Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Superior"

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2019

Copyright © Angela Saini 2019

The right of Angela Saini to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988

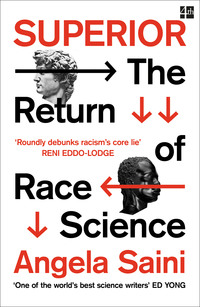

Cover: Michelangelo (Buonarroti, Michelangelo 1475–1564) David – detail (head in profile). Florence, Accademia. © 2019. Photo SCALA, Florence – courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali e del Turismo. Francis Harwood (1726/1727–1783) Bust of a Man. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008293864

Ebook Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9780008293840

Version: 2020-04-21

Praise for Superior:

‘This is an essential book on an urgent topic by one of our most authoritative science writers’

SATHNAM SANGHERA, author of The Boy with the Topknot

‘Whether you think of racist science as bad science, evil science, alt-right science, or pseudoscience, why would any contemporary scientist imagine that gross inequality is a fact of nature, rather than of political history? Angela Saini’s Superior connects the dots, laying bare the history, continuity, and connections of modern racist science, some more subtle than you might think. This is science journalism at its very best!’

JONATHAN MARKS, author of Tales of the Ex-Apes

‘Angela Saini’s investigative and narrative talents shine in Superior, her compelling look at racial biases in science past and present. The result is both a crystal-clear understanding of why race science is so flawed, and why science itself is so vulnerable to such deeply troubling fault lines in its approach to the world around us – and to ourselves’

DEBORAH BLUM, author of The Poison Squad

‘This deeply researched and unsettling book blends history, interviews, and the author’s personal experiences growing up as an Indian girl in a white working-class section of London … An important and timely reminder that race is “a social construct” with “no basis in biology”’

Kirkus (starred review)

‘Angela Saini’s Superior is nothing short of a remarkable, brilliant, and erudite exploration of what we believe about the racialized differences among our human bodies. Saini takes readers on a walking tour through science, art, history, geography, nostalgia and personal revelation in order to unpack many of the most urgent debates about human origins, and about the origin myths of racial hierarchies. This beautifully-written book will change the way you see the world’

JONATHAN M. METZL, author of Dying of Whiteness

‘Some writers have tackled the sordid history of race science previously, but none have gone so deep under the skin of the subject as Angela Saini in Superior. In her deceptively relaxed writing style, Saini patiently leads readers through the intellectual minefields of “scientific” racism. She plainly exposes the conscious and unconscious biases that have led even some of our most illustrious scientists astray’

MICHAEL BALTER, science journalist and author of The Goddess and the Bull

Dedication

For my parents, the only ancestors I need to know.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for Superior

Dedication

Prologue

1 Deep Time

2 It’s a Small World

3 Scientific Priestcraft

4 Inside the Fold

5 Race Realists

6 Human Biodiversity

7 Roots

8 Origin Stories

9 Caste

10 Black Pills

11 The Illusionists

Afterword

References

Index

Acknowledgements

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Prologue

‘In the British Museum is where you can see ’em

The bones of African human beings’

– Fun-Da-Mental, ‘English Breakfast’

I’M SURROUNDED BY DEAD PEOPLE, asking myself what I am.

Where I am is the British Museum. I’ve lived in London almost all my life and through the decades I’ve seen every gallery in the museum many times over. It was the place my husband took me on our first date, and years later, it was the first museum to which I brought my baby son. What draws me back here is the scale, the sheer quantity of artefacts, each seemingly older and more valuable than the last. I feel overwhelmed by it. But as I’ve learned, if you look carefully, there are secrets – secrets that undermine the grandeur, that offer a different narrative from the one the museum was built to tell.

When medical doctor, collector and slave owner Sir Hans Sloane bequeathed the British Museum’s founding collection upon his death in 1753, an institution was established that would come to document the entire span of human culture, in time and space. The British Empire was growing, and in the museum you can still see how these Empire-builders envisioned their position in history. Britain framed itself as the heir to the great civilisations of Egypt, Greece, the Middle East and Rome. The enormous colonnade at the entrance, completed in 1852, mimics the architecture of ancient Athens. The neo-classical style Londoners associate with this corner of the city owes itself to the fact that the British saw themselves as the cultural and intellectual successors of the Greeks and Romans.

