Das Buch kann nicht als Datei heruntergeladen werden, kann aber in unserer App oder online auf der Website gelesen werden.

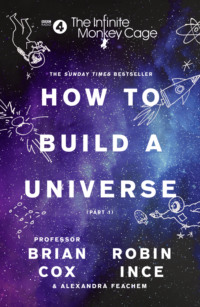

Buch lesen: "The Infinite Monkey Cage – How to Build a Universe"

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF WilliamCollinsBooks.com This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2017, 2018 Text © Brian Cox, Robin Ince and Alexandra Feachem 2017, 2018 Photographs © individual copyright holders Diagrams, design and layout © HarperCollins Publishers 2018 By arrangement with the BBC. The BBC logo is a trademark of the British Broadcasting Corporation and is used under licence. BBC logo © BBC 1996 The authors assert their moral right to be identified as the authors of this work. Cover photograph © Shutterstock Cover illustrations © Charlotte Ager, Holly O’Neil and Oliver Macdonald Oulds A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this eBook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Publishers. Source ISBN: 9780008276324 Ebook Edition © April 2018 ISBN: 9780008254964 Version: 2018-04-27

‘A joyous trip through our understanding of the universe’

Daily Express

Praise for BBC Radio 4’s The Infinite Monkey Cage:

‘A witty and irreverent look at the world according to science’

Independent

Praise for Professor Brian Cox:

‘Engaging, ambitious and creative’

Guardian

‘He bridges the gap between our childish sense of wonder and a rather more professional grasp of the scale of things’

Independent

‘Professor Cox shows us the cosmos as we have never seen it before – a place full of the most bizarre and powerful natural phenomena’

Sunday Express

Praise for Robin Ince:

‘Bursting with energy and ideas’

The Times

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

A Beginning

A Word from the Producer

Introductions & Infinity

Life, Death & Strawberries

Recipe to Build a Universe

Space Exploration

Evidence & Why Ghosts Don’t Exist

Apocalypse

Index

Acknowledgements

Episode List

Credits

About the Book

About the Authors

About the Publisher

A BEGINNING

A Very Special Foreword

by Eric Idle

Hello.

Sorry to come barging into this pseudo-scientific book, but obviously publishers are greedy bastards and will do anything they can to try to seduce the gullible public into buying enormous quantities of meretricious trash for the Christmas market, so I have been asked to lend my name to this blatant attempt to part you from your cash.

What is The Infinite Monkey Cage anyway – apart from being a terrific song written and sung by yours truly with every single instrument played by Jeff Lynne, and certainly something you should try to download for Christmas, but no, it’s the sodding BBC and it’s not available or they’d have to pay for something. That’s why you are stuck with this book.

I think you will find it very helpful. It’s useful for keeping a door propped open or to put on your Christmas table to stop the hot plates blistering the plastic tablecloth. But do watch out for the Christmas pud; the book itself is highly flammable, and if it catches, you might possibly set fire to an elderly aunt. On the other hand, if you are cold, simply stick it in the grate and it will make a lovely Christmas blaze.

As you know, scientists are the new chefs, so pity poor Ince, once a half-way decent comedian, now stuck alongside a glamour-boy professor, playing Robin to his Batman. Still, if it stops him having to play Colchester again I suppose the whole thing has been worth it.

One or two words about The Monkey Cage itself.

Is the Cage infinite?

Or are the Monkeys infinite?

Or perhaps they are both infinite?

In a multiverse would there be an Infinite

Donkey Cage?

I think we should be told.

Well, that’s about it.

I shall be spending my Christmas Day in the traditional way on a Thai massage table listening to Sounds of the Seventies. Sadly, we don’t get the Queen’s speech here in Bangkok, but there are one or two compensations. There is an inspirational message from José Mourinho, and a bottle of gluten-free almond wine for ancient tee-totalling ex-Pythons sent by John Cleese from his cellars, where he hangs upside down during the winter season.

