Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

Buch lesen: "Richard and Judy Bookclub - 3 Bestsellers in 1: The American Boy, The Savage Garden, The Righteous Men"

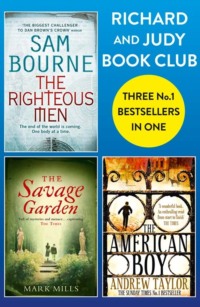

RICHARD AND JUDY BOOKCLUB

3 BESTSELLERS IN 1:

The American Boy The Savage Garden The Righteous Men

Andrew Taylor, Mark Mills and Sam Bourne

Contents

Cover

Title Page

The American Boy

The Savage Garden

The Righteous Men

Copyright

About the Publisher

THE AMERICAN BOY

ANDREW TAYLOR

Dedication

For Sarah and William. And, as always, for Caroline.

Epigraph

I would not, if I could, here or to-day, embody

a record of my later years of unspeakable

misery, and unpardonable crime.

From “William Wilson” by Edgar Allan Poe

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

The Wavenhoe Family, 1819

The Narrative of Thomas Shield, 1819–20

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Chapter 84

Appendix, 1862

A Historical Note on Edgar Allan Poe

Keep Reading

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by the Author

Copyright

The Wavenhoe Family, 1819:

N.B. The names underlined are of those members of the family who were alive in September 1819

THE NARRATIVE OF THOMAS SHIELD

8th September 1819 – 23rd May 1820

Chapter 1

We owe respect to the living, Voltaire tells us in his Première Lettre sur Oedipe, but to the dead we owe only truth. The truth is that there are days when the world changes, and a man does not notice because his mind is on his own affairs.

I first saw Sophia Frant shortly before midday on Wednesday the 8th of September, 1819. She was leaving the house in Stoke Newington, and for a moment she was framed in the doorway as though in a picture. Something in the shadows of the hall behind her had made her pause, a word spoken, perhaps, or an unexpected movement.

What struck me first were the eyes, which were large and blue. Then other details lodged in my memory like burrs on a coat. She was neither tall nor short, with well-shaped, regular features and a pale complexion. She wore an elaborate cottage bonnet, decorated with flowers. Her dress had a white skirt, puffed sleeves and a pale blue bodice, the latter matching the leather slipper peeping beneath the hem of her skirt. In her left hand she carried a pair of white gloves and a small reticule.

I heard the clatter of the footman leaping down from the box of the carriage, and the rattle as he let down the steps. A stout middle-aged man in black joined the lady on the doorstep and gave her his arm as they strolled towards the carriage. They did not look at me. On either side of the path from the house to the road were miniature shrubberies enclosed by railings. I felt faint, and I held on to one of the uprights of the railings at the front.

“Indeed, madam,” the man said, as though continuing a conversation begun in the house, “our situation is quite rural and the air is notably healthy.”

The lady glanced at me and smiled. This so surprised me that I failed to bow. The footman opened the door of the carriage. The stout man handed her in.

“Thank you, sir,” she murmured. “You have been very patient.”

He bowed over her hand. “Not at all, madam. Pray give my compliments to Mr Frant.”

I stood there like a booby. The footman closed the door, put up the steps and climbed up to his seat. The lacquered woodwork of the carriage was painted blue and the gilt wheels were so clean they hurt your eyes.

The coachman unwound the reins from the whipstock. He cracked his whip, and the pair of matching bays, as glossy as the coachman’s top hat, jingled down the road towards the High-street. The stout man held up his hand in not so much a wave as a blessing. When he turned back to the house, his gaze flicked towards me.

I let go of the railing and whipped off my hat. “Mr Bransby? That is, have I the honour –?”

“Yes, you have.” He stared at me with pale blue eyes partly masked by pink, puffy lids. “What do you want with me?”

“My name is Shield, sir. Thomas Shield. My aunt, Mrs Reynolds, wrote to you, and you were kind enough to say –”

“Yes, yes.” The Reverend Mr Bransby held out a finger for me to shake. He stared me over, running his eyes from head to toe. “You’re not at all like her.”

He led me up the path and through the open door into the panelled hall beyond. From somewhere in the building came the sound of chanting voices. He opened a door on the right and went into a room fitted out as a library, with a Turkey carpet and two windows overlooking the road. He sat down heavily in the chair behind the desk, stretched out his legs and pushed two stubby fingers into his right-hand waistcoat pocket.