Walk past the statues of Greek gods, their bodies considered the ideal of human physical perfection, and you’re witness to this narrative. Walk past the white marble sculptures removed from the Parthenon in Athens even as they crumbled, and you begin to see the museum as a testament to the struggle for domination, for possession of the deep roots of civilisation itself. In 1798, when Napoleon conquered Egypt and a French army engineer uncovered the Rosetta Stone, allowing historians to translate Egyptian hieroglyphs for the first time, this priceless object was claimed for France. A few years after it was found, the British took it as a trophy and brought it here to the museum. They vandalised it with the words, ‘Captured in Egypt by the British Army’, which you can still see carved into one side. As historian Holger Hoock writes, ‘the scale and quantity of the British Museum’s collections owe much to the power and reach of the British military and imperial state.’

The museum served one story. Great Britain, this small island nation, had the might to take treasures, eight million exquisite objects from every corner of the globe, and transport them here. The inhabitants of Rapa Nui (Easter Island, as European explorers called it) built the enormous bust of Hoa Hakananai’a to capture the spirit of one of their ancestors, and the Aztecs carved the precious turquoise double-headed serpent as an emblem of authority, but in the nineteenth century both these jewels found their way here and here they’ve remained. To add insult to injury, they’re just two of many, joining objects thousands of years older from Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley. No single item in the museum is more important than the museum itself. All these jewels brought together like this have an obvious tale to tell, one constructed to remind us of Britain’s place in the world. It’s a testament to the audacity of power.

And this is why I’m at the museum once again. When I set out to write this book, I wanted to understand the biological facts around race. What does modern scientific evidence really tell us about human variation, and what do our differences mean? I read the genetic and medical literature, I investigated the history of the scientific ideas, I interviewed some of the leading researchers in their fields. What became clear was that biology can’t answer this question, at least not fully. The key to understanding the meaning of race is understanding power. When you see how power has shaped the idea of race and continues to shape it, how it affects even the scientific facts, everything finally begins to make sense.

It was not long after the British Museum was founded that European scientists began to define what we now think of as race. In 1795, in the third edition of On the Natural Varieties of Mankind, German doctor Johann Friedrich Blumenbach described five human types: Caucasians, Mongolians, Ethiopians, Americans and Malays, elevating Caucasians – his own race – to the status of most beautiful of them all. Being precise, ‘Caucasian’ refers to people who live in the mountainous Caucasus region between the Black Sea to the west and the Caspian Sea to the east, but under Blumenbach’s sweeping definition it encompassed everyone from Europe to India and North Africa. It was hardly scientific, even by the standards of his time, but his vague human taxonomy would nevertheless have lasting consequences. Caucasian is the polite word we still use today to describe white people of European descent.

The moment we were sifted into biological groups, placed in our respective galleries, was the beginning of the madness. Race feels so real and tangible now. We imagine that we know what we are, having forgotten that racial classification was always quite arbitrary. Take the case of Mostafa Hefny, an Egyptian immigrant to the United States who considers himself very firmly and very obviously black. According to the rules laid out by the US government in its 1997 Office of Management and Budget standards on race and ethnicity, people who originate in Europe, the Middle East and North Africa are officially classified as white, in the same way that Blumenbach would have categorised Hefny as Caucasian. So in 1997, aged forty-six, Hefny filed a lawsuit against the United States government to change his official racial classification from white to black. He points to his skin, which is darker than that of some self-identified black Americans. He points to his hair, which is black and curlier than that of some black Americans. To an everyday observer, he’s a black man. Yet the authorities insist that he is white. His predicament still hasn’t been resolved.

Hefny isn’t alone. Much of the world’s population falls through some crack or another when it comes to defining race. What we are, this hard measure of identity, so deep that it’s woven into our skin and hair, a quality nobody can change, is harder to pin down than we think. My parents are from India, which means I’m variously described as Indian, Asian, or simply ‘brown’. But when I grew up in south-east London in the 1990s, those of us who weren’t white would often be categorised politically as black. The National Union of Journalists still considers me a ‘Black member’. By Blumenbach’s definition, being ancestrally north Indian makes me Caucasian. Like Mustafa Hefny then, I too am ‘black’, ‘white’ and other colours, depending on what you prefer.

We can draw lines across the world any way we choose, and in the history of race science, people have. What matters isn’t where the lines are drawn, but what they mean. The meaning belongs to its time. And in Blumenbach’s time, the power hierarchy had white people of European descent sitting at the top. They built their scientific story of the human species around this belief. They were the natural winners, they thought, the inevitable heirs of the great ancient civilisations nearby. They imagined that only Europe could have been the birthplace of modern science, that only the British could have built the railway network in India. Many still imagine that white Europeans have some innate edge, some superior set of genetic qualities that has propelled them to economic domination. They believe, as French President Nicolas Sarkozy said in 2007, that ‘the tragedy of Africa is that the African has not fully entered into history … there is neither room for human endeavour nor the idea of progress.’ The subtext is that history is over, the fittest have survived, and the victors have been decided.