To all of you, please enjoy your expanding Universe for another year. And do try to buy more Monty Python shit. We haven’t got long and we do need the cash.

Happy Christmas Greetings!

Eric Idle

The Old Jokes Home

Thailand

A WORD FROM THE PRODUCER

The Producer’s Tale

by Alexandra (Sasha) Feachem

Hello, I’m Sasha. I produce the radio show The Infinite Monkey Cage. I say produce, I use the term loosely. You’ll understand why in a moment. Brian thought it would be a good idea if I wrote something about what it is like to work with him and Robin. I’m not sure he had fully thought through that suggestion when he made it. I responded with hysterical enthusiasm. Brian looked scared. Perhaps punching the air and shouting ‘Yes! Finally the world will hear my story’ was a nanometre over the top.1 Despite this, and trying desperately to hide his alarmed expression behind a nervous smile, Brian realised that retracting the suggestion was clearly not an option… that the horse, or monkey keeper, had well and truly left the infinite zoo enclosure at something approaching the speed of light.

So here I am, with the producer’s tale; to tell you how The Infinite Monkey Cage evolved into existence and what it’s like to work with the infinite monkeys. And although the title of the show was in no way chosen to reflect the personalities of the people involved, or the way the radio show is put together, there is no doubt that we have all gloriously grown into the title. Thank goodness we didn’t call it Top Geek.

Back in 2008, CERN switched on the mother of all science experiments: the Large Hadron Collider. It is still the longest, fastest, most expensive science experiment ever undertaken. A particle smasher of biblical proportions, it recreates the moment just a billionth of a second after the Big Bang, and is the ultimate testament to what happens when human beings get together and ask why and what if? And when the Large Hadron Collider did switch on, Brian and I were sitting in the control room at CERN, alongside Andrew Marr, broadcasting to the nation, live on the Today programme. It was quite an odd experiment in itself, doing live coverage of a science experiment that is hidden underground and involves minuscule particles that I think even David Attenborough would fail to do justice to, especially on the radio. As Evan Davis commented from the safety of the Today studio back in London, ‘it’s a bit like Olympic taekwondo. It all sounds very interesting, but no one is quite sure what is actually going on.’

Luckily, the much predicted black hole that had gripped the popular press did not materialise and we all lived to tell the tale.2 And of course just a few years later, this extraordinary machine discovered the elusive Higgs particle, and with it gave us the origin of mass and opened a whole new chapter in our quest to understand the Universe we live in.

But perhaps the most extraordinary achievement of this jaw-dropping experiment was the interest it ignited in the general public; suddenly, incredibly, science was cool. Not just science, but particle physics. Some very well-known voices and faces emerged from the shadows and declared themselves fans of physics. Science had become, dare I say it, a little bit rock ‘n’ roll, and so the idea for The Infinite Monkey Cage was born.

Brian had told me some hilarious tales about celebrities he’d encountered on his travels, from dinners with Dan Aykroyd to finding himself in a hotel suite with Cameron Diaz and Queen Noor of Jordan… all fans of particle physics, not just Brian’s hair. One of Brian’s friends told us that we should try to get hold of Mick Jagger (he’s ‘way up on this shit’, apparently!). What could be more rock ‘n’ roll than that? (Mick – if you’re reading this, we’d still love to hear from you.) Robin, at this point, was regularly performing and curating his hugely popular stand-up shows, mixing scientists with comedians, and so this odd idea of a Radio 4 panel show featuring scientists and celebrities was born. Robin came up with the title and now, nearly 10 years later, it doesn’t seem like such an odd idea to have comedian Katy Brand on stage with Professor Carlos Frenk, one of the world’s most esteemed cosmologists. Or Ross Noble sitting alongside an expert in early human fossils. Or even a Python (Monty) and a geologist.

But I think the moment when I seriously began to believe in the possibility of parallel universes was the first time we took to the stage at Glastonbury, in 2011, to be greeted by the deafening cheers of more than 3000 people. These rock-festival goers, most of them still probably the worse for wear from the night before, had stampeded across fields of mud to cram into the cabaret tent at the most famous music festival in the country to see a comedian and a physicist take to the stage to talk about rationality, evidence and the wonders of science.