“You look fagged.”

“I walked from London, sir. It was warm work.”

“Sit down.” He took out an ivory snuff-box, helped himself to a pinch and sneezed into a handkerchief spotted with brown stains. “So you want a position, hey?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And Mrs Reynolds tells me that there are at least two good reasons why you are entirely unsuitable for any post I might be able to offer you.”

“If you would permit me, I would endeavour to explain.”

“Some would say that facts explain themselves. You left your last position without a reference. And, more recently, if I understand your aunt aright, you have been the next best thing to a Bedlamite.”

“I cannot deny either charge, sir. But there were reasons for my behaviour, and there are reasons why those episodes happened and why they will not happen again.”

“You have two minutes in which to convince me.”

“Sir, my father was an apothecary in the town of Rosington. His practice prospered, and one of his patrons was a canon of the cathedral, who presented me to a vacancy at the grammar school. When I left there, I matriculated at Jesus College, Cambridge.”

“You held a scholarship there?”

“No, sir. My father assisted me. He knew I had no aptitude for the apothecary’s trade and he intended me eventually to take holy orders. Unfortunately, near the end of my first year, he died of a putrid fever, and his affairs were found to be much embarrassed, so I left the university without taking my degree.”

“What of your mother?”

“She had died when I was a lad. But the master of the grammar school, who had known me as a boy, gave me a job as an assistant usher, teaching the younger boys. All went well for a few years, but, alas, he died and his successor did not look so kindly on me.” I hesitated, for the master had a daughter named Fanny, the memory of whom still brought me pain. “We disagreed, sir – that was the long and the short of it. I said foolish things I instantly regretted.”

“As is usually the case,” Bransby said.

“It was then April 1815, and I fell in with a recruiting sergeant.”

He took another pinch of snuff. “Doubtless he made you so drunk that you practically snatched the King’s shilling from his hand and went off to fight the monster Bonaparte single-handed. Well, sir, you have given me ample proof that you are a foolish, headstrong young man who has a belligerent nature and cannot hold his liquor. And now shall we come to Bedlam?”

I squeezed the thick brim of my hat until it bent under the pressure. “Sir, I was never there in my life.”

He scowled. “Mrs Reynolds writes that you were placed under restraint, and lived for a while in the care of a doctor. Whether in Bedlam itself or not is immaterial. How came you to be in such a state?”

“Many men had the misfortune to be wounded in the late war. It so happened that I was wounded in my mind as well as in my body.”

“Wounded in the mind? You sound like a school miss with the vapours. Why not speak plainly? Your wits were disordered.”

“I was ill, sir. Like one with a fever. I acted imprudently.”

“Imprudent? Good God, is that what you call it? I understand you threw your Waterloo Medal at an officer of the Guards in Rotten-row.”

“I regret it excessively, sir.”

He sneezed, and his little eyes watered. “It is true that your aunt, Mrs Reynolds, was the best housekeeper my parents ever had. As a boy I never had any reason to doubt her veracity or indeed her kindness. But those two facts do not necessarily encourage me to allow a lunatic and a drunkard a position of authority over the boys entrusted to my care.”

“Sir, I am neither of those things.”

He glared at me. “A man, moreover, whose former employers will not speak for him.”

“But my aunt speaks for me. If you know her, sir, you will know she would not do that lightly.”

For a moment neither of us spoke. Through the open window came the clop of hooves from the road beyond. A fly swam noisily through the heavy air. I was slowly baking, basted in sweat in the oven of my own clothes. My black coat was too heavy for a day like this but it was the only one I had. I wore it buttoned to the throat to conceal the fact that I did not have a shirt beneath.

I stood up. “I must detain you no longer, sir.”

“Be so good as to sit down. I have not concluded this conversation.” Bransby picked up his eye glasses and twirled them between finger and thumb. “I am persuaded to give you a trial.” He spoke harshly, as if he had in mind a trial in a court of law. “I will provide you with your board and lodging for a quarter. I will also advance you a small sum of money so you may dress in a manner appropriate to a junior usher at this establishment. If your conduct is in any way unsatisfactory, you will leave at once. If all goes well, however, at the end of the three months, I may decide to renew the arrangement between us, perhaps on different terms. Do I make myself clear?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Ring the bell there. You will need refreshment before you return to London.”

