighty-eight.

We stood up to be blessed and remained standing while the black-coated figures hoisted up their burden; one oak coffin with brass handles as specified by Edna Erwin, late of this parish, as per Harvey’s letter of instruction.

While we were in church the wind died away completely. When we emerged, a few handfuls of people marked out by our formal clothes as mourners, we stood blinking in the sunlight. McBride cousins in dark suits and well-polished shoes, elderly ladies wearing hats and hanging on the arms of sons or grandsons, a few people from Balmoral Presbyterian Church, discreet in grey or navy. Together, we found ourselves by the church door, bathed in the sudden warmth of the low sun.

Borne aloft on the stout shoulders of the undertaker’s men, the coffin glinted as we scrunched along the gravel on the south side of the church, tramped across the rich green sward beside the recent burials, and stepped cautiously onto the newly beaten path that meandered between the overgrown humps of unmarked graves and the tangles of long grass still laced with summer wildflowers.

Here, in the oldest part of the churchyard, in a burying place far older than the church that now stood empty behind us, we waited till the last able-bodied person had made the journey to the graveside. Beside my own small family stood Harvey and Mavis, their son Peter, and Susie their younger daughter. Beyond, the dark figures of Jamsey and Patrick McBride with their wives, Loreto and Norah. A dozen people altogether. Most of whom she disapproved of one way or another.

Words were spoken and the first shower of earth from the chalky mound piled up beyond the damp trench spattered on the shiny surface of the oak casket. Suddenly, the air was full of a rich, autumny perfume. The sun’s warmth playing on the mass of waiting flowers had drawn out their sweet, spicy smells.

Standing there by the open grave, I felt a surge of pure joy. Joy in the brilliance of the sky and the sparkle of the sea, joy in my own reconnection with this place I had once known so well, and joy in the three people dearest in all the world to me, who stood so close by my side, so ready to comfort me as I so often comforted them.

It was a moment of totally unexpected wellbeing I shall never forget. As I listened to the fall of earth and pebbles and the familiar words of the committal, I could think only of the joys of my own life, the happiness of my home and family, the success of my work, the pleasure of friends, the problems and difficulties survived and overcome. As the damp earth obliterated the polished plaque on which my mother’s mortal span had been clearly visible, Edna Erwin, 1902-1990, I remembered yet again that this moment of joy might never have been if she’d had her way. However mixed and variable its character, my happiness these many years could just as easily have been buried in my past.

I stood in the sunshine, the rhythmic crash of the breakers and the peremptory call of the jackdaws etching themselves into my memory. It was twenty-two years, almost to the day, since the weekend that had changed the course of my life. It was time I went back and found out what really happened that weekend.

Chapter 1

BELFAST 1968

The door clicked shut. As the footsteps of my sixth-formers echoed on the wooden stairs, I put my face in my hands and breathed a sigh of relief. My head ached with the rhythmic throbbing that gets worse if a fly buzzes within earshot or a door bangs two floors away. There was aspirin in my handbag, but the nearest glass of water was on the ground floor and the thought of weaving my way down through the noisy confusion of landings and overspilling cloakrooms was more than I could bear.

I made a note in the margin of my Shakespeare and closed it wearily. I enjoy the history plays and try to dramatise them when I teach, but today my effort with Richard III and his machinations seemed flat and stale. Hardly surprising after a short night, an early start, and an unexpected summons to the Headmistress’s study in the lunch hour. After that, I could hardly expect to be my shining best, but I still felt disappointed.

I stretched my aching shoulders, rubbed ineffectually at the pain in my neck, and reminded myself that it was Friday. The noise from below was always worse on a Friday afternoon, but it came to an end much more quickly than other days. Soon, silence would flow back into the empty classrooms and I might be able to think again.

I looked around the room where I taught most of my A-level classes. Once a servant’s bedroom in this tall, Edwardian house, the confined space was now the last resting place of objects with no immediate purpose. Ancient textbooks, music for long-forgotten concerts, programmes for school plays and old examination papers were piled into the tall bookcases which stood against two of the walls. Another tide of objects had drifted into the dim corners furthest from the single dusty window: a globe with the British Empire in fading red blotches; a bulging leather suitcase labelled ‘Drama’; a box inscribed ‘Bird’s Eggs’; a broken easel; and a firescreen embroidered with a faded peacock.