‘Who’s here for particle physics?’ shouted Robin. The 3000 people screamed back. ‘Quantum Chromodynamics?’ shouted Brian, to even more enthusiastic cheers. ‘It’s not very Radio 4 is it…?’ observed Brian. Not very Radio 4, and not, some might argue, very sciencey. But why shouldn’t it be?

One of the most frequent complaints we get to the radio programme (usually, I have to say, from people who have never listened), is that we are dumbing down science. Have you heard one of Brian and Robin’s introductions?! I’m sorry, but ‘yo mamma’s so massive she’s redshifted’ has got to be one of the most highbrow jokes ever heard on Radio 4. You need a PhD in astronomy to really keel over laughing at that one. The rest of us just sit and look a bit baffled, although we very much enjoy watching Brian giggling away and we feel happy that we know the joke might be funny once we’ve had a chance to go home and do some homework.3

To accuse the show of dumbing down science is to fundamentally misunderstand its purpose and the real reason why we all feel so passionately about its central message. Science is arguably the single biggest force in culture today. Cloning, genetic modification, nuclear power, the web, modern medicine – you name it, science is changing our world. Turn your back on science and you turn your back on the future and you fail to understand the present. To be truly engaged in society, everyone needs a basic grasp of what science is about and the way of thinking that leads to the advances that we all take for granted.

Science is vitally important, and therefore it must be part of popular culture. Why would anyone want to leave the foundation of our society to the boffins? They are just people, after all – they laugh, they cry, they watch Love Island like the rest of us.4 And comedians and entertainers read books, and newspapers, use hospitals and drive cars, and take an interest in the world around them, and in some cases had whole careers in quantum physics or cosmology before being lured away by the thrill of treading the boards (hello, Ben and Dara).

What I love most about working on the show is that in mixing these amazing people together, and putting a comedian and a physicist in charge, you never quite know what you are going to get. It’s chaotic and anarchic and a little bit terrifying if you are the producer, and possibly if you are the listener, too, but whatever the outcome, it is always interesting and surprising, and most of all we hope it makes people think. Brian and Robin really are the infinite monkeys, and although we may set out hoping to produce the works of Shakespeare, what emerges at the end, just like the theory we are named after, is a splendid testament to randomness. But despite the infinite chaos, and the anarchic bamboozlement, I hope we are never dull, and that we do the best job possible at fighting the corner for evidence, rational thinking and the glory and wonder of scientific endeavour and asking questions. After all, science allows you to write the secrets of the Universe on a blackboard, and what’s not to love about that?

1 Brian: A nanometre is 10-9 metres – that’s one-billionth of a metre. This sentence implies that Sasha went around 10 helium-atom-diameters over the line of acceptable excitement.

2 Brian: By ‘popular press’, Sasha means the Daily Mail, whose headline ‘Are we all going to die next Wednesday?’ should, if accuracy was the only goal, have led a one-word article: No.

3 Brian: This experience will be familiar to anyone who has been in the audience at one of Robin’s stand-up gigs.

4 Brian: I don’t even have to say it, do I?

AN INTRODUCTION

Welcome to

The Infinite Monkey Cage

Hello, I am Robin Ince.

And I am Brian Cox.

ROBIN: Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, our interest in space, technology and strange undersea creatures with terrifying tentacles or the ability to eat their own brains came from a mixture of Look and Learn magazine, The Six Million Dollar Man and Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World.

BRIAN: We were kids in the Indian summer of the space race, a little too young to remember the Moon landings, but the excitement of exploration still enthused us all. (I myself still own a Space 1999 outfit.) It was a time of Cold War danger and anxiety, but also of immense optimism and confidence in the promise of science and technology.