But history is never over. There are objects in the British Museum that scream this truth silently, that betray the secret the museum tries to hide.

When you arrive for the first time it’s almost impossible to notice them because they’re so easily ignored by visitors in a rush to tick off every major treasure. You join the other fish in the shoal. But go upstairs to the Ancient Egypt galleries, to the plaster cast of a relief from the temple of Beit el-Wali in Lower Nubia, built by the pharaoh Ramesses II, who died in 1213 BCE. It’s high near the ceiling, spanning almost the entire room. See the pharaoh depicted as an impressive figure on a chariot, wearing a tall blue headdress and brandishing a bow and arrow, his skin painted burnt ochre. He’s ploughing into a legion of Nubians, dressed in leopard skins, some painted with black skin and some the same ochre as him. He sends their limbs into a tangle before they’re finally conquered. As the relief shows, the Egyptians at that time believed themselves to be a superior people with the most advanced culture, imposing order on chaos. The racial hierarchy, if that’s what you want to call it, looked this way in this time and place.

Then things changed. Downstairs on the ground floor is a granite sphinx from a century or two later, a reminder of the time when the Kushites, inhabitants of an ancient Nubian kingdom located in present-day Sudan, invaded Egypt. There was a new winner now, and the Ram Sphinx protecting King Taharqo – the black king of Egypt – illustrates how this conquering force took Egyptian culture and appropriated it. The Kushites built their own pyramids, the same way that the British would later replicate classical Greek architecture.

Through objects like this you can understand how power balances shift throughout history. They reveal a less simple version of the past, of who we are. And it’s one that demands humility, warning us that power is fleeting. More importantly, they show that knowledge is not just an honest account of what we know, but has to be seen as something manipulated by those who happen to hold power when it is written.

The Ancient Egypt galleries of the British Museum are always the most crowded. As we walk past the ancient mummies in their glittering cases we don’t always recognise that this is also a mausoleum. We’re surrounded by the skeletons of real people who lived in a civilisation no less remarkable than the ones that followed or that went before. Every society that happens to be dominant comes to think of itself as being the best, deep down. The more powerful we become, the more our power begins to be framed as not only cultural but natural. We portray our enemies as ugly foreigners and our subordinates as inferior. We invent hierarchies, give meaning to our own categories. One day, a thousand years forward, in another museum, in another nation, these could be European bones encased in glass, what was once considered an advanced society replaced by a new one. A hundred years is nothing; everything can change within a millennium. No region or people has a claim on superiority.

Race is the counter-argument. Race is at its heart the belief that we are born different, deep inside our bodies, perhaps even in character and intellect, as well as in outward appearance. It’s the notion that groups of people have certain innate qualities that are not only visible at the surface of their skins, but are intrinsic to their physical and mental capacities, that perhaps even help define the passage of progress, the success and failure of the nations our ancestors came from.

Notions of superiority and inferiority impact us in deep ways. I was told of an elderly man in Bangalore, south India, who ate his chapatis with a knife and fork because this was how the British ate. When my great-grandfather fought in the First World War for the British Empire and when my grandfather fought in the Second World War, their contributions were forgotten, like those of countless other Indian soldiers. They were considered not strictly equal to their white British counterparts. This is how it was. Generations of people in the twentieth century lived under colonial rule, apartheid and segregation, suffered violent racism and discrimination, because this is how it was. When boys from my school threw rocks at my sister and me when we were little, telling us to go home, this is how it was. I knew even as I bled that this is how it was. This is how it still is for many.

Race, shaped by power, has acquired a power of its own. We have so absorbed our classifications – the trend begun by scientists like Blumenbach – that we happily classify ourselves. Many of those who visit the British Museum for the first time (I can tell you this from having spent hours watching them) come searching for their own place in these galleries. The Chinese tourists go straight to the Tang dynasty artefacts; the Greeks to the Parthenon marbles. The first time I came here, I made a beeline for the Indian galleries. My parents were born in India, as were their parents, and theirs before them, so this is where I imagined I would find the objects most relevant to my personal history. So many visitors have that same desire to know who their ancestors were, to know what their people achieved. We want to see ourselves in the past, forgetting that everything in the museum belongs to us all as human beings. We are each products of it all.