I stood up again and tugged the rope on the left of the fireplace.

“Tell me,” he added, without any change of tone, “is Mrs Reynolds dying?”

I felt tears prick my eyelids. I said, “She does not confide in me, but she grows weaker daily.”

“I am sorry to hear it. She has a small annuity, I collect? You must not mind me if I am blunt. It is as well for us to be frank about such matters.”

There is a thin line between frankness and brutality. I never knew on which side of the line Bransby stood. I heard a tap on the door.

“Enter!” cried Mr Bransby.

I turned, expecting a servant in answer to the bell. Instead a small, neat boy slipped into the room.

“Ah, Allan. Good morning.”

“Good morning, sir.”

He and Bransby shook hands.

“Make your bow to Mr Shield, Allan,” Bransby told him. “You will be seeing more of him in the weeks to come.”

Allan glanced at me and obeyed. He was a well-made child with large, bright eyes and a high forehead. In his hand was a letter.

“Are Mr and Mrs Allan quite well?” Bransby inquired.

“Yes, sir. My father asked me to present his compliments, and to give you this.”

Bransby took the letter, glanced at the superscription and dropped it on the desk. “I trust you will apply yourself with extra force after this long holiday. Idleness does not become you.”

“No, sir.”

“Adde quod ingenuas didicisse fideliter artes.” He prodded the boy in the chest. “Continue and construe.”

“I regret, sir, I cannot.”

Bransby boxed the lad’s ears with casual efficiency. He turned to me. “Eh, Mr Shield? I need not ask you to construe, but perhaps you would be so good as to complete the sentence?”

“Emollit mores nec sinit esse feros. Add that to have studied the liberal arts with assiduity refines one’s manners and does not allow them to be coarse.”

“You see, Allan? Mr Shield was wont to mind his book. Epistulae Ex Ponto, book the second. He knows his Ovid and so shall you.”

When we were alone, Bransby wiped fragments of snuff from his nostrils with a large, stained handkerchief. “One must always show them who is master, Shield,” he said. “Remember that. Kindness is all very well but it don’t answer in the long run. Take young Edgar Allan, for example. The boy has parts, there is no denying it. But his parents indulge him. I shudder to think where such as he would be without due chastisement. Spare the rod, sir, and spoil the child.”

So it was that, in the space of a few minutes, I found a respectable position, gained a new roof over my head, and encountered for the first time both Mrs Frant and the boy Allan. Though I marked a slight but unfamiliar twang in his accent, I did not then realise that Allan was American.

Nor did I realise that Mrs Frant and Edgar Allan would lead me, step by step, towards the dark heart of a labyrinth, to a place of terrible secrets and the worst of crimes.

Chapter 2

Before I venture into the labyrinth, let me deal briefly with this matter of my lunacy.

I had not seen my aunt Reynolds since I was a boy at school, yet I asked them to send for her when they put me in gaol because I had no other person in the world who would acknowledge the ties of kinship.

She spoke up for me before the magistrates. One of them had been a soldier, and was inclined to mercy. Since I had indeed thrown the medal before a score of witnesses, and moreover shouted “You murdering bastard” as I did so, there was little doubt in any mind including my own that I was guilty. The Guards officer was a vengeful man, for although the medal had hardly hurt him, his horse had reared and thrown him before the ladies.

So it seemed there was only one road to mercy, and that was by declaring me insane. At the time I had little objection. The magistrates decided that I was the victim of periodic bouts of insanity, during one of which I had assaulted the officer on his black horse. It was a form of lunacy, they agreed, that should yield to treatment. This made it possible for me to be released into the care of my aunt.

She arranged for me to board with Dr Haines, whom she had consulted during my trial. Haines was a humane man who disliked chaining up his patients like dogs and who lived with his own family not far away from them. “I hold with Terence,” the doctor said to me. “Homo sum; humani nil a me alienum puto. To be sure, some of the poor fellows have unusual habits which are not always convenient in society, but they are made of the same clay as you or I.”

Most of his patients were madmen and half-wits, some violent, some foolish, all sad; demented, syphilitic, idiotic, prey to strange and fearful delusions, or sweeping from one extreme of their spirits to the other in the folie circulaire. But there were a few like myself, who lived apart from the others and were invited to take our meals with the doctor and his wife in the private part of the house.