R: Sadly, Brian could never become an astronaut because he is too tall and I could never be one because I am too chatty… and short-sighted… and not very patient when it comes to misbehaving machines. So there is no way Apollo 13 would have returned to Earth if I’d been in there gallumphing about and kicking whatever bit of kit that refused to operate as I wanted it to. I am one of those unfortunate humans who believes that objects misbehave with the specific intention of ruining my day. I am likely to be found dead from a heart attack after a blazing row with an inanimate object.

B: Whilst Robin’s inability to operate machinery led him to become a comedian, via a degree in one or other of the humanities at some university or other, I became a particle physicist after a short detour via the music industry. Although even then I was primarily interested in programming the Roland MC-300 Micro Composer and only transferred my interest to sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll when my midi cable became frayed.

R: In the early 1980s, television was our teacher. Carl Sagan’s Cosmos is one of the main reasons why The Infinite Monkey Cage exists. Opening with the music of Vangelis, the composer who would also score Blade Runner – a film Brian loves as he now knows why he has the same dream about unicorns every night – Sagan’s ‘spaceship of the imagination’ travelled through nebulae and star systems. Music fades, camera pans across a cliff face and zooms into Carl Sagan, and we twelve-year-olds sat up, wide-eyed and eager, and heard the words:

‘The Cosmos is all that is, or ever was, or ever will be.’

And thus we were snared. Within minutes, we would know that we were all starstuff, that the stuff of us was the stuff of the stars. The atoms that were currently gathered to form the shape and minds of us had been forged in the furnace of stellar nurseries.

B: Carl Sagan was a pivotal figure for us because he made vivid the link between our science and our humanity. We are a part of the Cosmos, Sagan told us, and our fate is deeply connected with it. Science is devalued when separated from culture, and our experience of living is diluted when we become separated from science, because science is a necessary but not sufficient part of our exploration of what it means to be human. It is not possible to have a meaningful discussion about our place in the Cosmos without knowing its size and scale, without knowing that we are made of it and will return to it, without acknowledging the deep mysteries that await us as we push our understanding ever further back to the beginning of the Universe, 13.8 billion years ago.

Science is often celebrated because it is useful, and research is funded because it provides us with objects of perceived value. The true value of science is that it allows us to acquire reliable knowledge and teaches us humility. Your opinion is irrelevant in the face of nature; imagine the improvement in modern-day political discourse if that single sentence were seared into the forearm of every politician as a cow is branded with the mark of its owner?

Having said that, aircraft, mobile phones, medicine, electric light, refrigerators, vaccines, computers and radios are useful things, and Robin would struggle without the synthetic fibres that strengthen his book-filled rucksack.

We are a part of the Cosmos, Sagan told us, and our fate is deeply connected with it.

Raymond Baxter, the first presenter of Tomorrow’s World, seen here in 1970 with an innovative doll that can walk, talk and sing.

R: Tomorrow’s World told us of what was to come, and though often mocked for its adventurous predictions involving round cars on wheeled stilts, much of what was featured on the programme was accurate, intriguing and inspiring. Returning to it now, we are reminded of the speed of change. The unwieldy home computer of 1967 contains far less data-processing capacity than one of the twenty-first century’s fancier and, predominantly, pointless, wristwatches.

‘Imagine a world where every word ever written, every picture ever painted and every film ever shot could be viewed instantly in your home via an information superhighway, a high-capacity digital communication network… it sounds pretty grand, but in fact this is already happening on something called the internet’

Kate Bellingham told us in 1994.

1994!

Imagine a world without something called the internet. Imagine how hard it would be to shop, watch or destabilise democracy and seed disinformation.

William Wollard, former presenter on Tomorrow’s World, seen strolling up the roof of St Pancras Station in London in 1970, made possible through the cunning invention of Herbert Stokes’ ‘Roof Shoes’.

B: As children, the divide between science, pseudoscience and plain nonsense was not as marked in our minds as it is now, but perhaps paradoxically the lines were more clearly drawn in public discourse. In his book The Demon-Haunted World, published in 1995, Carl Sagan wrote: ‘I have a foreboding of an America in my children’s or grandchildren’s time – when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the key manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority; when, clutching our crystals and nervously consulting our horoscopes, our critical faculties in decline, unable to distinguish between what feels good and what’s true, we slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness.’