But, of course, that’s not the lesson we take, because that’s not what the museum was designed to tell us. Trapped inside glass cabinets, fixed to the floors, why are these objects in these rooms, and not where they were first made? Why do they live inside this museum in London, its neo-classical columns stretching into the wet, grey sky? Why are the bones of Africans here, and not where they were buried, in the magnificent tombs that were created for them, where they were supposed to live out eternity?

Because this is how power works. It takes, it claims and it keeps. It makes you believe that this is where they belong. It’s designed to put you in your place.

The global power balance, as it played out in the eighteenth century, meant that treasures from all over the world could and would only end up in a museum like this, because Britain was one of the strongest nations at the time. It and other European powers were the latest colonisers, the most recent winners. So they gave themselves the right to take things. They gave themselves the right to document history their way, to define the scientific facts about humankind. European thinkers told us that their cultures were better, that they were the proprietors of thought and reason, and they married this with the notion that they belonged to a superior race. These became our realities.

The truth is something else.

1

Deep Time

Are we one human species, or aren’t we?

FLANKING A ROAD dotted with the corpses of unlucky kangaroos, three hundred kilometres inland from the Western Australian city of Perth – and the other end of the world from where I call home – is what feels like a wilderness. Everything is alien to my eyes. Birds I’ve never seen before make sounds I’ve never heard. The dead branches of silvery trees, skeleton fingers, extend out of crumbly red soil. Gigantic rocks weathered over billions of years into soft pastel blobs resemble mossy spaceships. I imagine I’ve been transported to a galaxy beyond time, one in which humans have no place.

Except that inside a dark shelter beneath one undulating boulder are handprints.

Mulka’s Cave is one of lots of ancient rock art sites dotted across Australia, but unique in this particular region for being so densely packed with images. I have to crouch to enter, navigating the darkness. One hand is all I see at first, stencilled within a spray of red ochre illuminated on the granite by a diffuse shaft of light. My eyes adjust, more hands appear. Infant hands and adult hands, hands on top of hands, hands all over the ceiling, hundreds of them in reds, yellows, oranges and whites. Becoming clearer in the half-light, it’s as though they’re pushing through the walls, willing for a high-five. There are parallel lines, too, maybe the vague outline of a dingo.

The images are hard to date. Some may be thousands of years old, others very recent. What is known is that the creation of rock art on this continent goes back to what in cultural terms feels like the dawn of time. Following excavation at the Madjedbebe rock shelter in Arnhem Land in northern Australia in 2017, it was conservatively estimated that modern humans had been present here for around 60,000 years – far longer than members of our species have lived in Europe, and long enough for people here to have witnessed an ice age, as well as the extinction of the giant mammals. And they may have been making art at the outset. At the Madjedbebe site, I’m told by one archaeologist who worked there, researchers found ochre ‘crayons’ worked down to a nub. At Lake Mungo in New South Wales, a site 42,000 years old, there is evidence of ceremonial burial, bodies sprinkled with ochre pigment that must have been transported there over hundreds of kilometres.

‘Something like a handprint is likely to have many different meanings in different societies and even within a society,’ says Benjamin Smith, a British-born rock art expert based at the University of Western Australia. It may be to signify place, possibly to assert that someone was here. But meaning is not always simple. The more experts like him have tried to decipher ancient art, wherever it is in the world, the more they’ve found themselves only scratching at the surface of systems of thought so deep that Western philosophical traditions can’t contain them. In Australia, a rock isn’t just a rock. The relationship that indigenous communities have with the land, even with inanimate natural objects, is practically boundless, everyone and everything intertwined.

What looks to me to be an alien wilderness isn’t wild at all. It’s a home that is more lived in than any I can imagine. Countless generations have absorbed and built upon knowledge of food sources and navigation. They have shaped the landscape sustainably over millennia, built a spiritual relationship with it, with its unique flora and fauna. As I learn slowly, in Aboriginal Australian thinking, the individual seems to melt away in the world around them. Time, space and object take on different dimensions. And none except those who have grown up immersed in this culture and place can quite understand it. I know that I could spend the rest of my life trying to fathom this and get no further than I am now, standing lonely in this cave.

We can’t inhabit minds that aren’t our own.

I was a teenager before I discovered that my mother might not actually know her own birth date. We were celebrating her birthday on the same day in October we always did when she told us in passing that her sisters thought she had actually been born in the summer. Pinning down dates hadn’t been routine when she was growing up in India. It surprised me that she didn’t care, and my surprise made her laugh. What mattered to her instead was her intricate web of family relationships, her place in society, her fate as mapped in the stars. And so I began to understand that the things we value are only what we know. I compare every city I visit with London, where I was born, for example. It’s the centre of my universe.