There were photographs too, framed and unframed, spotted with age. Serried ranks of girls in severe pinafores, accompanied by formidable ladies with bosoms and hats, the mothers and grandmothers of the girls who now poured out of the adjoining houses which made up Queen’s Crescent Grammar School.

I wondered yet again why the things of the past are so often neglected, left to lie around unsorted, neither cleared away nor brought properly into the present, to be valued for use or beauty. I thought of my own small collection of old photographs, a mere handful that had somehow survived my mother’s rigorous throwing out: Granny and Grandad Hughes standing in front of the forge with my mother; my father in overalls, with his first car, parked outside the garage where he worked in Ballymena; and a studio portrait of my grandmother, Ellen Erwin, clear-eyed, long-haired and wistful, when she was only sixteen. That picture was one of my most precious possessions.

My husband, Colin, says I’m sentimental and he finds it very endearing. But I don’t think it’s like that at all. I think your life starts long before you’re born, with people you may never even know, people who shape and mould the world into which you come. If I were ever to write the story of my life, it would have to begin well before the date on my birth certificate and I couldn’t do it without the fragments that most people neglect or throw away, like these faded prints at Queen’s Crescent.

The throb in my head had eased slightly as the noise level dropped from the fierce crescendo around four o’clock to the random outbursts of five minutes past. Another few minutes and I really would be able to get to my feet and collect my scattered wits.

I stared out through the dusty window at the house opposite. In the room the mirror image of mine, there were filing cabinets; a young man in shirt sleeves bent over a drawingboard under bright fluorescent tubes. On the floors below, each window framed a picture. Girls in smart dresses sat on designer furniture, in newly decorated offices with shiny green pot plants. They answered telephones, made photocopies and poured out cups of Cona coffee, disappearing with them to the front of the house, to their bosses who occupied the still elegant rooms that looked out upon the wide pavements of the next salubrious crescent.

Colin would be having tea by now. Outside the large conference room in the thickly carpeted lobby, waitresses in crisp dresses would pour from silver teapots and hand tiny sandwiches to men who dropped their briefcases on their chairs and greeted each other with warm handshakes. Beyond the air-conditioned rooms of the beflagged hotel, I saw the busy London streets, the traffic whirling ceaselessly round islands of green in squares where you could still hear a blackbird sing.

Daddy would probably be in the garden. He might be talking to the tame blackbird that follows his slight figure up and down the rosebeds as he weeds, working steadily and methodically, as if he could continue all day and never get tired. ‘Pace yourself, Jenny,’ he’d say, as he taught me how to loosen the weeds and open the soil. ‘No use going at it like a bull at a gate. Give it the time it needs. Don’t rush it.’

He was right, of course. He usually was. A mere two hours since I’d been summoned to Miss Braidwood’s study and here I was, so agitated by what she’d said that I’d gone and given myself a headache when I had the whole weekend to work things out.

I glanced at my watch and thought of all the things I ought to be doing. But I still made no move. My mind kept going back to that lunchtime meeting. I looked round the room again. This was where I worked, where I spent my solitary lunch hours, a place where I was free to think, or to sit and dream. It wasn’t a question of whether I liked it or not, it was what it meant to me that mattered.

Up here, I could even see the hard edge of the Antrim Hills lifting themselves above the city, indifferent to the housing estates which spattered their flanks and the roads which snaked and looped up and out of the broad lowland at the head of the lough.

At the thought of the hills, invisible from where I sat, I was overcome with longing. Oh, to be driving out of the city. I closed my eyes and saw the road stretch out before me, winding between hedgerows thick with summer green, the buttercups gleaming in the strong light. Daddy and I, setting off to see some elderly relative in her small cottage by the sea or tucked away in one of the nine Glens of Antrim, whose names I could recite like a poem. The fresh wind from the sea tempering the summer heat, the sky a dazzle of blue, we move through meadow and moorland towards the rough slopes of a great granite outcrop.