Sagan would have been horrified if his editor had said, ‘Carl, perhaps remove the grandchildren line…’

R: Having said that, to an inquisitive child in the 1970s, science was not only NASA and Einstein, but also Bigfoot and the Bermuda Triangle. When not leafing through David Attenborough’s Life on Earth, I might be reading The Unexplained magazine or Chariots of the Gods?, a book that didn’t ask if Neil Armstrong was an astronaut, but went further and asked if God was one.

The mind of a curious child was as open to questions of Bigfoot as it was of black holes; at that time, after all, the physical evidence for both was nil.

Made in 1967, the Patterson-Gimlin Bigfoot film was the Blair Witch Project of its time, the juddering graininess giving it a disconcerting authenticity. Why juddering graininess makes evidence more persuasive, I have no idea. It looks very like a biggish man in a gorilla costume wandering through a partially cleared woodland, but could it really be so simple?

According to the TV documentary, Chinese scientists had examined the footage and decided a man could not walk in such a lumbering manner. I myself have tried to walk in that way, both in and out of my gorilla costume, and I’ve found it surprisingly easy, but then, that might be evidence of a recessive Bigfoot gene revealing my family’s shameful Sasquatch dating past. Eventually, evidence-based investigation by author Greg Long revealed the truth of the Bigfoot film.

Retired labourer Bob Heironimus saw a documentary about the ‘Bigfoot hoax’ in 1998 and decided now was the time to own up that he was the human in the costume, bulked out by American-football shoulder pads and encased in a very smelly and claustrophobic mask that he had not enjoyed wearing at all. Those sceptical of scepticism may consider that this is a typical attempt by the National Parks Service to cover up their family of Bigfoots, but the next stage of investigation reveals the reason why you must avoid using anyone with a prosthetic eye when attempting to pull the wool over other people’s functioning eyes. The Bigfoot’s right eye reflects sunlight when looking at the camera because Bob had a glass eye. The sceptic sceptic may still declare, ‘but how do we know the Bigfoot has not developed glass-eye technology?’ and the mystery can continue if they’d like it to.

Still from the famous Patterson-Gimlin Bigfoot film made in North Carolina in October 1967.

Wilderness explorer C. Thomas Biscardi claimed to have captured Bigfoot on camera in northern California in 1981. He had been searching for the legendary ape-like creature for nearly a decade.

Another supposed ‘sighting’ of Bigfoot.

B: We recount this story for two reasons. One is to provide a glimpse into the confused and dusty book repository of Robin’s mind, where the windmills cannot turn freely because their mechanisms are clogged with VHS tape.

But it also illustrates what we hope The Infinite Monkey Cage is about; seeking evidence for working out why you believe what you believe and being open to changing your mind if the body of evidence leads to a different conclusion.

R: We currently live in a world where the quantity of information doubles with increasing speed. We can be overloaded by the extraneous. We can be misled by many groups and individuals who project the illusion of authority. For the open-minded and sceptical, the entire day can be lost just trying to work out if the front page of a newspaper is accurate. Dogma can be alluring when open-mindedness is so bewildering. It is troublesome to realise that nothing is 100 per cent right, but there are things which are the least-wrong version of events or ideas. Over the almost 100 episodes of The Infinite Monkey Cage we have recorded so far, we have tried as often as possible – whether dealing with race, climate change or cosmology – to demonstrate that the elasticity of an idea is determined by the evidence available. Where there is no evidence, you can stretch an idea as much as you want, but in this case the idea may be of little practical use and not one to inform your decisions.

Of the two of us, I am probably more sceptical when it comes to the views of scientists, though Brian may say that’s because I don’t understand the equations. We’ll explore some of our more incendiary stand-up rows later in the book.

Die kostenlose Leseprobe ist beendet.