For archaeologists interpreting the past, deciphering cultures that aren’t their own is the challenge. ‘Archaeologists have struggled for a long time to determine what it is, what is that unique trait, what makes us special,’ says Smith, who as well as working in Australia has spent sixteen years at sites in South Africa. It’s a job that has taken him to the cradles of humankind, rummaging through the remains of the beginning of our species. And this is a difficult business. It’s surprisingly tough to date exactly when Homo sapiens emerged. Fossils of people who shared our facial features have been found from 300,000 to 100,000 years ago. Evidence of art, or at least the use of ochre, is reliably available in Africa far further back than 100,000 years, before some of our ancestors began venturing out of the continent and slowly populating other parts of the world, including Australia. ‘It’s one of the things that sets us apart as a species, the ability to make complex art,’ he says.

But even if our ancestors were making art a hundred millennia ago, the world then was nothing like the world now. More than forty thousand years ago there weren’t just modern humans, Homo sapiens, roaming the planet, but also archaic humans, including Neanderthals (sometimes called cavemen because their bones have been found in caves), who lived in Europe and parts of western and central Asia. And there were Denisovans, we now know, whose remains have been found in limestone caves in Siberia, their territory possibly spanning south-east Asia and Papua New Guinea. There were also at various times in the past many other kinds of human, most of which haven’t yet been identified or named.

In the deep past we all shared the planet, even living alongside each other at certain times, in particular places. For some academics, this cosmopolitan moment in our ancient history lies at the heart of what it means to be modern. When we imagine these other humans, it’s often as knuckle-dragging thugs. We must have had qualities that they didn’t have, something that gave us an edge, the ability to survive and thrive as they went extinct. The word ‘Neanderthal’ has long been a term of abuse. Dictionaries define it both as an extinct species of human that lived in ice-age Europe, and an uncivilised, uncouth man of low intelligence. Neanderthals and Homo erectus made stone tools like our own species, Homo sapiens, Smith explains, but as far as convincing evidence goes, he believes none had the same capacity to think symbolically, to talk in past and future tenses, to produce art quite like our own. These are the things that made us modern, that set us apart.

What separated ‘us’ from ‘them’ goes to the core of who we are. But it’s not just a question for the past. Today, being human might seem so patently clear, so beyond need for clarification that it’s hard to believe that not all that long ago it wasn’t so. When archaeologists found fossils of other now-extinct human species in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they raised doubts about just how far all Homo sapiens living today really are the ‘same’. Even as recently as the 1960s it wasn’t controversial for a scientist to believe that modern humans may have evolved independently in different parts of the world from separate archaic forms. Indeed, some are still plagued by uncertainty over this question. Scientific debate around what makes a modern human a modern human is as contentious as it has ever been.

From our vantage point in the twenty-first century, this might sound absurd. The common, mainstream view is that we have shared origins, as described by the ‘Out of Africa’ hypothesis. Scientific data has confirmed in the last few decades that Homo sapiens evolved from a population of people in Africa before some of these people began migrating to the rest of the world around 100,000 years ago and adapting in small ways to their own particular environmental conditions. Within Africa, too, there was adaptation and change depending on where people lived. But overall, modern humans were then (and remain now) one species, Homo sapiens. We are special and we are united. It’s nothing less than a scientific creed.

But this isn’t a view shared universally within academia. It’s not even the mainstream belief in certain countries. There are scientists who believe that, rather than modern humans migrating out of Africa relatively recently in evolutionary time, populations on each continent actually emerged into modernity separately from ancestors who lived there as far back as millions of years ago. In other words, different groups of people became human as we know it at different times in different places. A few go so far as to wonder whether, if different populations evolved separately into modern humans, maybe this could explain what we think of today as racial difference. And if that’s the case, maybe the differences between ‘races’ run deeper than we realise.

*

In one early European account of indigenous Australians, the seventeenth-century English pirate and explorer William Dampier called them ‘the miserablest people in the world’.

Dampier and the British colonists who followed him to the continent dismissed their new neighbours as savages who had been trapped in cultural stasis since migrating or emerging there, however long ago that was. Cultural researchers Kay Anderson, based at Western Sydney University, and Colin Perrin, an independent scholar, document the initial reaction of Europeans in Australia as one of sheer puzzlement. ‘The non-cultivating Aborigine bewildered the early colonists,’ they write. They didn’t build houses, they didn’t have agriculture, they didn’t rear livestock. They couldn’t figure out why these people, if they were equally human, hadn’t ‘improved’ themselves by adopting these things. Why weren’t they more like Europeans?