‘Well, here we are, Jenny. Slemish. Keeping sheep here must’ve been fairly draughty. Pretty grim in winter even for a saint. Can we climb it, d’ye think?’

‘Oh yes, please. We’ll be able to see far more from the top.’

Bracken catching at my ankles, the mournful bleat of sheep, the sun hot on my shoulders as we circle upwards between huge boulders. A hawthorn tree still in bloom, though it is nearly midsummer, shelters a spring bubbling up among the rocks. We stop and drink from cupped hands. There isn’t another soul on the mountain and no other car parked beside us on the rough edge of the lane below. As we climb, the whole province of Ulster unrolls before us, until at last we stand in the wind, between the coast of Scotland on one far horizon and the mountains of Donegal, blue and misted, away to the west.

‘Isn’t that the Mull of Kintyre, Daddy?’

‘Yes, dear. That’s the Mull of Kintyre,’ he replied, as if his thoughts were as far away as the bright outline beyond the shimmering sea.

Reluctantly, I got to my feet. Daydreaming, my mother would call it, but the tone of her voice would make the weakness into a crime should she catch me at it.

‘Jennifer, you have got to get to that bookshop,’ I said to myself severely. There was shopping as well and whatever else happened I had to be at Rathmore Drive by 5.30 p.m.

The staffroom door was ajar. Gratefully, I pushed it wide open with my elbow, dropped the exercise books on the nearest surface and breathed a sigh of relief. No one sat on the benches beside the long plastic-covered tables. There was no one by the handsome marble fireplace, peering at the timetables and duty lists pinned to the tattered green noticeboard perched on the mantelpiece. Best of all, no one crouched by the corner cupboard, where a single broad shelf was labelled ‘J. McKinstry – English’.

I winced as the light from naked fluorescent tubes flooded the room. Mercilessly, it exposed the peeling paintwork of cupboards and skirtings, layers of dust on leafy plaster interlacings. It also revealed a folded sheet of paper bearing a badly smudged map of the world in an empty corner of the message board. Across the width of what survived of Asia, my name was neatly printed. Hastily, I read the note:

I should like to have a word with you about Millicent Blackwood. Could you please come to me in the Library on Monday at 1 p.m. before I raise the matter with Miss Braidwood. E. Fletcher.

My heart sank as I picked up the tone. Millie, poor dear, was yet another of the things I had to think about over the weekend. Oh well. I tucked the note in my handbag, switched off the lights and left the building to the mercy of the cleaners.

‘Bread,’ I said to myself. The pavements were damp and slippery with fallen leaves, the lights streamed out from shops and glistened on their trampled shapes. I looked up at the sky, heavy and overcast. There was no sign at all of the hills. I’d have given so much for a bright autumny afternoon. Then the hills would seem near enough to touch, just down the next road, or beyond the solid redbrick mill, or behind the tall mass of the tobacco factory.

But today they lay hidden under the pall of cloud, leaving me only the less lovely face of the city that had been my home for most of my childhood and all but two of my adult years. Thirty years ago Louis MacNeice called it ‘A city built upon mud; a culture built upon profit’, and it hadn’t changed much in all the years since.

I made my way to the little bakery where I buy my weekly supplies, a pleasant, homely place where bread and cakes still come warm to the counter from behind a curtain of coloured plastic ribbons. In my second year at Queen’s, Colin and I used to visit it regularly, to buy rolls for a picnic lunch, or a cake for someone’s birthday. It hadn’t changed at all. Even Mrs Green was still there, plumper and greyer and more voluble than ever.

She prides herself she’s known Colin and me since before we were even engaged. She’s followed our life as devotedly as she watches Coronation Street. Graduation and wedding, first jobs in Birmingham and visits home. I remember her asking if she might see the wedding album and how she marvelled at the enormous and ornate volume Colin’s mother had insisted upon. These days, she asked about the house or the car, the decor of the living room or the health of our parents, Colin’s prospects or our plans for the future.

I paused, my fingers already tight on the handle of the door. I turned my back on it and walked quickly away.