“Give him time and quiet, moderate exercise and a good, wholesome diet,” Dr Haines told my aunt in my presence, “and your nephew will mend.”

At first I doubted him. My dreams were filled with the groans of the dying, with the fear of death, with my own unworthiness. Why should I live? What had I done to deserve it when so many better men were dead? At first, night after night, I woke drenched in sweat, with my pulses racing, and sensed the presence of my cries hanging in the air though their sound had gone. Others in that house cried in the night, so why should not I?

The doctor, however, said it would not do and gave me a dose of laudanum each evening, which calmed my disquiet or at least blunted its edge. Also he made me talk to him, of what I had done and seen. “Unwholesome memories,” he once told me, “should be treated like unwholesome food. It is better to purge them than to leave them within.” I was reluctant to believe him. I clung to my misery because it was all I had. I told him I could not remember; I feigned rage; I wept.

After a week or two, he cunningly worked on my feelings, suggesting that if I were to teach his son and daughters some Latin and a little Greek for half an hour each morning, he would be able to remit a modest proportion of the fees my aunt paid him for my upkeep. For the first week of this instruction, he sat in the parlour reading a book as I made the children con their grammars and chant their declensions. Then he took to leaving me alone with them, at first for a few minutes only, and then for longer.

“You have a gift for instructing the young,” the doctor said to me one evening.

“I show them no mercy. I make them work hard.”

“You make them wish to please you.”

It was not long after that he declared that he had done all he could for me. My aunt took me to her lodgings in a narrow little street running up to the Strand. Here I perched like an untidy cuckoo, mouth ever open, in her snug nest. I filled her parlour during the day, and slept there at night on a bed they made up on the sofa. During that summer, the reek from the river was well-nigh overwhelming.

I soon realised that my aunt was not well, that I had occasioned a severe increase in her expenditure since my foolish assault with the Waterloo Medal, and that my presence, though she strove to hide it, could not but be a burden to her. I also heard the groans she smothered in the dark hours of the morning, and I saw illness ravage her body like an invading army.

One day, as we drank tea after dinner, my aunt gave me back the Waterloo Medal.

It felt cold and heavy in the palm of my hand. I touched the ribbon with its broad, blood-red stripe between dark blue borders. I tilted my hand and let the medal slide on to the table by the tea caddy. I pushed it towards her.

“Where did it come from?”

“The magistrate gave it to me for you,” she said. “The one who was kind, who had served in the Peninsula. He said it was yours, that you had earned it.”

“I threw it away.”

She shook her head. “You threw it at Captain Stanhope.”

“Does not that amount to the same thing?”

“No.” She added, almost pleading, “You could be proud of it, Tom. You fought with honour for your King and your country.”

“There was no damned honour in it,” I muttered. But I took the medal to please her, and slipped it in my pocket. Then I said – and the one thing led to the other – “I must find employment. I cannot be a burden to you any longer.”

At that time jobs of any kind were not easy to find, particularly if one was a discharged lunatic who had left his last teaching post without a reference, who lacked qualifications or influence. But my aunt Reynolds had once kept house for Mr Bransby’s family, and he had a kindness for her. Upon threads of this nature, those chance connections of memory, habit and affection that bind us with fragile and invisible bonds, the happiness of many depends, even their lives.

All this explains why I was ready to take up my position as an under-usher at the Manor House School in the village of Stoke Newington on Monday the 13th of September. On the evening before I left my aunt’s house for the last time, I walked east into the City and on to London Bridge. I stopped there for a while and watched the grey, sluggish water moving between the piers and the craft plying up and down the river. Then, at last, I felt in my trouser pocket and took out the medal. I threw it into the water. I was on the upstream side of the bridge and the little disc twisted and twinkled as it fell, catching the evening sunshine. It slipped neatly into the river, like one going home. It might never have existed.

“Why did I not do that before?” I said aloud, and two shopgirls, passing arm in arm, laughed at me.

I laughed back, and they giggled, picked up their skirts and hastened away. They were pretty girls, too, and I felt desire stir within me. One of them was tall and dark, and she reminded me a little of Fanny, my first love. The girls skittered like leaves in the wind and I watched how their bodies swayed beneath thin dresses. As my aunt grows worse, I thought, I grow better, as though I feed upon her distress.

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.